Scoping paper EUKN Policy Lab

advertisement

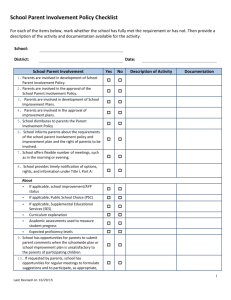

Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus Factsheet EUKN Cyprus Policy Lab Compact City Planning 1. Introduction The Cyprus Policy Lab, May 2015, will explore the theme of compact city planning instruments in relation with some of the current planning challenges in Cyprus. The Cyprus government regulates and manages development in urban areas mainly through local plans and using a limited number of regulatory and development control tools. The government’s involvement in actual land development remains very limited. A qualitative assessment of urban development in Cyprus urban areas shows an unbalanced growth and a failure to meet the development goals and objectives set by local plans. This situation is primarily due to a poor performance of the private sector and a lack of enforcement tools, incentives and coordination mechanisms on the governmental side.1 This situation calls for more institutional provisions and government involvement in land and urban development processes in Cyprus. This policy lab will explore different compact city planning strategies that could help the government in Cyprus to play a more active role in achieving the local plan objectives, to introduce sustainable practices in urban development, and to overcome urban sprawl and its negative effects. During the Policy Lab, the topic will be examined and analysed through examples and experiences of other European countries. This Factsheet provides background information on the concept of compact city planning and relevant structures, policies and experiences at European level and in some Member States. The factsheet concludes with some good practices that can serve as inspiration for the discussion during the Policy Lab and for improving planning structures and policies in Cyprus. The policy lab will explore the following questions: 1. What are the incentives that local/ planning authorities can provide to the private sector to play a more active role in sustainable urban development in Cyprus in general and to achieve the objectives of local development plans in particular? 2. What are the policy tools that can improve the practice of urban planning in Cyprus and promote sustainable development of Cypriot urban areas? 2. Compact cities: concept, approach and instruments The compact city is one of the most discussed concepts in contemporary urban planning policy. The concept receives renewed attention in the context of the development of a new urban agenda for 1 See: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/funds/2007/jjj/doc/pdf/jessica/cy_jessica_evaluation.pdf 1 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus sustainable urban development at the global level within UN Habitat III. 2 Although a number of definitions exist, a compact city is considered to be: i) dense and proximate development patterns; ii) urban areas linked by an efficient public transport systems; and iii) accessibility to local services and jobs, according to the OECD report on compact city policies.3 First of all, urban density involves how intensively urban land is utilised, and proximity particularly concerns the location of urban agglomerations in a metropolitan area. In a compact city, urban land is intensively utilised and the border between urban and rural land use at the urban fringe is clear. However, public spaces including squares, streets and parks are also essential elements. Secondly, urban areas linked by efficient public transport systems indicate how effectively urban land is utilised. Public transport systems facilitate mobility in urban areas and enable urban areas to function effectively. Thirdly, accessibility to local services and jobs concerns how easily residents can reach local services such as grocery stores, restaurants and clinics as well as neighbourhood jobs. In a compact city, land use is mixed and most residents have access to these services either on foot or bike or using public transport.4 Compact cities can contribute to urban sustainability and growth in several ways. Based on the key characteristics of the compact city, the OECD report5 identifies the following contributions: i) shorter intra-urban travel distances; ii) less automobile dependency; iii) more district-wide energy utilisation and local energy generation; iv) optimal use of land resources and more opportunity for urban-rural linkages; v) more efficient public services delivery; and vi) better access to a diversity of local services and jobs.6 The compact city concept has also generated concerns about potential adverse effects of compact cities (see OECD 2012): traffic congestion, air pollution, housing affordability, quality of life, urban heat islands, loss of open and recreational spaces. These potential adverse effects have to be taken into account in the planning process (see figure 1, key point 5). In short, the concept of compact city should be applied within the broader framework of sustainable urban development. 2 See: http://unhabitat.org/urbaninsight/newsletter_1502_feb15.html Compact cities allow for more people to live closer to public spaces, places of work and amenities such as schools, hospitals, shops and community facilities. A dense layout increases the efficiency of public transport, saves commuting time and promotes healthy and green non-motorized mobility such as walking and cycling. 3 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 4 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing, pp.26-28. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 5 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 6 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing, p.59. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 2 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus 2.1 Urban sprawl as a challenge for today’s cities The term “compact city” has often been discussed as the contrary of “urban sprawl”. This term is often used rather negatively, typically to describe low density, inefficient, suburban development around the periphery of cities. Urban sprawl has several consequences in terms of transport, density, accessibility of services and conversion of rural to urban land. By definition sprawl leads to greater distances between homes, between homes and jobs and between urban activities generally, generating more demand for travel and expenditure on improving transport systems. Secondly, sprawl leads to changes in urban densities, most commonly a reduction in densities in the urban core and an increase in densities towards the periphery. Thirdly, urban sprawl usually involves the conversion of previously rural land into urban use. Urban sprawl has been a matter of policy and planning ever since it has been acknowledged as a particular pattern of spatial development. The desire to control the dynamics of urban sprawl was one of the earliest motivations for state intervention in spatial development. There is a remarkable consensus between different European countries and societies and between different levels of government about the overall aims of policy with regard to urban sprawl: the need to control urban sprawl and develop more compact cities is generally accepted by governments across Europe.7 2.2 Current practices of compact city policies Implementing the compact city model is particularly reliant on policy cutting across different urban scales and sectors. It includes a focus on urban regeneration, the revitalisation of urban cores, and the promotion of public and non-motorized transport; extensive environmental controls and high standards of urban management. Compact city policy has relied heavily on spatial planning and investment strategies involving three top-level policy targets: higher urban densities, mixed-use and urban design quality. They are usually implemented on an urban scale, with provision of public transport, often by direct government interventions.8 Current practices of compact city policies can be summarized by different types of intervention (regulatory, fiscal, direct investment, partnership, informative). Most common interventions in OECD countries include: 7 The compact city is a part of many master plans and strategic plans both at the city, metropolitan and at the national level. Regulatory tools seem to be the instrument the most widely used for compact cities. Among the most popular are urban growth boundaries (also known by terms such as urban containment boundary) and greenbelts, which aim to limit urban development beyond Pichler-Milanovic, N. (2008). European Urban Sprawl. 44th ISOCARP Congress. 8 Rode, Philipp (2013) The politics and planning of urban compaction: the case of the London Metropolitan region. In: 4th Holcim Forum 2013 – “Economy of Sustainable Construction”, 11-13 April 2013, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT Bombay), Mumbai, India 3 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus boundaries and in greenbelts. Density requirements and mixed-use requirements are increasingly popular regulatory tools. As an example, to impose minimum density requirements on new construction near sites with existing or planned transport services. A sub-density tax is imposed on development that does not meet the requirements. Mixed-use requirements are also used. Fiscal tools have also been proposed as effective measures for spatial development policy and there is a variety of fiscal programmes for compact cities. In many countries, subsidies and other fiscal incentives are used for the conversion and renovation of existing buildings to provide more housing in urban centres. Direct government intervention through investment in city projects is widely used to create attractive public spaces. These projects are also carried out in co-operation with the private sector under various schemes including public-private partnerships (PPPs). Development agreements between a private developer and the planning authority can play a similar role in a private development project.9 2.3 Policy strategies The compact city concept offers an extensive direct role for the government in the production of the built environment. The following five key points summarizes the most important policy strategies based on the findings and assessments of current compact city policies in OECD countries: 9 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing, p.119-120. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 4 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus Figure 1: Key policy strategies and sub-strategies for the compact city, source: OECD, 2012 3. Spatial planning at EU level At EU-level, territorial cohesion is a key concept that can be related to spatial and balanced territorial development in Europe. The most influential declarations are the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) in 1999, the Territorial Agenda of the European Union and the Leipzig Charter on sustainable European cities in 2007, and the revised Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020 (TA2020) of 2011.10 Cohesion, coherence and cooperation are key concepts in the European spatial planning and territorial cohesion policy.11 The European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP), agreed at the Informal Council of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning in Potsdam, May 1999, summarizes the guidelines for national spatial development policies. Development of the EU is based on three key goals: economic and social cohesion; conservation and management of natural resources and cultural heritage; and more 10 See: http://ntccp-udg.eu/ntccp 11 A. Faludi (2010) Andreas Faludi European Spatial Planning: Past, Present and Future 5 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus balanced competitiveness of the European territory. In order to move towards these goals, the ESDP advocates three key policy guidelines: • the development of a balanced and polycentric urban system and a new urban- rural relationship; • securing parity of access to infrastructure and knowledge; • sustainable development, prudent management and protection of nature and cultural heritage (ESDP, 1999, p.11). While ESDP impacts three levels of actors – institutions of EU, Member States and sub-national actors – it focuses primarily on the latter. The EU role is to coordinate and establish a forum, rather than implementing. Urban and territorial planning is not an EU competency; the ESDP recommendations are not binding. Most of ESDP’s recommendations foster action on a city-region or region-wide scale. The TA2020, agreed at the Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development on 19th May 2011 Gödöllő, Hungary, builds on the ESDP of 1999. The TA2020 identifies six territorial priorities, including balanced, polycentric territorial development and the use of integrated development approaches for urban and regional development. Together ESDP and TA2020 create the “catalyst environment” where national planning systems can position themselves.12 In the past two decades in Europe, there has been a shift to a more strategic, development-oriented spatial planning approach, aiming at better coordination of economic planning, regional development, and sectoral policies. The shift represents the need to facilitate investments, and to involve private stakeholders to territorial governance. Strategic objectives incorporate sustainability principles, while public policies need to improve horizontal and vertical coordination. Overall, new planning modes are more strategic and proactive, enabling multi-actor participation and networking on different levels. Modes can be both formal and informal, enhancing flexibility and economic-led programming. They are introduced as innovative planning modes that do not overwrite the existing modes and tools of the mainstream planning system. Since the 1990s, devolution of planning power moved from central level to lower administration levels in Europe. 13 However, a countertendency of recentralization to the central state is also present, especially in crucial policy areas such as environment, water resources, crisis management, or housing. Vertical restructuring shows different tendencies. In some EU countries (e.g. Greece, Italy, Poland) regions are gaining planning power, while in other countries (e.g. Denmark, UK) the local level (municipalities) have strengthened. Source? Multi-actor involvement has been among the main objectives since the 1990s, reflecting the shift from government to governance. Main actors – who want to trigger change – form coalitions against the mainstream planning system, consisting of politicians, public servants, mayors, planners, experts, 12 Reimer, M., Getimis, P. and Blotevogel, H. (2014). Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe. New York, NY: Routledge, pp.5-8. 13 Rei Reimer, M., Getimis, P. and Blotevogel, H. (2014). Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe. New York, NY: Routledge, pp.281-296. 6 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus academic community, private stakeholders, NGOs and citizens (as discussed in the Cyprus Policy Lab in 2013 on participatory planning). The scope of territorial governance implies the active involvement of all interested parties, but mainly political personnel and associations of planners take yet initiative. Considering the central-local relations, in hierarchical, top-down planning systems (e.g. Poland and Greece) the central state is the “architect” of the planning reform, while more decentralized systems with a long tradition of municipal power (e.g. Denmark and Germany), associations of municipalities and planners have very decisive roles at all stages of urban planning (initiative, agenda setting, implementation). A common trend concerning the changes of planning styles can be observed: consensus features are emerging, and the planning process is opening up to new stakeholders. Even hierarchical, “command and control” planning styles, such as Greece or Poland show orientation towards consultation, networking and collaboration, although the mainstream “command and control” planning system is not abandoned.14 4. The current urban planning instruments in Cyprus 4.1 The planning system in Cyprus Economic and regional development policy in Cyprus is based on indicative planning, exercised through the Planning Bureau on the one hand: an independent directorate under the authority of the Minister of Finance, which formulates long-term development policy at the strategic level and exercises control over its implementation through the state budget. On the other hand, responsibility for spatial planning and urban policy rests with the Minister of Interior, who has delegated certain of his responsibilities to the larger Municipalities, the Department of Town Planning and Housing, as well as the Planning Board, an independent body with advisory power over large areas of planning policy. A three-tier hierarchy of development plans is based on the concepts of the “Island Plan,” which refers to the national territory and the regional distribution of resources and development opportunities, the “Local Plan,” for major urban areas or regions undergoing intensive development pressures, and the “Area Scheme,” at the lower end of the hierarchy.15 4.2 The Department of Town Planning and Housing Under the Ministry of the Interior, the Department of Town Planning and Housing, is the national directorate responsible for the implementation of the Town and Country Planning legislation and aspects of urban policy and spatial planning. The Department comprises the Sections of Housing (responsible for national housing policy, as well as the design and management of public housing, at present almost exclusively serving refugees displaced by the 1974 Turkish invasion), Development 14 Reimer, M., Getimis, P. and Blotevogel, H. (2014). Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe. New York, NY: Routledge, pp.294-295. 15 Rochfordessex.com, (2015). The Planning System in Cyprus ~ The Cyprus Informer. [online] Available at: http://rochfordessex.com/informer/property-regulations/the-planning-system-in-cyprus/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2015]. 7 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus Control (responsible for plan implementation and enforcement, as well as providing the administration for six of the nation’s Planning Authorities) and Spatial Planning (responsible for urban and spatial policy formulation, including issues of land use, preservation, transportation and territorial development). In addition, the Department provides personnel and advice to the Nicosia Master Plan, a bi-communal ground breaking institution involving both the Greek- and TurkishCypriot communities of the divided capital.16 4.3 Current issues Major territorial challenges affecting Cyprus today include the continued physical division of the island and the persistence of a dividing line, the decline of historic urban centres, the gradual abandonment of mountain villages, continued urban dispersal and associated peri-urban sprawl, lagging implementation of nature protection and insufficient agricultural restructuring. These problems are especially evident in the countryside and at the urban fringe, where new development continually encroaches on prime agricultural land and areas rich in natural and cultural resources. Problems besetting urban areas are complex and varied. The expansion of cities has been followed, as elsewhere, by the deterioration and disintegration of historic urban cores due to the exodus of populations and businesses towards areas with a more competitive edge because of better accessibility and infrastructure availability, especially in areas adjacent to the dividing line in Nicosia. This gradual abandonment has in turn led to a fall in the quality of the urban environment, accompanied in recent years by an influx of migrant workers and a more general deterioration of social and economic conditions, as well as an unwillingness of the private sector to invest in the improvement of the urban fabric. To address such problems, a broad set of Integrated Urban Regeneration measures for the improvement of the urban environment and cultural infrastructure are currently being implemented through partnerships of central government agencies and local authorities. Actions include the rehabilitation of buildings and street elevations, the development of networks of pedestrian ways, bicycle trails and green spaces, as well as the creation of cultural centres and care centres for the elderly and children.17 5. Compact city policies in some other member states 5.1 The Netherlands In the Netherlands, since 2006, the National Spatial Strategy and the Frame of Reference on Urbanisation set the national framework for spatial planning. The framework was established in 16 Rochfordessex.com, (2015). The Planning System in Cyprus ~ The Cyprus Informer. [online] Available at: http://rochfordessex.com/informer/property-regulations/the-planning-system-in-cyprus/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2015]. 17 Rochfordessex.com, (2015). The Planning System in Cyprus ~ The Cyprus Informer. [online] Available at: http://rochfordessex.com/informer/property-regulations/the-planning-system-in-cyprus/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2015]. 8 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus 2001, and the current document was released in 2009, although the compact city concept was already an issue in 1970s. The document provides for cities that are sustainable, more compact build, less urban sprawl and restructuring of brownfield areas. At the same time, attention is paid to energy and climate change. The policy according to the document of 2009 states that to achieve the sustainable development of these areas, a spatial strategy of more compact construction and less urban sprawl will be necessary. The framework is administered by the new Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment. The provinces and cities base their spatial plans on this framework. Most big cities such as The Hague, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht have compact city policies. Often these policies are more ambitious than what is required in the Reference Framework for Urbanisation. Among the metropolitan-level spatial strategies, Structure Vision Randstad 2040 (2009) stands out. Randstad is the conurbation constituted by the four largest Dutch cities: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht and their surrounding area. It is famous for its “green heart”, a series of cities and towns surrounding a central area of undeveloped green farmland. Randstad’s current population is 7 million, and it is projected to increase by at least half a million by 2040. It is estimated that at least 500 000 new homes will be needed by 2040. This presents a threat to Randstad’s “green heart”. The aim of the Randstad region is to build “a green, attractive and climate-resilient living environment” and “competitive, sustainable and climate-resilient cities”. It seeks to be a Green-Blue Delta by protecting inhabitants against higher sea levels due to global warming on one side and conserving its valuable “green heart” from rampant urban expansion on the other. In the Structure Vision, the compact city principle is framed in a set of complementary urban development policies that include upgrading transport, natural conservation, mixed-use urban land and more diverse neighbourhoods in the cities. It also intends to transform unused industrial sites into new urban areas with a residential and employment function. To achieve higher density in the existing urban area, Randstad encourages developing high-rise buildings to complement existing lowrise ones.18 The Dutch spatial planning system is a three-tiered system with the state, the provinces and the municipalities being the main planning actors. The relationships between the different tiers are guided by the principle of subsidiarity: ́Only if necessary, decisions should be taken at higher tiers’. Policy coordination is mainly realized by consultation. In the new Spatial Planning Act from 2008, approval of local land use plans by the province is no longer required, the idea being that coordination should rest on mutual consultation. According to the Spatial Planning Act, the state, the provinces and the municipalities all are obliged to prepare indicative plans, called ‘structure visions’ (structuurvisies). Besides spatial issues, structure visions can also concern other issues, like 18 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing, p.262-263 Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 9 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus environmental quality, water management, regional economy etc. The local land use plan (bestemmingsplan) is the most powerful instrument of spatial planning, as it controls changes in land use through a system of permits. It is the only plan that is binding for the citizen (and other actors, like businesspeople).19 There was a real threat of urban sprawl in the Green Heart in the 1960-70s. Spatial planning policies were mainly designed to channel urban growth into a number of designated growth centres (‘concentrated deconcentration’) and to prohibit the growth of small rural settlements. These planning ideas were put into practice successfully in the 1970s and early 1980s. Half a million people moved into the designated growth centres and urban sprawl was stopped. Yet, in the course of the 1980s, spatial planning changed track and the policy of concentrated deconcentration was traded in for the ‘compact city’ policy. This was mainly because of concern about the decay of the old urban centres, which was partly blamed on the development of the satellite towns. Under this new policy of the compact city, in 1991, urban growth was guided into (re)development locations within existing cities (brownfield sites) and towards new greenfield sites directly adjacent to the built-up areas of larger cities in the Randstad Holland. This policy is now being implemented and urban growth both in terms of residences and employment is largely occurring on the urban ring of the Randstad where it was supposed to occur under the compact city policy.20 5.2 Hungary There is no explicit compact city policy in Hungary. However, the compact city approach is implicit in urban planning regulations. It also appears in the National Spatial Plan, which mainly addresses land use and the question of limiting the extension of built-up areas and protecting areas of particular value (landscape, high-quality arable lands, ecological network). The plan also provides an option to set up common planning practices for the main cities and their surrounding areas. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for the plan. For urban planning, the Law on Protection and Formation of Built Environment deals with fundamental requirements, instruments, rights and commitments related to the built environment. It is under the responsibility of Ministry of Interior and covers the regulation of local plans and the efficient use of space and avoidance of waste of resources. The Requirements of Urban Planning and Construction, a government order based on the law, emphasizes intensive and efficient use of areas, the best location of different functions and avoidance of chaotic spatial patterns. Moreover, the National Spatial Development Concept, a parliamentary decree (1998, 2005), addresses the issues of suburbanization and co-operation in agglomerations in the context of the 19 Busck, A., Hidding, M., Kristensen, S., Persson, C. and Præstholm, S. (2008). Managing rurban landscapes in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden: Comparing planning systems and instruments in three different contexts. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 108(2), pp.1-16. 20 Dieleman, F. and Wegener, M. (2004). Compact City and Urban Sprawl. Built Environment, 30(4), pp.308-323. 10 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus sustainable and efficient use of space. The Ministry for National Economy is in charge of this. This is the first legal document in Hungary to set specific goals for certain towns. It addresses polycentricism in relation to Budapest and the other seven regional poles. One of its main goals is to promote the development of a highly competitive Budapest metropolitan area and to create an important hub at the European level by providing a connection to the Balkans. Another aim is to strengthen the development of the hinterland. At the metropolitan level, a clear policy aims at coordinating the development of the Budapest agglomeration based on a compact city approach. The Hungarian Act on Regional Development and Spatial Planning defines the Budapest agglomeration as a functional region of national importance. The Budapest Agglomeration Spatial Plan was then adopted by the national parliament in 2005. The main aspects of the plan are: i) to keep open spaces in built-up areas; ii) to co-ordinate land use and transport infrastructure within the agglomeration; and iii) to protect areas with particular value (landscape, high-quality arable lands, and ecological network). The local governments concerned are legally obligated to follow the plan.21 The adoption of the Act of 1996. XXI. on regional development and physical planning meant a turning point in the field of regional planning, institutions, financial and economic regulation and EUintegration. This legislative provision set its regional developments goals, overall objectives – therefore the partition of competences between the Parliament and the government – in compliance with the regional policy of the European Union. This act forms the basis of the Hungarian spatial policy. However, the act of 1999. XCII. on the modification of the act of 1996. XXI. on regional development and physical planning can be evaluated as a withdrawal in the decentralization efforts in the spatial policy. The significant changes in the membership pattern of the Regional Development Councils are on the way back to the centralization. The National Development Concept (OFK), as an overarching development concept fulfils the role of a country strategy has been elaborated in 2005, parallel to the National Spatial Development Concept. Because of this fact, their main findings are the same: both of them define development poles in Hungary.22 In the 1990s, urban policy-makers in Budapest fully ceded the development formation and investment opportunities to market forces and economic lobbies interested in the development of the city’s outer urban neighbourhood. It should be noted that not only large urban centres but also peri-urban areas attracted foreign direct investments and various developments during the change of the Hungarian political system. Almost all the professional groups concerned and relevant professional documents warned of the foreseeable adverse consequences of the unrestrained 21 OECD, (2012). Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. OECD Publishing, p.248-249. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167865-en. 22 Besze, T. and Lukovics, M. (n.d.). Some aspects of the Hungarian spatial- and settlement development. [online] Available at: http://www2.eco.u-szeged.hu/region_gazdfejl_szcs/pdf/lukovics_miklos/BeszeLukovics_Some_aspects_of_the_Hungarian_Spatial_and_Settlement_Developoment.pdf [Accessed 17 Apr. 2015]. 11 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus territorial expansion. Nevertheless, no regulations with a powerful set of tools were made with the intention of controlling or the ability to influence this ‘spontaneous’ process. This resulted in the unstructured and uncoordinated land use practice that developed in the Budapest agglomeration area (especially in its outskirts) which was characterised by the uncontrolled expansion of urban areas, along with the deterioration of territorial potentials and by the oversupply of potential development areas.23 6. Case studies 6.1 The Netherlands Dutch local authorities are in the process of introducing housing on single-function industrial estates developed after World War II. Local governments are looking for strategies and instruments that will help them to redevelop these sites towards mixed-use areas combining housing and industry. Case studies on the Binckhorst and Plaspoelpolder sites in and around The Hague and the Buiksloterham site in Amsterdam analyses attractiveness of the site as a location for the introduction of housing, the environmental loading caused by combining industry and housing, and municipal strategies for redevelopment of the industrial estates. The possibilities of mixing industry and housing in a given area may be limited not only by planning instruments, but also by environmental regulations. A new approach has been developed in the Netherlands, called the ‘city-and-environment’ approach to prevent mere top-down settings and initiate consultation with all stakeholders in a more decentralized way. The city-and-environment approach has been launched as an experiment between 1999-2003, where local authorities could deviate from national environmental regulations. The first step comprises integration of environmental aspects in spatial plans, and the taking of measures to combat pollution at source, at an early stage. One of the ways local authorities may combat pollution is by granting environmental permits. This allows authorities to encourage users to lower emissions not only by introducing new technologies but also by changing company culture to make employees more environmentally minded. The second step involves exploration of tailor-made solutions to pollution problems if those adopted in step one do not work. Local development strategies are a third aspect of the introduction process that may play a role. Planning instruments based on the idea of the functional city might not work as well in mixed-use developments. Municipalities generally follow a direct development strategy, i.e. they buy the land, lay down the necessary infrastructure and sell plots to development companies or other parties that are responsible for the actual building. The analysed cases show that the introduction of housing alongside industrial and commercial functions forms part of a wider approach to the reorganization of industrial land in a post-industrial era. In this context, housing is seen as an instrument for changing the local urban environment to make it more attractive for other businesses. This represents a shift away from past 23 Szirmai, V. (2012). Urban Sprawl in Europe. Regional Statistics, 2(1), pp.129-148. 12 Town Planning and Housing Department of Cyprus Dutch urban planning practices, where housing was the key issue. This new approach may be seen as a correction to previous single-function development strategies in the direction of a more mixed-use urban fabric. The three cases discussed all involve the introduction of housing at waterfront sites and transformation of quaysides into public space in the interests of creating an attractive living environment. It was found that traditional amenities such as waterfronts can provide ample potential for housing development; that while there may be plenty of room for housing, much of it will be subject to unacceptable environmental hazards; that a cooperative enforcement style is used to mutual adapt the local interpretation of environmental standards to the interests of the mixed-use areas; and that in all cases, local government became strongly involved in the property market in order to internalize the external effects of investments in the area.24 6.2 Hungarian Spatial Decision Support System The greatest challenge for spatial planers is to forecast the complex impacts of plans and to present those to residents and decision makers. Applying the Spatial Decision Support System (SDSS) can help to solve this problem. The case study of Hungary introduces the HUNGARIAN SDSS, adapted from the METRONOMICA software, which was developed by the Research Institute for Knowledge System (RIKS) in the Netherlands (RIKS, 2011). The HUNGARIAN SDSS helps planers and decision makers assessing the complexity and reciprocal relationship of spatial processes, as well as presenting the changes in the environment, spatial use and infrastructure that occur in different scenarios. It also gives a simulation and a summary of the local and regional impacts of the various developments. The programme can handle various input information and planning policy measures on a complex level. To put it simply, it can ”make the future visible” on a map. The integrated approach can already be applied in the early phase of the planning procedure, supporting compromised suggestions and decisions acceptable for all stakeholders. The presentation shows the logic of the model, the calibration and the policy alternative development processes. Also, the assessment of the new zoning regulations that are introduced by the National Spatial Plan and the predicted urban sprawl in Hungary. Applying the spatial decision support system gives an opportunity to present the dynamic spatial change on a map, to run 'what happens if' analyses, to present results, impacts of trends, interventions, and political decisions, thus supporting better-founded decisions. The model also helps the implementation of community planning and can be used as an excellent communication tool in making the planning phase a communication process. Promotes and helps involving communities and creating dialogue. 24 Korthals Altes, W. and Tambach, M. (2008). Municipal strategies for introducing housing on industrial estates as part of compact-city policies in the Netherlands. Cities, 25(4), pp.218-229. 13