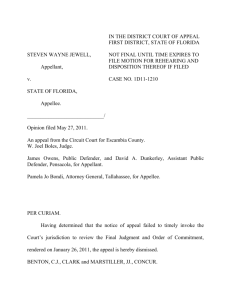

legal notes vol 9-2015

advertisement

LEGAL NOTES VOL 9/2015

Compiled by: Adv M Klein

INDEX1

SOUTH AFRICAN LAW REPORTS AUGUST 2015

SA CRIMINAL LAW REPORTS AUGUST 2015

All SOUTH AFRICAN LAW REPORTS AUGUST 2015

EDITORIAL

Congratulations to Adv Cassim Moosa who is now acting judge in the South

Gauteng High Court!

This made me ponder a bit, when lawyers2 come to the judge’s chambers and

matters are discussed then the rule is that “what is said in chambers stays in

chambers”. The expression was well-marketed for Las Vegas, although a comedian

said "...great to be back here in Vegas....you know how they say 'what happens in

Vegas stays in Vegas'....? Well I have a new saying....if it happens in Vegas, and I

see it....I'm telling EVERYBODY!!"

Unfortunately this has a ring of truth as the judges are more sceptic to divulge certain

information to lawyers, there were two incidents in the newspapers recently where

“what was said in chambers” did not stay in chambers. One was where Judge Cathy

Satchwell made a comment about a litigant and the other one was about Judge

Traverso in the Dewani trial. Also, a judge told me in the tea room that he no longer

entertains lawyers in his chambers. Sad! I always liked the idea of going to a judge’s

chambers as we could at least then be informal and we could sort out issues, i.e.

estimated duration of the trial or whatever. But the opposite could also ring true: I

once told a judge something confidentially which was then repeated by the judge in

court! Perhaps we should agree beforehand “what is now discussed stays in

chambers”….and do not tell client, next it will be in the newspapers.

1

A reminder that these Legal Notes are my summaries of all reported cases as are set out in the Index. In other

words where I refer to the June 2015 SACR , you will find summaries of all the cases in that book. It is for private

use only. It is only an indication as to what was reported, a tool to help you to see if there is a case that you can

use!

2

The term is used as it comprises attorneys and advocates

SOUTH AFRICAN LAW REPORTS AUGUST 2015

ABSA BANK LTD v SNYMAN 2015 (4) SA 329 (SCA)

Magistrates' court — Civil proceedings — Judgments — Superannuation — Occurs

three years after judgment — Execution to be effected within those three years —

Magistrates' Courts Act 32 of 1944, s 63.

Absa Bank Ltd loaned Snyman a sum which it secured with a bond over his home.

When he defaulted on payment Absa obtained default judgment from a magistrates'

court as well as a warrant of execution of the property. Both were obtained on 18

December 2007. Nothing then occurred until 18 December 2010 when the warrant

was reissued. The property was sold in execution on 6 December 2011. Ultimately

Snyman sought the review inter alia of the sale in execution, which the Western

Cape Division of the High Court held was void. Absa appealed this finding to the

Supreme Court of Appeal, where the question was whether a reissue of a warrant of

execution could postpone superannuation of a magistrates' court's judgment.

Held, that a magistrates' court's judgment superannuated after three years (s 63 of

the Magistrates' Courts Act 32 of 1944); and that execution of the judgment had to

take place within the three-year period. Reissue of a warrant within that period would

not postpone superannuation. Here, the sale in execution had taken place more than

three years after the date of judgment, and would on that basis be invalid. (As it

happened, the High Court overlooked the possibility that the sale might have taken

place within three years of the last payment in respect of the judgment — the

alternative date from which superannuation may be calculated. The Supreme Court

of Appeal consequently referred this issue back to the High Court for it to determine.)

Appeal upheld, with referral as aforesaid.

KNIPE AND ANOTHER v NOORDMAN NO AND OTHERS 2015 (4) SA 338 (NCK)

Company — Winding-up — Liquidator — Provisional liquidator — Powers — Power

to sell company assets after final liquidation order granted — Not curbed by

supervening business rescue application — Interdict refused — Companies Act 61 of

1973, s 386(5); Companies Act 71 of 2008, s 131(6).

Business rescue — Liquidation proceedings already initiated — Final liquidation

order granted — Application for business rescue not suspending liquidation —

Provisional liquidators may continue carrying out their functions — May apply to sell

company assets — Companies Act 61 of 1973, s 386(5); Companies Act 71 of 2008,

s 131(6).

Section 386(5) of the old Companies Act 61 of 1973 allows the court to grant a

liquidator 'in a winding-up by the court' leave to 'raise money on the security of the

assets of the company . . . or do any other thing which the court may consider

necessary for winding up the affairs of the company'. Section 131(6) of the new

Companies Act 71 of 2008, which provides that business rescue proceedings will

suspend liquidation proceedings, does not apply where a final liquidation order has

been granted, and will hence not hamstring liquidators who wish to sell company

assets.

DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE v SPEAKER OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND

OTHERS 2015 (4) SA 351 (WCC)

Constitutional law — Legislation — Validity — Powers, Privileges and Immunities of

Parliament and Provincial Legislatures Act 4 of 2000, s 11 — Arrest and removal of

any person creating or joining disturbance during parliamentary, house or committee

sittings — Provision violating Constitution by allowing arrest of members for what

they may say at such sittings — Constitution, ss 58(1) and 71(1).

Parliament — Members — Privileges — Constitutional right to freedom from arrest

for anything said in National Assembly or Council of Provinces or any of their

committees — Violated by provision in s 11 of Powers, Privileges and Immunities of

Parliament and Provincial Legislatures Act 4 of 2000 allowing arrest and removal of

any person for what they may say at such sittings — Constitution, ss 58(1) and

71(1).

Section 11 of the Powers, Privileges and Immunities of Parliament and Provincial

Legislatures Act 4 of 2000 (the Act) allows the Speaker or the Chairperson of the

National Council of Provinces (or a person designated by them) to order 'a staff

member or a member of the security forces' to arrest and remove any person

creating or taking part in a disturbance during parliamentary, house or committee

sittings.

Section 58(1)(a) of the Constitution affords cabinet members, deputy ministers F and

members of the National Assembly (the NA) a right to freedom of speech in the NA

and its committees; and s 58(1)(b) protects such members against inter alia arrest or

imprisonment or damages 'for anything they have said in, produced before or

submitted to the Assembly or any of its committees'. Delegates to the National

Council of Provinces, participating local government representatives and members of

the national executive are afforded the same privileges and powers by s 71 of the

Constitution.

These constitutional privileges are violated by s 11 of the Act to the extent that it

permits a member to be arrested for what he or she may say on the floor of a House.

Because a member may not be arrested under s 11 if the conduct that led to the

arrest is protected under ss 58(1)(b)and 71(1)(b), the most appropriate remedy to

bring s 11 within constitutional bounds would be notional severance — leaving the

text unaltered but limiting the extent of its application by subjecting it to a condition.

The Western Cape Division of the High Court so held in an application challenging

the constitutional validity of s 11 of the Act. Accordingly it declared s 11 of the Act

inconsistent with the Constitution and invalid 'to the extent that it [permitted] a

member to be arrested for conduct that [was] protected by ss 58(1)(b) and

71(1)(b) of the Constitution'. (This declaration was suspended for a period of 12

months in order for Parliament to remedy the defect, and was referred to the

Constitutional Court for confirmation.)

ABSA BANK LTD v COLLIER 2015 (4) SA 364 (WCC)

Act of insolvency — Failure to satisfy judgment debt or indicate sufficient disposable

property to do so — Disposable property — Mortgaged property — Qualifying as

disposable if judgment creditor holds first mortgage bond — Order of special

execution not required — Insolvency Act 24 of 1936, s 8(b).

Under s 8(b) of the Insolvency Act 24 of 1936 a debtor who fails to satisfy a

judgment or point out sufficient 'disposable property' to do so commits an act of

insolvency.

The question here was whether Mr Collier's undivided half-share in immovable

property mortgaged to Absa, the judgment creditor, was disposable property as

intended in s 8(b). The sheriff had rendered a nulla bona return after Mr Collier

allegedly failed to point out sufficient disposable property to satisfy Absa Bank's

judgment against him. Absa, the holder of a first mortgage bond over the property in

question, argued that this was an act of insolvency under s 8(b) and applied for Mr

Collier's sequestration. Mr Collier resisted on the ground that the sheriff's return was

factually incorrect because he had advised the sheriff of his ownership of the

property, the value of which was sufficient to satisfy the judgment Absa had obtained

against him. A single judge of the High Court dismissed the application on the

ground that Absa was, as mortgagee, able to dispose of Mr Collier's half-share in

property without a special execution order and that in the circumstances it had failed

to establish an act of insolvency. In an appeal to a full bench —

Held:

Mortgaged immovable property was disposable only at the instance of the judgment

creditor as first mortgagee regardless of whether it had been declared specially

executable. Since Mr Collier's undivided half-share in the property was 'disposable'

under s 8(b), and since its value was sufficient to satisfy Absa's judgment, no act of

insolvency was committed. Hence a final order of sequestration would not issue.

Appeal dismissed.

SELEKA AND OTHERS v MINISTER OF POLICE AND OTHERS 2015 (4) SA 376

(LP)

Prescription-Extinctive prescription — Interruption — By service of process — Letter

of demand or notice of intention to sue state — Neither constituting service of

'process' affecting running of prescription — Prescription Act 68 of 1969, s 15(1);

Institution of Legal Proceedings against Certain Organs of State Act 40 of 2002, s 3.

The defendants raised a special plea of prescription against actions for damages

instituted by the plaintiffs (for their alleged unlawful arrest, detention and assault by

members of SAPS) on the basis that said actions were instituted I and summons

served more than three years after their respective causes of action had arisen. The

plaintiffs contended that the running of prescription was interrupted as contemplated

in s 15(1) of the Prescription Act 68 of 1969 by the service of their respective letters

of demand and/or notices in terms of s 3 of the Institution of Legal Proceedings

against Certain Organs of State Act 40 of 2002. In issue was whether the letters of

demand and/or notices constituted 'processes' in terms of the aforementioned

provision of the Prescription Act and consequently affected the running of

prescription. The court held that they did not and the claims had accordingly

prescribed

WINDRUSH INTERCONTINENTAL SA AND ANOTHER v UACC BERGSHAV

TANKERS AS THE ASPHALT VENTURE 2015 (4) SA 381 (KZD)

Shipping — Admiralty law — Maritime lien — Seaman's lien for wages — Lien for

wages for crew captured and abducted by pirates — Claim falling within scope of

maritime lien for wages — Lien transferable by cession or assignment — Admiralty

Jurisdiction Regulation Act 105 of 1983, s 1(1)(s).

On 28 September 2010 the Asphalt Venture was hijacked by Somali pirates off the

Kenya coast. Though a ransom was paid and the ship released on 15 April 2011, the

pirates retained seven Indian crew members as hostages. Their employer, Concord

Worldwide Inc, the subcharterer, made payments equivalent to their wages to their

dependent families until October 2011, when it ran into financial difficulties. It was

common cause that the specified periods of employment of the abducted crew had

expired by the time the ship was released.

Bergshav, the respondent in the present case, acting as cessionary of the

wage claims of abducted crew, procured the arrest of Asphalt Venturein Durban in

September 2012. The claims were ceded to Bergshav under a settlement agreement

concluded between Bergshav and the families, which was approved by the Indian

High Court, Mumbai. In its summons in rem in the South African court Bergshav

claimed payment of what it had paid to the families. The present application was for

the release of the Asphalt Venture from its deemed arrest and for the return of the

security furnished. The applicants were Windrush, the original bareboat charterer,

and the ship itself. The question for the court was whether, given the termination of

the employment contracts and the absence of service to the ship after April 2011,

there was a valid claim for unpaid wages capable of supporting a maritime lien.

An ancillary question was whether, even if the claims and the maritime liens existed,

their transfer by cession or assignment was valid, at least without the sanction of the

Mumbai High Court. It was common cause that the abducted crew's employment

contracts were governed by Indian law.

Held: Although the employment of the abducted crew had ended in April

2011, Bergshav was able to show, if only at prima facie level, that Indian law would

recognise their wage claims at all material times to date of repatriation. Whether the

claims were supported by maritime liens enforceable by an action in rem had to be

determined with reference to the lex fori, ie South African law. The issue was in

effect settled by the applicants' concession that the claims were 'maritime claims', for

in South African law the liens would follow the claims. The critical factor, therefore,

was not the time when a claim arose, but whether it fell within the scope of a

maritime lien. It could for present purposes be concluded that crew's prima facie

wage claims did give rise to maritime liens, which were, moreover, by their nature

capable of being transferred by cession or assignment. And since the Mumbai High

Court had, on the applicants' version, indeed sanctioned the assignment, the court

would recognise Bergshav's title. Application dismissed.

STEYN v HASSE AND ANOTHER 2015 (4) SA 405 (WCC)

Cohabitation — Rights — Reciprocal duty of support — Though none arising by

operation of law, it may be regulated by agreement — Universal partnership may

come into being — Requirements — Both parties must contribute or bind themselves

to do so; it must be carried on for joint benefit of both parties; and object must be to

make profit.

Cohabitation generally refers to people who, regardless of their gender, live together

without being validly married to each other. Although cohabitation is a common

phenomenon and widely accepted, cohabitants generally do not have the same

rights as partners in a marriage or civil union. While no reciprocal duty of support

arises by operation of law, this may be regulated by agreement. An express or

implied universal partnership may arise between cohabitants. A universal partnership

exists when parties act like partners in all material respects without explicitly entering

into a partnership agreement. The three essential elements are, first, that each

contributes something to the partnership or binds himself to contribute something to

it; second, that the partnership should be carried on for the joint benefit of the

parties; and, third, that the object should be to make profit.

Mr Hasse, a married German businessman residing chiefly in Germany, was

involved in a romantic relationship with Ms Steyn during a series of interludes he

spent at his house in Somerset West, Western Cape. Steyn ended up living there

rent-free. But when the relationship soured Mr Hasse wanted Steyn out and sent her

an eviction notice. Steyn resisted on the ground that she was living in the house at

Hasse's invitation and, moreover, as his partner. She alleged that he had promised

to provide her with a secure home for 10 years. A magistrates' court, having found

no reciprocal rights and duties of support, held that the withdrawal of Hasse's

consent meant that Steyn's occupation was unlawful and granted an eviction order.

In an appeal to the High Court —

Held

Given the nature of the relationship between the parties, there would have been no

express or tacit universal partnership nor any other legal basis for a finding that there

were reciprocal rights and duties of support. It was moreover highly unlikely that

Hasse would have given Steyn an undertaking to provide her with a home for 10

years, and the averment could be rejected out of hand. Steyn would be given three

months to vacate the premises.

FIRSTRAND BANK LTD v NKATA 2015 (4) SA 417 (SCA)

Credit agreement — Consumer credit agreement — Reinstatement of agreement in

default — Not possible after execution of court order enforcing agreement —

Meaning of 'execution' — Sale in execution at public auction — National Credit Act

34 of 2005, s 129(4)(b).

A consumer brought an application in the High Court for the rescission of a default

judgment and cancellation of the sale in execution of her property after she had

made good her arrears. The court did not rescind the judgment but, relying on s

129(3)(a) of the National Credit Act 34 of 2005 (NCA), declared that the loan

agreements had been reinstated — the default judgment and the writ in execution

had accordingly, by operation of law, ceased to have any force and effect. The

central issue in an appeal by the credit provider to the Supreme Court of Appeal

(SCA) was the meaning of 'execution' in s 129(4)(b) of the NCA. The section

provides that 'a consumer may not re-instate a credit agreement after . . . the

execution of any other court order enforcing that agreement'. The High Court

concluded that 'execution' only took place when the proceeds of the sale

in execution were paid over to the judgment creditor. In contrast the SCA —

Held, that reinstatement could only occur before a sale in execution at a public

auction. The debtor (consumer) had fallen foul of this provision and the order of the

High Court had therefore been wrongly made. Appeal upheld. Since the matter was

decided on the basis of s 129(4)(b), it was not necessary to deal with the High

Court's reasons and findings in respect of s 129(3)(a).

RAHIM AND OTHERS v MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS 2015 (4) SA 433 (SCA)

Immigration — Illegal foreigners — Detention pending deportation — Place of

detention — To be determined by director-general of Home Affairs — Determination

need accord with international best practice and be publicly proclaimed —

Immigration Act 13 of 2002, s 34(1).

Mr Rahim and 14 other foreign nationals sued the Minister of Home Affairs for

damages as a result of what they alleged were their unlawful arrest and detention.

Rahim and the others had applied for asylum but had been unsuccessful and their

appeals had later been refused. Thereafter they had been arrested at the instance of

officials of the Department of Home Affairs, and detained variously at police stations,

prisons and the Lindela holding facility. The arrests and detention had been on the

basis of s 34(1) of the Immigration Act 13 of 2002, which provides that 'an

immigration officer may arrest an illegal foreigner or cause him . . . to be arrested,

and shall . . . deport him . . . and may, pending his . . . deportation, detain him . . .

or H cause him . . . to be detained in a manner and at a place determined by the

director-general . . .'.

Rahim and the others asserted in the High Court that their places of detention had

not been so determined and that this rendered their detention unlawful. The court,

however, found against them, interpreting the Act to provide that prisons and police

stations were places that had been so determined.

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Appeal held that (1) any place used to detain

illegal foreigners pending deportation had to be determined to be a place of

detention by the director-general (the places requiring such determination including

prisons and police stations); (2) that any determination had to accord with

international best practice, which was to the effect that illegal foreigners had to be

detained separately from persons detained for criminal offences; and (3) that no

such determinations had been made here. The court also suggested (the issue not

arising for final decision) that any determination would have to be publicly

proclaimed. Appeal upheld, the detentions found to be unlawful, and the minister

ordered to pay damages.

ORESTISOLVE (PTY) LTD t/a ESSA INVESTMENTS v NDFT INVESTMENT

HOLDINGS (PTY) LTD AND ANOTHER 2015 (4) SA 449 (WCC)

Company — Winding-up — Application — By creditor — Abuse of process — Rule

that court will refuse application as constituting abuse of process where company

bona fide disputing debt on reasonable grounds (Badenhorst rule) — Ambit —

Provisional and final stages — Burden of proof.

Company — Winding-up — Grounds — Inability to pay debts — Discretion of court

to refuse winding-up — When it arises — Competing application for business rescue

— Difference of opinion among creditors on need for liquidation — Company solvent

and misguidedly but genuinely disputed applicant's claim — Companies Act 61 of

1973, s 345(1) read with s 344(h).

NDFT and Essa concluded an agreement under which Essa was to earn a

commission for helping NDFT to obtain an overdraft. When a dispute arose as to

whether Essa had earned its commission, it made a demand for payment under s

345(1)(a) of the (old) Companies Act 61 of 1973 and followed it up with an

application for the provisional liquidation of NDFT. The provisional order was granted

and the second respondent (the Trust) — NDFT's sole shareholder and largest

creditor by virtue of its loan-account claim — given leave to intervene to oppose final

liquidation.

The issues on the return date were —

(i) whether Essa was a creditor of NDFT;

(ii) whether NDFT genuinely (bona fide) disputed its claim on reasonable

grounds;

(iii) whether NDFT was factually or commercially insolvent; and

(iv) whether the court should, if these questions were answered in Essa's favour,

nevertheless refuse to grant a winding-up order.

The Badenhorst rule states that a court will refuse an application for the liquidation of

a company if the company bona fide disputes the applicant's claim on reasonable

grounds. Though its object is to prevent the abuse of the liquidation process for the

enforcement of debts, it is now treated as an independent rule not requiring proof of

actual abuse of process. Hence disputes relating to liability must be distinguished

from disputes about the other requirements for liquidation. Since the court will refuse

the application even where the applicant proves its claim, the Badenhorst rule is

more appropriate in provisional applications, when an onus may be cast on the

company to explain the basis of the claimed dispute (ie its bona fides and

reasonability). At the final stage, however, Plascon-Evans will apply and proof of the

claim will leave little scope for a finding that the debt is nevertheless genuinely

disputed. The requirement of bona fides is satisfied if the company genuinely wishes

to contest the claim and believes it has reasonable prospects of success. Lack of

bona fides will usually go hand-in-hand with an intention to delay, which would in turn

indicate that the company is unable to pay its debts and militate against the exercise

of a discretion in its favour (see below).

While a company's deemed inability — in terms of s 345(1) — to pay its debts does

not give rise to a rebuttable presumption, the court has a residual discretion to deny

the application for liquidation, and the reason the company gives for its refusal to pay

(eg bona fides and reasonability: see (c) below) might result in the court exercising it

in the company's favour. The ambit of the discretion is debated, but whatever its

limits, there must be a valid reason why the liquidation order should be withheld if the

applicant complied with the applicable statutory requirements. Such reasons would

include —

(a) that there are competing applications for liquidation and business rescue;

(b) that there is a difference of opinion among the creditors on the need for

liquidation — in particular, opposition by a major creditor; or

(c) the company is commercially solvent and a presumption of commercial

insolvency arose merely because it misguidedly but genuinely disputed the claim

and therefore refused pay it.

Held: As to (i): Although the facts tended to show that Essa's claim was duly

established, it was, in the light of the findings below, not necessary to decide this

point.

As to (ii): While it was similarly unnecessary to decide this point, any reliance by

NDFT on the Badenhorst rule would have failed, not for lack of bona fides, but

because its grounds for disputing the claim were not reasonable.

As to (iii) and (iv): The clear evidence that NDFT was commercially solvent and the

fact that its largest shareholder opposed liquidation would compel the court to

exercise its discretion against the granting of a final order.

Provisional order accordingly discharged.

ABSA BANK LTD v KEET 2015 (4) SA 474 (SCA)

Prescription — Extinctive prescription — Debt — Claim for rei vindicatio not

constituting debt — Accordingly, not prescribing after three years — Prescription Act

68 of 1969, s 10.

The appellant bank brought an action in the High Court seeking confirmation of its

cancellation of an instalment sale agreement and recovery of the vehicle when the

respondent defaulted on payments. Respondent's special plea of prescription was

upheld on the basis that appellant's claim for repossession of the vehicle was a 'debt'

as contemplated by s 10 of the Prescription Act 68 of 1969 and had thus prescribed

after three years. The main issue on appeal was whether a claim under rei vindicatio

became prescribed after three years by virtue of s 10. The Supreme Court of Appeal,

after reviewing various authorities, held that this view was contrary to the scheme of

the Act. The High Court had accordingly erred in upholding the special plea on this

basis. Appeal upheld.

ELIAS MECHANICOS BUILDING & CIVIL ENGINEERING CONTRACTORS (PTY)

LTD v STEDONE DEVELOPMENTS (PTY) LTD AND OTHERS 2015 (4) SA 485

(KZD)

Business rescue — Moratorium on legal proceedings against company — Leave to

institute proceedings to be obtained before commencement of proceedings and not

as part of relief in main application — Companies Act 71 of 2008, s 133(1)(b).

Applicant company sought an order directing first respondent to produce certain

documentation regarding a joint venture. First and second respondents (the latter

was also a party to the venture) were in business rescue proceedings at the time.

Leave to institute proceedings, as required in terms of s 133(1)(b) of the Companies

Act 71 of 2008, was not obtained prior to commencement but incorporated as part of

the relief in the main application. Counsel for respondents contended that it should

have been obtained before the launch of proceedings. In issue was whether leave

could indeed be sought in the same application in which the substantive relief was

sought. The court held that, on a proper construction of s 133(1)(b), it could not. The

applicant had therefore commenced the present application when it was not entitled

to do so. Such application was not competent and accordingly had to be dismissed.

SARRAHWITZ v MARITZ NO AND ANOTHER 2015 (4) SA 491 (CC)

Housing — Right to housing — Protection of vulnerable purchasers — Seller's

supervening insolvency — Statute failing to give cash purchasers same protection

(right to transfer) as instalment purchasers — Statute amended to provide equal

protection to all vulnerable purchasers in event of insolvency of seller — Alienation of

Land Act 68 of 1981, s 21 and s 22.

In September 2002 Mr Posthumus entered into a contract for the sale of a house to

Ms Sarrahwitz. She paid cash and took occupation in October 2002. But Mr

Posthumus did not transfer the house into her name, and in April 2006 his estate

was sequestrated. The first respondent, who was appointed trustee of Posthumus'

insolvent estate, refused to transfer the house to Ms Sarrahwitz on the ground that it

formed part of the insolvent estate.

Ms Sarrahwitz approached the High Court for an order for transfer but her

application was refused on the ground that the common law and not the Act

regulated the transfer of the house and that the common law supported the trustee's

position. Her subsequent approaches to the full bench of the High Court and the

Supreme Court of Appeal failed for the same reason.

Ms Sarrahwitz's problem was that, as a cash buyer, she did not enjoy the protection

afforded to instalment-sale buyers under s 21 and s 22 of the Alienation of Land Act

68 of 1981. The Act provides that a buyer of residential property who pays the

purchase price in two or more instalments over a period of one year or longer is

entitled to demand transfer if the seller becomes insolvent. In an application for leave

to appeal to the Constitutional Court Ms Sarrahwitz for the first time raised

constitutional principles, arguing that the common law and the Act unconstitutionally

failed to protect vulnerable cash buyers like her.

Majority judgment (per Mogoeng CJ): This case was about the protection of the poor

and vulnerable from homelessness. Given the absence of the exceptional

circumstances required for the development of the common law, the court would

instead approach the matter through a proper interpretation — premised on the

constitutional rights to housing, dignity and equality — of s 21 and s 22 of the

Alienation of Land Act. The purpose of the Act — to protect vulnerable buyers of

residential property — was beneficial, yet its failure to extend its protection to buyers

other than instalment buyers impaired the abovementioned constitutional rights in an

unjustified and irrational manner. Cash buyers and those who paid within a year

should also be protected. Hence the appropriate remedy would be to read into the

Act words that conferred a right on vulnerable buyers who paid cash or who paid in

less than one year to take transfer of the property in the event of the seller's

intervening insolvency, which right would only arise if the buyer were likely to

become homeless if transfer did not take place. In the event the first respondent

would be ordered to transfer the house to Ms Sarrahwitz.

Concurring minority judgment (per Cameron J and Froneman J): The order in the

main judgment would be concurred in with the reservation that it might lead to the

striking-down of beneficial consumer-protection legislation because it failed to protect

everyone equally. This would intrude too far into legislative territory. It was also

difficult to assess the limits of vulnerability that would entitle buyers who paid the full

purchase price to the same protection as instalment buyers. The Constitution,

moreover, did not protect against homelessness in absolute terms. Rather, it

provided that no one could be evicted from his or her home without an order of court

made in consideration of all relevant circumstances. Hence the less intrusive and

more appropriate remedy in the present case would have been to protect Ms

Sarrahwitz's possessory rights by refusing an eviction order.

PRIMEDIA BROADCASTING LTD AND OTHERS v SPEAKER OF THE

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND OTHERS 2015 (4) SA 525 (WCC)

Parliament — Proceedings — Broadcasting — Limitations on broadcasting of

unparliamentary conduct and grave disorder — Jamming of electronic signals during

turmoil in Parliament — Invocation of parliamentary rules and policy —

Constitutionality of such measures — Whether limitations reasonable and justifiable

in open and democratic society — Constitution, ss 57(1), 59(1)(b), 70(1) and

72(1)(b).

Sections 57(1) and 70(1) of the Constitution provide that the National Assembly (the

NA) and the National Council of Provinces (the NCOP) may determine and control

their internal arrangements, proceedings and procedures, and make rules and

orders concerning their business. Sections 59(1)(b)(i) and 72(1)(b)(i) of the

Constitution provide that the NA and the NCOP must conduct their business in an

open manner and hold their sittings in public, but that they may regulate public

access (including the media) if it 'is reasonable and justifiable to do so in an open

and democratic society'.

Parliament's standing rules relating to the broadcasting of parliamentary proceedings

(the Rules) provide that during incidents of disorder or unparliamentarily conduct the

camera must focus on the occupant of the chair, ie the Speaker of Parliament or the

Chairman of the NCOP. This measure is repeated for incidents of 'grave disorder' in

Parliament's later Policy on Filming and Broadcasting (the Policy), but '(o)ccasional

wide-angle shots of the chamber are acceptable' in the case of unparliamentarily

behaviour.

The applicants challenged these measures on the basis that they were not

reasonable and justifiable limitations of the open and public nature of parliamentary

sittings as contemplated in ss 59(1)(b) and 72(1)(b) of the Constitution; alternatively,

that the Policy and the Rules as a whole were irrational for lack of public consultation

before they were adopted, and were therefore unconstitutional.

An order was also sought declaring the continued use of a device jamming electronic

signals in Parliament unconstitutional and therefore unlawful. This arose from a

'jamming incident' which had prevented cellphone use during the first part of the

same joint sitting of the NA and the NCOP in which the impugned measures where

invoked to limit coverage of the proceedings when it was deemed to have

descended into 'grave disorder'.

The full bench (by a majority) rejected the alternative ground on the basis that it was

sufficient that the measures were devised for Parliament's functioning by Parliament

itself, on a fully cross-party deliberative basis. It also rejected the declaratory relief

sought in relation to the jamming incident as 'serving no purpose whatsoever'.

As to the main issue — the reasonableness of the impugned measures —

Held

The public's right to know what was happening in Parliament was not absolute. The

question was whether these limitations were reasonable — regard being had to what

they sought to achieve and their context. The measures protected the dignity of

Parliament by tempering the especially strong impact that visuals of disorderly

conduct, if broadcast to the world, would have. They were designed to discourage

disorderliness and unparliamentarily behaviour; indeed they were essential for its

ordered operation. Thus, regard being had to all relevant factors, the measures

under discussion in the instant matter are 'reasonable measures' employed

to regulate public access, including access of the media, to Parliament.

Conduct obstructing or disputing Parliament's proceedings, or unreasonably

impairing Parliament's ability to conduct its business in an orderly and regular

manner acceptable in a democratic society, was (in any event) not legitimate

parliamentary business, and accordingly there was no obligation on Parliament to

broadcast such conduct.

Unreasonableness must be a high standard, particularly when an independent

constitutional institution had, through its own internal cross-party processes, drawing

on the experience of its own members and with regard to the practice under other

constitutional democracies elsewhere, done exactly what ss 59(1)(b) and 72(1)(b) of

the Constitution contemplated.

Parliament was constitutionally entitled to ensure its functioning and to protect its

own dignity. The challenged measures were reasonable, justifiable and

proportionate, striking a balance between the right to be informed about Parliament

and the duty to maintain the dignity of parliament.

ZA v SMITH AND ANOTHER 2015 (4) SA 574 (SCA)

Delict — Elements — Unlawfulness or wrongfulness — Liability for omission —

Failure to warn paying visitor to nature reserve of danger of slipping on

ice concealed by snow and sliding over edge of gorge.

In this matter Federica Za sued the owner of a farm (Smith) and a corporation that

carried on the business of a private nature reserve on the farm, for loss of support as

a result of the death of her husband Pieralberto. Za alleged that their omission had

resulted in his death. The background was that the corporation allowed members of

the public to use certain amenities on the farm, including a four-wheel drive track, for

a fee. On the winter day in question Pieralberto had paid the fee and driven his fourwheel drive to the terminal point of the track, which was a parking area at the top of a

mountain. There he had alighted and walked across the apparently snow-covered

ground to look into the gorge that was close by. Near to, but not at the edge of the

gorge, Pieralberto had slipped on ice concealed by the snow, had slid over the edge

and fallen to his death.

Federica's action in delict was based on Smith and the corporation's failure to take

steps to avoid the incident. (Those steps would be: (i) briefing members of the public

— inter alia — on the danger of slipping on ice concealed by snow and sliding over

the edge of the gorge ('the danger'); (ii) moving the parking area lower down, to

cause visitors to have to walk some distance on the snow toward the outlook over

the gorge, in order to familiarise them with the surface; (iii) fencing the parking area,

leaving an opening through which the visitors would have to pass, and at which

warning signs would be placed; (iv) warning, by means of those signs, of the danger;

(v) and marking out with poles the edge of the safe area and the unsafe area

beyond.)

Za was unsuccessful in the High Court and appealed to the Supreme Court of

Appeal. In issue there was the following.

(1) Whether the omission was wrongful (ie whether it was reasonable to impose

liability for the omission).

Held, that it was. This on the basis of the following considerations:

(a) the law's policy, as reflected in the common-law duty of a person in control

of a property containing a danger, to render the property safe for visitors;

(b) that Smith and the corporation were indeed in control of a property

containing a danger to visitors; and

(c) that the corporation and Smith allowed the public onto the property to, for a

fee, use a four-wheel drive route that led directly to the danger.

(2) Whether Smith and the corporation had been negligent. Specifically, whether

a reasonable person in their position would have taken steps to warn and protect a

person in the position of Pieralberto against the danger. (They contended that a

reasonable person would not have done so, because the danger would have been

clear to a person in Pieralberto's position.)

Held, that a reasonable person would have taken such steps. This because the

danger would not have been clear, and the proposed remedial steps (listed above)

would have been effective, affordable and sustainable.

(3) Whether the omission to take the steps outlined above was the cause of the

harm. (Smith and the corporation argued that Pieralberto had in fact been aware of

the danger, but had nonetheless proceeded to walk to the edge, and thus that even if

they had taken any of the proposed measures, the incident would still have

occurred.)

Held, that Pieralberto had not been aware of the danger and that the warning

measures would probably have been effective, and consequently that the omission

had been the cause of the incident.

Appeal upheld.

MBATHA AND OTHERS v JOHANNESBURG CITY AND OTHERS 2015 (4) SA

591 (GJ)

Local authority — Housing — Temporary emergency accommodation — Municipality

offering flood-affected residents of informal settlement temporary shelter in

community hall — Facilities inadequate in circumstances — Temporary

accommodation to be provided in terms of emergency housing programme

contained in National Housing Code — Housing Act 107 of 1997, s 9(1).

The impoverished residents (applicants) of an informal settlement on a flood- line —

the area was earmarked for upgrading — had been severely affected by excessive

flooding. The City of Johannesburg (the City) had offered to provide temporary

shelter in a local community hall. Dissatisfied, the applicants brought an urgent

application seeking, inter alia, immediate relocation to a site identified by the City in

terms of its emergency housing programme contained in the National Housing Code

2009 (NHC). The City was sceptical of the need for emergency flood relief and

resisted the application, suggesting that the main goal was permanent relocation.

Held, that, a proper scrutiny and reading of the provisions of the NHC — clause

2.3.1 plainly refers to 'emergency situations of exceptional housing' — was in favour

of the applicants. In addition, the City was obliged, in terms of s 9(1) of the Housing

Act 107 of 1997, to ensure that conditions not conducive to the health and safety of

inhabitants, like the applicants, were I prevented or removed. To provide the

applicants with temporary emergency accommodation at the community hall until the

development was completed would create issues relating to their constitutional

rights. This was untenable. In terms of both the emergency housing programme and

Disaster Management Act government institutions were anyway supposed to have

the appropriate mechanisms in place. The application was accordingly successful.

GB MINING AND EXPLORATION SA (PTY) LTD v COMMISSIONER, SOUTH

AFRICAN REVENUE SERVICE 2015 (4) SA 605 (SCA)

Revenue — Assessment to tax — Objection — Whether competent if assessment

based on incorrect information supplied by taxpayer — Burden of proof when

objecting against such assessment — Income Tax Act 58 of 1992, s 81(1).

Section 81(1) of the Income Tax Act 58 of 1992 (the Act) provided that any taxpayer

'aggrieved by any assessment' may object to such assessment in the prescribed

manner. Here the taxpayer had raised objections in terms of this section to revised

assessments over four tax years, contending that they were based on incorrect

information that the taxpayer itself had supplied to the Commissioner of the South

African Revenue Service (the Commissioner) in its tax returns. The objections

having been disallowed by the Commissioner — one in full and the others partially —

the taxpayer unsuccessfully appealed to the tax court. In the taxpayer's further

appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal, the issues were —

(1) whether, given that s 79(A) of the Act specifically dealt with reduction of

assessments based on incorrect information provided in the taxpayer's return, it was

permissible for the taxpayer to object in terms of s 81(1) rather than relying on s

79(A); and

(2) whether, given that s 81 of the Act placed the burden of proof on the taxpayer,

the onus of satisfying the Commissioner that the information supplied by the

taxpayer was incorrect (and that the reduction was therefore justified) had been

discharged.

Held as to (1):

A taxpayer who had been the cause of an incorrect assessment by the

Commissioner could, as an alternative to relying on s 79A, claim to be 'aggrieved'

thereby and object to the assessment in terms of s 81. This was because a taxpayer

whose taxable income had been determined on an erroneous basis was always

'aggrieved' even if the source of error was entirely attributable to him; and also

because the powers of the Commissioner under s 79A could be exercised

'notwithstanding the fact that no objection [had] been made', suggesting that an

alternative route for the taxpayer to follow was by way of objection and, if necessary,

appeal.

Held as to (2):

The onus of satisfying the Commissioner that the information furnished was incorrect

and that a reduction in the assessment was justified was on the taxpayer. In order to

discharge this onus, additional evidence would have to be placed before the

Commissioner, the nature of which would depend upon the facts of each case and

particularly the nature of the erroneous information supplied to the Commissioner.

Such evidence would have to explain the precise nature and extent of the incorrect

information and how it was included, and all relevant supporting documentation to

verify the correct information would have to be submitted. So where the contested

determinations were based upon incorrect information supplied to the Commissioner

by the taxpayer — whether in the form of balance sheets and accounts or otherwise

— the taxpayer must show that it provided credible and reliable evidence to explain

the error and substantiate what it maintained was the true position.

This the appellant taxpayer had failed to do, and the appeal was accordingly

dismissed insofar as it related to the Commissioner's determinations based on

incorrect information furnished by the taxpayer.

ONE STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES (PTY) LTD v NEFFENSAAN

ONTWIKKELINGS (PTY) LTD AND ANOTHER 2015 (4) SA 623 (WCC)

Company — Contracts — Authority — Internal formalities — Presumption of

compliance (Turquand rule) — Codification of rule in Act — Provision to be

construed consistently with conventional scope of Turquand rule — Companies Act

71 of 2008, s 20(7).

Company — Contracts — Authority — Interplay between actual authority, ostensible

authority, constructive notice of company articles to third parties, and Turquand rule

— Turquand coming to outsider's aid, subject to implications of constructive

knowledge of articles, once he makes out case for ostensible authority —

Companies Act 71 of 2008, s 20(7) not changing common law on ostensible

authority I

In an application for the provisional liquidation of Neffensaan the issue was whether

the applicant, OSF, had locus standi as creditor by virtue of claims under three

agreements it had concluded with Neffensaan. Since OSF was unable to show on

the affidavits that the directors who signed the agreements on Neffensaan's behalf,

M and C, had actual authority to bind Neffensaan, the question became whether

Neffensaan was nevertheless bound by ostensible authority and the Turquand rule,

or by s 20(7) of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 (the Act). OSF stated that it had acted

in good faith and under the impression that M and C were, as directors of

Neffensaan, duly authorised to conclude the agreements, and for the rest it relied on

the Turquand rule. (The application was opposed by CRL, an intervening creditor.)

The Turquand rule (also known as the indoor-management rule) provides that an

outsider transacting with a company may assume that its officers have the powers

ordinarily associated with their positions, thus relieving him from having to

investigate whether the company's acts of internal management were regular. The

Turquand rule has an ameliorative effect, from the perspective of the outsider, on the

rule of constructive notice, under which knowledge of the contents of the company's

articles is imputed to him. The rule of constructive notice was abolished by s 19(4) of

the Act.

Section 20(7) of the Act provides that an outsider may presume that the company

has complied with any 'formal and procedural requirements' unless he knew or ought

to have known of a failure to do so.

Since the first of the agreements — a suretyship agreement — was concluded

before the coming into force of the Act, and the others — two loan agreements —

thereafter, the court had to consider the applicable law under both regimes.

The law before the Act

The Turquand rule would come to an outsider's aid only once he had, subject to the

implications of his constructive knowledge of the company's articles, made out a

case for actual or ostensible authority.

The law after the Act

Section 20(7) was not intended to change the law governing the circumstances in

which a company would be bound on the basis of ostensible authority. Hence the

expression 'formal and procedural requirements' must be construed consistently with

the conventional scope of Turquand. But the abolition of constructive notice means

that a company may now be so bound even if the official went beyond the potential

scope of his authority under the articles.

Application of the law to the present case

Authority to conclude the suretyship agreement: The absence of evidence regarding

the contents of Neffensaan's articles precluded OSF's reliance on the Turquand rule.

This left only ostensible authority, without the refinements of constructive knowledge

and the Turquand rule being brought to the enquiry. But OSF was, by virtue of its

denial of actual knowledge of Neffensaan's articles, precluded from relying on the

ostensible authority of M or C to bind Neffensaan to the suretyship agreement. OSF

was, moreover, unable to point to conduct of Neffensaan by which it held out that M

or C was authorised to conclude this sort of agreement on its behalf. In the result

OSF's reliance on the suretyship agreement would fail. Authority to conclude the

loan agreements: Given the overlap between the Turquand rule and s 20(7), the

absence of evidence regarding the contents of Neffensaan's articles similarly

precluded a reliance on s 20(7). As was required under the former regime, the

outsider had to establish that he was dealing with someone who had actual or

ostensible authority to bind the company, for only in those circumstances would he

be able to say that he was dealing with the 'company' as intended in s 20(7). Given

the lack of ostensible authority on the part of M and C, OSF's reliance on the loan

agreements would fail as well. Application for provisional liquidation accordingly

dismissed.

SACR AUGUST 2015

DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS, WESTERN CAPE v PARKER 2015 (2)

SACR 109 (SCA)

Theft — What constitutes — Misappropriation of VAT — Whether misappropriation

by VAT vendor of VAT collected on behalf of Sars sustaining charge of common-law

theft — Value – Added Tax Act 89 of 1991, ss 28(1)(b) and 58.

A VAT vendor who misappropriates an amount of VAT which it collected on behalf of

the South African Revenue Service (Sars) cannot be charged with the common-law

crime of theft.This is because the Value-Added Tax Act 89 of 1991 is a scheme with

its own directives, processes and penalties, and does not confer on the vendor the

status of a trustee or a tax-collecting agent of Sars — the basis advanced for such

misappropriation constituting theft. Instead, the Act creates a sui generis debtor –

creditor relationship which entitles Sars to sue a non-paying vendor for payment

and/or to have such vendor charged with s 58 offences which, significantly, does not

include common-law theft.

S v COCK;S v MANUEL 2015 (2) SACR 115 (ECG)

Rape — Sentence — Life imprisonment — Minimum sentence in terms of Criminal

Law Amendment Act 105 of 1997 — Gang rape — Different treatment accorded to

first participant to be convicted for participation in gang rape to that of subsequent

participants convicted — Court pointing out anomaly but holding that it was bound by

Supreme Court of Appeal authority — Sentence of life imprisonment imposed under

prescribed minimum sentence legislation accordingly set aside but, in exercise of

court's common-law discretion, new sentence of life imprisonment imposed.

In two separate appeals to the full division against sentences of life imprisonment

imposed upon the two appellants arising from their having raped the complainant in

the execution or furtherance of a common purpose, the court felt obliged to comment

on the anomalous situation brought about by the judgment of the Supreme Court of

Appeal in the matter of S v Mahlase [2011] ZASCA 191. The anomaly that arose in

the present situation was that in terms of this decision the appellant in

the Cock matter, being the first accused to be convicted and sentenced, was liable to

a minimum prescribed sentence of only ten years' imprisonment, whereas any other

accused who was thereafter convicted as having been part of the gang which raped

the complainant (the appellant in the Manuel matter) would be liable to the

prescribed minimum sentence of life imprisonment, it now having been established

that the complainant had indeed been raped more than once, ie by two men. The

court held that it was bound by this decision and that the sentence of life

imprisonment imposed on the appellant in the Cock matter had to be set aside.

The court held, however, that in the exercise of its common-law jurisdiction it was

free to impose any sentence in excess of the prescribed minimum sentence of ten

years' imprisonment and, having regard to all the circumstances, including the fact

that the complainant was gang raped, the only appropriate sentence was that of life

imprisonment.

In respect of the appellant in the Manuel matter the court held that there were no

substantial or compelling circumstances which would justify the imposition of a lesser

sentence than life imprisonment and the appeal in respect of this appellant was

accordingly dismissed. As a new sentence of life imprisonment was imposed on the

appellant in the Cock matter, that sentence had to be backdated to the date of the

imposition of the original sentence.

S v MOTSEPE 2015 (2) SACR 125 (GP)

Defamation — Elements of offence — Unlawful and intentional publication of matter

concerning another which tended to injure his or her reputation — Journalist

appealing conviction of defamation — Published story defamatory of magistrate —

Based on incorrect facts which journalist believed to be true — Lacking intention —

Appeal succeeding.

Defamation — Whether offence consonant with Constitution — — Various amici

seeking to have common-law crime of defamation declared unconstitutional in regard

to media — Not succeeding — Whilst existence of criminal defamation undoubtedly

limited right to freedom of expression, such limitation was reasonable and justifiable

in open and democratic society and was consistent with criteria laid down in s 36 of

Constitution.

The appellant appealed against his conviction in a magistrates' court for criminal

defamation. The circumstances of the conviction were that the appellant, a journalist,

had written an article for a major newspaper dealing with two sentences imposed by

a white magistrate, one on a black man and the other on a white woman, which

suggested that the magistrate was biased. It was common cause that the articles

were published and, on a proper reading, it clearly injured the reputation of the

magistrate, and only intention and unlawfulness were in issue. The evidence was to

the effect that the appellant had relied on information received from an attorney and

that he had not verified the information. On appeal the court held that, on the

evidence, the appellant was clearly negligent in not taking further measures to

ensure that the information he received was correct. The court held, further, that the

court a quo was correct in holding that the appellant had acted hastily and had

thrown all caution to the wind and in this regard the finding that he had acted

recklessly was correct. Recklessness, however, did not equate to intention.

Held, further, that from the evidence it appeared that the appellant had relied on the

truth of the statement and deemed it in the public interest to publish the facts. Once

a person thought that the published words were covered by one of the recognised

defences to a claim for defamation, such person lacked the necessary intention

required for a conviction on criminal defamation. In the premises the state had failed

to prove intentional publication beyond a reasonable doubt and the conviction could

not stand.

Fourteen institutions applied to intervene in the appeal as amici curiae in the

interests of the media and their concern regarding the effect of criminal defamation

laws on the freedom of the media and the constitutionality of criminal defamation

laws. They contended that the civil remedy for defamation provided adequate means

to deter and prevent defamation by the media. They relied on a number of

international instruments and international case law to support their argument in

favour of the repeal of criminal defamation laws against the media. They contended

that the common-law crime of defamation was not consistent with the

Constitution and amounted to an unjustifiable limitation on the right to freedom of the

media. They requested that the court should develop the common law to limit the

crime to the publication of defamatory statements by persons who were not

members of the media.

Held, that there could be no doubt that the right to freedom of the media was of

critical importance and the media stood in a distinct position relative to the general

right to freedom of expression.

Held, further, that the request that the criminal defamation law be declared

unconstitutional undermined the Constitution and the Promotion of Equality and

Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000. Almost all of the international

instruments and international case law referred to by the amici in support of their

argument involved the condemnation of extreme situations of governmental abuse of

journalists. These examples did not find application in South Africa where journalists

and citizens enjoyed the benefit of the law and the Constitution.

Held, further, that freedom of expression did not have a superior status to other

rights under the Constitution.

Held, further, that a criminal sanction was indeed a more drastic remedy than the

civil remedy but that disparity was counterbalanced by the fact that the requirements

for succeeding in a criminal defamation matter were much more onerous than in a

civil matter and these onerous requirements in the case of criminal defamation would

probably be the reason for the paucity of prosecutions for defamation compared to

civil defamation actions.

Held, further, that prosecution of media journalists who committed a crime of

defamation was not inconsistent with the Constitution. In exercising their rights under

s 16 of the Constitution, the media should also guard against rights of others, as

freedom of expression was not unlimited and had to be construed in the context of

other rights, such as the right to human dignity.

Held, further, that the amici failed to make out a case for the decriminalisation of

defamation. Even though the defamation crime undoubtedly limited the right to

freedom of expression, such limitation was reasonable and justifiable in an open and

democratic society and was consistent with the criteria laid down in s 36 of the

Constitution. The appeal was accordingly upheld and it was declared that the

common-law crime of criminal defamation as pertained to the media was consistent

with the Constitution.

LAPANE v MINISTER OF POLICE AND ANOTHER 2015 (2) SACR 138 (LT)

Arrest — Without warrant — Further detention of accused — Constitutional duty on

police officers and public prosecutors handling case to ascertain reasons for further

detention — Such reasons or lack thereof to be placed before court —

Housebreaking implements found 'near' plaintiff not justifiable reason — Acted mala

fide — First and second defendants liable to plaintiff.

Prosecution — Prosecutor — Powers and duties of — Prosecutor unable to assist

court to assess whether prosecution and detention were justified in circumstances —

Housebreaking implements found 'near' plaintiff not justifiable reason to refuse bail

— Aware that without proof of presence of implements conduct would amount to

mala fides — Prosecutors did not apply their minds, rubber-stamped requests of first

defendant — Acted mala fide — First and second defendants liable to plaintiff.

The plaintiff instituted action against the first defendant, the Minister of Police, and

the second defendant, the Director of Public Prosecutions, for damages arising out

of an unlawful arrest, detention and prosecution. He was detained for 2 years and 13

days without being granted bail before the charges were withdrawn against him

without going to trial. The plaintiff testified that he was on his way home from a

nearby tavern when he was arrested. He alleged that he was denied any information

as to the reason for his arrest and that he was subsequently tortured and questioned

about a housebreaking and robbery. He was denied bail based on the submissions

made by the investigating officer and the prosecutor that he had been found in the

company of three other men and that housebreaking instruments were found near

him. The other men were released on bail or on a warning but he was continually

denied bail. It appeared that on the night in question an informer had tipped off the

police that another robbery was to be committed that night in the area where there

had recently been a spate of robberies. Despite the fact that the plaintiff had an alibi

that was very easy to check, the police relied entirely on the information of an

informer. The arresting officer could not say how close the alleged housebreaking

instruments were to the plaintiff and his fingerprints were not found on them.

The control prosecutor who took the decision to oppose bail relied entirely on the

contents of the docket in this regard and to inform the decision that the plaintiff

should be charged. She was unable to answer or explain why the plaintiff was

treated differently — at the time of his bail application — from the others who were

given bail or allowed to go on a warning.

Held, that the prosecutor's reliance on the alleged presence of

housebreaking implements near the plaintiff was not a justifiable reason to prosecute

him and refuse bail. This was not simply an error of judgment. Her conduct and

those of the prosecutors who took over were activated by mala fides, as they must

have known that without the proof of the presence of housebreaking implements, as

well as a failure to follow up on the plaintiff's explanation about his presence at the

tavern, their conduct would amount to mala fides.

Held, further, that the prosecutor and the relevant prosecutors seeking the

many postponements were responsible for the unfortunate and lengthy incarceration

of the plaintiff. Not one of the prosecutors had applied their minds to the case facing

the plaintiff but simply rubber-stamped the request by the police. In the

circumstances, the employees of the first and second defendants did not exercise

their powers in a bona fide manner and the first defendant was liable to the plaintiff

for the unlawful arrest and detention, while the second defendant was liable for the

prosecution and continued withholding of bail.

HO t/a BETXCHANGE AND ANOTHER v MINISTER OF POLICE AND OTHERS

2015 (2) SACR 147 (GJ)

Search and seizure — Search warrant — Warrant issued in terms of

Counterfeit Goods Act 37 of 1997 — Founding papers — Application for copies of

documents or statement that led to warrant being issued — Person entitled to such

information as part of judicial oversight of state's intrusion into individual's privacy —

Form of such application not necessarily by way of rule 53 review but any procedure

that was orderly and conducive to expeditious litigation acceptable — Relief justified

in order to take steps to protect dissemination of private information to prejudice of

applicant.

The two applicants were related companies whose businesses had been

subjected to a search by the South African Police Service in terms of a search

warrant that had been issued by a magistrate under the Counterfeit Goods Act 37 of

1997. The applicants operated a bookmaking business at two premises which were

licensed to sell alcohol which the patrons apparently consumed while betting and

watching horse racing screened by MNet on television sets via satellite signals fed

through a decoder. The complaint which led to the issue of the search warrant had

been initiated by the twelfth respondent, Tellytrack, which filmed the horse races and

streamed the images to MNet. Tellytrack had recently changed its conditions of

supply to MNet by confining its open viewing to the home market and requiring

businesses to pay for a separate licence to screen the races to their customers in

pubs and clubs. This change related to a dispute between the applicants and

Tellytrack which was being litigated separately. The applicants applied in the present

proceedings, pending the application to set aside the search warrants, to order the

respondents to deliver a copy of the complaint affidavits or statements used in

support of the applications for the warrants of search and seizure. The applicants

had requested that the affidavits or statements be supplied to them but the

respondents had refused to supply them and contended that the applicants'

approach to the court was the wrong way to compel disclosure, and until they were

compelled in the appropriate form they would refuse to disclose the documents.

They argued that the applicants would be entitled to the documents upon the

bringing of a review application in terms of rule 53 of the Uniform Rules to set aside

the magistrate's decision to issue the warrants.

Held, that if, as it seemed to be conceded, the applicants had a right to

the documents and the only real dispute was the procedure by which they had to be

disgorged, it followed that unless the procedure adopted by the applicants could be

faulted as being inimical to orderly litigation, no reason existed to proscribe it. It

seemed that a rule 53 approach was appropriate when the decision-maker had to go

to the trouble to compose a 'record', but a rule 6 application was appropriate when

the documents sought were unequivocally described and were already in existence,

on the shelf, so to speak, awaiting only the photocopier's caress, to be produced and

handed over as in the instant case.

Held, further, that the very purpose of requiring judicial oversight over the issue of

the warrant to enter, search and seize was to protect a person's right to privacy and

to subject to judicial scrutiny and oversight a belief by the police, however bona fide,

that they really had a need to invade a person's privacy and that they had shown a

cogent basis for a lawful invasion to be authorised, because not every alleged crime

justified a search warrant to procure evidence. Such considerations pointed towards

any person having a right of access to the founding papers in respect of a search

warrant, as part and parcel of the broader right to privacy and freedom from arbitrary

state action, values which permeate the Constitution.

Held, accordingly, in any exercise to assert the right to privacy and freedom from

arbitrary power, where a procedure that was orderly and conducive to expeditious

litigation was selected, it was improper to resist disclosure. The insistence on the use

of a rule 53 procedure was inappropriate, and the idea of awaiting a prosecution

misdirected, and the relief had to be granted. The court ordered accordingly.

S v JR AND ANOTHER 2015 (2) SACR 162 (GP)

Child — Offences against — Deliberate neglect of a child — Ambit of section

in respect of persons who may commit offence — Legislature having cast net wide

and section covers any person who may even temporarily or partially and voluntarily

be caring for the child — Children's Act 38 of 2005, s 305(3)(a).

Child — Offences against — Deliberate neglect of a child — Sentence — Biological

mother of child treated more severely than actual abuser as she F had greater

responsibility to child — Children's Act 38 of 2005, s 305(3)(a).

Rape — Sentence — Rape of minor — Mother convicted as accessory after fact —

Sentenced to seven years' imprisonment on this count — Mother's boyfriend,

convicted of having raped child, sentenced to life imprisonment.

The two appellants were convicted in a regional magistrates' court of assault with

intent to do grievous bodily harm (count 1); deliberately neglecting to attend to the

injuries of the 13-month-old child (D) in contravention of s 305(3)(a) of the Children's

Act 38 of 2005 (count 2); and a contravention of s 3 of the Criminal Law (Sexual

Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007 by raping (count 3). The

first appellant, the biological mother of the child, was sentenced to ten years'

imprisonment in respect of count 1; eight years' imprisonment for count 2; and seven

years' imprisonment as an accessory to rape in respect of count 3. Five years of

the sentence for count 2 was ordered to run concurrently with the sentence on count

1. The second appellant, the first appellant's boyfriend, was sentenced to 10 years'

imprisonment for the first count, five years' imprisonment for count 2; and to life

imprisonment in respect of count 3. After considering the evidence the court upheld

the findings of the court a quo that both appellants were guilty on all three counts. In

coming to this conclusion the court had to inter alia consider a submission by the

second appellant that he was not in any way responsible for D and that therefore the

conviction brought out against him on count 2 was wrong in law as s 305(3)(a) did

not apply to him. As regards sentence, the first appellant contended that the

magistrate had erred in not taking counts 1 and 2 together for the purpose of

sentence as the offence of abuse stemmed directly from the assault. She also

submitted that the disparity between the sentence of eight years' imprisonment

imposed on her for count 2, as compared to the sentence of five years' imprisonment

imposed on the second appellant, was unfair. She furthermore contended that the

sentence of seven years' imprisonment imposed on her for being an accessory to

rape was excessive. It was contended for the second appellant, with respect to the

appeals against the sentences imposed, that there was no evidence that the child

had suffered any psychological trauma; that the appellant showed remorse; and that

he had limited intellectual capacity; and that these factors cumulatively justified a

sentence less than the minimum sentence of life imprisonment.

Held, as to the application of s 305(3)(a) to the second appellant, that the provisions

of the section were clear and that even a person who voluntarily cared for a child,

whether temporarily or partially, may be guilty of the offence of deliberately

neglecting a child. It was clear that the legislature had sought to spread the net cast

by the subsection as widely as possible in relation to who was deemed to be a

caregiver. It seemed that even if a person were a guest at the house of another who

had a small child and the guest voluntarily cared for the child for a few minutes while

the parent absented him- or herself, that guest fell within the ambit of the section and

this was not strange if one had regard to the constitutional imperative in s 28(2) of

the Constitution, which provided that a child's best interests were of paramount

importance in every matter concerning the child.

Held, further, as to the sentence imposed on the first appellant for counts 1 and

2, that the magistrate had taken into consideration the fact that the convictions on

those counts stemmed from one continuous criminal transaction, and that was

reflected in the order that those sentences be served, in part, concurrently. In doing

so, the magistrate had not erred in any way.

Held, further, as to the disparity in sentences for count 2, that the magistrate

had correctly taken into account the different positions held by the respective

appellants over the child, in that she was the biological mother of the child whereas

the second appellant was not D's father, and that she had a greater responsibility

towards the child.

Held, further, as to the first appellant's argument that the sentence on count 3 was

excessive, given that her liability was only that of an accessory, that the crime of

being an accessory after the fact was one that was entirely sui generis and its

seriousness did not depend on the nature of the crime which the main perpetrator

committed, but on the manner in which an attempt was made to enable the

perpetrator to escape liability. The sentence imposed was appropriate.

Held, further, that the child could not express herself verbally so no

psychological profile could be drawn, but it appeared from the victim impact report

that the child still experienced nightmares from time to time and that this could be a

consequence of the abuse she had suffered. The court a quo had correctly rejected

the submission that the second appellant showed remorse, and the suggestion that

he had limited intellectual capacity was not his defence, nor did he tender it in

mitigation as an explanation for poor judgment, which may have been a substantial

and compelling circumstance, but instead he refused to take responsibility and

showed no remorse. The second appellant's personal circumstances were

outweighed by the seriousness of the offence and the need to protect society from

any possible repetition of this kind of abuse. The appeal against the sentence was

accordingly dismissed.

S v SEBOFI 2015 (2) SACR 179 (GJ)

Police — Duties of — Duty to investigate — Police officer involved in

investigation ought to appreciate that axiomatic line of enquiry was circumstances

which might offer corroboration or throw suspicion on truth or accuracy of complaint

— Similarly, any response by accused is relevant and must be taken seriously and

investigated — Investigating officers should ideally participate in running and

presentation of evidence to court and should be active in assisting prosecution.

Trial — The prosecution — Duties of — Presentation of evidence — Case cannot be