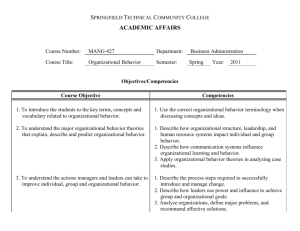

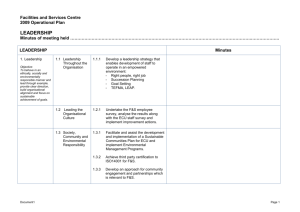

Compromise model

advertisement

Principles of Comparative Research Some review slides Robert Thomson Some themes that run through the course • The distinction between qualitative and quantitative research is stylistic • Empirical research of all types should be theory-driven • Develop theories that explain as much as possible with as little as possible • Report uncertainty • Develop rival hypotheses A social scientist should always be able to answer: “How would you know if you were wrong?” Defining social scientific research • Science is a set of principles, whose application is not restricted to a particular empirically defined subject area • The ultimate goal is causal inference • Procedures are public • Conclusions are uncertain What are the boundaries within which the scientific method applies in political science? • To both basic and applied research that is empirical • Not directly to non empirical (purely theoretical, sometimes normative) research – But even in these traditions, researchers refer to facts about and relationships found in politics Causal inference • Theories give explanations of classes of phenomena (e.g. the occurrence of wars, the duration of governments, choice of parties by voters) • Theories state causal relationships between variables • Theories simplify • Inference involves moving from observed to unobserved cases (e.g. from samples of respondents to entire populations) Towards causal inference • Draw out observable implications of the theory • Select cases for study that allow you to move beyond these particular observations - this often means ensuring they are representative • Pay careful attention to accurate description Public procedures • A social enterprise • Replicable – The derivation of hypotheses and predictions from a theory – The measurement of concepts – The analysis of relationships among variables Uncertainty Due to: • making inferences from observed to unobserved cases • the complexity of social phenomena – multiple causes – rudimentary theory • measurement error • rival theories Research is never finished Evaluating research • This implies that, at a minimum, social scientific research should: – lead to valid causal inferences – contain clear reports of procedure – report sources and levels of uncertainty • Contrast this with: “Like any creative work, research should be evaluated subjectively, according to informal and rather flexible criteria” (Shively 2002: 10) This applies to both quantitative and qualitative research • Quantitative social research – Abstraction from particular events – Sometimes applies formal theory – Numerical measurement of concepts • Qualitative social research – Smaller number of cases, usually important in their own right – Rich descriptive approach to data gathering and analysis Political science often combines quantitative and qualitative methods • E.g. – Government efficiency in Italy (Putman 1993) – International economic cooperation (Martin 1992) – Decision-making in the European Union (Hix 2006) – Democratic performance/ pledge fulfilment in various countries (e.g. Mansergh 2005; Thomson 2001) The main components of a research design A dynamic process within a stable set of rules of inquiry • Research questions • Theory • Deciding how and what to observe – Measurement – Case selection • Analysing data Research questions • Where do they come from? – “there is no such thing as a logical method of having new ideas… Discovery contains an ‘irrational element’, or a ‘creative intuition’” (Karl Popper 1968 32) • Unlike other parts of the research design, little to no formalised procedures “Real reasons” for choosing a particular question • Personal motives – Membership of/affinity with the group affected by the topic – To help some group achieve its goals – Curiosity • Neither necessary nor sufficient • The scientific community does not care what we think, only what we can demonstrate – Contrast this with Blaikie (2000: 48): “It is important for researchers to articulate their motives for undertaking a research project, as different motives may require different research design decisions.” Guidelines for selecting questions • Social and scientific relevance • Social relevance – “important” in the real world • Scientific relevance – A contribution to a scientific body of knowledge Types of scientific relevance • A hypothesis that is presented as being important but has not yet been examined systematically • An accepted hypothesis believed to be false • (Apparently) contradictory hypotheses from different theories • (Apparently) contradictory findings • A new test of an old theory • Transfer of theories from other (sub) disciplines • Replication Types of research questions • Descriptive and explanatory – What (Descriptive) – Why (Explanatory) – How questions (Interventionist) (Blaikie 2000) • Relation to research objectives – – – – – – – Exploration Description Understanding Explanation Prediction Change Evaluation • Causal inference as the ultimate scientific objective? Blaikie’s procedure for identifying questions – Write down every question you can think of – Review the questions (order and prioritise) – Separate what, why and how questions (reformulate so you can put them into these boxes) – Expose assumptions – Examine scope (practicalities) – Separate major and subsidiary questions – Is each question necessary? • Does any researcher do it like this? Graham Allison & Philip Zelikow (1999) Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis 2nd. Ed. • Stated research questions – Why did the Soviet Union place strategic offensive missiles in Cuba? – Why did the US respond with a naval quarantine of Soviet shipments to Cuba? – Why were the missiles withdrawn? – What are the lessons of the missile crisis? Allison’s general argument • We think about problems of foreign and military policy in terms of largely implicit conceptual models • The Rational Actor Model dominates • Two other models – the organisational behaviour model and the governmental politics model – provide improved explanations Allison’s (implicit) overarching research question • What is the relative power of three competing theories in explaining the Cuban missile crisis? – Rational Actor Model – Organisational Behaviour Model – Governmental Politics Model Specific research questions associated with each theory • Rational Actor questions included – What were the objective (or perceived) costs and benefits of the available options? – What were the states’ best choices in this situation? • Organisational Behaviour questions included – Of what organisations did the governments consist? – What capabilities and constraints did these organisations’ “standard operating procedures” create in generating options for action? Specific questions cont. • Governmental Politics questions included – Who played? Whose views and values counted in shaping the choices for actions? – What factors accounted for each player’s impact on the choices for action? George Tsebelis (2002) Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work • Presents and tests a general theory of political institutions • Examines the consequences of variations in the numbers and locations of veto players in political systems • Main focus on policy stability – causes and consequences Veto players and policy stability The winset SQ1 A Winset of SQ C B (Intersection of indifference curves) Veto players and policy stability The core SQ1 A Core (within triangle) SQ2 B C No winset of SQ2 Tsebelis’ main research questions • How do veto players affect policy stability? • How does policy stability affect political outcomes such as: – The extent to which governments control the agenda – Government duration – Public expenditure – Bureaucratic independence – Judicial independence – Legislative outcomes in the European Union? What are causal theories? • A reasoned answer to an explanatory question • Identifies the explanatory variables, variation in which causes change in the dependent variable – Usually involving a set of assumptions, and descriptive and explanatory hypotheses • No theory without evidence What is causation? • A theoretical construct • Implies a counter-factual thought experiment – E.g. what if another party had entered government. Would public expenditure be different? – What should you hold constant in your thought experiment? • The Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference – We cannot observe causation directly Inferences about causal effects • Based on observable variation across different units or cases • Requires – Comparability – Unit homogeneity or constant causal effects Are there other types of causation? • Causal mechanisms / process tracing – The processes through which variation in an IV causes variation in DV • Multiple causality – Different IVs may lead to the same changes in DV • Asymmetric causality – Increase in value of IV may not have the same size of effect as a decrease of IV of the same magnitude What does a good theory look like? • Falsifiable – Could be wrong • Internally consistent – Don’t contradict themselves • Concrete – Contain clearly defined concepts • Broad in scope – Explain lots of things Falsifiable • Avoid tautologies – E.g. some applications of the concept of national interest in explaining foreign policy decisions • Distinct from Popper’s use of the term • Use both confirming and disconfirming evidence to gauge theory’s scope Internally consistent • Contradictory hypotheses prove a theory wrong without evidence • Formal models are used to provide consistency – Mathematics and the study of political systems – Abstract from complexity of reality – Ignore other relevant IVs • At what cost? – Exclusion of other relevant IVs – Accessibility Concrete • • • • Avoid vaguely defined concepts Think ahead to operationalisation Avoid reification What this does not mean – Studying only phenomena that can be observed directly – Limiting scope unduly Broad in scope • Explain as much as possible with as little as possible • Push the boundaries of the theory’s applicability • Tempered by – Need to be concrete – The fact that most social science theories are conditional (only sometimes true) Allison’s Model I: Rational Actor Model • Basic unit of analysis: governmental action as choice • Main concepts: – Unified “national” actor – Action as rational choice • • • • Objectives Options Consequences Choice Rational Actor Model cont. • Dominant inference pattern – Finding purposes that are served by the action being explained • General proposition – Increase in perceived costs of an alternative reduce the likelihood of that action being chosen • Evidence – Relates to objectives, options and perceived consequences – Naïve applications in danger of tautology Allison’s Model II: Orgnisational Behaviour Model • Basic unit of analysis: Governmental action as organisational output • Main concepts: – Organisational actors – Factored problems and fractionated power – Organisational objectives, capacities – Organisational routines and standard operating proceduures Organisational Behaviour Model cont. • Dominant inference pattern – Uncover the capacities and organisational routines that produced the outputs (policy actions) in question • General propositions include – Existing organisational capabilities influence government choice – Organisational priorities shape organisational implementation • Evidence – On the organisations involved An exchange model of political bargaining Stokman & Van Oosten (1994) A Ot0 D Ot1 B C Issue 1 A Ot1 B Ot0 C D Issue 2 Potential exchange partners if: Issue 1 Left Right Left A C Right B D Issue 2 sA1/sA2 sD1/sD2 A model of the consultation procedure Adapted from Garret and Tsebelis 1999 SQ 1 2 3 Pivotal player QMV 4 5 6 Predicted Outcome QMV 7 COM Compromise model 200 180 160 140 Power / 120 Effective 100 80 power 60 40 20 0 Predicted outcome of model 0 20 40 Power Effective power 60 80 Issue continuum / positions 100 The Compromise Model Oa = ( xia cia sia ) / ( cia sia ) Oa : Prediction of compromise model on issue a xia : Position of actor i on issue a cia : Capabilities of actor i on issue a sia : Salience actor i attaches to issue a Illustration of model predictions A fisheries regulation (CNS/1998/347) Issue 1: Scrap build penalty: How many tones of old fishing vessels need to be scrapped to qualify for EU funding for fleet renewal? Procedure XM 0 21 BE, EP, FI, FR, DE, EL, IE, IT, PT, ES, SE 0: One to one. Reference point and OUTCOME Compromise model 36 COM 50: Scrap 115 tones of old ship for every 100 tones of new AT, DK, UK 90: 130 old for 100 new 100: 150180 old for 100 new Issue 2: Linkage. To what extent should funding be linked to MAGP Compromise Procedure targets? NL 0: No linkage reference point EP, FR, IE, IT, ES 40: limited linkage model 68 BE, AT, DK, FI, EL, PT DK, SE, UK 80 70: linked to annual objectives OUTCOME XM 86 COM 100: Linked to annual and final objectives