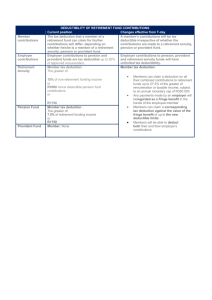

1.4 MB - Financial System Inquiry

advertisement