A Short Guide to Action Research, 2nd Edition

advertisement

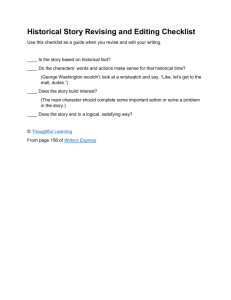

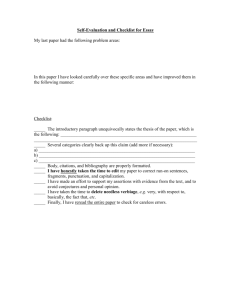

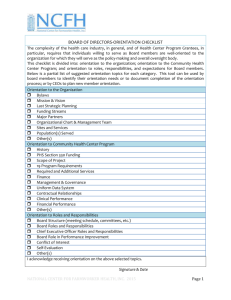

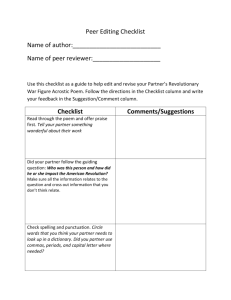

A Short Guide to nd Action Research, 2 Edition Chapter 8 Data Collection The goal of action research is to understand some element of your classroom by collecting data Data are any form of information, observations, or facts that are collected or recorded Collecting data is what separates action research from just writing a paper Action research is not writing what you think to be true, it is about collecting data and making conclusions based on that data Systematic Action research is systematic This means that before the research begins a plan is in place that describes what data you will collect and when, how, and how often you will collect it One way to ensure you are collecting data on a regular basis is to use a calendar or checklist You want to ensure that data are collected systematically and that all types are equally represented Data Collection Checklist Sample Type of data Date collected Date collected Date collected Date collected Date collected Quiz scores 8/18 8/25 9/2 9/9 9/16 Audio 8/13 8/19 8/26 9/1 9/17 Student writing 8/17 9/9 10/1 Homework 8/11 8/17 8/23 8/27 9/2 Journals 8/27 9/17 Conferen 8/20 ces 8/27 9/3 9/10 9/17 Date collected Date collected 9/10 9/16 Data Collection & Soil Samples Collecting data in an action research project is not a snapshot of a single incident like a test score Nor should data collection rely on a single type of data, such as only surveys or homework scores Action research is a series of quick looks taken at different times and in a variety of ways The author likens it to collecting soil samples: you gather bits of soil in different places over time A Television Sports Analyst Any biases of which you are aware should be stated up front so that readers are able to take this into account You are examining what is happening in the classroom and letting us read your thoughts as you analyze what you are perceiving and experiencing In this sense, you act as a sports analyst as you describe what is happening and break it down so that others can understand it Types of Data Collection in Action Research This section will describe 13 possible methods, some of which we will explore more in-depth later on Keep your action research simple and focused Trying to collect too many kinds of data will result in confusion and burnout The goal is not to have categories and labels with precise edges– it is to generate some ideas with fuzzy borders You need to find and adapt the methods that best suit your research question and teaching situation 1. Log or Research Journal Use this to describe each step of your research process You may choose to include a variety of data, such as observations, analyses, diagrams, sketches, quotes, student comments, scores, thoughts, and feelings Some choose to use their research journals to collect field notes and other forms of data while others keep items separate Computer logs are handy, but can be hard to read all at once on one screen 2. Field Notes- Your Observations Field notes are the written observations of what you see taking place in your classroom We will be reviewing this method in class later on Beginning researchers should stop thinking and just write what they see As you make many field notes over time, patterns will begin to emerge from this data 2. Field Note Types Thick Descriptions During This type of field note involves writing while teaching is taking place Few teachers are able to check out during their teaching to become an objective observer recording ongoing classroom events By becoming a researcher during your teaching, you run the risk of being a non-teacher, and thereby defeating the purpose of action research However, you can use the following steps to observe someone else’s classroom or setting Classroom Observation Steps 1. Enter the classroom as quickly and quietly as possible, selecting an inconspicuous spot 2. If students ask who you are, answer them— after a while, they won’t notice you are there 3. Begin taking notes without looking directly at students– this is less distracting 4. Smile 5. Write, don’t interpret- working memory has a limited capacity so you need to record the basics (you will have time for interpretations later on) 2. Field Note Types Quick Notes During Thick descriptions are difficult to record while teaching, but you can make quick notes, or jottings, during teaching This method works especially well with checklist forms of observation combined with field notes Quick Notes Steps 1. Keep a file in a safe spot for every student– this way, if anything interesting occurs, you can put the note in the file (files also help with overall assessment) 2. Keep a file related to the research projectwhenever an idea, observation, or insight occurs to you while teaching, put it here 3. Take notes on the margins or back of your lesson plans- most teachers get their best ideas during a lesson, so this is the logical place to take notes 2. Field Note Types Notes and Reflections After Many teachers prefer to record their observations later This method is most effective if you have kept good files on students as well as meaningful jottings Notes & Reflections Steps 1. After each lesson, make a quick note to yourself in your research journal- you can develop more detailed observations later 2. Record your insights and observations at the end of the day- this does not have to take a large amount of time 3. Reflect on the back of your lesson plans, especially if you are using lessons in your action research methodology 3. Checklists- Student Hew’s action research study utilized weekly checklists that her 5th graders would fill out (see p. 66) Each day of the workshop, students would use tally marks to indicate the activities they participated in that day The bottom three boxes are open ended, allowing for a variety of responses As the quarter progressed, Hew knew where her students were spending the majority of their time, about their writing topics, & skills learned 3. Checklists- Teacher Checklists can be introduced by teachers to indicate exactly what skills have been introduced or mastered and when These checklists also provide evidence that skills have been covered See Figure 8.3 on p. 67 One checklist for each student is kept in a binder, or electronically During writing time, it is a simple matter to take out this checklist and make a quick assessment Do not try to cover all attributes during a single session! One observation tells you little, but many short observations can tell you a lot 3. Checklists- Open-ended These checklists contain a list of skills with enough space for students or teachers to comment on abilities, understanding, or usage of skills (see Figure 8.4 on p. 69) This provides you with an accurate indicator of students’ level of understanding It also helps you to plan instruction to meet specific needs 4. Conferences & Interviews There is an important difference between both In a conference, one or more students talk about their work or some aspect of classroom functioning Prompts may be used, but lists of planned questions are not In an interview, students respond to planned questions, which are best conducted on an individual basis 4. Individual Student Conferences Students should always do the majority of the talking and lead the conversation This exchange is open-ended, and can last anywhere from 2-15 minutes Figure 8.5 on p. 69 provides a list of questions you can use When conferencing, take notes, but do not try to get a verbatim transcript Record only those items you feel are important, such as strengths, weaknesses, skills learned, etc. 4. Individual Student Conferences You may want to design some kind of a checklist to use during this conference After you have done this process a few times, you will get a good sense of what to record and how to best record it A checklist can be used to keep track of students and conference times (see Figure 8.6 on p. 70) Conferences can also be used to address social or interpersonal issues See Jason Hinkle’s example on bottom of p. 68 4. Small Group Conferences You meet with 3-8 students at one time You are able to see a number of students fairly quickly and watch their interaction Students can also hear and respond to other students’ thoughts Small group conferences can also be adapted for a variety of situations Never assume students know how to function effectively in groups, so provide some structure (see figure 8.7 on p. 71) Each group can use a checklist to report their progress (Appendix G & p. 71) 4. Interviews Interview questions should be asked in the same order each time to maintain consistency See Figure 8.9 on p. 72 which demonstrates a hierarchy of questions Keep interviews short and use open-ended questions Use a tape recorder so you won’t be bogged down with field notes at the time of the interview 5. Video- and Audiotapes Video provides you with information related to students’ nonverbal behaviors, location, movement, and a general overview of your teaching techniques Video is obtrusive at first, but if you do it often, its effect diminishes Audiotapes are quicker, easier, less intrusive, and natural, but you might miss nonverbal behaviors 6. Data Retrieval Charts DRC’s are visual organizers that are used to help you or your students collect and organize information Pam Bauer’s 5th grade class created the DRC in Figure 8.10 on p. 72 to determine the types of desserts chosen by students This DRC provided data that could then be quantified and compared across grade level or over time Gender differences can easily be compared by including an extra column (Figure 8.11 on p. 73) 7. Rating Checklist A rating checklist specifies traits you are looking for in a product or performance It allows the observer to assign levels of performance to each trait A rubric is similar, but a checklist uses one-word indicators (see p. 74) This rating checklist was used at the end of a science unit where students evaluated their own level on one side and teachers on the other 8. Students’ Products or Performances Samples of students’ work can be excellent data sources You only need to collect representative samples at different periods of time to give you a feel for students’ performances and changes over time It is often helpful to create a flexible schedule to determine when you will collect this work 8. Product & Performance Figure 8.13 on p. 75 shows a product and performance assessment form (PPAF) This rating checklist can be used to analyze and evaluate any type of product or performance (see also Appendix H) These forms can be used by both students and teachers for self-assessment 8. Writing Samples Figure 8.14 on p. 75 contains a rating checklist that can be used to analyze and evaluate any kind of writing This is a good teaching tool in that it forces you to define exactly what is expected and puts the onus on you to teach each skill associated with those expectations Students also appreciate the precise feedback this form provides 8. Independent Research Projects Figure 8.15 on p. 76 shows a rating checklist used for independent research projects Notice that all elements of action research are found on this checklist Understanding action research will enable you to incorporate more effectively methods of science, inquiry, and research into your own teaching These skills can be taught to students for use in their own projects 8. Scores & Other Quantifiable Data Students’ scores on tests, homework, quizzes, grades, and standardized assessment measures can also be used as a data source These should never be used as the only source of data 9. Surveys This section was already addressed indepth in our survey lab, but it is a good review to look over See pp. 76-77 10. Attitude & Rating Scales Attitude Scales Students respond by indicating their level of agreement or disagreement A 5 point rating is most effective for grades 3 and up With younger students, provide graphics, as on p. 78 Rating Scales Used to indicate the strength of a response Often used to determine how much, how often, or how many times something occurs Both are considered survey-type questions 11. The Arts The arts are another way of seeing the world and can be used to bring a different level of understanding to your action research Visual Sociology exemplar Artists and researchers are alike in that the work of both are like lenses through which reality is interpreted and translated Certain kinds of art lend themselves to action research: 2-dimensional art Language arts Student’s use of these mediums along with your analysis 12. Archival Data This includes past grades, test scores, cumulative folders, health records, parental occupation, or attendance records Make sure you follow your school’s procedures for obtaining access to this data Make sure all data are used and reported in an ethical manner 13. Websites, Class Journals, E-mail Websites can be used to create a conversation between students- the transactions can be printed as a data source The class journal is a low-tech version of the website option- both need supervision and guidelines so that offensive or hurtful material is not allowed E-mail is a fast and private form of communication between students and teachers- students could email you about a variety of topics Lab Activity- Artifact Analysis Make sure everyone has an Artifact Analysis worksheet for this activity 1. Work in small groups- 3-4 tops 2. There should be at least one form of artifact data per group- those with extra, share with another group 3. Use at least one of the following tools from chapter 8 in your analysis, adapting the tool to fit your data set: Figure 8.3 p. 67 Figure 8.4 p. 69 Figure 8.10 p. 72 or Figure 8.11 p. 73 Figure 8.12 p. 74 Figures 8.13 or 8.14 p. 75