Ecological Succession

advertisement

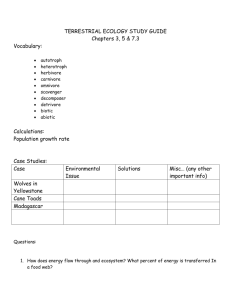

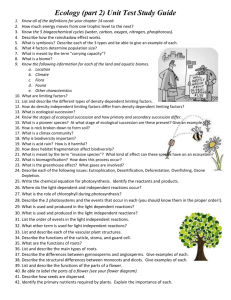

Ecological Succession • Ecological succession is the gradual process by which ecosystems change and develop over time. • For example, a bare patch of ground will not stay bare. It will rapidly be colonized by a variety of plants. A recently cleared patch of ground (in Britain). The same ground 2 years later, now covered in grasses and low flowering plants. What is ecological succession? • "Ecological succession" is the observed process of change in the species structure of an ecological community over time. Within any community some species may become less abundant over some time interval, or they may even vanish from the ecosystem altogether. Similarly, over some time interval, other species within the community may become more abundant, or new species may even invade into the community from adjacent ecosystems. This observed change over time in what is living in a particular ecosystem is "ecological succession". Pioneer Species The bare ground conditions favor pioneer plant species which are the first plants to occupy these areas. These are often species which grow best where there is little competition for space and resources. The pioneer community is formed of species able to survive under hostile environments. The presence of these species modifies the microenvironment generating changes in abiotic and biotic factors of the ecosystem undergoing formation. Therefore they open the way to other species to establish in the place by the creation of new potential ecological niches. Two Types of Succession • Primary succession is the changing sequence of communities from the first biological occupation of a place where previously there were no living beings. For example, the colonization and the following succession of communities on a bare rock. • Secondary succession is the changing sequence of communities from the substitution of a community by a new one. For example, the ecological succession of the invasion of plants and animals in an abandoned crop or land. Which type of succession is pictured above? Why does ecological succession occur? • • Every species has a set of environmental conditions under which it will grow and reproduce most optimally. In a given ecosystem, and under that ecosystem's set of environmental conditions, those species that can grow the most efficiently and produce the most viable offspring will become the most abundant organisms. As long as the ecosystem's set of environmental conditions remains constant, those species optimally adapted to those conditions will flourish. The "engine" of succession, the cause of ecosystem change, is the impact of established species have upon their own environments. A consequence of living is the sometimes subtle and sometimes overt alteration of one's own environment. The original environment may have been optimal for the first species of plant or animal, but the newly altered environment is often optimal for some other species of plant or animal. Under the changed conditions of the environment, the previously dominant species may fail and another species may become ascendant. Ecological succession may also occur when the conditions of an environment suddenly and drastically change. A forest fires, wind storms, and human activities like agriculture all greatly alter the conditions of an environment. These massive forces may also destroy species and thus alter the dynamics of the ecological community triggering a scramble for dominance among the species still present. How are humans affected by succession? • Ecological succession is a force of nature. Ecosystems are in a constant process of change and re-structuring. To appreciate how ecological succession affects humans and also to begin to appreciate the incredible time and monetary cost of ecological succession, one only has to visualize a freshly tilled garden plot. Clearing the land for the garden and preparing the soil for planting represents a major external event that radically re-structures and disrupts a previously stabilized ecosystem. The disturbed ecosystem will immediately begin a process of ecological succession. Plant species adapted to the sunny conditions and the broken soil will rapidly invade the site and will become quickly and densely established. These invading plants are what we call "weeds". Now "weeds" have very important ecological roles and functions but weeds also compete with the garden plants for nutrients, water and physical space. If left unattended, a garden will quickly become a weed patch in which the weakly competitive garden plants are choked out and destroyed by the robustly productive weeds. A gardener's only course of action is to spend a great deal of time and energy weeding the garden. This energy input is directly proportional to the "energy" inherent in the force of ecological succession. If you extrapolate this very small scale scenario to all of the agricultural fields and systems on Earth and visualize all of the activities of all of the farmers and gardeners who are growing our foods, you begin to get an idea of the immense cost in terms of time, fuel, herbicides and pesticides that humans pay every growing season because of the force of ecological succession. Does succession ever stop? • There is a concept in ecological succession called the "climax" community. The climax community represents a stable end product of the successional sequence. Its apparent species structure and composition will not appreciably change over observable time. To this degree, we could say that ecological succession has "stopped". We must recognize, however, that any ecosystem, no matter how inherently stable and persistent, could be subject to massive external disruptive forces (like fires and storms) that could re-set and re-trigger the successional process. As long as these random and potentially catastrophic events are possible, it is not absolutely accurate to say that succession has stopped. Also, over long periods of time ("geological time") the climate conditions and other fundamental aspects of an ecosystem change. These geological time scale changes are not observable in our "ecological" time, but their fundamental existence and historical reality cannot be disputed. No ecosystem, then, has existed or will exist unchanged or unchanging over a geological time scale. These photos show __________ succession, the development of a community where none was before. The images were taken at Acadia National Park in Maine. The first to appear on the bare rock are lichens and algae. These secrete acids which begin to extract nutrients from the rock and which form tiny cracks which are widened by freezing and thawing. As the cracks widen they trap enough organic material and moisture for mosses to take hold. Larger cracks have enough soil to support grasses and small shrubs. The largest cracks come together to form small basins where trees can take root, although the tree in the photo below didn't make it too long; perhaps a drought exhausted the water in the small basin. However, in the background the climax coniferous forest is visible where enough soil has accumulated to support the trees. A successional story takes root on the west coast at Mt. Rainier in Washington. Once again, the lichens are the first to appear (although they are hard to spot here). More obvious are the mosses, grasses and small plants like flowers. Each stage accumulates soil and organic material that facilitates the growth of the next stage. On this mountainside, the coniferous forest is the climax community. Secondary Succession - Lake Succession: In this image, a former bog in Maine has almost completely filled. A former lake, formed originally when a large piece of ice broke off a retreating glacier, is now well along the transition to dry land. These kettlehole lakes often support an extensive mat of floating vegetation. The bog in the picture above left (from Minnesota) is a good example. You can still see open water, but a mat of floating vegetation (the material between the foreground and the open water) has developed. Fire and Succession: Fire plays a complex role in succession. Usually, a fire stops the progression of succession and sets the stage for new, secondary succession as plants take root and grow in the soil enriched by the mineral ashes of their predecessors. In some cases, however, fire plays an even more important role. It maintains the climax community by removing competitors that would otherwise move the climax to a different type of community. Two examples are shown here. The shrubland habitat of southern California is maintained by fire, which eliminates large trees. The pictures above and to the left show a large fire burning a hillside; any trees that had been growing there would be killed and the shrubs and other plants adapted to fire would spring back quickly and reclaim the habitat. Above left, an area at the Archbold Biological Station, just a few days after it was burned. The plant in the foreground is a palmetto; after the fire it was able to resprout quickly from the prostrate stalk, which has a thick covering which is able to resist the fire. The picture below shows an area on the other side of the road which had not burned for a long time, and which is full of small trees such as scrub oaks and scrub hickories. In the drought year of 1988, huge fires swept through Yellowstone National Park (above and left). After years of fire suppression in the park, the forest floor was loaded with potential fuel, and the resulting fire burned hotter than it would have if more frequent, patchy fires had been allowed to take their natural course. The pictures above were taken in 1999; 11 years after the fires. The slow regrowth is in part due to the cold temperatures there. To the left, a pine sapling struggles to regrow after the fire. In Yellowstone, the fires moved the community away from its climax and set secondary succession into motion. Below: since the Yellowstone fires of 1988, the National Park Service has adopted more enlightened fire practices. Among these are prescribed burning. The Park Service actually sets small fires to approximate the frequency of burning that would occur under natural conditions. This creates smaller, patchier fires that kill only the species least tolerant of fires, and tend to increase overall diversity as burned and unburned areas are in close proximity. The pictures below are from Everglades National Park in Florida. The everglades are a fire-dependent ecosystem; spring rains come in the form of thunderstorms and lightning strikes any trees that are growing there. The resulting fire kills the trees and allows the native sedges like sawgrass to reclaim the landscape. Here, fire maintains an unstable climax. Clear cutting: When forests are clear-cut, secondary succession begins on the deforested plots. To speed the process, and to ensure that the resulting forest will be the same age and easy to harvest, timber companies usually replant the forest. This, however, results in a forest of trees which are often genetically very similar, and of course, of the same age. This creates a patchwork landscape as you can see in these pictures. Because these forests do not retain any of the old trees which provide food and nest sites for many animals, they are not very diverse in terms of wildlife either. Wildlife depends on a diversity of trees which themselves vary in age from saplings to mature and even dead trees. Above: The valley you see in the photo was created by a retreating glacier (it's camera shy and hiding behind the bend in the valley). Initially, the steep slopes are subject to slides, and not much will be able to grow there. As the land stabilizes, however, succession will begin to take hold and, if the climate does not cool and allow the glacier to grow again, the forests will cover the slopes. Old-field Succession: The abandoned pasture is slowly reverting to forest. Grasses are gradually replaced by other perennials such as milkweeds, goldenrod, and shrubs. Next come small trees adapted to this habitat. These would include sassafras, hawthorns and the like. Larger trees such as oaks, maples, hickories and eventually beeches will begin to come into the picture, and eventually a mature forest such as the old-growth forest will come into being after hundreds of years. Note the diversity of tree sizes in the mature forest. In 1980, Mt. St. Helens in Washington erupted, essentially destroying all life in a large blast zone. Trees were killed (above left) and the ground was covered with ash (left). In some places, such as the protected side of a knob (below left), while the mature trees were killed the soil was not sterilized as it was in other places. This meant that seeds could germinate and begin to replace the forest more rapidly than was possible in areas where no seeds survived. The photo to the left shows a lava flow from Costa Rica. This lava was deposited during an eruption in 1992, 15 years before the picture was taken. As you can see, plant life is trying to re-establish itself on the lava flow, which is a very inhospitable environment as it is hot and dry, with little soil. On the other hand, the soil that is present is rich in nutrients. Because the existing community and the soil are so thoroughly destroyed by volcanic eruptions the succession that proceeds is called Primary Succession (as opposed to the secondary succession occurring after a forest fire). Below Left: Orchids are actually among the plants best adapted to live in such extreme environments as lava flows. Long growing seasons and plenty of rain help accelerate succession in Costa Rica.