California - Health | Wolters Kluwer Law & Business

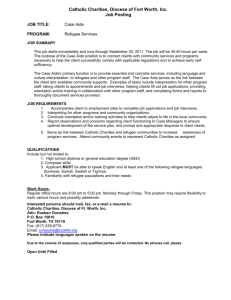

advertisement