Chapter 9 Law and the End of Life We come at last to that part of life

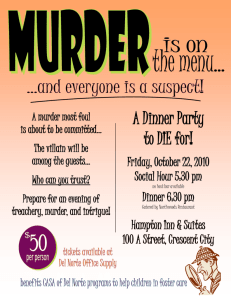

advertisement