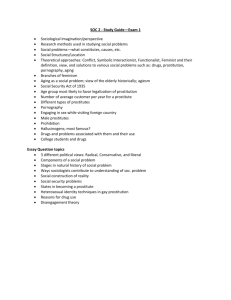

south korea prostitutes

advertisement