Babson College Accounting 7000 - the Babson College Faculty Web

advertisement

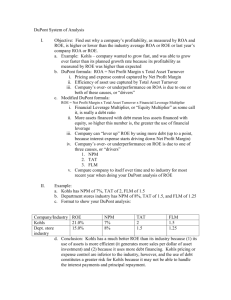

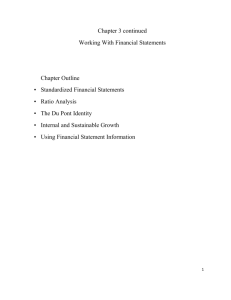

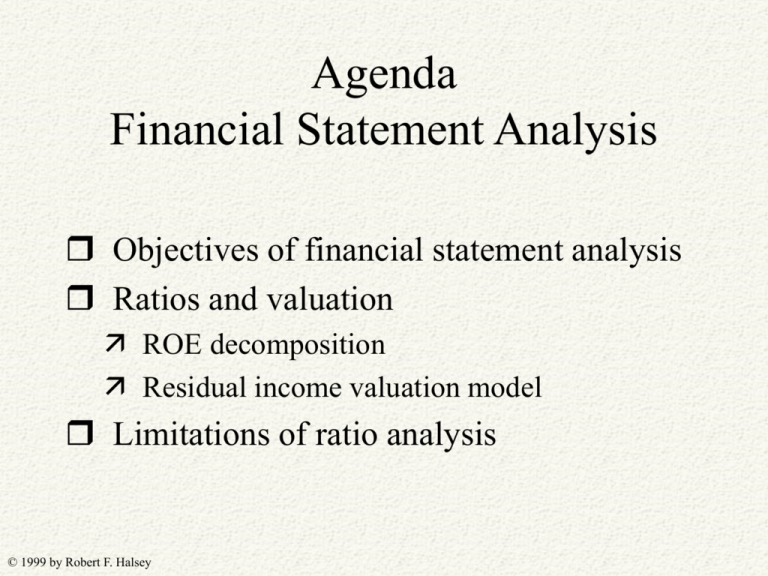

Agenda Financial Statement Analysis Objectives of financial statement analysis Ratios and valuation ROE decomposition Residual income valuation model Limitations of ratio analysis © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Objectives of Financial Reporting Why do we issue financial statements? According to the FASB, the purpose of financial reporting is to provide information that is useful to investors and creditors in order to predict the amount, timing and uncertainty of future cash flows. So, our target audience are investors and creditors, the suppliers of capital to the firm. This is a trickle-down theory. That is, if we supply useful information, then investors and creditors will be able to accurately price company securities (debt and equity) and capital will be efficiently allocated within the economy. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Why do we want to predict the amount, timing and uncertainty of future cash flows? If I know the answer to these three variables, I can price any security. I need to know the amount of the return (cash flows) I will get on my investment, when I will realize this return, and how certain I am of realizing those cash flows. Investors and creditors are not the only parties interested in financial information, of course. There are a number of other users, including suppliers, regulatory and taxing authorities, employees, competitors, and so on. But investors and creditors are our primary audience. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Profitability Analysis The starting point in financial statement analysis is the evaluating the profitability of the company. Any company can increase profitability by increasing the amount of investment it is willing to make in earning assets. So, just looking at the dollar amount of reported profits does not tell us much. We need to evaluate profitability compared to the level of investment. This is done via the return on assets (ROA) ratio © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Return on Assets (ROA) is computed as: Net Income Interest Expense net of tax ROA Average Total Assets This formula relates operating performance to the level of total assets. We add back after tax interest expense to measure profitability before returns to investors and creditors are subtracted (dividends are not an expense so we do not need to add these back) The numerator, thus measures the return to all providers of capital. Our point of view here is the company as a whole, not as an investor or creditor. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Neglecting for the moment the add-back of interest, ROA is approximately to: Sales Net Income ROA Sales Average Total Assets That is, ROA can be decomponsed algebraically into Profitability (Net income / sales) , and Turnover (Sales / Average total assets) We can, then, analyze trends in ROA as follows: Analyze profitability through analysis of gross profit margins and expense control Analyze turnover through analysis of turnover of accounts receivable, inventories and fixed assets © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Another way to look at a company is from the viewpoint of the shareholders. We do this through the return on equity ROE ratio, computed as follows: Net Income Preferred Dividends ROE Average Common Equity Here, the point of view is the common shareholder. Net income is already net of interest paid to creditors and we also subtract the returns to preferred shareholders. The numerator, therefore, is income available to common shareholders. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey ROE can be decomposed in a similar way to ROA. If we ignore the subtraction of dividends, ROA is approximately equal to, Avg T A ROE * * Avg Equity Sales AvgT A NI Sales PM * T urnover * Fin. Leverage ROA * Financial leverage ROE is, therefore, roughly equivalent to ROA multiplied by the firm’s financial leverage. Company managers can increase return on equity by utilizing more borrowed capital in their businesses. This debt, however, comes at a price. The firm is more risky as a result since failure to make the required debt payments can result in bankruptcy. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey ROE can also be expressed as follows: ROE = ROA + (FLEV * Spread) where FLEV is financial leverage and Spread = ROA – Interest rate on debt This points out clearly the fact that firms can increase ROE by taking more financial risk in the form of debt. This is true so long as the return on assets purchased with the debt is greater than the interest rate on the debt. This concept is called “trading on the equity.” © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey But, why should ROE be the focus of our analysis? The answer lies in modern valuation theory which postulates that firm value can be expressed by the following equation: P = BV + PV(expected RI) where, P = stock price BV = book value of stockholder’s equity PV denotes present value RI = residual income This is the Residual Income Valuation Model. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Residual income (RI) is defined as, RI = I - r * BV where I = reported net income r = cost of equity capital (the return the company’s shareholders require on their investment) BV = beginning book value Residual income, then measures the excess (deficiency) of profits compared with expected levels of profitability © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Residual income can also be expressed as follows: RI = I - r * BV = (ROE - r) * BV where, ROE=I/BV So, Shareholder value is increased as residual income increases and residual income increases as ROE increases. That is why we focus on ROE. Also, note that a company can increase shareholder value by: Increasing profitability while holding investment constant Maintaining profitability with a lower investment base Some combination of the two. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey These observations have the following implications for managers: Performance evaluation should be based on both reported profits and the level of investment entrusted to the manager (whether at the divisional level of the firm as a whole) Company managers should invest additional capital in those divisions that can use it effectively and re-deploy capital away from those that can’t. This concept is currently marketed by business consultants under the name Economic Value Added (EVA™) that you might have read about in the financial press. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey One of the most famous methods of disaggregating ROE into its components is the DuPont method of analysis: Profit Margin Gross Profit /Operating Exp. X Accounts receivable turn ROE = TA Turnover X Fin Leverage © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Inventory turn Fixed asset turn Profit margin The starting point in the analysis is the evaluation of profitability. We look at two primary ratios: 1) Gross Profit Margin = Gross Profit / Sales – 2) This measures ability of the firm to mark up the cost of its products or services into market prices Operating expense percentage = SG&A expenses / Sales Where SG&A are selling, general and administrative expenses (overhead). – This measures how well the firm is able to control its operating expenses © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Turnover Ratios are the second step: • Accounts Receivable Turnover ratio = sales / average accounts receivable – Indicator of collectability of accounts and effectiveness of working capital management • Inventory Turnover ratio = cost of goods sold / average inventory – Indicator of salability of inventory and effectiveness of working capital management • Plant Asset Turnover ratio = sales / average plant assets – Indicator of effective utilization of assets © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey These three ratios give us clues into the amount of investment that is required to support a given level of sales. Companies that can generate sales volume with minimal investment will yield higher ROE’s than those that cannot. Receivable and inventory turnover ratios also give us insight into the “quality” of those assets. As accounts receivables take longer to collect (their turnover rate declines), the risk of uncollectability increases. Also, as inventories sit on the shelf for longer periods of time (theur turnover decreases) there is a greater risk of obsolescence, damage, etc which can reduce their market value. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The last area of analysis is the firm’s leverage. Here we are concerned with two possibilities: Is the firm leveraging itself enough? Firms can increase ROE and, thus, stock price by increasing financial leverage. Operating at too low a level of leverage does not effectively utilize the firm’s equity and will not maximize shareholder value. Utilizing too much debt increases the risk of bankruptcy. As this risk increases, shareholders will demand a higher expected return. This will limit the number of possible projects the firm can invest in since shareholder value is increased only so long as ROA > r (the required return shareholders expect). If the firm can’t grow, its stock price sill suffer. This suggests a theoretical optimum amount of financial leverage – just enough to that shareholder equity is maximized, but not too much so that the risk of bankruptcy increases. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey So, how do we measure whether the firm is taking on enough debt? We can look at its competitors. Industries will find an equilibrium level of financial leverage for the type of business they are in. If the firm is operating at lower levels of leverage than others in its industry, perhaps this is an indication that its shareholder’s equity is not being effectively utilized. And how do we assess the risk of bankruptcy for firms operating with more financial leverage? The text describes several ratios designed to give us clues whether the level of financial leverage is too high. These are under the general heading of Long-term liquidity (solvency) risk measures: –Debt ratio (Debt/Total Assets or Debt/Equity) –Cash flow from operations to total liabilities –Times Interest Earned ratio (EBIT / I) © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey In addition to measuring the the ability of the firm to make payments on its long-term debt, we are also interested in it’s short-term debt paying ability. This is called liquidity analysis. Liquidity analysis is generally performed with three ratios described in the text: Current ratio = current assets / current liabilities Quick ratio = quick assets / current liabilities Cash flow from operations to current liabilities All of these are designed to give us a feel for the degree to which the firm is liquid. That is, does is have enough cash to meet its obligations maturing in the near term or does it have the ability to raise cash quickly from assets or operations. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Return on Common Equity Decomposition International Business Machines Corporation IBM provides a good example of the ROE decomposition: During 94-97, its ROE increased dramatically, as did its stock price. All areas increased – turnover, margins and leverage. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Result Return on Equity Fy94 .14 Fy95 .18 Fy96 .25 Fy97 .30 Determinants TA Turnover Fy94 .79 Fy95 .89 Fy96 .94 Fy97 .96 A/R Turn Fy94 3.13 Fy95 3.20 Fy96 3.26 Fy97 3.34 Inv Turn Fy94 4.98 Fy95 5.94 Fy96 6.85 Fy97 7.97 Profit Margin Fy94 .05 Fy95 .06 Fy96 .07 Fy97 .08 Gross profit % Fy94 .46 Fy95 .48 Fy96 .45 Fy97 .44 OP Margin Fy94 .08 Fy95 .14 Fy96 .12 Fy97 .12 TA/TE Fy94 3.46 Fy95 3.58 Fy96 3.75 Fy97 4.11 Market Price Fy94 $ 36 Fy95 $ 46 Fy97 $ 76 Fy97 $105 Details FA Turn Fy94 3.75 Fy95 4.33 Fy96 4.47 Fy97 4.39 As another example of the ROE decomposition analysis, look at the ratios relating to Dell and Compaq. Dell’s ROE ROE PROF MARG TA TURN DEBT/TA increased dramatically during COMPAQ the period while 92 10.8 5.2 1.4 0.0 Compaq’s was flat 93 19.8 6.4 2.0 0.0 94 95 96 97 27.4 19.0 24.4 23.8 8.0 5.3 7.3 7.5 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.0 4.9 3.8 2.9 0.0 92 93 94 95 96 97 31.6 -9.4 25.0 32.0 59.7 89.9 5.0 -1.2 4.3 5.1 6.8 7.7 2.7 2.8 2.5 2.8 3.0 3.4 6.1 8.8 7.1 8.1 1.5 3.8 DELL © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Although their profit margins were similar, Dell’s asset turnover was considerably higher (due primarily to better inventory management) And its leverage is higher. Finally, there are several factors which limit the effectiveness of financial statement Analysis: Firms have differing accounting principles, estimates, and levels of conservatism. So, comparisons can be difficult. Even within the same firm, its characteristics can change over time due to mergers, new products, management changes, etc. Also, if quarterly data is analyzed, analysts must adjust for seasonal changes. Conglomerates are difficult to analyze. They are, in essence, a blend of many different firms operating in many different industries. And also, it is sometimes difficult to compare these firms with industry averages since they operate across industry lines. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey It is very important to remember that ratios are not an end, but a starting point to further probing. The fact that a ratio increased or decreased is not interesting. We must, then, attempt to discover why this change took place. That is, what were the business factors that led to the change manifested in the financial statements? Remember, the reality is the company itself, not its financial statements. Does it have the right products at the right price? Does it have the right amount of investment in order to conduct its business? Is it utilizing the right amount of financial leverage? The amounts reported in the financial statements are a representation of what is really happening with the business. The task of the analyst is to understand the business factors that give rise to the reported figures. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The End © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey