Essentialism and Progressivism: The Battle for Priority in Public

advertisement

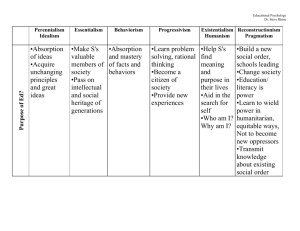

Essentialism and Progressivism: The Battle for Priority in Public Schools Lisa Brown 12-9-11 Sonoma State EDCT 585 Lisa Brown 12-9-11 EDCT 585 Abstract: Essentialism and Progressivism: The Battle for Priority in Public Schools Overview/Summary of Project After being introduced to the major philosophies in our first reading from Ornstein, I was interested in looking further into progressivism and essentialism. It seemed to me that these two theories, while quite different, both had a hold on public education practices today. I wanted to look more into the background of these theories and how I see them used today by fellow teachers and in my own practice. My initial thought was that I agreed the most with progressivism but the more I thought about my practice, the more essentialism theory I noticed. I wanted to see if my practice needed to change or my thoughts towards essentialism. What I Have Learned from this Project Simply put, I learned that essentialism and progressivism are two theories that both want what they think is best for the child. Both want students to learn vital information and be successful. The differences lie in what the vital information is and how the information should be relayed to the student. Implications in my Professional Life As long as I teach in a public school, the current bureaucratic education system is going to want a universal formula for success and essentialism is easiest way to measure that. Learning how to take the progressive ideals and work them into the structure that we have today is a vital skill for teachers to have. The same goes for thinking and challenging the how and why of our practice. As long as I reflect on what I am doing and how I could do it better, labels don’t matter. I learned that essentialism and progressivism have their extreme theorists who take things a little to far but they have the same goal to educate students. Progressivism Progressivism is wide portion of curriculum theory. It got its start in the 19th century out of the pragmatic theory and as an alternative to perennialism. This area of curriculum theory, as its name suggests, stems from the enthusiasm to offer a different kind of education from whatever the norm is. The teaching method emphasizes problem solving and scientific inquiry. Material is to be to taught with more hands-on activities with group work and collaboration. The emphasis was not on what to think but how to think (Ornstein 1988). Democracy Democracy plays a key role in progressivism, especially in the work of John Dewey. Students need to learn how to think critically to be able to participate in a democracy. Democracy doesn’t mean blind patriotism but the belief, “that authentic democracy emerges when people are given opportunities to participate as relative equals on common efforts to improve their society” (Schultz, 2011, p. 492). Montessori One example of a progressivist educator is Maria Montessori. She looked at progressive education as a more holistic approach and focused more on the developmental needs of children. Classrooms that follow her methods stress student creativity and the idea that students can ‘learn by doing,’ not by being talked at (Hayes, 2008). Unlike the often very scientific approach of essentialist theorist, who proved their point with data driven research, Montessori’s work was mostly based off of her own work with and observing children. Montessori schools, especially pre-K to first grade, are one of the most recognized alternative choices parents have to traditional public schooling with over 3,000 schools in 1997 (Martin, 2004). The teacher-student relationship in progressivism steps away from the traditional lecture format. Student-centered activities play a large role in instruction and the teacher is more a guide to find students’ passions and interests. A common belief was that, “Learners must be motivated and interested in the learning task, and the classroom should be based on real life experiences” (Ornstein, 1988, p. 38). Paulo Freire is one such theorist and clearly defined his idea of what the teacher-student role should be. Instead of the essentialist ‘banking’ method he believed that teachers should enter a dialectic twoway communication relationship where both the student and teacher learn from each other. Student interest and background knowledge were essential to what was to be taught (Freire, 1970). Progressivism is a huge area of educational philosophy and can be interpreted in many ways. Within this philosophy there are other theories that take the progressivist model a few steps father. Reconstructionism, conflict theory and critical theory are some examples. Essentialism Progressivism was making headway by the 1930’s and John Dewey’s work was becoming widely respected, but not by all. The term essentialism was coined during this time period and was seen as an alternative to progressivism. Some educators were frustrated with progressivism’s approach and wanted a philosophy more connected to idealism and realism of Plato and Aristotle. Essentialism is a theory based on teaching the basic fundamentals that students need to learn. Unlike Perennialism, which felt these facts and ideas are timeless, and Progressivism, which was highly feed by student’s interest, essentialist curriculum focused on what students needed to know now. These, ‘back to basics’ topics are what our school systems still focus on today; English, Math, Science, history and a foreign language (Ornstein, 1998). Essentialism continued to take hold in American schools, especially in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The Cold War and Sputnik had Americans afraid that we were losing control and power as the top country. People wanted a philosophy and set of curriculum that would improve our science and math and bring us back on top. Essentialism’s explicit, structured method was seen as a good fit for it. This time also brought fears of communism or any government/ideology different from our own. Dewey is often cited for his ideas in progressive democracy but many essentialists considered preparing for a democracy to be an important part of education as well. However, this form of democracy was more about the moral and patriotic form of democracy and less about freedom of choice and thought (Null, 2007). According to this theory, the teacher is the knowledge source and their job is to explicitly teach the specified topics. This authoritarian teacher, often negatively called “sage on the stage” used the Freirian banking concept mention earlier. Essentialism would argue that the teacher is the one with the education and training and it makes perfect sense that they should have complete control as the expert. Student input was not a priority because they are not mature enough to know what it best (Yilmaz, 2011). At the same time Bagley stressed that while teachers need to be knowable in their subject area they also have to be trained in how to be a good teacher too. He worked with some with teaching training programs during his career to help full this need (Null, 2007). Hidden Premises and gap in the theories Progressivists and other critics find fault in the essentialist approach and, “believe inflexible state curricular standards enforced by high-stakes tests are restricting teachers’ flexibility in employing methods other than teacher-centered direct instruction” (Hayes, 2008, p. 153). Not all subjects can be tested and not all knowledge can be prepackaged into clearly defined subject matter. Essentialist might even have the best concepts for students to learn, but if they don’t move away from the authoritarian teacher model and work more on student engagement and active learning the students won’t want to learn or remember what they learned. The subject matter can’t be made the same for all children either. Different students will have different wants and needs in education. Progressivism needs student buy in and engagement to work. If students don’t want to engage in the student-centered activities and be willing to think past the basic concepts they will struggle. This can especially be a problem if the students are used to a more essentialist approach in the classroom (Schultz, 2008). Students need to specifically learn how to function in this type of classroom. Another critique of progressivism is the struggle to test. Progressivism does use assessments, more often project based and short answer but it is harder to quantify and ‘prove’ to the nation that our students are succeeding. As a country we want some control on what and how curriculum is taught to children (Bagley, 1940). This theory doesn’t allow as much government input as essentialism. Comparison of the Theories At first glance these two theories seem to be polar opposites and theorists from both camps have often crashed over their ideals. Essentialists see the classroom as teacher-centered, while progressivists take a more student-centered approach. Both expect the teacher to be well educated and knowledgeable with the subject matter, but the way they impart that knowledge can be at opposite ends of the spectrum. Essentialism has a more strict expectation of what will be learned in the classroom and at what age, while on the other hand, progressivists look more towards ‘teachable moments’ and take student interest into account. Educators today, myself included, seem to be grappling with ways to combine these two theories to get the best of both worlds. There can be a time and place for implementation of both. John Dewey said it best, “What we want and need is education pure and simple, and we shall make sure and faster progress when we devote ourselves to finding out just what education is and what conditions have to be satisfied in order that education may be reality and not a name or slogan” (Hayes, 2008, p. 120). Criteria to judge the quality of the curriculum When jugging or critiquing these theories, one must think about what the aim of education is. Both philosophies want to create well-educated, successful students and they both do. After talking this class I am not sure if I am more or less confidant in what I would use to judge a theory. The simple answer is to create a scientific essentialism rubric. Standardized assessment alone would show that essentialism does work well if we want students to memorize fact (Loewen 2010). Assessment and standards has been an issue that both sides have argued over. Progressives and other educators often simplify essentialism as a theory that only cares about testing and standards. “They claim that these policies discriminate against minority students, undermine teachers, reduce opportunities for students to engage in creative and complex learning assignments, and deny high school diplomas because of student’s failure to pass subjects they were never taught” (Hayes, 2008). However, this is an over simplification of the essentialist theory. The core ideals are not about testing, even though that aspect of essentialism is what we see the most today. Students need to learn the basics. Standards and assessment are just the easiest way to demand and prove that these skills are being taught and mastered. Having a mixture of both of these theories in my own beliefs and practice, I looked for the following elements when critiquing. 1. Student interest and engagement: Progressivism would win this round. The students don’t have to be the ones that get to decide the curriculum but the teacher needs to find a way to make the material meaningful. 2. Preparation for adulthood and workforce: Both hit this target but in different ways. Essentialism will give you the tools needed to get into college and create a solid foundation for further inquiry. It also teaches the ‘moral readiness’ needed for adult life. Progressivism would help students find their passion and interest when it would come to a job and hopefully create life long learners. What is its relevancy to contemporary society? Both theories are still very relevant today. Bagley’s and Dewey’s work in the 1930’s details and bemoans the same issues educators are dealing with day. Some progressivist see little change bringing brought forth in public education and have turned to charter schools as a way to bypass some of the essentialist red tape. Charter schools often used the names of progressive theorist like Montessori and Freire to remind them of what they are working towards. Essentialism is arguably the most widely used educational philosophy in America today. We have adopted No Child Left Behind to evaluate and critique both student and teacher. State standards and benchmark testing are the norm in school districts. Today the new emphasis is on the Common Core standards that will supposedly help students “succeed in entry-level, credit-bearing academic college courses and in workforce training programs” (http://www.corestandards.org, 2011). Teachers might have some leeway in how they teach, but only so long as they follow the standards and their students preform well on tests. This testing priority is only a type of essentialism however. A more current curriculum theorist who is influencing teachers and parents in the benefits of the essentialism philosophy is E.D. Hirsh. Hirsh (2011) is well known for his ‘What every child should know in_____’ books and his curriculum called Core Knowledge and believes, “By outlining the precise content that every child should learn in language arts and literature, history and geography, mathematics, science, music, and the visual arts, the Core Knowledge curriculum represents a first-of-its kind effort to identify the foundational knowledge every child needs to reach these goals–and to teach it, grade-by-grade, year-by-year, in a coherent, age-appropriate sequence” (Hirsh, 2011 p.1). His work focuses on the need for a specific set of skills and knowledge for students to learn depending upon their grade level. Teacher and student choice is not the main concern and he believed, “The cause of bad K–12 is the lack of specificity and coherence in the K–12 curriculum” (Hirsch, 2011, p.1). Which Theory do I support and What Have I Learned? I struggle with this question now, if not more so then I did in the beginning of the semester when I first read Ornstein’s paper. My ideals are very much centered around progressivism. I try to guide my students through their thinking and develop student centered inquiry based projects. I get excited to hear about how teachers are able to reach their students and get around the ridged box of standards and benchmark tests. Despite all my passion and enthusiasm towards the ideals of progressivism, I see so much more of essentialism in my teaching practice. I can impart lay blame on the school system and what my principal and school board expect of me. I give the required quarterly benchmark assessments to my students and at times, “teach to the test” to make sure my students ‘prove themselves’ to the school board. As long as I keep my scores up I am allowed leniency in what or how I teach. . . but that would change if my scores go down. I naively or not, think that the standards are there for a reason, there must be good reasons that students need to learn this and if I don’t get around to it, who will? I think this mixture and confusion I have on how to teach is actually a good thing. As long as I teach in a public school, the current bureaucracy is going what a universal proven formula for success and essentialism provides that. Learning how to take the progressive ideals and work them into the structure that we have today is one of the most vital skills for teachers to have. The same goes for thinking and challenging the how and why of my practice. As long as I reflect on what I am doing and how I could do it better, labels don’t matter. I learned that essentialism and progressivism have their extreme theorists who take things a little to far but they have the same goal to educate students; its just how and what that means exactly that is up for interpretation. EXTRA BULLET: What Examples of these Theories do I Notice in My School/Co workers Practice as I Write this Paper As soon as I decided to choose this topic for my paper I knew I wanted to add this to my paper. I didn’t just want to reflect on the practices that I have seen at the end, but to take quick notes (I love the EverNote app for IPhone and computers!) when I see and hear them at school; especially during staff meetings and lunchroom discussions. This process brought me the title Essentialism and Progressivism: The Battle for Priority in Public Schools. I saw the battle teachers were making against the essentialist practices forced on us from the school board and district. I saw how some teachers had given up and were towing the line and other teachers; especially the seasoned teachers ironically, were ready to fight for their way of teaching. We would be given a formula for what was expected in instruction/assessment, like writing, and later on in the teachers room we would discuss what we were really going to do instead! (Writing is subjective!) The 5th grade teacher has been frustrated with the fluency/reading rate benchmark that is given to the school board to review. How can she help students read quicker at this age, other then repetition? Isn’t there a better test to show how the students are progressing in her class? The principal gave no satisfactory answer yet. We are lucky enough that most rules are told, but not enforced---as long as our benchmarks scores are high enough. Some progressive ideals are encouraged at my school. The principal and teachers with their classes, came to see my students Egypt Musical and I go to 2nd grades when they do theirs. We have a garden, which they tried to structure and assign grade level standards to, but in the end, its parent volunteers spraying the kids with the hose and kids picking weeds. We don’t have a pacing guide for any material and while we keep close tabs on language arts and math, science and social studies have been given more free reign for teacher choice. Again, I think doesn’t come down to an either or but a mix of the two. As long as we are battling for what we think is right, our students will receive a good education. References Bagley, W.C. (1940) “Just What is the Crux of the Conflict Between the Progressive and the Essentialist,” Educational Administration and Supervision Vol XXIV pp. 508-511 Hayes, W. (2008). The Future of Progressive Education, Educational Horizons, Spring 153-160 Ornstein, A.C., Hunkins, F.P. (1988) “Philosophical Foundation of Curriculum, Curriculum: Foundations Principles and Issues, Prentice Hall, New Jersey pp. 25-51 Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY, Continuum Intl Pub Group. Martin, R. (2004). Philosophically Based Alternatives in Education. Encounter, 17(1), 17-27. Loewen, J. W. (2010). Teaching what really happened, how to avoid the tyranny of textbooks and get students excited about doing history. Teachers College Pr. Null, J. (2007). William C. Bagley and the Founding of Essentialism: An Untold Story in American Educational History. Teachers College Record, 109(4), 1013-1055. Schutz, A. (2011). Power and Trust in the Public Realm: John Dewey, Saul Alinksy, and the Limits of Progressive Democratic Education. Educational Theory, 61(4), 491512. YILMAZ, K., ALTINKURT, Y., & ÇOKLUK, Ö. (2011). Developing the Educational Belief Scale: The Validity and Reliability Study. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 11(1), 343-350. Common Core State Standards Initiative. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ Hirsh, E.D. Core Knowledge. (2011). Retrieved from www.coreknowledge.org