Rene Descartes 1596 -

advertisement

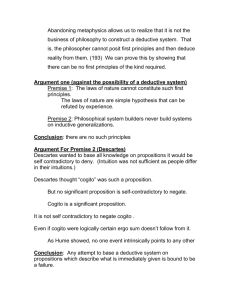

What’s wrong with the cogito? 1) Is there a questionable hidden premise? Most criticism is of the cogito in its earlier format: “I think therefore I am”, in the Discourse on Method. 1) The hidden premise: (First raised by Lichtenberg) I think Thinking things exist Therefore I am 1 What’s wrong with the cogito? 1) Is there a questionable hidden premise? The hidden premise: I think Thinking things exist Therefore I exist This premise is questionable -Does the existence of thoughts necessarily imply a thinker? David Hume argued that we have no right to assume this, as does the anatta (no-self) doctrine of Buddhism. Perhaps Descartes should have said, “There is thinking going on; therefore there are thoughts.” The cogito therefore doesn’t actually establish the existence of a self. “I” is merely a linguistic convenience. It doesn’t actually refer to anything, any more than the “It” in “It is raining.” Descartes strays from his rationalistic agenda here since “thinking things exist” is an a posteriori, empirical observation. 2 What’s wrong with the cogito? 1) Is there a questionable hidden premise? The hidden premise: counter arguments I think Thinking things exist Therefore I exist Ownerless, thinkerless thoughts – pretty weird! The suppressed premise argument assumes that Descartes intended the cogito as a piece of syllogistic (deductive) logic. However, Descartes did not intend the cogito to operate this way. The Meditations should be seen as a course in guided self-discovery and the cogito as a selfauthenticating proposition. According to Cottingham, Descartes expressly made this point to Leibniz at the time. Descartes restates the cogito in the Meditations as “I exist is necessarily true.” to clarify this and overcome the criticism 3 What’s wrong with the cogito? 2) The cogito is circular. I think Therefore I am According to Bertrand Russell the cogito is circular since it assumes what it is setting out to prove. 4 What’s wrong with the cogito? 2) The cogito is circular. Counter argument I think Therefore I am But as with the hidden premise argument, Descartes never intended the cogito to be a deductive argument, and his restatement of the cogito in the Meditations (I am, I exist is necessarily true) overcomes this criticism. 5 What’s wrong with the cogito? 3) The cogito is trivial - It doesn’t tell us anything of significance. Most critics of Descartes are willing to grant him the cogito, but would argue that if this is as far as his argument goes then he has established very little indeed. His task is to overcome scepticism and produce some certainty about the world out there. He claims this is his Archimedian point, his foundational proposition upon which he will build knowledge but, as we shall see, he abandons this as a foundation, and uses arguments for God as his means of overcoming scepticism. 6 What’s wrong with the cogito? 4) Could you exist without a body? Descartes is a dualist - he believes in the existence of a body and a mind. He argues that although he may be deceived by an evil demon into believing he has a body, he must have a mind since he has thoughts. This viewpoint is contrary to modern neuro-science (study of the brain) which takes a monist position – we only have a body. Thoughts exist in the brain nerve cells. Without a brain there can be no thoughts. If you can’t exist without a body then Descartes’ position is seriously undermined. 7 What’s wrong with the cogito? 4) Could you exist without a body? Counter argument Descartes argues that he has more certainty of the existence of the mind than that of the body because, whereas he may be deceived into believing that a physical world (including his body) exists, he, as a mind, must exist to be deceived in the first place. He says that although he can’t establish that he has a body, he can establish that he is a “thinking thing”. 8