Using the Subjunctive - Warren County Public Schools

advertisement

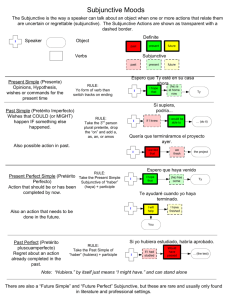

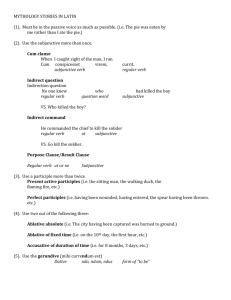

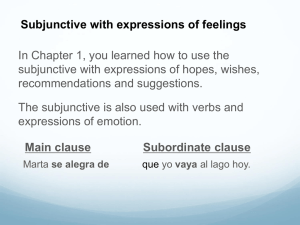

Using the Subjunctive Noun Clauses The subjunctive tends to be a somewhat difficult concept for native speakers of English, yet it is used in Spanish all the time. For that reason, we tend to spend a lot of time teaching it once students reach the 2000 level. In fact, in some textbooks, the principal grammar lessons in the last third of the book involve the subjunctive. So what IS the subjunctive? It’s a mood. Verbs have moods. There are three to choose from—subjunctive, indicative, and imperative. Commands are the imperative mood. Most other verbs are indicative. The very first tense you learned was present indicative. Then you learned preterit indicative and then imperfect indicative. If you’ve done the “Subjunctive Formation” slide show, you’ve learned the present subjunctive; if not, that’s where you’re headed next. “Mood” does not mean “tense.” You can have present subjunctive or present indicative or present imperative. “Tense” means “time.” In fact, the Spanish word for tense is “tiempo”—which is also the word for “time.” “Mood” has to do with the way an action is viewed and doesn’t have anything to do with time. 99% of the time, the subjunctive is used in a dependent clause, not the main clause. But what happens in the main clause can make the subjunctive necessary in the dependent clause. We have a few examples of the subjunctive in English: If I were you, I’d study more. This is called a “contrary-to-fact” clause. I’m NOT you, so “if I were you” is contrary to fact. “Were” is subjunctive. Normally, we say “I was,” not “I were”: “I was a student at UGA.” If a meeting is over, to end it formally, someone says, “I move that the meeting be adjourned.” “Be” is subjunctive. Normally, we don’t say, “The meeting be adjourned.” Here we use subjunctive because the person in the main clause is trying to get an action in the dependent clause accomplished. This is similar to one of the ways the subjunctive is used in Spanish. Before we get into when we need the subjunctive in Spanish, let’s do a brief review of clauses in English. “Clause” is a group of words with a subject and a verb. An “independent clause” can stand alone; it’s a sentence: Juan lives here. A “dependent clause” cannot stand alone; it is dependent on another clause: Juan lives here because it is close to campus. “Because it is too close to campus” cannot stand alone as a sentence. It is dependent on “Juan lives here.” “Because” is a subordinating conjunction; it is the word that links the dependent and independent clauses. A clause can function in one of three ways: it can be a noun clause, an adjective clause, or an adverb clause: I know that he is here. In this sentence, the clause functions as a noun. Consider the fact that you could say “I know the truth.” There, the word truth is the direct object. In this sentence, “that he is here” is the direct object. Look at this sentence: Juan knows the man that lives here. In this sentence, “that lives here” is an adjective clause. It modifies “man,” tells WHICH man. Now look at this sentence: Juan lives here because it’s close to campus. Remember that adverbs answer when, where, why, how, to what extent. “Because it’s close to campus” is an adverb clause because it answers the question “why.” In this presentation, we’ll be dealing with noun clauses only. In Spanish, noun clauses almost always begin with “que” or “quien,” and 9 times out of 10—or more—it’s “que.” While dealing with the subjunctive in these slide shows, we’re going to deal only with noun clauses that begin with “que,” so remember: if there’s no “que,” you don’t have a noun clause. There are four reasons to use the subjunctive: 1. If the person in the main clause is trying to get the person in the dependent clause to do something or is trying to keep him from doing something, you need the subjunctive in the dependent clause (after the “que”): He suggests that you eat. -- Sugiere que comas. He recommends that you eat. – Recomienda que comas. There’s a difference between the way this idea is usually expressed in English and Spanish. The two sentences above are pretty much the same in the two languages, although you have to remember to use the subjunctive in Spanish. However . . . . . . in most sentences where one person is trying do get another to do something, the sentence structures are different: He wants you to eat. – Quiere que comas. Literally, “He wants that you eat.” He asks you to eat. – Te pide que comas. Literally, “He asks that you eat.” He prohibits you from eating. – Prohíbe que comas. Literally, “He prohibits that you eat.” He permits you to eat. – Permite que comas. Literally, “He permits that you eat.” What you need to see here is that one person is trying to get another person to do (or not do) something. It actually makes more sense in Spanish than in English. What’s the direct object in “He wants you to eat”? “You”? No— he doesn’t want YOU. “To eat”? No—he doesn’t want TO EAT. “He” is doing the wanting, and “you” are doing the eating, so both verbs are conjugated in Spanish. 2. If there’s emotion in the main clause, you need the subjunctive in the dependent clause. Juan is glad that you eat. – Juan se alegra de que comas. Juan is afraid that you eat. – Juan tiene miedo de que comas. Juan likes that you eat. -- A Juan le gusta que comas. It surprises Juan that you eat. – A Juan le sorprende que comas. ****Important note**** You MUST have “que” in all the clauses. “It surprises Juan THAT you eat,” “It surprises Juan IF you eat,” and “It surprises Juan BECAUSE you eat” may sound like they mean the same thing, but the structures are different. “That you eat” is a noun clause; “IF you eat” and “BECAUSE you eat” are adverb clauses, and they follow an entirely different set of rules concerning the subjunctive. “Si” NEVER gets the present subjunctive, no matter what’s in the indicative clause, and “porque” rarely gets the subjunctive. 3. If doubt or denial is expressed in the main clause, you need the subjunctive in the dependent clause. Juan doubts that you eat. – Juan duda que comas. Juan denies that you eat. – Juan niega que comas. Juan doesn’t believe that you eat. – Juan no cree que comas. It isn’t certain that you eat. – No es cierto que comas. It isn’t true that you eat. – No es verdad que comas. It is doubtful that you eat. – Es dudoso que comas. Conversely, if you take away doubt (express certainty or belief), you use the indicative. So if you say the opposite of each of the above sentences, you use the indicative in the dependent clause. Juan doesn’t doubt that you eat. – Juan no duda que comes. Juan doesn’t deny that you eat. – Juan no niega que comes. Juan believes that you eat. – Juan cree que comes. It is certain that you eat. – Es cierto que comes. It is true that you eat. – Es verdad que comes. It isn’t doubtful that you eat. – No es dudoso que comes. 4. When you have (no) es + adjective + que, you need the subjunctive after the “que.” It’s (not) necessary that you eat. – (No) Es necesario que comas. It’s (not) important that you eat. – (No) Es importante que comas. It’s (not) good that you eat. – (No) Es bueno que comas. It’s (not) possible that you eat. – (No) Es posible que comas. There’s an important exception to this rule. Remember rule #3, where you use subjunctive if you have doubt or denial and indicative if you express certainty or belief? Well, if your es + adjective + que expresses certainty or belief, you use indicative: It’s certain that you eat. – Es cierto que comes. It’s true that you eat. – Es verdad que comes. It isn’t doubtful that you eat. – No es dudoso que comes. Click here to go to a practice exercise.