IWC training, information management and testing 2009

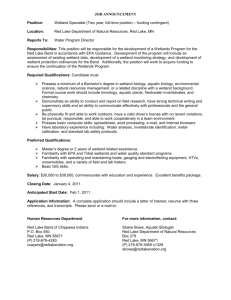

advertisement