LWB433 Professional Responsibility

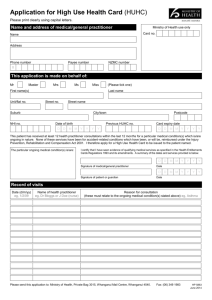

advertisement