Immigrants and Refugees An - National Association for the

advertisement

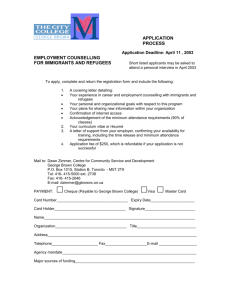

GUESS WHO’S COMING TO AMERICA? IMMIGRANTS AND REFUGEES 2011 Sharing What We Know Maria Green Assistant Director of Prekindergarten and Homeless Education Program Department: Student Diversity & Learning Phone: 512-464-5977 E-mail: Maria_Green@roundrockisd.org Sharing What We Know Vicky Dill Senior Program Coordinator, Texas Homeless Education Office, University of Texas at Austin 512-475-9715 vickydill@austin.utexas.edu Challenges Immigrant and Refugee Students Face http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=- YNj1ad8vDM&feature “Believing in my Culture and Religion” Liaisons Should Model Cultural Competence & Courtesies Know strategies to show commitment to struggling immigrant and refugee families who may have become homeless. Understand the difference between cultural competence, cultural tendencies, and stereotyping. Cultural Competence and Courtesies Augments individual liaisons’ intrapersonal skills to better serve the needs of homeless immigrants and refugees. Reflects the Mosaic or Tapestry symbol: America is not really a melting pot where cultures mix until they are indecipherable, but rather a picture woven of distinct threads. Immigrants and Refugees How are they different under the law? Immigrants and Refugees An “Immigrant” is a person who permanently moves to a country different from that of their birth. A “Refugee” is a person who has fled their country of birth due to fear of persecution, war, or imminent danger. Students and families can be both of these. Cultural Competence Includes the understandings that: each person in any cultural group is first and foremost, an individual. cultural groups vary immensely within the culture. learning about “cultural tendencies” is not the same as “stereotyping.” Strategies to Increase Cultural Competence and Courtesies Read and learn about the culture; visit and share stories with youth and families; Evaluate your own assumptions and values about the culture; consider the values of the culture when serving students; Learn a few phrases of the students’ home language; Learn and pronounce students’ actual names, not just the “American” version. Helpful Definitions Cultural Tendencies: “Shared beliefs, traditions, and values of a group of people.” Race: “A classification that distinguishes a group of people from one another based on physical characteristics such as skin color and other biological attributes.” Ethnicity: “The social definition of groups of people based on shared ancestry and includes race, customs, nationality, language and heritage.” Why Learn these Tendencies? “By increasing their understanding of tendencies within various cultural groups, it is easier for professionals to view students as individuals within the framework of their community and culture . . .” (Roseberry-McKibbin, 2007). Top 8 Countries Sending Refugees (as opposed to immigrants) to the US, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) The U.S. admitted 60,192 refugees in FY 2008, the latest data available from UNHCR. This included many Cuban and Haitian nationals admitted for asylum. Who Receives Asylum? Political refugees who are fleeing arrest, torture, or other forms of oppression An individual who receives asylum is called an “asylee” or refugee. Top 8 Countries Sending Refugees to the U.S. (UNHCR) 1. Cuba (23,294) 2. Iraq (13,755 ) 3. Burma (12,852), 4. Thailand (5,279) 5. Iran (5,257), 6. Bhutan (5,244), 7. Burundi (2,875), and 8. Somalia (2,510) Are Refugees Stably Housed? Because of the vetting process which starts for refugees at the UNHCR and progresses through other clearinghouse agencies towards, at the local level, a faith-based agency that resettles refugees, most new refugees are not homeless. Refugees: Six top states that received them: 1. Florida (21,026) 2. California (9,739 3. Texas (5,712), 4. New York (3,784), 5. Michigan (3,436), 6. Arizona (3,212). Cultural Understandings of the Refugees (as opposed to immigrants) Who Came in the Largest Numbers to the United States Cuba Iraq Haiti Research drawn from “Bridging Refugee and Children’s Services” (BRYCS) at www.brycs.org Cuba Sent the Most Refugees Cubans may not know religious distinctions in the U.S. as religion was outlawed prior to 1991 in Cuba. Catholicism and Santeria (an African variation) are the most common religions. Many Cuban parents, like other refugees, discipline their children in ways that vary greatly from discipline customs in the U.S. TV is not watched daily in Cuba; Cuban refugees, like other refugees families, may be wary of TV violence for their children. Iraq: The Second Most Populous Refugee Group Special programs exist within the UNHRC to assist Iraqis who are refugees from the war; Stigmatization and bullying in the U.S. are common for Iraqi students; In many Iraqi families, the mother is responsible for the discipline of the children; physical punishment is permitted by the parents, but not by the teachers; In Iraq, the whole neighborhood may discipline the child; in the U.S. this is uncommon. Iraq (Cont.) Many Iraqi refugees find citizens in the U.S. are more sensitive to the differences between Shite and Sunni than Iraqis are. Iraqi families appreciate when their student(s) can find or have an Arab mentor. Many Iraqi families have made downward adjustments in their lifestyle since leaving Iraq and are surprised at the lack of social safety nets in the U.S. Haiti: The Third Most Populous Refugee Group Haitians do not want to be stereotyped as a people who are either dominating, corrupt, and violent (ruling class), or uneducated, passive, and not loyal (everyone else). Haitians tend to see migration as a primary mode to better themselves and survive. Because of their history, Haitians may think of government as generally elite and predatory. Coming to America Isn’t Easy http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZtipuczPT tY “Manifest: Coming to America” Refugee Stability in the US Post arrival stability varies greatly. Refugees come under the care of a voluntary agency or “volag.” “Volags” assist the refugees for approximately 90 days after arrival. Refugees are eligible for welfare and Medicaid for about the first 8 months. Until they become citizens, many benefits are not available to them. Refugee Stability in the US 30 years ago, refugees received a minimum of 1.5 years of assistance and 3 years of reimbursement for medical expenses. Today, refugees admitted to the US tend to be more fragile victims of torture, rape, persecution and other forms of violence. Yet there are fewer welfare benefits, no medical safety net, and fewer employment opportunities for refugees than ever before. Update on Immigrants, 2011 Documented Immigrants Coming to the U.S. Top 10 countries of origin for documented immigrants Mexico (166,271) Dominican Republic (33,230) India (64,857) Pakistan (25, 972) China (60,720) Haiti (24, 726) Philippines (53,171) South Korea (23,077) Vietnam (39,915) El Salvador (17, 193) Extending Cultural Understanding and Courtesies: Hispanic Families Many Hispanic families tend to hold teachers in high regard. Many Hispanic families emphasize the needs of the group and cooperation over the needs of individuals and competition. Educational levels vary greatly; immigrants’ knowledge of Spanish may also vary greatly. Some Hispanic families may not understand why their daughters need to graduate from high school instead of bearing children. Extending Cultural Understanding and Courtesies: Asian/Indian Families Many Asian/Indian families greatly emphasize family interdependence and loyalty. Fathers may hold the highest authority and children are taught to “defer” to adults. If children behave badly, the family may “lose face.” Children may be controlled with physical punishments. Many Asian/Indian families prefer family care of their preschool children, so preschoolers may have never been outside the home or in “strangers’” care prior to kindergarten. These children may need longer to learn to socialize. Undocumented: A Population of Promise There are between 65,000 and 1.8 million undocumented children living in the U.S. Undocumented Immigrants As of February 2011, the non-partisan Pew Hispanic Center counts roughly 11.2 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., up from 8.4 million in 2000. About 5% of all members of the U.S. labor force are undocumented. From What Countries do Undocumented Immigrants Arrive? 58% are Mexican (6.5 million); 23 % from other Latin American countries; 11% from Asia; 4% from Europe and Canada, 3% from Africa. Only about 8% of all U.S. newborns (350,000) have one undocumented parent. Undocumented? Documented? Refugees are seldom allowed to immigrate without full documentation. Immigrants can be either documented or undocumented. Serving Immigrants in School Both School Districts and Immigrants have Rights. Immigrants and Refugees alike should be treated with sensitivity and an awareness of cultural tendencies. Liaisons may wish to acquaint themselves with state laws in order to know if immigrants need to be documented in order to acquire ID’s and drivers’ licenses. APPREHENSIONS CAN LEAVE YOUTH HOMELESS COURTESY http://www.bernardokohler.org/Juvenile.htm May 6, 2011 Joint Letter from the DOJ and DOE Cites Titles IV and VI of the federal code that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin. Cites Plyler v. Doe which makes it clear that the citizen status of a student is irrelevant to their entitlement to an education. Cites Brown v. Board of Education in encouraging districts to review their documents in light of this notice. DOJ Requests to the State of Alabama November 1 letter from the DOJ about Alabama’s SB 56 and the potential to chill enrollment; May be preliminary to further action; Focuses on extent of withdrawals (items 2 & 3) and tracks data on a monthly basis. Treating Students with Dignity Districts may require residency information via copies of water or phone bills; however, a district must recognize that immigration status is not relevant to residency; Districts may request birth certificate information to gauge a student’s age and to fulfill requirements to supply data; however, failure to supply this data cannot lead to a denial of enrollment. Treating Students with Dignity (cont.) Districts that choose to request social security numbers must demonstrate that the request is voluntary; they must provide the statutory reason for the request, apply the same requests to all students, and never deny enrollment based on failure to provide such information. Encourages district officials to visit the local Office of Civil Rights to see if their documents are in compliance. When Disagreement Arises Ensure that language on the Student Residency Questionnaire warns of the consequences of providing false information. For example:” Presenting a false record or falsifying records is an offense under Section 37.10, Penal code, and enrollment of the child under false documents subjects the person to liability for tuition or other costs. TEC Sec. 25.002(3)(d).” Immediately start the Dispute Resolution Process Preserving Opportunity for Undocumented Students Immigration enforcement may leave undocumented students homeless; Where raids on undocumented populations have occurred, children/students are always affected; In some cases, schools are warned that raids are about to occur, and staff can plan for a safe place for the children to go when their parents have been detained; Liaisons May Be Able to Help Ensure the district is following federal enrollment protections. Encourage and assist students who disclose their status as undocumented to get legal assistance. Ensure that homeless undocumented students whose parents have been detained have caregivers or know who to call. Encourage students to take upper level courses and provide scholarship assistance (NASSP guidelines, May 2011). Potential Paths to Legal Status: Immigrant Students “Special Immigrant Juvenile Status” path requires a student who is unmarried and under 21 years meet certain eligibility criteria such as abuse, abandonment, maltreatment, etc. Asylum path: students who have suffered persecution at home on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, etc. Potential Paths to Legal Status (cont.) Uvisa – student has suffered physical or mental abuse from a crime and they will be helpful in prosecution of that crime; VAWA (Violence Against Women Act) – female students who have experienced extreme cruelty such as female genital mutilation or similar abuse or children of female victims of the same; T-Visa – Students who have been sex trafficked or experienced forced labor. SRQ’s in the Native Language: A Sign of Cultural Courtesy The New York City Department of Education has SRQ’s available in English, Arabic, Chinese, Korean, Spanish, Bengali, Haitian Creole, Russian, and Urdu. The Madison (WS) Metropolitan School District has an SRQ in Hmong. Many other LEA’s provide appropriate translations of important forms http://center.serve.org/nche/forum/enrollme nt.php . Shared Fears and Challenges Forced Repatriation and retribution in the homeland: refugees may face forced labor camps, prison, and torture; Post Traumatic Stress Disorder common; Lack of education and basic resources in the home country or refugee camps; Rules and expectations differ in the new land; Lack of acquaintance with technology. Identifying Homeless Immigrants and Refugees Use of SRQ and/or translators in the families’ native language(s). Enlist the help of the greater immigrant and refugee population; do not assume refugees who came under a program are remaining stably housed or that all immigrants have relatives who can help them. An Increasing Number of both Immigrants and Refugees are Becoming Eligible for McKinneyVento Services Services for Immigrant Families within the Community Immigration Legal Services – Catholic Charities of Central Texas Lawyer Referral Service of Central Texas Immigration Lawyer Search- American Immigration Lawyers Association Refugee Services of Texas, Inc. Navigating the Education System This is one of the most formidable challenges an immigrant or refugee can face. Some cultures consider parents entering a classroom to be rude behavior. Some families that do not have documents or records will not even attempt to enroll their children in school. Fear can be interpreted as lack of interest or motivation. Helping Refugees from Mexico and South America: DISTRICT EXPERIENCE AND QUANDARIES: MARIA GREEN, HOMELESS LIAISON, ROUND ROCK ISD, ROUND ROCK, TX. NCLB (Title III) Guidance IMMIGRANT-INDICATOR-CODE indicates whether the student is an identified immigrant under the definition found under Title III of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), where the term ‘immigrant children and youth’ is defined as, “individuals who are aged 3 through 21; were not born in any state; and have not been attending one or more schools in any one or more states for more than 3 full academic years. The term ‘State’ means each of the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. (See P.L. 107-110 Title III, Part C, § 3301(6).) NCLB (Title III) Guidance Special Instructions Immigrant status under the Title III – Language Instruction for Limited English Proficient and Immigrant Students of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, should not be confused with immigrant status as defined for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Districts should not assume responsibility for determining the extent to which students are legal or illegal immigrants under DHS regulations. Definition of immigrant should not be confused with definition used for state assessment purposes or definition used for student eligibility to English I for Speakers of Other Languages or English II for Speakers of Other Languages taught in high school. Texas is required to use the federal definition under Title III of NCLB in order to determine immigrant student counts for funding and for coding in PEIMS. Contact the NCLB Program Coordination Division for clarifications regarding immigrant status at 512-463-9374. Public Education Information System (PEIMS) for Texas Public Schools Public Education Information System (PEIMS) for Texas Public Schools Identifying Homeless Immigrants and Refugees within the ISD Use of SRQs and the intake process to provide services through Families In Transition (FiT) program Notification to campus contact regarding the eligibility status of student Progress monitoring of students for the duration of the school year Student Residency Questionnaire Intake Process and Services Intake Process and Services Intake Process and Services