PPT - Environmental Literacy

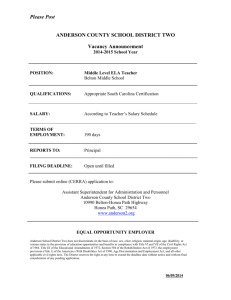

advertisement

Some Good Books I Can Recommend Distinguished Contributions Award Presentation Andy Anderson NARST Conference, 2013 Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions • On what basis can we claim that scientific knowledge is “true?” • What do we mean by “true?” • First conference presentation: First Conference Presentation Anderson, C.W. (1979, April). The evolution controversy: Is science a religion? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Atlanta, GA. • I know that I am right about evolution. • Creationists know that they are right. • On what basis can we privilege one person’s certainty over another’s? Good, T. & Brophy, J. Looking in Classrooms • What works in classroom teaching? • How can we help students learn with understanding? • Where does science content fit in? • Dissertation: observational study of science classrooms Reading at MSU Mayr, E. (1982). The growth of biological thought. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Toulmin, S. (1961). Foresight and understanding. Great Britain: The Anchor Press, Ltd. Toulmin, S. (1972). Human understanding. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. • History of science as evolution of “intellectual ecologies” • Utility rather than truth as a basis for privileging particular knowledge and practices. Conceptual Change Eric McWilliams and Mary Budd Rowe: RISE PI meeting, Carnegie Mellon University, 1980. Posner, J., Strike, K., Hewson, P., & Gertzog, W. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66, 211-227. • We can study what students say in ways similar to how we study what professors say. • I can do this! Light from the sun helps the girl to see the tree. How does it do this? Adapted from Transparencies on Light: Teachers’ Manual. 1983. Anderson, Charles W. & Edward L. Smith. The Institute for Research on Some of the light bounces (is reflected) off the tree and goes to the girl’s eyes. Adapted from Transparencies on Light: Teachers’ Manual. 1983. Anderson, Charles W. & Edward L. Smith. The Institute for Research on Bishop, B.A., & Anderson, C.W. (1990). Student conceptions of natural selection and its role in evolution. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 27(5), 415-427 Last Conceptual Change Article • Lee, O., Eichinger, D., Anderson, C. W., Berkheimer, G. D., & Blakeslee, T. D. (1993). Changing middle school students' conceptions of matter and molecules. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 30(3), 249-270. • Matter and Molecules unit Social and Experiential Learning Wertsch, J. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. • How are knowledge, practice, and language interconnected? • How do we learn from other people? • National languages and social languages. Michigan Essential Goals and Objectives for Science Education (1991) Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. • How is our knowledge embedded in our practices and ways of talking? • How is privilege passed from one generation to the next? • How can we tap into students’ funds of knowledge? Language, Identity, and Learning • Discourse: “a socially accepted association among ways of using language, of thinking, and of acting that can be used to identify oneself as a member of a socially meaningful group” (Gee, J. P. (1991). What is literacy? In C. Mitchell and K. Weiler (eds.), Rewriting literacy: Culture and the discourse of the other. New York: Bergin & Garvey, p. 3) • Kurth, L., Anderson, C. W., & Palincsar, A. S. (2002). The case of Carla: Dilemmas of helping all students to understand science. Science Education, 86(3), 287-313. Some New Ideas • Environmental science literacy as a way to address the “depth vs. breadth” problem: citizenship as a core goal of science education • Learning progressions as a way to integrate cognitive and sociocultural insights (but still more cognitive than sociocultural) Pinker, S. (2007). The stuff of thought: Language as a window into human nature • There is a theory of space and time embedded in the way we use words. There is a theory of matter and causality, too. … These conceptions… add up to a distinctively human model of reality, which differs in major ways from the objective understanding of reality eked out by our best science and logic. Though these ideas are woven into language, their roots are deeper than language itself. They lay out the ground rules for how we understand our surroundings… Pinker, The Stuff of Thought, page vii. Contrasts between Force-dynamic and Scientific Discourse (Pinker, Talmy) • Force-dynamic discourse: Actors (e.g., animals, plants, machines) make things happen with the help of enablers that satisfy their “needs.” – This is everyone’s “first language” that we have to master in order to speak grammatical English (or French, Spanish, Chinese, etc.) • Scientific discourse: Systems are composed of enduring entities (e.g., matter, energy) which change according to laws or principles (e.g., conservation laws) – This is a “second language” that is powerful for analyzing the material world • We often have the illusion of communication because speakers of these languages use the same words with different meanings (e.g., energy, carbon, nutrient, etc.) Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow: The Psychology of False Certainty Metaphor of our minds working with a dual processing system: • System 1 (thinking fast) instantly and subconsciously fits what we see and know about the world into perceptions and narrative frameworks. • System 2 (thinking slow) allows us with conscious effort to question and modify the perceptions and narratives that System 1 gives to us. Advantages of System 1 • Enables quick, decisive action based on incomplete data • Enables us to persist when the odds are against us Problems with System 1 • Sometimes wrong • Is just as certain when we are wrong as when we are right Characteristics of System 1 1. WYSIATI: What You See Is All There Is 2. Substituting an easier question 3. Source amnesia. 4. Confirmation bias 5. Stories, not statistics 6. False certainty Relationship between System 1 and System 2 • System 1 always processes first, producing perceptions and stories that are sometimes wrong but always subjectively certain • System 2 sometimes adds doubts and reconsider • Note temporal order: Certainty precedes doubt Scientific Inquiry: Reversing the Temporal Order Scientific inquiry is a collective process that puts System 2 in charge • Assume all knowledge claims are initially uncertain • Study and quantify uncertainty (error bars, inferential statistics) • Communicate about uncertainty (e.g., by how sources are cited) • Follow strategies to reduce uncertainty • Giving authority to arguments from evidence rather than individual people • Commitment to rigor in research methods • Collective validation through consensus of scientific communities (peer review) • Identifying sources for knowledge claims Where are we now? • Science education has never been as important as it is today. • We need to mount a national response to an existential threat: climate change • Scientific literacy can play a key role in that response • We have conceptual tools that we didn’t have at the start of my career