Meditation Two

advertisement

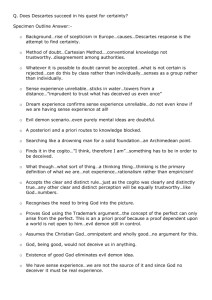

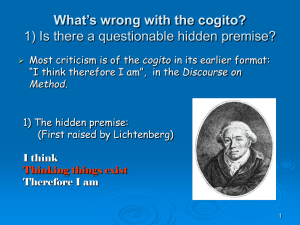

Meditation Two Cogito Ergo Sum Cogito #1 Cogito as Inference □ (Ti→Ei). Not: □ (Ei) Why this might be right Thinking implies the existence of that which thinks It is impossible to conceive that when there is thinking going on, nothing exists. The Cogito simply asserts this necessary connection between the property of existence and the property of thinking in anything capable of thinking. Therefore, one can infer that “X exists” from the truth of the claim “X thinks”, and this is the form of the Cogito argument. Cogito #2 Cogito as Performance The act of thought by which I attempt to doubt my own existence proves that I exist. (Jaako Hintikka) Why this might be right If the Cogito is an inference, it requires independent proof of a buried premise, whereas if it is a performance, it does not, since it is in fact a performance that proves the buried premise true. Hintikka noticed that the truth of “I am thinking” does not by itself establish the necessary truth of “I exist”. As an inference, it seems to presuppose, in addition to the first premise “I exist” another premise: “I cannot think and fail to exist”. What proves that to be true? The attempt to think otherwise. It is this act, this performance that proves one cannot fail to exist when one is thinking. How the Cogito Belief leads to a Criterion for Absolute Truth Ask: What does the Cogito have that all dubitable beliefs lack? ▪ Possible answers: ▪ 1. Clear and distinct ideas ▪ 2. Self-evidence ▪ Descartes’ proposal: if a belief contains, like the Cogito, all and only clear and distinct ideas, and seems self-evidently true to reason when it considers it, then that belief is an instance of knowledge*. Clarity & Distinctness & Self-Evidence What are they? Clarity: obviousness. An idea is obvious if it is in plain view. The idea is not obscured from view. Distinctness: the idea cannot be confused with any other idea. Self-Evidence: A belief that is self-confirming (it expresses what appears to be a necessary truth given the concepts it contains...e.g., “A = A”). The First Use of the Truth Criterion The Proof that “I am a thinking thing” I clearly and distinctly grasp that I am a thing that thinks, and that if I were not to think, I would cease to be what I am. Therefore, I know that I am a thinking thing, and that I exist, and I know this because this is a belief containing all and only clear and distinct ideas, and that is self-evidently true to my reason when I consider it (I cannot think that it is false).* *Note how ‘thinkability’ is doing a lot of work here. The Nature of the Ego Essentially: □ (Ti↔Ei) It appears that here RD is giving the necessary and sufficient conditions for “I”, and these appear to be thinking and existing. This implies that when RD says “Necessarily, I am a thinking thing”, he is asserting both □ (Ti→Ei) and □(Ei→Ti). If so, then □[(−Ti)→(−Ei)] (if I fall asleep, I cease to exist!) RD’s Possible Responses 1. Bite the Bullet 2. Bite the Bullet with Reasons (Karen Quinlan) 3. Deny that this is what he claims follows from “I know that I exist as a thinking thing.” What Jason Thinks About It The relevant part of the Cogito biconditional that produces the apparent problem, i.e., □ (Ei → Ti), should be modified to accurately reflect what RD means in the Cogito. The Cogito assumes the Evil Demon Hypothesis, i.e., the claim that thinking is going on and the Evil Demon is determining its content (within limits we will discuss later in class). The Cogito asks the epistemological question “what do I know given EDH?” It’s scope cannot be the world since the world has been doubted away. Therefore, it is not the ontological question “if I am thinking, does anything exist?” So conditional should be written □(KEi → Ti), which means necessarily, if I know I exist, then I am thinking. This bears no implication that in fact if nothing is thinking, nothing exists. One clue to this interpretation is that the EDH assumes there is thinking going on, yet the usual way of taking the conditional drawn from the Cogito clearly considers a possibility ruled out by EDH...that no thinking is going on. When faced with the proposal that no thinking is occurring, the only appropriate implication is the statement “then I cannot know that I exist”. This is a far cry from the claim that nothing exists. It is even farther from the claim that when you are not thinking, you do not exist. All the cogito supports is the conclusion Has RD Forgotten the Role of Sense Perception in our Discoveries about the Wax? No. We use our senses to get started thinking about the nature of the wax. But when we are finished, we are using all and only ideas that we could not have acquired through sense perception. Because we could not get these ideas from sense perception, the beliefs we form using thtem cannot be based upon sense perception. Why Descartes thinks our ideas of extension cannot come from sense perception: because they have properties that ideas originating in sense perception lack. What Properties Are Those? Consider the idea of a circle. How does it differ from particular circles found in the world, ideas of which you can acquire by seeing or touching them (RD calls these “adventitious ideas”)? ▪ The abstract idea of a circle as it is used in geometry, is a perfect circle (unlike all actual circles we ever have seen or touched). ▪ No true proposition concerning circles could be either proved true or proved false by pointing to some particular circle. ▪ Meno’s paradox of knowledge: You cannot acquire the idea of a circle because any process by which you move from not knowing what it is to knowing what it is requires you to be able to distinguish between what is and what is not a circle, but to be able to do that just is what it is to have the concept of a circle. To acquire the idea of a circle from sense perception requires you to move from not knowing to knowing the idea, and Meno’s Paradox shows this is impossible. Why the nature of the Wax is known by reason, not sense Real properties of the wax, which we can and do know, are infinitary, and sense perception cannot represent that which is infinitary (we cannot “see or touch” infinitely many shapes, for example, yet the wax has the capacity to take infinitely many shapes, and this is one of its essential properties). Comparison of this fact to the chiliagon case: We know that a chiliagon has 1,000 sides, but we cannot see (with our eyes) that a figure with 1,000 sides has 1,000 sides (not without counting them, probably using a magnifying glass). The fact that reason can detect a property that sight cannot present to the mind shows that reason is more acute about extensional properties of objects, and that we must get the idea of a chiliagon from sources other than sense perception (which is incapable of representing a 1,000-sided figure so that it is plainly different from a 999-sided figure). The Plan of the Meditations 1. Use the method of doubt (EDH) to find a criterion for absolute knowledge (by isolating some belief that cannot be doubted) 2. Use that criterion to discover some true beliefs that can be joined in arguments that logically establish conclusions that defeat evil demon skepticism skepticism. How to do That: A. prove God exists as the creator of the world and my mind and all its powers. (Med. III) B. prove that God is not a deceiver (is not an Evil Demon that would mislead me in my belief-forming practices) (Med IV) C. prove that all mathematical truths are instances of absolute knowledge. (Med V) D. prove that these truths describe the real nature of any possible world consisting of bodies in space. (Med V) What Devon Will Try to Prove That Descartes has proved that any possible world must be one consisting of extensional entities (bodies in space) if he properly understands what he has shown in the wax argument. All the arguments given later are redundant, or unnecessary to prove that this is true, and knowable absolutely. If Devon is right: Descartes wasted a lot of time proving the existence of god, god’s nondeceitfulness, the necessary truth of mathematics, and the existence of a world of bodies in space in the meditations following Meditation II.