content is excerpted here

advertisement

1

Terms Used by Narratology and Film Theory

[from:

javascript:popUp('http://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/narratology/terms/narrativet

ermsmainframe.html');]

T

HE FOLLOWING TERMS are presented in alphabetical order; however,

someone beginning to learn narratology needs to stay conscious of the fact that the

same terms sometimes refer to the same or analogous things (eg. story and fabula or

flashback and analepsis). I have tried to indicate terms that are related, as well as those terms that

are used differently by two different narratologists. For an introduction to the work of a few

narratologists currently influencing the discipline, see the Narratology Modules in this site.

Whenever a defined term is used elsewhere in the Guide to Theory, a hyperlink will eventually

(if it does not already) allow you to review the term in the bottom frame of your browser

window. The menu on the left allows you to check out the available terms without having to

scroll through the list below. Note that the left-hand frame works best in Explorer, Mozilla, and

Netscape 4; you may experience some bugs in Netscape 6 and Opera. (See the Guide to the

Guide for suggestions.) I will also soon provide an alternate menu option; for now, just scroll

down.

A

Analepsis and Prolepsis:

What is commonly referred to in film as "flashback" and "flashforward." In other words,

these are ways in which a narrative's discourse re-order's a given story: by "flashing back"

to an earlier point in the story (analepsis) or "flashing forward" to a moment later in the

chronological sequence of events (prolepsis). The classic example of prolepsis is

prophecy, as when Oedipus is told that he will sleep with his mother and kill his father.

As we learn later in Sophocles' play, he does both despite his efforts to evade his fate. A

good example of both analepsis and prolepsis is the first scene of La Jetée. As we learn a

few minutes later, what we are seeing in that scene is a flashback to the past, since the

present of the film's diegesis is a time directly following World War III. However, as we

learn at the very end of the film, that scene also doubles as a prolepsis, since the dying

man the boy is seeing is, in fact, himself. In other words, he is proleptically seeing his

own death. We thus have an analepsis and prolepsis in the very same scene.

B

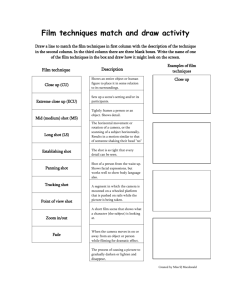

Bridging Shot :

In film, a shot that attempts to "bridge" or smooth out a jump cut, thus giving the

impression of continuity even though the jump cut has created a spatial or temporal break

of some sort.

2

C

Crane Shot :

In film, a shot in which the entire camera is moving in one direction (often while on a

crane, hence the term). Also sometimes called a boom shot.

D

Diegesis:

A narrative's time-space continuum, to borrow a term from Star Trek. The diegesis of a

narrative is its entire created world. Any narrative includes a diegesis, whether you are

reading science fiction, fantasy, mimetic realism, or psychological realism. However,

each kind of story will render that time-space continuum in different ways. The

suspension of disbelief that we all perform before entering into a fictional world entails an

acceptance of a story's diegesis. The Star Trek franchise is fascinating for narratology

because it has managed to create such a fully realized and complex diegetic universe that

the narratives of all five t.v. shows (TNG, DS9, STV, Enterprise,, the original Star Trek)

and all the movies occur, indeed coexist, within the same diegetic time-space.

Discourse and Story:

"Story" refers to the actual chronology of events in a narrative; discourse refers to the

manipulation of that story in the presentation of the narrative. These terms refer, then, to

the basic structure of all narrative form. Story refers, in most cases, only to what has to be

reconstructed from a narrative; the chronological sequence of events as they actually

occurred in the time-space (or diegetic) universe of the narrative being read. The closest a

film narrative ever comes to pure story is in what is termed "real time." In literature, it's

even harder to present material in real time. One example occurs at the end of the Odyssey

(Book XXIII, pages 467-68); Odysseus here presents the story of his adventures to

Penelope in almost pure "story" form, that is, in the chronological order of occurence.

Stories are rarely recounted in this fashion, however. So, for example, in the Odyssey, we

do not begin at the chronological start of the story but in medias res, when Odysseus is

about to be freed from the isle of Calypso (which actually occurs nearly at the end of the

chrnologlical story which Odysseus relates to Penelope on p. 467). Discourse also refers

to all the material an author adds to a story: similes, metaphors, verse or prose, etc.. In

film, such manipulations are extended to include framing, cutting, camera movement,

camera angles, music, etc..

E

Establishing Shot :

In film, a camera shot that establishes a scene, often as a long shot. This is a common

maneuver at the beginning of Hollywood films, especially if the setting plays a significant

role (eg. Sleepless in Seattle).

Eye-Line Shot :

In film, a sequence of two shots. In the first, you are shown a character looking; in the

second you are presented with what he or she sees, as if you were looking out of that

character's eyes (in other words, an objective treatment of a character followed by a POV

3

shot focalized through that character).

F

Fabula and Sjuzhet:

Fabula refers to the chronological sequence of events in a narrative; sjuzhet is the representation of those events (through narration, metaphor, camera angles, the re-ordering

of the temporal sequence, and so on). The distinction is equivalent to that between story

and discourse, and was used by the Russian Formalists, an influential group of

structuralists. For a web page dedicated to the distinction between fabula and sjuzet, click

here.

First-Person Narration:

The telling of a story in the grammatical first person, i.e. from the perspective of an "I,"

for example Moby Dick, including its famous opening: "Call me Ishmael." This form of

narration is more difficult to achieve in film; however, voice-over narration can create the

same structure. Orson Welles achieves similar effects in Citizen Kane through, for

example, the judicious use of POV and over-the-shoulder shots. Such narrators can be

active characters in the story being told or mere observers. First-person narration tends to

underline the act of transmission and often includes an embedded listener or reader, who

serves as the audience for the tale. First-person narration focalizes the narrative through

the perspective of a single character. The question of motivation or psychology is

therefore often raised: why is this narrator telling us this story in this way and can we trust

him? For this reason, unreliable narrators are not uncommon.

Focalize (focalizer, focalized object):

The presentation of a scene through the subjective perception of a character. The term can

refer to the person doing the focalizing (the focalizer) or to the object that is being

perceived (the focalized object). In literature, one can achieve this effect through firstperson narration, free indirect discourse, or what Mikhail Bakhtin refers to as dialogism

(see Module on Bakhtin). In film, the effect can be achieved through various camera

tricks and editing, for example POV shots, subjective treatment, over-the-shoulder shots,

and so on. Focalization is a discursive element added to a narrative's story.

Frame Narrative:

A story within a story, within sometimes yet another story, as in, for exmple, Mary

Shelley's Frankenstein. As in Mary Shelley's work, the form echoes in structure the

thematic search in the story for something deep, dark, and secret at the heart of the

narrative. The form thus also resembles the psychoanalytic process of uncovering the

unconscious behind various levels of repressive, obfuscating narratives put in place by the

conscious mind. As is often the case (and Shelley's work is no exception), a different

individual often narrates the events of a story in each frame. This structure of course also

leads us to question the reasons behind each of the narrations since, unlike an omnicient

narrative perspective, the teller of the story becomes an actual character with concomitant

shortcomings, limitations, prejudices, and motives. The process of transmission is also

highlighted since we often have a sequence of embedded readers or audiences, A famous

example in film of such a structure is Orson Welles' Citizen Kane. See also the definition

4

for narration.

G

Gaze:

In feminist film criticism, this term usually refers to the predominantly male gaze of

Hollywood cinema, which tends to objectify women. Feminist critics examine carefully

the ways that camera angles and film editing tends to focalize women as objects

perceived by voyeuristic men. See also scopophilia. The term is influenced by both

Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

Gaze Shot:

In film, a shot of a character gazing at something; such a shot is often followed by a POV

shot, in which case it is termed an eye-line shot.

H

Hermeneutic and Proairetic Codes:

The two ways of creating suspense in narrative, the first caused by unanswered questions,

the second by the anticipation of an action's resolution. These terms come from the

narratologist Roland Barthes, who wishes to distinguish between the two forces that drive

narrative and, thus by implication, our own desires to keep reading or viewing a story.

The hermeneutic code refers to those plot elements that raise questions on the part of the

reader of a text or the viewer of a film. For example, in the Star Trek: TNG episode,

"Cause and Effect," we see the Enterprise destroyed in the first five minutes, which leads

us to ask the reason for such a traumatic event. (See the Lesson Plan on Star Trek for the

clip and a class discussion of the scene.) Indeed, we are not satisfied by a narrative unless

all such "loose ends" are tied. Another good example is the genre of the detective story.

The entire narrative of such a story operates primarily by the hermeneutic code. We

witness a murder and the rest of the narrative is devoted to determining the questions that

are raised by the initial scene of violence. The proairetic code, on the other hand, refers to

mere actions—those plot events that simply lead to yet other actions. For example, a

gunslinger draws his gun on an adversary and we wonder what the resolution of this

action will be. We wait to see if he kills his opponent or is wounded himself. Suspense is

thus created by action rather than by a reader's or a viewer's wish to have mysteries

explained.

I

in medias res:

Technical term for the epic convention of beginning "in the middle of things," rather than

at the very start of the story. In the Odyssey, for example, we first learn about Odysseus'

journey when he is held captive on Calypso's island, even though, as we find out in Books

IX through XII, the greater part of Odysseus' journey actually precedes that moment in

the narrative. Of course, films and written tales often begin in the thick of things and fill

in the background later; in other words, narrative regularly reworks discursively the

simple chronology of its story.

5

J

Jump Cut:

In film, an editing cut that creates a break in time or space in what would otherwise be a

continuous sequence. The same action may, for example, "jump" forward in time or

suddenly change scene.

K

L

Lap Dissolve:

Technical term for when in film one scene fades into the next. A good example is the

sequence of lap dissolves in La Jetée that ends with the protagonist's love object opening

her eyes.

Lateral Wipe:

A highly stylized edit whereby one scene replaces the former scene by appearing to wipe

it away from right to left or left to right. The technique is hardly ever used anymore but

was a common cinematic technique of the forties and fifties.

Long Shot:

In film, a view of a scene that is shot from a considerable distance, so that people appear

as indistinct shapes. An extreme long shot is a view from an even greater distance, in

which people appear as small dots in the landscape if at all (eg. a shot of New York's

skyline).

M

Match Cut:

Technical term for when a director cuts from one scene to a totally different one, but has

objects in the two scenes "matched," so that they occupy the same place in the shot's

frame. The director thus makes a discursive alignment between objects that may not have

any connection on the level of story. Match cuts offer directors with one way to create

visual metaphors in film since the match cut can suggest a relation between two disparate

objects

Metadiegetic and Extradiegetic:

Gérard Genette distinguishes among diegetic narratives (the primary story told);

metadiegetic narratives (stories told by a character inside a diegetic narrative); and

extradiegetic narratives (stories that frame the primary story).note

N

Narration:

Narration refers to the way that a story is told, and so belongs to the level of discourse

6

(although in first-person narration it may be that the narrator also plays a role in the

development of the story itself). The different kinds of narration are categorized by each

one's primary grammatical stance: either 1) the narrator speaks from within the story and,

so, uses "I" to refer to him- or herself (see first-person narration); in other words, the

narrator is a character of some sort in the story itself, even if he is only a passive observer;

or 2) the narrator speaks from outside the story and never employs the "I" (see thirdperson narration). See also third-person omniscient narration; third-person-limited

narration; and objective treatment.

O

Objective Treatment:

An objective treatment of a scene is the most common use of the camera in film and

television; we are simply presented with what is before the camera in the diegesis of the

narrative. We are not seeing the scene through the perspective of any specific character,

as we do in POV shots or in a subjective treatment of events. "objective treatment"

corresponds to "third-person narration" in literature.

Over-the-Shoulder Shot:

In film, a shot that gives us a character's point of view but that includes part of that

character's shoulder or the side of the head in the shot. There are numerous examples in

Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, especially of the focalizing gaze of the nameless reporter;

indeed, we are often given over-the-shoulder shots that include his glasses, thus selfreflexively underlining the fact of the focalization (eg. bi-focals).

P

POV or Point-of-View Shot:

A sequence that is shot as if the viewer were looking through the eyes of a specific

character. The shot is a common trick of the horror film: that is, we are placed in the

position of the killer who is slowly sneaking up on a victim. (Note that horror directors

sometimes "cheat" with this device; that is, after a building of suspense, it can also turn

out that we were not in the position of the killer after all.)

Q

Real Time:

In film, when a sequence is presented exactly as it occurs, without any edits or jumps in

7

time. The recent television series, 24, attempted to present the viewer with real time for

each of its 24 episodes, with the action in each episode lasting exactly one hour. The

exact time of the story action is therefore equal to the time it takes to view that action.

The show made up for tediousness by jumping between actions occurring at the same

time. In general, film or video rarely attempts to present you with real time since the most

interesting aspects of a narrative tend to reside in the discursive re-organization of the

chronological story.

R

S

Scopophilia:

Literally, the love of looking. The term refers to the predominantly male gaze of

Holloywood cinema, which enjoys objectfying women into mere objects to be looked at

(rather than subjects with their own voice and subjectivity). The term, as used in feminist

film criticism, is heavily influenced by both Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

Shock Cut:

A cut in a movie that juxtaposes two radically different scenes in order to shock the

viewer. A famous example is the opening sequence in Stanley Kubrick's 2001 in which a

prehistoric man throws a bone into the air, which then shock cuts (and match cuts) to an

oblong star-ship in space.

Subjective Treatment:

Whereas in a POV shot we are looking through the eyes of a character in the present and

seeing something that is happening in the diegesis of the narrative, in a series of shots

presented as a subjective treatment of events we see through the "mind's eye" of the

character. We might be seeing a vision, a memory, or a hallucination. A good example are

the many instances of the subjective treatment of events in the X-Files episode, "Jose

Chung's From Outer Space," whereby we are presented with the false and manipulated

memories of various characters. In earlier films and tv shows, such sequences often began

with wavy lines, a distorted opening sequence, or a halo effect. In the SNL skit (and later

movie), "Wayne's World," Wayne (played by Mike Myers) alludes to such stylistic

devices by waving his hands in front of the camera before a dream or wish-fulfillment

sequence.

Suture:

The techniques used by film to make us forget the camera that is really doing the looking.

Laura Mulvey argues that there are, in fact, three looks implied by film: 1) the look of the

camera itself; 2) the look of the audience watching the film; and 3) the look of the

characters on screen (Mulvey 25). In traditional Hollywood cinema, we are invited

(through various tricks of editing, camera angles, etc.) to identify with the look of the

male characters so that we will forget the mechanical look of the camera and our own

invested look at the screen. As Kaja Silverman explains, "This sleight-of-hand involves

attributing to a character within the fiction qualities which in fact belong to the machinery

8

of enunciation: the ability to generate narrative, the omnipotence and coercive gaze, the

castrating authority of the law" (232).

T

Third-Person Limited Narration or Limited Omniscience:

Focussing a third-person narration through the eyes of a single character. Even when an

author chooses to tell a narrative through omniscient narration, s/he will sometimes (or

even for the entire tale) limit the perspective of the narrative to that of a single character,

choosing for example only to narrate the inner thoughts of that one character. The

narrative is still told in third-person (unlike first-person narration); however, it is clear

that it is, nonetheless, being told through the eyes of a single character. A famous

example of this form of narration is James Joyce's "The Dead" (in Dubliners). A narrative

can also shift among various third-person-limited narrations. (See also focalize.)

Third-Person Narration:

Any story told in the grammatical third person, i.e. without using "I" or "we": "he did

that, they did something else." In other words, the voice of the telling appears to be akin

to that of the author him- or herself. This is perhaps the most common sort of narration

and was particularly popular with the nineteenth-century realist novel. See also thirdperson omniscient narration; third-person-limited narration; and objective treatment.

Third-Person Omniscient Narration:

This is a common form of third-person narration in which the teller of the tale, who often

appears to speak with the voice of the author himself, assumes an omniscient (allknowing) perspective on the story being told: diving into private thoughts, narrating

secret or hidden events, jumping between spaces and times. Of course, the omniscient

narrator does not therefore tell the reader or viewer everything, at least not until the

moment of greatest effect. In other words, the hermeneutic code is still very much in play

throughout such narrations. Such a narrator will also discursively re-order the

chronological events of the story.

Tracking Shot:

In such a film shot, the camera is literally running on a track and thus smoothly following

the action being represented or perhaps thus giving the viewer a survey of a particular

setting.

U

Unreliable Narrator:

A narrator that is not trustworthy, whose rendition of events must be taken with a grain of

salt. We tend to see such narrators especially in first-person narration, since that form of

narration tends to underline the motives behind the transmission of a given story. There

are numerous famous examples in literature (James' "Turn of a Screw" is a superb

example) and a few notable examples in film (Citizen Kane perhaps most famously

among them).

9

V

Voice-Over Narration:

In voice-over narration, one hears a voice (sometimes that of the main character)

narrating the events that are being presented to you. A classic example is Deckard's

narration in the Hollywood version of Ridley Scott's Bladerunner. This technique is one

of the ways for film to represent "first-person narration," which is generally much easier

to represent in fiction.

W

Wipe:

A smoothly continuous replacement of one shot by another shot, as if the new shot were

"wiping away" the old one. The wipe usually proceeds from left to right or vice-versa, but

can also proceed from top to bottom or vice-versa.

X

Y

Z

Zoom:

When a stationary camera moves in or away from an object by shortening its focal length.

The same effect can be achieved by pushing in or pulling back the camera, in which case

it is no longer properly a "zoom" shot.