Introduction - VideoLectures.NET

advertisement

Grammatical inference:

techniques and

algorithms

Colin de la Higuera

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

1

1

Acknowledgements

• Laurent Miclet, Tim Oates, Jose

Oncina,

Rafael

Carrasco,

Paco

Casacuberta,

Pedro

Cruz,

Rémi

Eyraud, Philippe Ezequel, Henning

Fernau,

Jean-Christophe

Janodet,

Thierry Murgue, Frédéric Tantini,

Franck Thollard, Enrique Vidal,...

• … and a lot of other people to whom

I am grateful

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

2

2

Outline

1

2

3

4

5

An introductory example

About grammatical inference

Some specificities of the task

Some techniques and algorithms

Open issues and questions

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

3

3

1 How do we learn languages?

A very simple example

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

4

4

The problem:

• You are in an unknown city

and have to eat.

• You therefore go to some

selected restaurants.

• Your goal is therefore to

build a model of the city (a

map).

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

5

5

The data

• Up Down Right Left Left

Restaurant

• Down Down Right Not a

restaurant

• Left Down Restaurant

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

6

6

Hopefully something like this:

u,r

N

u

d

R

d,l

u

N

r

R

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

d

7

7

N

d

u

N

d

u

R

R

d

N

u

N

R

u

R

u

d

d

r

R

d

N

u

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

8

8

Further arguments (1)

• How did we get hold of the

data?

– Random walks

– Following someone

• someone knowledgeable

• Someone trying to lose us

• Someone on a diet

– Exploring

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

9

9

Further arguments (2)

• Can

we

not

have

better

information (for example the

names of the restaurants)?

• But then we may only have the

information about the routes

to restaurants (not to the

“non restaurants”)…

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

10

10

Further arguments (3)

What if instead of getting

the information “Elimo” or

“restaurant”,

I

get

the

information “good meal” or

“7/10”?

Reinforcement learning: POMDP

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

11

11

Further arguments (4)

• Where is my algorithm to

learn these things?

• Perhaps

should

I

consider

several algorithms for the

different types of data?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

12

12

Further arguments (5)

• What can I

result?

• What can I

algorithm?

say

about

the

say

about

the

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

13

13

Further arguments (6)

• What if I want something

richer than an automaton?

– A context-free grammar

– A transducer

– A tree automaton…

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

14

14

Further arguments (7)

• Why do I want something as rich

as an automaton?

• What about

– A simple pattern?

– Some SVM obtained from features over

the strings?

– A neural network that would allow me

to know if some path will bring me or

not to a restaurant, with high

probability?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

15

15

Our goal/idea

• Old Greeks:

A whole is more than the sum of

all parts

• Gestalt theory

A whole is different than the

sum of all parts

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

16

16

Better said

• There are cases where the

data cannot be analyzed by

considering it in bits

• There

are

cases

where

intelligibility

of

the

pattern is important

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

17

17

What do people know about formal language

theory?

Nothing

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Lots

18

18

A small reminder on formal language theory

• Chomsky hierarchy

• + and – of grammars

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

19

19

A crash course in Formal language theory

• Symbols

• Strings

• Languages

• Chomsky hierarchy

• Stochastic languages

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

20

20

Symbols

are taken from some alphabet

Strings

are sequences of symbols from

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

21

21

Languages

are sets of strings over

Languages

are subsets of *

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

22

22

Special languages

• Are

recognised

by

finite

state automata

• Are generated by grammars

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

23

23

b

a

a

a

b

b

DFA: Deterministic Finite State Automaton

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

24

24

b

a

a

a

b

b

ababL

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

25

25

What is a context free grammar?

A

4-tuple

that:

(Σ,

S,

V,

P)

such

– Σ is the alphabet;

– V is a finite set of non

terminals;

– S is the start symbol;

– P V (VΣ)* is a finite set

of rules.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

26

26

Example of a grammar

The Dyck1 grammar

– (Σ,

–Σ =

–V =

–P =

S, V, P)

{a, b}

{S}

{S aSbS, S }

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

27

27

Derivations and derivation trees

S aSbS

aaSbSbS

aabSbS

aabbS

aabb

S

a

a

S

b

S

b

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

S

S

28

28

Chomsky Hierarchy

• Level

• Level

• Level

• Level

0:

1:

2:

3:

no restriction

context-sensitive

context-free

regular

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

29

29

Chomsky Hierarchy

• Level 0: Whatever Turing machines

can do

• Level 1:

– {anbncn: n }

– {anbmcndm : n,m }

– {uu: u*}

• Level 2: context-free

– {anbn: n }

– brackets

• Level 3: regular

– Regular expressions (GREP)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

30

30

The membership problem

• Level

• Level

• Level

• Level

0:

1:

2:

3:

undecidable

decidable

polynomial

linear

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

31

31

The equivalence problem

• Level 0: undecidable

• Level 1: undecidable

• Level 2: undecidable

• Level 3: Polynomial only when

the representation is DFA.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

32

32

1

2

a

b

1

2

1

2

1

3

1

4

a

a

1

2

b

3

4

b

2

3

PFA: Probabilistic Finite

(state) Automaton

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

33

33

0.1

b

a

0.9

0.7

a

0.35

0.7

b

0.3

a

0.3

b

0.65

DPFA: Deterministic Probabilistic

Finite (state) Automaton

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

34

34

What is nice with grammars?

• Compact representation

• Recursivity

• Says how a string belongs,

not just if it belongs

• Graphical

representations

(automata, parse trees)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

35

35

What is not so nice with grammars?

• Even the easiest class (level 3)

contains SAT, Boolean functions,

parity functions…

• Noise is very harmful:

– Think about putting edit noise to

language {w: |w|a=0[2]|w|b=0[2]}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

36

36

2 Specificities of grammatical

inference

Grammatical

inference

consists

(roughly) in finding the (a)

grammar or automaton that has

produced a given set of strings

(sequences,

trees,

terms,

graphs).

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

37

37

The field

Inductive Inference

Pattern Recognition

Machine Learning

Grammatical Inference

Computational linguistics

Computational biology

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Web technologies

38

38

The data

• Strings, trees, terms, graphs

• Structural objects

• Basically the same gap of

information as in programming

between tables/arrays and data

structures

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

39

39

Alternatives to grammatical inference

• 2 steps:

– Extract

features

from

the

strings

– Use a very good method over n.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

40

40

Examples of strings

A

string

in

Gaelic

translation to English:

and

its

• Tha

thu cho duaichnidh ri èarr

àirde de a’ coisich deas damh

•You are as ugly as the north end

of a southward traveling ox

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

41

41

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

42

42

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

43

43

>A BAC=41M14 LIBRARY=CITB_978_SKB

AAGCTTATTCAATAGTTTATTAAACAGCTTCTTAAATAGGATATAAGGCAGTGCCATGTA

GTGGATAAAAGTAATAATCATTATAATATTAAGAACTAATACATACTGAACACTTTCAAT

GGCACTTTACATGCACGGTCCCTTTAATCCTGAAAAAATGCTATTGCCATCTTTATTTCA

GAGACCAGGGTGCTAAGGCTTGAGAGTGAAGCCACTTTCCCCAAGCTCACACAGCAAAGA

CACGGGGACACCAGGACTCCATCTACTGCAGGTTGTCTGACTGGGAACCCCCATGCACCT

GGCAGGTGACAGAAATAGGAGGCATGTGCTGGGTTTGGAAGAGACACCTGGTGGGAGAGG

GCCCTGTGGAGCCAGATGGGGCTGAAAACAAATGTTGAATGCAAGAAAAGTCGAGTTCCA

GGGGCATTACATGCAGCAGGATATGCTTTTTAGAAAAAGTCCAAAAACACTAAACTTCAA

CAATATGTTCTTTTGGCTTGCATTTGTGTATAACCGTAATTAAAAAGCAAGGGGACAACA

CACAGTAGATTCAGGATAGGGGTCCCCTCTAGAAAGAAGGAGAAGGGGCAGGAGACAGGA

TGGGGAGGAGCACATAAGTAGATGTAAATTGCTGCTAATTTTTCTAGTCCTTGGTTTGAA

TGATAGGTTCATCAAGGGTCCATTACAAAAACATGTGTTAAGTTTTTTAAAAATATAATA

AAGGAGCCAGGTGTAGTTTGTCTTGAACCACAGTTATGAAAAAAATTCCAACTTTGTGCA

TCCAAGGACCAGATTTTTTTTAAAATAAAGGATAAAAGGAATAAGAAATGAACAGCCAAG

TATTCACTATCAAATTTGAGGAATAATAGCCTGGCCAACATGGTGAAACTCCATCTCTAC

TAAAAATACAAAAATTAGCCAGGTGTGGTGGCTCATGCCTGTAGTCCCAGCTACTTGCGA

GGCTGAGGCAGGCTGAGAATCTCTTGAACCCAGGAAGTAGAGGTTGCAGTAGGCCAAGAT

GGCGCCACTGCACTCCAGCCTGGGTGACAGAGCAAGACCCTATGTCCAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAGGAAAAGAAAAAGAAAGAAAACAGTGTATATATAGTATATAGCTGAAGCTCCC

TGTGTACCCATCCCCAATTCCATTTCCCTTTTTTGTCCCAGAGAACACCCCATTCCTGAC

TAGTGTTTTATGTTCCTTTGCTTCTCTTTTTAAAAACTTCAATGCACACATATGCATCCA

TGAACAACAGATAGTGGTTTTTGCATGACCTGAAACATTAATGAAATTGTATGATTCTAT

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

44

44

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

45

45

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

46

46

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

47

47

<book>

<part>

<chapter>

<sect1/>

<sect1>

<orderedlist numeration="arabic">

<listitem/>

<f:fragbody/>

</orderedlist>

</sect1>

</chapter>

</part>

</book>

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

48

48

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="carmen.xsl" type="text/xsl"?>

<?cocoon-process type="xslt"?>

<!DOCTYPE pagina [

<!ELEMENT pagina (titulus?, poema)>

<!ELEMENT titulus (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT auctor (praenomen, cognomen, nomen)>

<!ELEMENT praenomen (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT nomen (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT cognomen (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT poema (versus+)>

<!ELEMENT versus (#PCDATA)>

]>

<pagina>

<titulus>Catullus II</titulus>

<auctor>

<praenomen>Gaius</praenomen>

<nomen>Valerius</nomen>

<cognomen>Catullus</cognomen>

</auctor>

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

49

49

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

50

50

A logic program learned by GIFT

color_blind(Arg1) :start(Arg1,X),

p11(Arg1,X).

start(X,X).

p11(Arg1,P) :- mother(M,P),p4(Arg1, M).

p4(Arg1,X) :woman(X),father(F,X),p3(Arg1,F).

p4(Arg1,X) :woman(X),mother(M,X),p4(Arg1,M).

p3(Arg1,X) :- man(X),color_blind(X).

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

51

51

3 Hardness of the task

– One thing is to build algorithms,

another is to be able to state that

it works.

– Some questions:

–

–

–

–

Does this algorithm work?

Do I have enough learning data?

Do I need some extra bias?

Is this algorithm better than the

other?

– Is this problem easier than the other?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

52

52

Alternatives to answer these questions:

– Use well admitted benchmarks

– Build your own benchmarks

– Solve a real problem

– Prove things

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

53

53

Use well admitted benchmarks

• yes: allows to compare

• no: many parameters

• problem: difficult to better

(also, in GI, not that many

about!)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

54

54

Build your own benchmarks

• yes: allows to progress

• no: against one-self

• problem:

one

invents

the

benchmark where one is best!

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

55

55

Solve a real problem

• yes: it is the final goal

• no: we don’t always know why

things work

• problem:

how

much

pre-

processing?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

56

56

Theory

• Because you may want to be

able to say something more

than « seems to work in

practice ».

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

57

57

Identification in the limit

A class of languages

L

yields

Pres X

L

The naming function

A learner

G

A class of grammars

L((f))=yields(f) f()=g() yields(f)=yields(g)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

58

58

L is identifiable in the limit in terms of G

from Pres iff

LL, f Pres(L)

f1 f2

fn

fi

h1 h2

hn

hi hn

L(hi)= L

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

59

59

No quería componer otro Quijote —lo cual es fácil— sino

el Quijote. Inútil agregar que no encaró nunca una

transcripción mecánica del original; no se proponía

copiarlo. Su admirable ambición era producir unas páginas

que coincidieran palabra por palabra y línea por línea con

las de Miguel de Cervantes.

[…]

“Mi empresa no es difícil, esencialmente” leo en otro lugar

de la carta. “Me bastaría ser inmortal para llevarla a

cabo.”

Jorge Luis Borges(1899–1986)

Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote (El jardín de senderos que

se bifurcan) Ficciones

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

60

60

4 Algorithmic ideas

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

61

61

The space of GI problems

• Type of input (strings)

• Presentation of input (batch)

• Hypothesis space (subset of

the regular grammars)

• Success

criteria

(identification in the limit)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

62

62

Types of input

Structural

Examples:

Strings:

the

cat

hates

the

dog

(+)

cat

dog

the

the

hates

(-)

Graphs:

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

63

63

Types of input - oracles

• Membership queries

– Is string

language?

S

in

the

target

• Equivalence queries

– Is my hypothesis correct?

– If not, provide counter example

• Subset queries

– Is the language of my hypothesis

a subset of the target language?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

64

64

Presentation of input

• Arbitrary order

• Shortest to longest

• All

positive

and

negative

examples up to some length

• Sampled

according

to

some

probability distribution

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

65

65

Presentation of input

• Text presentation

– A presentation of all strings in

the target language

• Complete

(informant)

presentation

– A presentation of all strings

over the alphabet of the target

language labeled as + or Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

66

66

Hypothesis space

• Regular grammars

– A welter of subclasses

• Context free grammars

– Fewer subclasses

• Hyper-edge

grammars

replacement

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

graph

67

67

Success criteria

• Identification in the limit

– Text or informant presentation

– After

each

example,

learner

guesses language

– At some point, guess is correct

and never changes

• PAC learning

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

68

68

Theorem’s due to Gold

• The good news

– Any recursively enumerable class of

languages can be learned in the limit

from an informant (Gold, 1967)

• The bad news

– A language class is superfinite if it

includes all finite languages and at

least one infinite language

– No superfinite class of languages can

be learned in the limit from a text

(Gold, 1967)

– That includes regular and contextfree

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

69

69

A picture

DFA, from

queries

A lot of

information

Mildly context

sensitive, from

queries

DFA, from

pos+neg

Little

information

Sub-classes of

reg, from pos

Poor languages

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Context-free,

from pos

Rich Languages

70

70

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

71

71

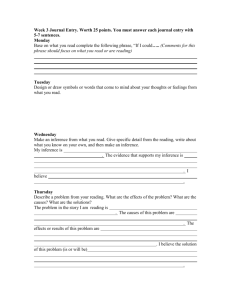

4.1 RPNI

• Regular Positive and Negative

Grammatical Inference

Identifying regular

in polynomial time

languages

Jose Oncina & Pedro García 1992

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

72

72

• It

is

a

state

algorithm;

• It

identifies

any

language in the limit;

• It works in polynomial

• It admits polynomial

teristic sets.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

merging

regular

time;

charac-

73

73

The algorithm

function rmerge(A,p,q)

A = merge(A,p,q)

while a, p,qA(r,a),

do

rmerge(A,p,q)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

pq

74

74

A=PTA(X); Fr ={(q0,a): a };

K ={q0};

While Fr do

choose q from Fr

if pK: L(rmerge(A,p,q))X-=

then A = rmerge(A,p,q)

else K = K {q}

Fr = {(q,a): qK} – {K}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

75

75

X+={, aaa, aaba, ababa, bb, bbaaa}

a

a

2

a

4

b

b

a

7

a

8

9

b

12

5

1

11

b

3

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

76

76

Try to merge 2 and 1

a

a

2

a

4

b

b

a

7

a

8

9

b

12

5

1

11

b

3

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

77

77

Needs more merging for determinization

a

a

a

b

1,2

4

b

a

7

a

11

8

9

b

12

5

b

3

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

78

78

But now string aaaa is

accepted, so the merge must be

rejected

a

9, 11

b

a

1,2,4,7

12

b

3,5,8

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

79

79

Try to merge 3 and 1

a

a

2

a

4

b

b

a

7

a

8

9

b

12

5

1

11

b

3

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

80

80

Requires to merge 6 with {1,3}

a

a

a

2

b

b

a

a

11

8

9

b

12

5

1,3

b

4

7

b

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

6

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

81

81

And now to merge 2 with 10

a

a

a

2

4

b

b

a

1,3,6

7

a

8

9

b

12

5

b

11

a

10

a

a

14

a

15

13

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

82

82

And now to merge 4 with 13

a

2,10

a

a

4

b

b

a

1,3,6

7

a

8

9

b

12

5

b

11

a

a

14

a

15

13

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

83

83

And finally to merge 7 with 15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

7

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

a

15

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

84

84

No counter example is accepted

so the merges are kept

7,15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

85

85

Next possible merge to be checked

is {4,13} with {1,3,6}

7,15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

86

86

More merging for determinization

is needed

7,15

a

a

b

2,10

a

1,3,4,6,13

a

b

11

8

a

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

87

87

But now aa is accepted

2,7,10,11,15

1,3,4,6,

8,13

a

a

b

a

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

88

88

So we try {4,13} with {2,10}

7,15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

89

89

After determinizing,

negative string aa is again accepted

a

a

1,3,6

2,4,7,10, b

13,15

a

b

9,11

b

a

14

12

5,8

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

90

90

So we try 5 with {1,3,6}

7,15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

91

91

But again we accept ab

7,15

4,13

2,9,10,14

a

1,3,5,6,12

a

a

b

a

11

8

b

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

92

92

So we try 5 with {2,10}

7,15

4,13

2,10

a

a

a

b

b

a

1,3,6

a

11

8

9

5

a

b

14

12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

93

93

Which is OK. So next possible merge

is {7,15} with {1,3,6}

7,15

4,9,13

2,5,10

a

a

11,14

a

a

b

1,3,6

b

8,12

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

94

94

Which is OK. Now try to merge

{8,12} with {1,3,6,7,15}

11,14

a

1,3,6,

7,15

4,9,13

b

a

8,12

a

a

a

2,5,10

b

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

95

95

And ab is accepted

a

1,3,6,7,

8,12,15

4,9,13

b

a

a

b

2,5,10,11,14

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

96

96

Now try to merge

{8,12} with {4,9,13}

11,14

a

1,3,6,

7,15

4,9,13

b

a

8,12

a

a

a

2,5,10

b

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

97

97

This is OK and no more merge

is possible so the algorithm halts.

a

1,3,6,7,

11,14,15

4,8,9,12,13

b

a

a

a

2,5,10

b

b

X-={aa, ab, aaaa, ba}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

98

98

Definitions

• Let

be

the

length-lex

ordering over *

• Let Pref(L) be the set of all

prefixes of strings in some

language L.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

99

99

Short prefixes

Sp(L)={uPref(L):

(q0,u)=(q0,v) uv}

• There is one short prefix per

useful state

b

0

Sp(L)={, a}

a

a

1

b

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

2

b

a

100

10

Kernel-sets

• N(L)={uaPref(L): uSp(L)}{}

• There is an element in the

Kernel-set

for

each

useful

transition

b

0

N(L)={, a, b, ab}

a

a

1

b

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

2

b

a

101

10

A characteristic sample

•A

sample

is

(for RPNI) if

characteristic

– xSp(L) xuX+

– xSp(L), yN(L),

(q0,x)(q0,y)

z*:

xzX+yzX-

xzX-yzX+

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

102

10

About characteristic samples

• If you add more strings to a

characteristic sample it still is

characteristic;

• There

can

be

many

different

characteristic samples;

• Change

the

ordering

(or

the

exploring function in RPNI) and

the characteristic sample will

change.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

103

10

Conclusion

• RPNI

identifies

any

regular

language in the limit;

• RPNI works in polynomial time.

Complexity is in O(║X+║3.║X-║);

• There

are

many

significant

variants of RPNI;

• RPNI can be extended to other

classes of grammars.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

104

10

Open problems

• RPNI’s complexity is not a

tight upper bound. Find the

correct complexity.

• The

definition

of

the

characteristic

set

is

not

tight either. Find a better

definition.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

105

10

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

106

10

4.2 The k-reversible languages

• The class was proposed by Angluin

(1982).

• The class is identifiable in the

limit from text.

• The class is composed by regular

languages that can be accepted by

a DFA such that its reverse is

deterministic

of k.

with

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

a

look-ahead

107

10

Let A=(, Q, , I, F) be a NFA,

we denote by AT=(, Q, T, F,

I) the reversal automaton

with:

T(q,a)={q’Q: q(q’,a)}

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

108

10

a

A

0

a

1

a

2

a

3

4

a

a

1

a

b

a

AT

0

b

2

a

3

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

a

b

b

4

109

10

Some definitions

• u is a k-successor of q if

│u│=k and (q,u).

• u is a k-predecessor of q if

│u│=k and T(q,uT).

•

is

0-successor

and

0predecessor of any state.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

110

11

a

A

0

a

1

a

2

a

3

a

b

b

4

• aa is a 2-successor of 0 and

1 but not of 3.

• a is a 1-successor of 3.

• aa is a 2-predecessor of 3

but not of 1.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

111

11

A NFA is deterministic with

look-ahead k iff q,q’Q:

qq’

(q,q’I) (q,q’(q”,a))

(u is a k-successor of q)

(v is a k-successor of q’)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

uv

112

11

Prohibited:

u

1

│u│=k

a

a

u

2

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

113

11

Example

a

a

0

1

a

2

a

3

a

b

b

4

This

automaton

is

not

deterministic with look-ahead

1 but is deterministic with

look-ahead 2.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

114

11

K-reversible automata

• A is k-reversible if A is

deterministic

and

AT

is

deterministic with look-ahead k.

• Example

0

a

b

b

a

1

b

deterministic

b

2

0

a

a

1

b

2

b

deterministic with look-ahead 1

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

115

11

Violation of k-reversibility

• Two states q, q’ violate the

k-reversibility condition iff

– they violate the deterministic

condition: q,q’(q”,a);

or

– they

violate

the

look-ahead

condition:

• q,q’F, uk: u is k-predecessor of

both;

• uk, (q,a)=(q’,a) and u is kpredecessor of both q and q’.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

116

11

Learning k-reversible automata

• Key idea: the order in which

the merges are performed does

not matter!

• Just merge states that do not

comply with the conditions

for k-reversibility.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

117

11

K-RL Algorithm (k-RL)

Data: k, X sample of a k-RL L

A=PTA(X)

While

q,q’

k-reversibility

violators do

A=merge(A,q,q’)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

118

11

k=2

Let X={a, aa, abba, abbbba}

a

a

aa

abba

a

a

b

ab

b

abb

b

abbb

b

abbbb

a

abbbba

Violators, for u= ba

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

119

11

Let X={a, aa, abba, abbbba}

a

a

aa

abba

a

a

b

ab

k=2

b

abb

a

b

abbb

b

abbbb

Violators, for u= bb

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

120

12

Let X={a, aa, abba, abbbba}

a

a

aa

abba

a

a

b

ab

b

abb

k=2

b

b

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

abbb

121

12

Properties (1)

• k0, X, k-RL(X) is a kreversible language.

• L(k-RL(X)) is the smallest kreversible

language

that

contains X.

• The class Lk-RL is identifiable

in the limit from text.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

122

12

Properties (2)

• Any regular language is kreversible iff

(u1v)-1L (u2v)-1L and │v│=k

(u1v)-1L=(u2v)-1L

(if two strings are prefixes of a string

of length at least k, then the strings

are Nerode-equivalent)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

123

12

Properties (3)

• Lk-RL(X) L(k+1)-RL(X)

• Lk-TSS(X) L(k-1)-RL(X)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

124

12

Properties (4)

The time complexity is O(k║X║3).

The space complexity is O(║X║).

The algorithm is not incremental.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

125

12

Properties (4)

Polynomial aspects

• Polynomial characteristic sets

• Polynomial update time

• But

not

necessarily

a

polynomial

number

of

mind

changes

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

126

12

Extensions

• Sakakibara built an extension for

context-free grammars whose tree

language is k-reversible

• Marion

&

Besombes

propose

an

extension to tree languages.

• Different authors propose to learn

these automata and then estimate

the probabilities as an alternative

to learning stochastic automata.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

127

12

Exercises

• Construct a language L that

is not k-reversible, k0.

• Prove that the class of kreversible languages is not

in TxtEx.

• Run k-RL on X={aa, aba, abb,

abaaba, baaba} for k=0,1,2,3

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

128

12

Solution (idea)

• Lk={ai: ik}

• Then for each k: Lk is kreversible

but

not

k-1reversible.

• And

ULk

= a*

• So there

point…

is

an

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

accumulation

129

12

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

130

13

4.4 Active Learning:

learning DFA from membership and

equivalence queries: the L* algorithm

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

131

13

The classes C and H

• sets of examples

• representations of these sets

• the computation of L(x) (and

h(x)) must take place in time

polynomial in x.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

132

13

Correct learning

A class C is identifiable with a

polynomial number of queries of

type

T if there exists an

algorithm that:

1) LC identifies L with a polynomial

number of queries of type T;

2) does each update in time polynomial

in f and in xi, {xi} counterexamples seen so far.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

133

13

Algorithm L*

• Angluin’s papers

• Some talks by Rivest

• Kearns and Vazirani

• Balcazar,

Diaz,

Gavaldà

Watanabe

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

&

134

13

Some references

• Learning regular sets from queries

and counter-examples, D. Angluin,

Information and computation, 75,

87-106, 1987.

• Queries and Concept learning, D.

Angluin, Machine Learning, 2, 319342, 1988.

• Negative results for Equivalence

Queries,

D.

Angluin,

Machine

Learning, 5, 121-150, 1990.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

135

13

The Minimal Adequate Teacher

• You are allowed:

– strong equivalence queries;

– membership queries.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

136

13

General idea of L*

• find

a

consistent

table

(representing a DFA);

• submit it as an equivalence query;

• use counterexample to update the

table;

• submit membership queries to make

the table complete;

• Iterate.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

137

13

An observation table

a

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

0

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

138

13

The experiments (E)

a

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

0

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

The states (S)

or test set

The transitions (T)

139

13

Meaning

a

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

0

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

(q0, . )F

L

140

14

a

1

0

0

0

b 1

aa 0

ab 1

0

0

0

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

(q0, ab.a) F

aba L

141

14

Equivalent prefixes

a

1

0

0

0

b 1

aa 0

ab 1

0

0

0

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

These two rows

are equal,

hence

(q0,)= (q0,ab)

142

14

Building a DFA from a table

a

1

0

0

0

b 1

aa 0

ab 1

0

0

0

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

a

a

143

14

b

a

1

0

0

0

b 1

aa 0

ab 1

0

0

0

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

b

a

a

a

144

14

Some rules

This set is suffix-closed

b

a

This

set is

prefixclosed

S\S=T

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

0

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

b

a

a

a

145

14

An incomplete table

b

a

a

b

aa

ab

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

b

a

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

a

146

14

Good idea

We can complete the table

making membership queries...

v

u

by

Membership query:

?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

uvL ?

147

14

A table is

closed

if

any

row

of

T

corresponds to some row in S

a

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

1

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Not closed

148

14

And a table that is not closed

b

a

a

1

0

0

0

b

aa

ab

1

0

1

0

1

0

b

a

a

a

?

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

149

14

What do we do when we have a table that

is not closed?

• Let s be the row (of T) that

does not appear in S.

• Add s to S, and a sa to T.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

150

15

An inconsistent table

a

a

b

aa

ab

ba

bb

1

0

0

1

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Are a and b

equivalent?

151

15

A table is consistent if

Every equivalent pair of rows

in H remains equivalent in S

after appending any symbol

row(s1)=row(s2)

a, row(s1a)=row(s2a)

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

152

15

What do we do when we have an

inconsistent table?

Let

a

be

row(s1)=row(s2)

row(s1a)row(s2a)

such

that

but

• If row(s1a)row(s2a), it is so

for experiment e

• Then add experiment ae to the

table

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

153

15

What do we do when we have a closed and

consistent table ?

• We build the corresponding DFA

• We make an equivalence query!!!

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

154

15

What do we do if we get a counterexample?

• Let u be this counter-example

• wPref(u) do

– add w to S

– a, such that waPref(u) add

wa to T

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

155

15

Run of the algorithm

1

a

1

b

1

b

Table is now

closed

and consistent

a

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

156

15

An equivalence query is made!

b

a

Counter example baa is returned

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

157

15

b

ba

baa

1

1

1

0

a

bb

bab

baaa

baab

1

1

1

0

1

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

Not

consistent

Because of

158

15

a

b

ba

baa

1

1

1

0

1

1

0

0

a

bb

bab

baaa

baab

1

1

1

0

1

0

1

1

0

0

Table is now

closed

and

consistent

b

a ba

b

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

b

a

a

baa

159

15

Proof of the algorithm

Sketch only

Understanding the proof is important

for further algorithms

Balcazar et al. is a good place for that.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

160

16

Termination / Correctness

• For every regular language there is

a unique minimal DFA that recognizes

it.

• Given a closed and consistent table,

one can generate a consistent DFA.

• A DFA consistent with a table has at

least as many states as different

rows in S.

• If the algorithm has built a table

with n different rows in S, then it

is the target.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

161

16

Finiteness

• Each closure failure adds one

different row to S.

• Each inconsistency failure adds

one

experiment,

which

also

creates a new row in S.

• Each counterexample adds one

different row to S.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

162

16

Polynomial

• |E| n

• at most n-1 equivalence queries

• |membership queries| n(n-1)m

where m is the length of the

longest counter-example returned

by the oracle

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

163

16

Conclusion

• With an MAT you can learn DFA

– but also a variety of other classes of

grammars;

– it is difficult to see how powerful is really

an MAT;

– probably as much as PAC learning.

– Easy to find a class, a set of queries and

provide and algorithm that learns with them;

– more difficult for it to be meaningful.

• Discussion:

meaningful?

why

are

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

these

queries

164

16

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

165

16

4.5 SEQUITUR

(http://sequence.rutgers.edu/sequitur/)

(Neville Manning & Witten, 97)

Idea: construct a CF grammar

from a very long string w,

such that L(G)={w}

– No generalization

– Linear time (+/-)

– Good compression rates

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

166

16

Principle

The grammar with respect to the

string:

– Each rule has to be used at

least twice;

– There can be no sub-string of

length 2 that appears twice.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

167

16

Examples

Sabcdbc

S aAdA

A bc

SAaA

A aab

Saabaaab

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

SAbAab

A aa

168

16

abcabdabcabd

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

169

16

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the

earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and

darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the

Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was

light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God

divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he

called Night. And the evening and the morning

were the first day.

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the

midst of the waters, and let it divide the

waters from the waters.

And God made the firmament, and divided the waters

which were under the firmament from the waters

which were above the firmament: and it was so.

And God called the firmament Heaven. And the

evening and the morning were the second day.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

170

17

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

171

17

Sequitur options

• appending a symbol to rule S;

• using an existing rule;

• creating a new rule;

• and deleting a rule.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

172

17

Results

On text:

– 2.82 bpc

– compress 3.46 bpc

– gzip 3.25 bpc

– PPMC 2.52 bpc

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

173

17

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

174

17

4.6 Using a simplicity bias

(Langley & Stromsten, 00)

Based on algorithm GRIDS

(Wolff, 82)

Main characteristics:

– MDL principle;

– Not characterizable;

– Not tested on large benchmarks.

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

175

17

Two learning operators

Creation of non terminals and rules

NP ART ADJ NOUN

NP ART ADJ ADJ NOUN

NP ART AP1

NP ART ADJ AP1

AP1 ADJ NOUN

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

176

17

Merging two non terminals

NP ART AP1

NP ART AP2

AP1 ADJ NOUN

AP2 ADJ AP1

NP ART AP1

AP1 ADJ NOUN

AP1 ADJ AP1

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

177

17

• Scoring

function:

principle: G+wT d(w)

MDL

• Algorithm:

– find best merge that improves

current grammar

– if no such merge exists, find

best creation

– halt when no improvement

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

178

17

Results

• On

subsets

of

English

grammars (15 rules, 8 non

terminals, 9 terminals): 120

sentences to converge

• on (ab)*: all (15) strings of

length 30

• on Dyck1: all (65) strings of

length 12

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

179

17

Algorithms

RPNI

K-Reversible

L*

SEQUITUR

GRIDS

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

180

18

5 Open questions and conclusions

• dealing with noise

• classes

of

languages

that

adequately mix Chomsky’s hierarchy

with edit distance compacity

• stochastic context-free grammars

• polynomial learning from text

• learning POMDPs

• fast algorithms

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

181

18

Intuí que había caído en una trampa y quise huir. Hice un enorme esfuerzo,

pero era tarde: mi cuerpo ya no me obedecía. Me resigné a presenciar lo que

iba a pasar, como si fuera un acontecimiento ajeno a mi persona. El hombre

aquel comenzó a transformarme en pájaro, en un pájaro de tamaño humano.

Empezó por los pies: vi cómo se convenían poco a poco en unas patas de gallo

o algo así. Después siguió la transformación de todo el cuerpo, hacia arriba,

como sube el agua en un estanque. Mi única esperanza estaba ahora en los

amigos, que inexplicablemente no habían llegado. Cuando por fin llegaron,

sucedió algo que me horrorizó: no notaron mi transformación. Me trataron como

siempre, lo que probaba que me veían como siempre. Pensando que el mago

los ilusionaba de modo que me vieran como una persona normal, decidí referir

lo que me había hecho. Aunque mi propósito era referir el fenómeno con

tranquilidad, para no agravar la situación irritando al mago con una reacción

demasiado violenta (lo que podría inducirlo a hacer algo todavía peor), comencé

a contar todo a gritos. Entonces observé dos hechos asombrosos: la frase que

quería pronunciar salió convertida en un áspero chillido de pájaro, un chillido

desesperado y extraño, quizá por lo que encerraba de humano; y, lo que era

infinitamente peor, mis amigos no oyeron ese chillido, como no habían visto mi

cuerpo de gran pájaro; por el contrario, parecían oír mi voz habitual diciendo

cosas habituales, porque en ningún momento mostraron el menor asombro. Me

callé, espantado. El dueño de casa me miró entonces con un sarcástico brillo en

sus ojos, casi imperceptible y en todo caso sólo advertido por mí. Entonces

comprendí que nadie, nunca, sabría que yo había sido transformado en pájaro.

Estaba perdido para siempre y el secreto iría conmigo a la tumba.

ERNESTO SÁBATO, EL TÚNEL

Erice 2005, the Analysis of Patterns. Grammatical Inference

182

18