Terms PPT

advertisement

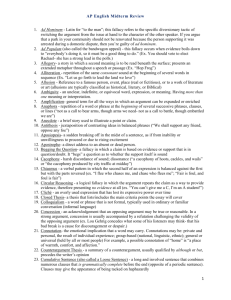

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVYzxxg KXTY Persuasion per·suade to prevail on (a person) to do something, as by advising or urging: We could not persuade him to wait. to induce to believe by appealing to reason or understanding; convince: to persuade the judge of the prisoner's innocence Manipulation ma·nip·u·late to manage or influence skillfully, esp. in an unfair manner: to manipulate people's feelings. to adapt or change (accounts, figures, etc.) to suit one's purpose or advantage. http://dictionary.reference. com What examples of persuasion do you see? How is one person manipulating the other? How is the persuasion and manipulation affecting choice? How do authors persuade us of their point of view? How do we evaluate the quality of an argument? How do we spot logical fallacies? How do we discern tone and how does the correct reading of tone change our understanding of the author’s purpose? ◦ It’s all around us – in conversations, in movies, in advertisements and books ◦ Aristotle: “Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” ◦ Rhetoric is the art of language – of using its resources effectively and usually with a certain goal in mind. Resources include: word choice, any and all figures of speech, and structure of composition. ◦ The Rhetorical Triangle: Subject, Audience, Speaker’s Persona The Rhetorical Triangle Speaker Audience Subject When considering the subject, the writer/speaker evaluates what he/she already knows and needs to know, investigates perspectives, and determines the kinds of evidence or proofs that seem most useful. When considering the audience, the writer or speaker speculates about the reader’s expectations, knowledge and disposition with regard to the subject. Speakers/writers use their experiences and observations Use who they are, what they know and feel, and what they’ve seen and done to find their attitudes toward a subject and their understanding of a reader. How we, the reader, characterize the speaker based upon their language. Persona – the character the speaker creates as he or she writes or speaks - voice There are two other elements of the rhetorical situation - the context in which writing or speaking occurs and the emerging aim or purpose that underlies many of the writer’s decisions. Rhetoric is situational – it has context – the occasion or the time and place it was written or spoken. Rhetoric has a purpose – a goal that the speaker or writer wants to achieve. Logos Writers appeal to a reader’s sense of logos when they offer clear, reasonable premises and proofs, when they develop ideas with appropriate details; these details and proofs help the readers to follow the progression of ideas. Writers use logos to inform speaker’s decisions and readers’ responses Ethos Writers use ethos when they demonstrate that they are credible, good-willed, and knowledgeable about their subjects Writers connect their thinking to reader’s own ethical or moral beliefs in that you, the reader, believe and trust this writer to be credible, goodwilled, and knowledgeable, and want to continue listening. Pathos When writers draw on the emotions and interests of readers, and highlight them, they use pathos. Use of personal stories or observations to provoke readers’ sympathetic reaction. Figurative language is often used to heighten the emotional connections readers make to the subject. "Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth. I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans. "Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn't consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I'm lucky. Who wouldn't consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball's greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Sure, I'm lucky. "When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift - that's something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies - that's something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter that's something. When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body - it's a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed - that's the finest I know. "So I close in saying that I may have had a tough break, but I have an awful lot to live for." Context & Purpose: Speaker, Audience, Subject: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qswig8dcEAY The Appeals: Logos, Pathos, Ethos: The goal of an argument is to strengthen or weaken rather than overturn one’s convictions/thoughts/beliefs An argument is… o a way of establishing and testing out ideas o an activity that helps us form our beliefs and determine our actions o a process of discussion and deliberation rather than a contest of opposites Rhetoric is the way to connect intentions with responses, the way to reconcile readers and writers. Investigating how readers perceive intentions exposes where and how communication happens or is lost. Intention is sometimes embodied in a thesis statement – but intention is carried out throughout a piece and it often changes. Speaker Occasion Audience Purpose Subject Tone An acronym for a series of questions that students must first ask themselves, and then answer, as they begin to plan their essays Who is the Speaker? ◦ The voice that tells the story –Who are you? What details will you reveal? Why is it important that the audience know who you are? What is the Occasion? o The time and place of the piece: the context that prompted the writing – How does your knowledge of the larger occasion and the immediate occasion affect what you are writing about? o Larger Occasion – an environment of ideas, attitudes, and emotions that swirl around a broad issue – the bigger picture o Immediate Occasion – an event or situation that catches the writer’s attention and triggers a response. Who is the Audience? o The group of readers to whom this piece is directed – What are the characteristics of this group? How are they related to you? Why are you addressing them? What is the Purpose? o The reason behind the text – “What do I want my audience to think or do as a result of reading my text?” Explain yourself – what you hope to accomplish by this expression of opinion. How would you like your audience to respond? What is the Subject? o Students should be able to state the focus on the intended task – What are you talking about? What is the Tone? o The attitude of the author –How will your attitude enhance the effectiveness of your piece? Students must learn to convey tone in their: Diction – choice of words Syntax – sentence construction Figurative Language – imagery, metaphors, similes, and other figurative language (involves rhetorical device) Denotation: the explicit or direct meaning of a word Connotation: the associated or secondary meaning of a word Jolliffe’s Rhetorical Framework Design Exigence (a need or demand) Rhetorical Situation Audience Purpose Logos Appeals Ethos Pathos Organization/Structure/Form Diction Syntax Imagery Surface Features Figurative Language Imagery – those words, those details that create vivid images; based within the five senses Metaphor- comparison of two unlike objects Simile – comparison of two unlike objects using like or as Alliteration – repetition of initial consonant sounds (consonance = repetition of consonants; assonance = repetition of vowels) “While I nodded nearly napping,” -Edgar Allen Poe, “The Raven” Allusion – a reference, explicit or implicit, to something in previous literature and history • “The girl's love of diamonds was her Achilles’ heel.” http://www.buzzle.com/articles/allusion-examples.html Anaphora – the repetition of words, phrases, or clauses in successive lines, stanzas, or paragraphs. “It’s the story of students who sat where you sit 250 years ago, and went on to wage a revolution and they founded this nation. Young people. Students who sat where you sit 75 years ago who overcame a Depression and won a world war; who fought for civil rights and put a man on the moon. Students who sat where you sit 20 years ago who founded Google and Twitter and Facebook… -Barack Obama, National Address to America’s School Children, 2009 Counterargument – to anticipate objections or opposing views; a way to appeal to logos Concede – in acknowledging a counterargument you agree (concede) that an opposing argument may be true, but then you… Refute – to prove to be false - the validity of all or part of the argument. This concession or refutation actually strengthens your argument; it appeals to logos by demonstrating that you have considered your subject carefully before making your argument. Parallel Structure – means using the same pattern of words to show that two or more ideas have the same level of importance. ◦ The usual way: to join parallel phrases/clauses with the use of coordinating conjunctions “and” or “or” Mary likes hiking, swimming, and bicycling -The Owl, Purdue University Rhetorical Question – a statement constructed as a question that is not intended to be answered ◦ “Isn’t it a bit unnerving that doctors call what they do ‘practice’?” George Carlin, yahoo.com The Imperative – the command form of the verb Listen! Go! Wait! Analogy – a kind of extended metaphor or long simile in which an explicit comparison is made between two things (events, people, etc.) for the purpose of furthering a line of reason or drawing an inference In other words – an analogy relates difficult issues to something familiar "Remember this, ladies and gentlemen. It's an old phrase, basically anonymous -- that politicians are a lot like diapers: They should be changed frequently and for the same reason. Keep that in mind next time you vote. Good night. -- delivered by Robin Williams (from the movie Man of the Year) If-then clause – a device used to emphasize the potential consequences of certain actions - usually phrased as a warning or to express potentially negative consequences For example: If you do not clean your room immediately , then you will not be going out this weekend. Onomatopoeia: ◦ 1. the formation of words whose sound is imitative of the sound of the noise or action designated, such as hiss, buzz, and bang ◦ 2. the use of such words for poetic or rhetorical effect ◦ * From the Greek: “to make words” http://dictionary.reference.com Hyperbole/exaggeration ◦ 1. obvious and intentional exaggeration. ◦ 2. an extravagant statement or figure of speech not intended to be taken literally, as “to wait an eternity.” http://dictionary.reference.com Understatement: ◦ the act or an instance of stating something in restrained terms, or as less than it is ◦ A form of irony in which something is intentionally represented as less than it is: “Hank Aaron was a pretty good ball player.” http://dictionary.reference.com To show or indicate beforehand; prefigure: Political upheavals foreshadowed war. http://dictionary.reference.com Chronological: The story’s key events are presented as they occur “A flashback is a narrative technique that allows a writer to present past events during current events, in order to provide background for the current narration. By giving material that occurred prior to the present event, the writer provides the reader with insight into a character's motivation and or background to a conflict. This is done by various methods, narration, dream sequences, and memories” (Canada). http://www.courses.vcu.edu/ENG-jeh/BeginningReporting/Writing/storystructure.htm http://www.uncp.edu/home/canada/work/allam/general/glossary.htm 1. a position from which someone or something is observed (the manner something is considered or evaluated) - from the point of view of a doctor. 2. an opinion, attitude, or judgment - He refuses to change his point of view in the matter. 3. the position of the narrator in relation to the story - (examples: first person, third person, limited, omniscient). First Person: “…the main character conveys the incidents he encounters, as well as giving the reader insight into himself as he reveals his thoughts, feelings, and intentions” (Canada). Objective Third Person: “…a ‘nonparticipant’ serves as the narrator and has no insight into the characters' minds. The narrator presents the events using the pronouns he, it, they, and reveals no inner thoughts of the characters” (Canada). Third Person Omniscient: “…‘all knowing’ …narrator [who] Third Person Limited: the narrator focuses on only a few ‘moves from one character to another as necessary’ to provide those characters’ respective motivations and emotions” (Canada). (often only one) characters, sharing thoughts and feelings of that one or those few characters. ◦ Verbal: ◦ Situational: ◦ Dramatic: ◦ Verbal: ◦ Situational: ◦ Dramatic: Sarcasm; you say one thing but mean the opposite. The irony of her reply, “How nice!” when I said I had to work all weekend. An outcome of events contrary to what was, or might have been, expected. (the opposite of what you think is going to happen). The reader/audience knows something that a character does not know. An apparent contradiction that is actually true. ◦Example: “Less is more.” A character that serves by contrast to highlight or emphasize opposing traits in another character. (Both characters may share some similar traits.) http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/lit_terms_f.html Inciting Incident: Rising Action: Climax: Falling Action: Resolution: Denouement: Gustav Freytag was a Nineteenth Century German novelist who saw common patterns in the plots of stories and novels and developed a diagram to analyze them. He diagrammed a story's plot using a pyramid like the one shown here: http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~hartleyg/250/freytag.html Freytag's Pyramid 1. Exposition: setting the scene. The writer introduces the characters and setting, providing description and background. 2. Inciting Incident: something happens to begin the action. A single event usually signals the beginning of the main conflict. The inciting incident is sometimes called 'the complication'. 3. Rising Action: the story builds and gets more exciting. 4. Climax: the moment of greatest tension in a story. This is often the most exciting event. It is the event that the rising action builds up to and that the falling action follows. http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~hartleyg/250/freytag.html 5. Falling Action: events happen as a result of the climax and we know that the story will soon end. 6. Resolution: the character solves the main problem/conflict or someone solves it for him or her. 7. Dénouement: (a French term, pronounced: day-noo-moh) the ending. At this point, any remaining secrets, questions or mysteries which remain after the resolution are solved by the characters or explained by the author. Sometimes the author leaves us to think about the theme or future possibilities for the characters. You can think of the dénouement as the opposite of the exposition: instead of getting ready to tell us the story by introducing the setting and characters, the author ends the story with a final explanation of what actually happened and how the characters think or feel about the events. …It is often very closely tied to the resolution. http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~hartleyg/250/freytag.html Internal: in literature - a struggle which takes place in the character's mind and through which the character reaches a new understanding or dynamic change. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/internal+conflict External: in literature - a struggle between a character and some outside force ◦ Character vs. Character ◦ Character vs. Nature ◦ Character vs. Society http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/external+conflict A kind of writing that ridicules human weakness, vice, or folly in order to bring about social reform. ◦ Examples include most political cartoons and many sections of The Simpsons. The imitation of a person, an author, a work, or type of work typically for comic effect Fallacies are defects that weaken arguments. By learning to look for them in your own and others' writing, you can strengthen your ability to evaluate the arguments you make, read, and hear. Two points to consider about fallacies is that they are common (in ads, newspapers, etc.), and that the level of false-reasoning can range from slight to fully false (an argument can have a very strong section, as well as a weak part to it). Post hoc (also called false cause) This fallacy gets its name from the Latin phrase "post hoc, ergo propter hoc," which translates as "after this, therefore because of this." Definition: Assuming that because B comes after A, A caused B. Of course, sometimes one event really does cause another one that comes later—for example, if I register for a class, and my name later appears on the roll, it's true that the first event caused the one that came later. But sometimes two events that seem related in time aren't really related as cause and event. That is, correlation isn't the same thing as causation. Examples: "President Jones raised taxes, and then the rate of violent crime went up. Jones is responsible for the rise in crime." The increase in taxes might or might not be one factor in the rising crime rates, but the argument hasn't shown us that one caused the other. Tip: To avoid the post hoc fallacy, the arguer would need to give us some explanation of the process by which the tax increase is supposed to have produced higher crime rates. And that's what you should do to avoid committing this fallacy: If you say that A causes B, you should have something more to say about how A caused B than just that A came first and B came later. Ad hominem Definitions: The ad hominem ("against the person") fallacy focuses our attention on people rather than on arguments or evidence. In this argument, the conclusion is usually "You shouldn't believe Soand-So's argument." The reason for not believing So-and-So is that So-and-So is a bad person (ad hominem). In an ad hominem argument, the arguer attacks his or her opponent instead of the opponent's argument. Examples: "Andrea Dworkin has written several books arguing that pornography harms women. But Dworkin is an ugly, bitter person, so you shouldn't listen to her." Dworkin's appearance and character, which the arguer has characterized so ungenerously, have nothing to do with the strength of her argument, so using them as evidence is fallacious. Tip: Be sure to stay focused on your opponents' reasoning, rather than on their personal character. (The exception to this is, of course, if you are making an argument about someone's character—if your conclusion is "President Clinton is an untrustworthy person," premises about his untrustworthy acts are relevant, not fallacious.) False dilemma (or, false dichotomy) Definition: In false dilemma, the arguer sets up the situation so it looks like there are only two choices. The arguer then eliminates one of the choices, so it seems that we are left with only one option: the one the arguer wanted us to pick in the first place. But often there are really many different options, not just two—and if we thought about them all, we might not be so quick to pick the one the arguer recommends. Example: "Caldwell Hall is in bad shape. Either we tear it down and put up a new building, or we continue to risk students' safety. Obviously we shouldn't risk anyone's safety, so we must tear the building down." The argument neglects to mention the possibility that we might repair the building or find some way to protect students from the risks in question—for example, if only a few rooms are in bad shape, perhaps we shouldn't hold classes in those rooms. Tip: Examine your own arguments: If you're saying that we have to choose between just two options, is that really so? Or are there other alternatives you haven't mentioned? If there are other alternatives, don't just ignore them— explain why they, too, should be ruled out. Although there's no formal name for it, assuming that there are only three options, four options, etc. when really there are more is similar to false dilemma, and should also be avoided. Non Sequitur ("It does not follow"). This is the simple fallacy of stating, as a conclusion, something that does not strictly follow from the premises. For example, "Racism is wrong. Therefore, we need affirmative action." Obviously, there is at least one missing step in this argument, because the wrongness of racism does not imply a need for affirmative action without some additional support (such as, "Racism is common," "Affirmative action would reduce racism," "There are no superior alternatives to affirmative action," etc.). Other examples: ◦ I deserve an A in chemistry because I studied really hard. ◦ This car is the best because it is made in Italy. This fallacy occurs when the evidence presented doesn't logically support its claim. Studying hard won't necessarily earn you good grades on assignments (or an A). Both poorly made cars and fabulous cars are manufactured in Italy, so we can't assume a car is "the best" because it was made there. Non sequiturs cause arguments to essentially collapse. Final Example: ◦ Non Sequitur: The current healthcare program will be ineffective because almost all Republican congressmen opposed the legislation for it. ◦ More logical argument: The current healthcare program will be ineffective because it does not safeguard against skyrocketing health insurance premiums. Propaganda is a specific type of message presentation, aimed at serving an agenda. Even if the message conveys true information, it may be partisan and fail to paint a complete picture. The primary use of the term is in political contexts and generally refers to efforts sponsored by governments. A similar manipulation of information is well known, such as in advertising, but normally it is not called propaganda in this context. The word propaganda carries a strong negative connotation that advertising does not. http://www.history.ucsb.edu/projects/ccws/conflicts/P DF/terrorism/kelly.pdf Propaganda can serve to rally people behind a cause, but often at the cost of exaggerating, misrepresenting, or lying about the issues in order to gain that support. While the issue of propaganda often is discussed in the context of militarism, war and warmongering, it is around us in all aspects of life. Common tactics include: using selective stories that may appear to be objective; partial facts; using only a part of a conversation; using narrow resources of “experts” to provide insights for a situation (for example: interviewing retired military to comment upon a current conflict, or treating government sources as fact, rather than as one perspective that needs to be verified or researched); demonizing the enemy; http://www.history.ucsb.edu/projects/ccws/conflicts/PDF/te rrorism/kelly.pdf