Strategic Plan 2015 2020. - naturalresources.sa.gov.au

advertisement

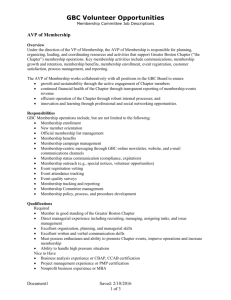

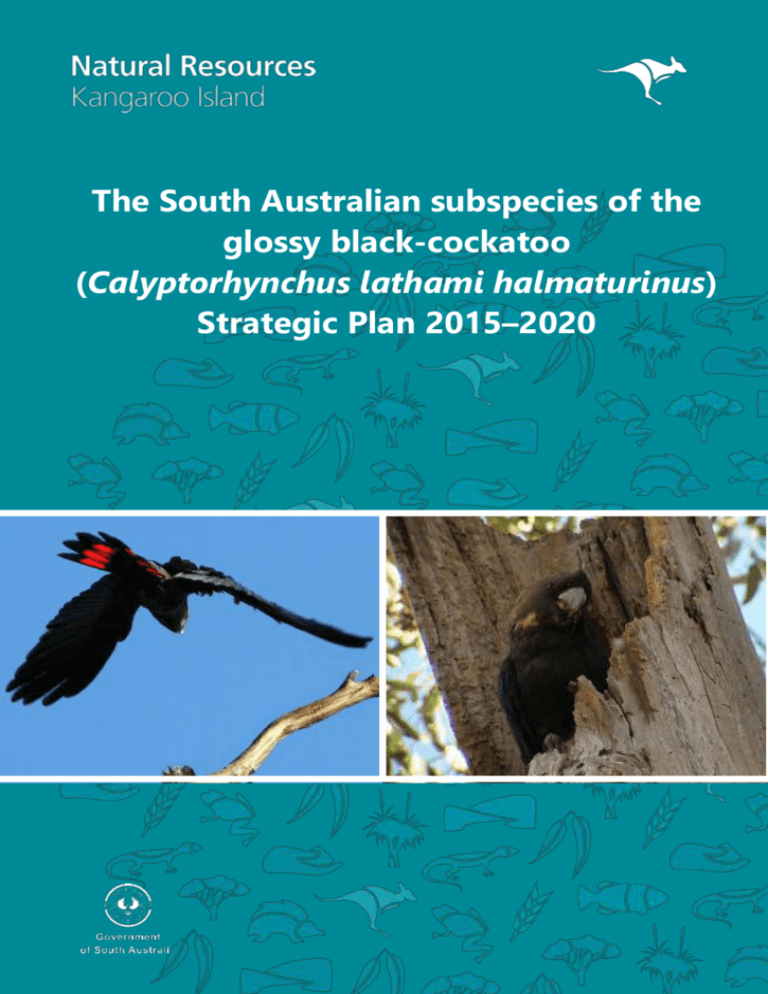

The South Australian subspecies of the glossy black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) Strategic Plan 2015–2020 The South Australian subspecies of the glossy black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) Strategic Plan 2015–2020 ISLAND REFUGE BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PROGRAM A report by Natural Resources Kangaroo Island for the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board by Dai Morgan, Mike Barth and Martine Kinloch 2015 This project is supported by the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board, through funding from the Australian Government. The South Australian subspecies of the glossy black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) Strategic Plan 2015–2020 The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this report are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. The Natural Resources Kangaroo Island shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. Project Officer Contact Details Glossy Black-cockatoo Project Officer Natural Resources Kangaroo Island 37 Dauncey St Kingscote SA 5223 Phone: (08) 8553 4444 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The South Australian subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) is listed as Endangered under the Australian Government Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). Once more widespread, it is now found only on Kangaroo Island. The long-term aims of the Recovery Program for the Glossy Black-cockatoo (GBC), as defined in this Strategic Plan and the preceding Recovery Plan (2005-2010) (Mooney and Pedler 2005) are: 1. To ensure that a viable breeding population of the Glossy black-cockatoo persists in South Australia. 2. To shift the status of the South Australia Glossy black-cockatoo from Endangered (<125 adult females and <125 adult males) to Vulnerable (125 – 500 adult females and 125 – 500 adult males) by 2030. 3. To expand the current distribution of the SA Glossy black-cockatoo to include its former range on Fleurieu Peninsula. In order to realise these long-term aims, five short-term objectives have been established: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Maintain or improve GBC nesting success rates on Kangaroo Island Protect, enhance and increase GBC habitat Improve knowledge of GBC ecology in order to refine management strategies Improve community awareness and stewardship of the GBC Recovery Program Implement a monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) framework for the GBC Recovery Program The rationale for each objective is explained and Targets that may be used to measure progress towards the objectives are also defined. Finally, each objective is assigned a priority rating from low to very high, to provide guidance for managers needing to allocate investment in the GBC Recovery Program. Acknowledgments The authors thank members of the Glossy Black-cockatoo Recovery Team for comments that improved this document. Thanks also to Karleah Berris for finalising the editing process. The development of this Strategic Plan was funded through a Caring for Our Country grant. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .........................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Purpose and scope .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 GBC Recovery Team ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Community engagement ................................................................................................................ 6 2. Threats to Glossy Black-cockatoos ..............................................................................................6 2.1 Habitat loss through land clearance and fire .................................................................................. 6 2.2 Nest predation ................................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Competition for nest hollows ......................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Disease ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. GBC Recovery Program Objectives 2015-2020 .............................................................................8 Objective 1: Maintain or improve GBC breeding success rates on Kangaroo Island ............................ 8 Objective 2: Protect, enhance and increase GBC habitat ..................................................................... 9 Objective 3: Improve knowledge of GBC ecology in order to refine management strategies ........... 10 Objective 4: Increase community awareness and stewardship of the GBC Recovery Program......... 11 Objective 5: Implement a monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) framework for the GBC Recovery Program ........................................................................................................... 12 4. References ............................................................................................................................... 13 Box 1. Guidelines for assessing the conservation status of the South Australian subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. The proportion of monitored GBC nests that successfully fledged a nestling (1998 – 2014). Prior to implementation of the Recovery Program, breeding success was estimated at 23%..............................4 Figure 2. The number of GBCs recorded in each annual census (1995 – 2014). Straight line represents a linear regression showing the population trend over time………………………………………………………………………4 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Background The South Australian subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus; GBC) is found only on Kangaroo Island, South Australia. It is recognised nationally as Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) as a result of its small population size and limited geographical distribution. The other two subspecies of GBC, C. l. lathami and C. l. erebus, which are found on the east coast of the Australian mainland, have a conservation status of Near Threatened and Least Concern, respectively (Garnett and Crowley 2000). A GBC Recovery Program (RP) began in the mid-1990s when the estimated GBC population size was 188 individuals; although a survey conducted in 1993 recorded only 136 birds (Pepper 1997). At that time, recruitment into the population was low, mainly because of poor breeding success (c. 23%) resulting from egg and nestling predation by brush-tailed Possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) (Garnett et al. 1999). Management was initiated to protect nest trees from Possums and other threats, and since then breeding success rates have generally been over 45% (Figure 1). Artificial nest boxes have also been installed in suitable breeding habitat where a shortage of natural tree hollows exists (Garnett et al. 1999; Mooney and Pedler 2005) to increase reproductive output. Currently, nesting has been observed at 174 known natural tree hollows and an additional 100 artificial nest boxes have been installed; these nests are monitored each breeding season (e.g. Barth and Morgan 2013). As a result of management initiatives, the number of GBCs counted during the annual census has increased from consistently less than 200 prior to 1997, to 356 individuals in 2014 (Figure 2). In addition to promoting breeding success, research on the behavioural ecology of the GBC has been carried out to increase knowledge of breeding biology, demography, survival rates and movements of birds. This has been achieved by nest monitoring, banding studies, and conducting an annual census (Garnett et al. 1999; Mooney and Pedler 2005; Morgan and Barth 2013). Restoration of GBC habitat, particularly plantings of drooping sheoak, has also increased the extent of GBC foraging and nesting habitat (Crowley et al. 1998; GBC RP unpublished data). 3 80 70 % Successful Nests 60 50 40 30 20 10 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 0 Figure 1. The proportion of monitored GBC nests that successfully fledged a nestling (1998 – 2014). Prior to implementation of the Recovery Program, breeding success was estimated at 23%. 400 300 250 200 150 100 50 2014 2013 2012 2011 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 0 2010 y = 6.7977x + 190.77 R² = 0.6588 2009 Number of Individuals 350 Figure 2. The number of GBCs recorded in each annual census (1995 – 2014). Straight line represents a linear regression showing the population trend over time. 4 1.2 Purpose and scope This Strategic Plan arose from a review of the objectives and recommendations described in the Recovery Plan for the South Australian Subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) 2005 – 2010 (Mooney and Pedler 2005). Much of the associated background information in the 2005 – 2010 Recovery Plan is still relevant, particularly as it relates to aspects of GBC ecology and recovery planning and is not reproduced here. It is recommended that the 2005 – 2010 Recovery Plan be consulted in conjunction with this Strategic Plan to gain a complete appreciation of South Australian Glossy Black-cockatoo biology and ecology, and the history of the Recovery Program. The three original long-term objectives, as outlined in the 2005-2010 Recovery Plan are: 1) to ensure a viable breeding population persists; 2) to shift the status of the GBC from Endangered to Vulnerable by 2030; and 3) to expand the current distribution of the GBC to include its former range on the Fleurieu Peninsula (Mooney and Pedler 2005). These goals can be achieved by consistently maintaining nesting success rates at >45%, increasing the minimum number of birds counted during the annual census to at least 350 (see Box 1) and increasing the amount of glossy black-cockatoo habitat. Using the regression equation provided in Figure 2 (y= 6.7977x +190.77) and assuming the population continues to increase at the current rate, the population target of 350 birds should be reached by 2019. The purpose of this document is to present a strategic plan for achieving the goals of the recovery program over the period 2015 – 2020. Five short-term objectives have been identified to address the goals of the recovery program: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Maintain or improve GBC nesting success rates on Kangaroo Island Protect, enhance and increase GBC habitat Improve knowledge of GBC ecology in order to refine management strategies Improve community awareness and stewardship of the GBC Recovery Program Implement a monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) framework for the GBC Recovery Program The Plan defines these five short-term objectives for the GBC RP as well as targets that can be used to quantify progress towards the successful completion of each objective. Strategies and actions that may be employed to realise the targets are also described. The relative importance of each objective has been ranked (from low to very high) in order to provide guidance to managers needing to prioritise investment in the GBC RP should funding be limited. Finally, the relative significance of each Action has also been ranked (as above) in order to indicate its contribution to realising a given objective. While the objectives and targets are relatively fixed over the Strategic Plan period, the strategies and actions should be applied with a degree of flexibility as they reflect the approach of the RP to realising the objectives at the time of writing this document. It may be appropriate for existing strategies and actions to be modified, or new ones to be created, in the future. 5 1.3 GBC Recovery Team A GBC Recovery Team was established “to coordinate GBC conservation activities and to guide the implementation of the Recovery Plan to ensure actions are effective and technically sound” (see Recovery Team Terms of Reference for the South Australian Glossy Black-cockatoo Calyptorhyncus lathami halmaturinus). The Recovery Team generally meets twice a year and membership consists of expert ecologists and ornithologists, landowners, volunteers, and representatives of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resource Management Board, the Department of Environment, and Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Kangaroo Island management staff. Such a broad assemblage of members ensures that a wide variety of expertise and interests are represented. 1.4 Community engagement The GBC RP has been well supported since its inception by volunteers taking part in on-ground activities such as nest monitoring, tree planting and the annual census. Furthermore, more than 60% of GBC nesting and feeding habitat is located on privately owned land, so the Program is also heavily reliant on the support of these stakeholders in order to gain access to sites. Accordingly, community engagement to maintain support and awareness of the Program has always been a high priority and considerable effort has been invested in fostering and maintaining these relationships. For example, RP staff support a recently established (2012) GBC volunteer group (Friends of the Glossies) and regularly give community presentations and produce media outputs. 2. Threats to Glossy Black-cockatoos 2.1 Habitat loss through land clearance and fire GBCs were historically distributed across the Mount Lofty Ranges south of Adelaide (Joseph 1989). Habitat loss, primarily through land clearance for agricultural development, harvesting trees for timber/firewood and wildfires, is believed to have contributed to GBC’s becoming extinct on the mainland (Joseph 1989). The last confirmed sighting was in 1977 (Cleland and Sims 1968; Joseph 1989) and the GBC is now restricted to Kangaroo Island. The GBC’s very specific resource requirements are likely to have exacerbated the effect of habitat loss ; they predominantly nest in hollows found in oldage sugar gum trees (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) and feed on the seeds of drooping sheoak (Allocasuarina verticillata) (Cleland and Sims 1968; Joseph 1982; Garnett et al. 1999; Chapman 2005). Habitat loss through fire is currently considered a significant threat to GBC habitat (e.g., Pepper 1992). In contrast, land clearance of suitable GBC habitat on Kangaroo Island is not regarded as a major issue because much of the feeding and nesting habitat exists outside of agricultural areas or within the conservation estate. However, these areas only make up only 1-2% of land cover on Kangaroo Island (GBC RP data); therefore, any disturbance is of concern. 6 2.2 Nest predation Predation of eggs and nestlings by overabundant brush-tailed possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) is considered the most significant current threat to GBC nesting success (Garnett et al. 1999). Installing and maintaining corrugated iron collars around the base of nest trees and regularly pruning overhead limbs to prevent access to nest hollows from adjoining canopies has increased nesting success rates from c. 23% to >45% most breeding seasons since the start of the GBC RP (Garnett et al. 1999; Mooney and Pedler 2005; GBC RP Breeding Season Reports; Figure 1). Other species such as galahs (Eolophus roseicapilla), sulphur-crested Cockatoos (Cacatua galerita), and little corellas (Cacatua sanguinea) have all been implicated as causes of nest failure (Mooney and Pedler 2005); however, the relative importance of these species is not fully understood. 2.3 Competition for nest hollows Interspecific competition for nest hollows may limit GBC breeding success rates. Yellow-tailed blackcockatoos (Calyptorhynchus funereus; YTBC), feral honey bees (Apis spp.), wood ducks (Chenonetta jubata), brush-tailed possums, galahs and little corellas all exploit hollows that could be nested in by GBCs. The YTBC breeding season is between October-March (Simpson and Day 2010) and there is significant overlap with GBCs (January-October); however, there is no active management to remove YTBC from potential GBC nesting sites as they are of conservation concern in other areas. The threat from possums is reduced through the installation of iron collars around the base of nest trees or pruning over hanging branches (see above), while feral bee hives in hollows are removed, and galahs and little corellas deemed to be a threat in GBC nesting areas are controlled. Wood ducks are not controlled; however, old eggs are removed from GBC hollows during the nest maintenance period each year. 2.4 Disease The risk of avian disease in the GBC population has received little attention in the past; however, viruses such as circovirus or psittacine herpes could have significant impacts on GBC if they become established on Kangaroo Island. This is primarily because the GBC population is small and movement of birds between flocks is common, which would exacerbate infection rates. Currently, there are no known diseases limiting the GBC population; however, it is possible that diseases may arrive on the island from the mainland via other cockatoo species. 7 3. GBC Recovery Program Objectives 2015-2020 Objective 1: Maintain or improve GBC breeding success rates on Kangaroo Island Rationale: Investing considerable resources into promoting breeding success is the most practical way of guaranteeing sufficient recruitment to increase the size of the GBC population. When nesting success rates improved to >45%, a steady increase in the population size has generally been observed (Garnett et al. 1999; Mooney and Pedler 2005; Figure 1). Current investment priority of Objective 1: VERY HIGH. Target Strategy Action 1. Annual breeding success rates are maintained at >45% A. Protect nests from Possum predation. A1. Install (and maintain) corrugated iron collars around the bases of nest trees. A2. Prune overhanging branches to prevent possum access from adjacent trees. Priority for realisation of Objective Very high Very high B. Ensure that artificial nest hollows are in usable condition prior to the GBC breeding season. B1. Maintain 50% of artificial hollows each year (e.g. remove old eggs or Very high other species [such as bees], and repair hollows). C. Reduce the impact of feral Bees on GBC nesting success. C1. Manage bees at all natural and artificial hollows that can be accessed (e.g. poison and remove hives, insert bee deterrents into hollows and investigate and test new methods for controlling feral bee populations). High D. Reduce impacts from other species on GBC nesting success. D1. Control other nest competitors (e.g. little corellas) so that ≤5% of GBC nests are affected by other species. Moderate 8 Objective 2: Protect, enhance and increase GBC habitat Rationale: If breeding success is maintained at its current rate, recruitment into the population will increase, potentially exerting pressure on current resources. Unless they are increased or enhanced, and adequately protected, population growth will be limited. Furthermore, Kangaroo Island is expected to warm by up to 1.5 oC and receive up to 20% less rainfall by 2050 due to climate change effects (Harris et al. 2012). Under some scenarios, these effects are predicted to reduce GBC habitat (Harris et al. 2012). Identifying and managing appropriate areas on Kangaroo Island that will support GBC food trees under future climate scenarios is therefore important in securing foraging habitat in the medium- to long-term future. Protection and re-establishment of potential habitat in the Fleurieu Peninsula should be encouraged by the program. Current investment priority of Objective 2: HIGH. Priority for realisation of Objective Target Strategy Action 1. By 2020, 50 ha of GBC habitat has been protected or enhanced. A. Identify priority sites in the landscape for revegetation and/or protection. A1. Conduct spatial analyses using Kangaroo Island vegetation cover and GBC distribution datasets. High 2. By 2020, 50 ha of GBC habitat has been reestablished. B. Secure funding and landholder support for onground works and stewardship arrangements. B1. Fence GBC habitat to exclude access from browsing animals. B2. Plant and protect trees to create or enhance GBC habitat. B3. Engage and assist landowners with covenant agreements that will legally protect high value GBC areas. B4. Secure biodiversity offsets for any proposal that will result in the loss of significant GBC habitat. B5. Liaise with stakeholders in the Fleurieu Peninsula to conserve GBC habitat and encourage habitat re-establishment. C1. Engage with regional fire management officers, CFS, and Kangaroo Island Council. C2. Conduct site visits in areas that may be used for breeding to identify potential nesting trees. High 3. Less than 15% of feeding habitat burnt between 2000-10 is under a fire management regime at any moment in time. 4. Protect all known and potential nesting trees from burning. C. Ensure that GBC habitat protection measures are included in fire management plans. Very high Moderate High High Very high High 9 Objective 3: Improve knowledge of GBC ecology in order to refine management strategies Rationale: There is considerable ecological information about the breeding biology, foraging behaviour, and long-term viability of the GBC population on Kangaroo Island (e.g., Pepper 1996; Garnett et al. 1999; Chapman 2005; Harris et al. 2012). However, further research will improve this knowledge and also address other management questions that have not received enough attention in the past. Current investment priority of Object 3: HIGH. Target Strategy Action 1. Production of at least one output per annum that increases knowledge of GBC ecology or threatening processes. A. Identify and address key knowledge gaps. A1. Obtain accurate data on the breeding productivity of the GBC population by monitoring at least 50 active nests at representative locations across Kangaroo Island each breeding season. A2. Obtain accurate time series data to track trends in GBC population size and distribution by conducting an annual census of all known post-breeding flocks. A3. Collect demographic data on the GBC population such as survival rates, age structure and sex ratio and other life history parameters by identifying individuals to gender and age class during the census and reading band numbers on marked birds. A4. Monitor vegetation response to management actions by assessing areas that have been improved or enhanced using an appropriate vegetation assessment tools at two and five years after management was initiated. A5. Conduct field surveys and trials to obtain information on potential risks to GBC survival; for example, determining the threat of avian disease transfer from other cockatoo species to GBCs. B1. Keep abreast of research on, and management of, other cockatoos and endangered species. B. Investigate emerging threats to GBCs. Priority for realisation of Objective Very high Very high Very high Moderate High High 10 Objective 4: Increase community awareness and stewardship of the GBC Recovery Program Rationale: The GBC RP relies heavily on the support of many stakeholders and more than 60% of GBC habitat is located on private lands. Therefore, maintaining community awareness of the Program, understanding what motivates stakeholder participation, quantifying levels of satisfaction with the RP, and modifying activities accordingly, will promote engagement and foster community support for the GBC RP. Current investment priority of Object 4: HIGH. Priority for realisation of Objective Target Strategy Action 1. At least 20 volunteers, contributing a minimum of 400 hours to the GBC Program per annum. A. Maintain the GBC RP’s high profile at local, state, national and international levels. A1. Publicise the GBC Program through the production of local, state or national publications and presentations. A2. Maintain a website describing the GBC Program and its achievements. Moderate 2. No decrease in numbers or regional spread of stakeholders allowing access to private properties in order to implement the GBC RP. B. Actively recruit and retain volunteers and landholders within the GBC Program. B1. Maintain a database documenting volunteer contributions to the RP. B2. Advertise events and ask for volunteer participation through multimedia outlets. B3. Regularly disseminate results to volunteers and landholders through newsletters and personal contact. B4. Seek and respond to feedback in a timely fashion to improve volunteer satisfaction levels. B5. Support a volunteer group (Friends of the Glossies) dedicated to assisting the GBC RP. B6. Provide training to increase volunteer capacity to deliver on-ground actions. B7. Adhere to all conditions of entry stipulated by the landowner. B8. Advertise the availability of funding to landholders to support on-ground habitat restoration work. Very high Moderate High High Very high High High Very high High 11 Objective 5: Implement a monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) framework for the GBC Recovery Program Rationale: A MERI framework will permit assessment and review of progress towards achieving the Long-term Objective of the Strategic Plan. It will also allow results, lessons, and new knowledge to be incorporated into the planning and delivery of Objectives 1 – 4. Current investment priority of Object 6: HIGH. Target Strategy Action Priority for realisation of Objective 1. Production of an annual report (including a ‘Report Card’) that provides quantitative measures of performance against each Target from Objectives 1 – 4. A. Invest sufficient resources into achieving the Targets described in Objectives 1 – 4. A1. Report on the progress made against Objectives 1 – 4. High B. Evaluate RP performance annually to identify where improvements could be achieved to increase efficacy or quality of data collected. B1. Report potential improvements in the annual report and implement if possible. High C. Quantify volunteer and stakeholder satisfaction levels with the GBC RP. C1. Conduct a volunteer and stakeholder survey at the midway and end points of the Strategic Plan. C2. Integrate results from surveys into volunteer and stakeholder management to increase satisfaction levels. High D. Ensure that reporting focuses on addressing the Strategic Plan Objectives. D1. Structure the annual report and the agenda of Recovery Team meetings to address each Objective. Moderate E. Secure funding towards the end of the Strategic Plan period to complete a revised Recovery- or Strategic Plan. E1. Prepare funding proposals to secure funding to develop a new Recovery- or Strategic Plan. High 2. A mid-term review that summarises and evaluates progress towards Objectives 1 – 4. 3. A revised Recovery Plan or Strategic Plan in 2021. High 12 4. References Barth, M.; Morgan, D. 2013. Annual breeding season report 2012.Recovery Program for the South Australian Subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus). Unpublished Report: Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources. Chapman, T.F. 2005. Cone production by the drooping sheoak Allocasuarina verticillata and the feeding ecology of the glossy black-cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus on Kangaroo Island. Unpublished PhD Thesis. School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Discipline of Environmental Biology. University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia. Cleland, J.B.; Sims, E.B. 1968.Food of the Glossy Black Cockatoo. South Australian Ornithologist 25: 4752. Crowley, G.; Garnett, S.; Meakins, W.; Heinrich, A. 1998. Protection and re-establishment of glossy blackcockatoo habitat in South Australia: Evaluation and recommendations. Unpublished Report: South Australian National Parks Foundation, Glossy Black Cockatoo Rescue Fund. Garnett, S.T.; Pedler, L.P.; Crowley, G.M. 1999. The breeding biology of the Glossy Black-cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami on Kangaroo Island, South Australia. Emu 99: 262-279. Garnett, S.T. and G.M. Crowley (2000). The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000. Canberra, ACT, Environment Australia. Harris, J.B.C.; Fordham, D.A.; Mooney, P.A.; Pedler, L.P.; Araújo, M.B.; Paton, D.C.; Stead, M.G.; Watts, M.J.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Brook, B.W. 2012. Managing the long-term persistence of a rare cockatoo under climate change. Journal of Applied Ecology 49: 785-794. Joseph, L. 1982. The Glossy Black Cockatoo on Kangaroo Island. Emu 82: 46-49. Joseph, L. 1989. The Glossy Black-cockatoo in the South Mount Lofty Ranges. South Australian Ornithologist 30: 202-204. Mooney, P.A.; Pedler, L.P. 2005. Recovery plan for the South Australian subspecies of the Glossy Blackcockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus): 2005-2010. Unpublished Report: South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage. Morgan, D.; Barth, M. 2013. The South Australian subspecies of the glossy black-cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus Recovery Program status review of progress towards the Recovery Plan Objectives 2005 – 2012. Natural Resources Kangaroo Island. Pepper, J.W. 1992. An assessment of the November 1991 fire on the Glossy Black-cockatoo in Flinders Chase National Park. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Adelaide, South Australia. Pepper, J.W. 1997. A survey of the South Australian Glossy Black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus) and its habitat. Wildlife Research 24: 209-223. Schodde, R.; Mason, I.J.; Wood, J.T. 1993. Geographical differentiation in the glossy black-cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus lathami (Temminck), and its history. Emu 93: 156-166. 13 Box 1. Guidelines for assessing the conservation status of the South Australian subspecies of the Glossy Black-cockatoo under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Several criteria are used to objectively establish a species’ conservation status in Australia which are based on: 1) the likelihood of the species undergoing a reduction in numbers in the future, 2) the extent of the species’ geographic distribution, 3) the estimated number of mature individuals, and 4) the probability of the species becoming extinct over different timeframes (ranging from 10 – 50% in the immediate future) (EPBC Act 1999). These criteria are based on the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (IUCN 2001). Threshold values for each criterion have been described, and a species’ conservation status is based on the most conservative. For example, a species may have populations containing numerous mature individuals; however, if these are being severely reduced at a rate of ≥70% over the preceding 10 year period, a status of Endangered would be listed. To shift the conservation status of the GBC from Endangered to Vulnerable, the primary criterion at present is the number of mature individuals. Endangered species are those with 50 – 249 mature individuals while Vulnerable species have 250 – 999 in their population (assuming there is an equal gender ratio). For the GBC a gender bias exists and there are approximately 1.3 males for every female (Morgan and Barth 2013). The main method used by the GBC RP to determine population numbers is an annual census at the completion of the breeding season in late September or early October (Mooney and Pedler 2005). Demographical data from these censuses has established that ca. 79% of the population are mature individuals while 21% are juveniles (Morgan and Barth 2013) Accordingly, a population size of at least 350 birds would need to exist (i.e. 125 mature females, 160 mature males and 75 juveniles) in order for the species to alter its conservation status to Vulnerable. 14