Capital Budgeting Decision Rules

advertisement

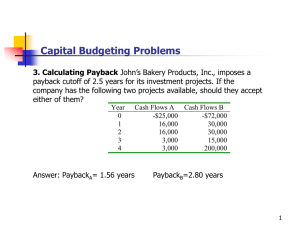

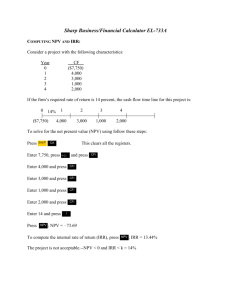

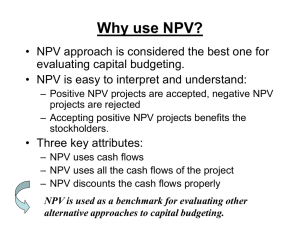

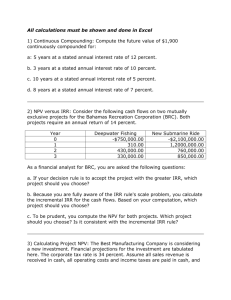

Capital Budgeting Decision Rules What real investments should firms make? Alternative Rules in Use Today NPV IRR Profitability Index Payback Period Discounted Payback Period Accounting Rate of Return What Provides Good Decision-Making? Our work has shown that several criteria must be satisfied by any good decision rule: The decision rule must be based on cash flow. The rule should incorporate all the incremental cash flows attributable to the project. The rule should discount cash flows appropriately taking into account the time value of money and properly adjusting for the risk inherent in the project. - Opportunity cost of capital. When forced to choose between projects, the choice should be governed by maximizing shareholder wealth given any relevant constraints. NPV Analysis The recommended approach to any significant capital budgeting decision is NPV analysis. NPV = PV of the incremental benefits – PV of the incremental costs. NPV based decision rule: When evaluating independent projects, take those with positive NPVs, reject those with negative NPVs. When evaluating interdependent projects, take the feasible combination with the highest combined NPV. Lockheed Tri-Star As an example of the use of NPV analysis we will use the Lockheed Tri-Star case. To examine the decision to invest in the TriStar project, we first need to forecast the cash flows associated with the Tri-Star project for a volume of 210 planes. Then we can ask: What is a valid estimate of the NPV of the Tri-Star project at a volume of 210 planes as of 1967. Internal Rate of Return Definition: The discount rate that sets the NPV of a project to zero (essentially project YTM) is the project’s IRR. IRR asks: “What is the project’s rate of return?” Standard Rule: Accept a project if its IRR is greater than the appropriate market based discount rate, reject if it is less. Why does this make sense? For independent projects with “normal cash flow patterns” IRR and NPV give the same conclusions. IRR is completely internal to the project. To use the rule effectively we compare the IRR to a market rate. IRR – “Normal” Cash Flow Pattern Consider the following stream of cash flows: 0 -$1,000 1 $400 2 $400 3 $400 Calculate the NPV at different discount rates until you find the discount rate where the NPV of this set of cash flows equals zero. That’s all you do to find IRR. IRR – NPV Profile Diagram Evaluate the NPV at various discount rates: Rate 0 10 20 NPV $200 -$5.3 -$157.4 At r = 9.7%, NPV = 0 250 200 150 100 NPV 50 0 -50 0 -100 -150 -200 10 20 Discount Rate The Merit to the IRR Approach The IRR can be interpreted as the answer to the following question. Suppose that the initial investment is placed in a bank account instead of this project. What interest rate must the bank account pay in order that we may make withdrawals equal to the cash flows generated by the project? As with NPV, the IRR is also based on incremental cash flows, does not ignore any cash flows, and (by comparison to the appropriate discount rate, r) accounts for the time value of money and risk (the opportunity cost of capital). In short, it can be useful. Pitfalls of the IRR Approach Multiple IRRs There can be as many solutions to the IRR definition as there are changes of sign in the time ordered cash flow series. Consider: 0 1 2 -$100 $230 -$132 This can (and does) have two IRRs. Pitfalls of IRR cont… Disc.Rate 0.00% 10.00% 15.00% 20.00% 40.00% NPV -$2.00 $0.00 $0.19 $0.00 -$3.06 IRR1 IRR2 0.5 0 NPV -0.5 0 10 15 -1 -1.5 -2 -2.5 -3 Discount Rate 20 40 Pitfalls of IRR cont… 3 2.5 NPV 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 0 10 15 Discount Rate 20 40 Pitfalls of IRR cont… Mutually exclusive projects: IRR can lead to incorrect conclusions about the relative worth of projects. Ralph owns a warehouse he wants to fix up and use for one of two purposes: A. B. Store toxic waste. Store fresh produce. Let’s look at the cash flows, IRRs and NPVs. Mutually Exclusive Projects and IRR Project A B Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 -10,000 10,000 1,000 1,000 -10,000 1,000 1,000 12,000 Project NPV @ 0% $2000 $4000 A B NPV @ NPV@ 10% 15% $669 $109 $751 -$484 IRR 16.04% 12.94% 5000 A B 4000 NPV 3000 2000 1000 0 -1000 0% 10% 15% Discount Rate At low discount rates, B is better. At high discount rates, project A is a better choice. But A always has the higher IRR. A common mistake to make is choose A regardless of the discount rate. Simply choosing the project with the larger IRR would be justified only if the project cash flows could be reinvested at the IRR instead of the actual market rate, r, for the life of the project. Summary of IRR vs. NPV IRR analysis can be misleading if you don’t fully understand its limitations. For individual projects with a normal cash flow pattern NPV and IRR provide the same conclusion. For projects with inflows followed by outlays, the decision rule for IRR must be reversed. For Multi-period projects with several changes in sign of the cash flows multiple IRRs exist. Must compute the NPVs to see what is appropriate decision rule. IRR can give conflicting signals relative to NPV when ranking projects. I recommend NPV analysis, using others as backup. Profitability Index Definition: The present value of the cash flows that accrue after the initial outlay divided by the initial cash outlay. Rule: Take any/only projects with a PI>1. The PI does a benefit/cost (bang for the buck) analysis. When the PV of the future benefits is larger than the current cost PI > 1. If this is true what is true of the NPV? Thus for independent projects the rules make exactly the same decision. N PI t CF /( 1 r ) t t 1 CF0 PI and Mutually Exclusive Projects Example: Project CF0 CF1 NPV @ 10% PI A -$1,000 $1,500 $364 1.36 B -$10,000 $13,000 $1,818 1.18 Since you can only take one and not both the NPV rule says B, the PI rule would suggest A. Which is right? The projects are mutually exclusive so the NPV of one is an opportunity cost to the other. We must take B; in this respect A has a negative NPV. PI treats scale strangely. It measures the bang per buck invested. This is larger for A but since we invest more in B it will create more wealth for us. Payback Period Rule Frequently used as a check on NPV analysis or by small firms or for small decisions. Payback period is defined as the number of years before the cumulative cash inflows equal the initial outlay. Provides a rough idea of how long invested capital is at risk. Example: A project has the following cash flows Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 -$10,000 $5,000 $3,000 $2,000 $1,000 The payback period is 3 years. Is that good or bad? Payback Period Rule An adjustment to the payback period rule that is sometimes made is to discount the cash flows and calculate the discounted payback period. This “new” rule continues to suffer from the problem of ignoring cash flows received after an arbitrary cutoff date. If this is true, why mess up the simplicity of the rule? Simplicity is its only virtue. At times the payback or discounted payback period may be valuable information but it is not often that this information alone makes for good decisionmaking. Average Accounting Return Definition: The average net income after depreciation and taxes (before interest) divided by the average book value of the investment. Rule: If the AAR is above some cutoff take the project. This is essentially a measure of return on assets (ROA). AAR Issues Doesn’t use cash flows but rather accounting numbers. Ignores the time value of money. Does not adjust for risk. Uses an arbitrarily specified cutoff rate. Other than that it’s a beautiful decisionmaking tool. Applying the NPV Method While other approaches (particularly IRR) can be of use, I recommend NPV. The three steps to apply NPV: Estimate the incremental cash flows (today). Select the appropriate discount rate to reflect current capital market conditions and risk. Compute the present value of the cash flows. For now, we will continue to assume that firms are all equity financed. To be continued… Our Golden Rules (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) Cash flows are the concern. Consider only incremental cash flows. Don’t forget induced changes in NWC. Don’t ignore opportunity costs. Never, never, never neglect taxes. Don’t include financing costs in cash flow. Treat inflation consistently. Recognize project interactions. Incremental Cash Flow The incremental cash flow is the company’s total free cash flow with the proposed project minus the company’s total cash flow without the project. Some issues that arise: Sunk costs. These are costs, related to the project, that have already been incurred. Opportunity costs. What else could be done? Capital expenditures versus depreciation expense. Side effects. Does the new project affect other cash flows of the firm? Taxes. Increased investment in working capital. Sunk Costs vs. Opportunity Costs Last year, you purchased a plot of land for $2.5 million. Currently, its market value is $2.0 million. You are considering placing a new retail outlet on this land. How should the land cost be evaluated for purposes of projecting the cash flows that will become part of the NPV analysis? Side Effects A further difficulty in determining cash flows from a project comes from effects the proposed project may have on other parts of the firm. The most important side effect is called erosion. This is cash flow transferred from existing operations to the project. Chrysler’s introduction of the minivan. What if a competitor would introduce the new product if your company does not? Taxes Typically, Revenues are taxable when accrued. Expenses are deductible when accrued. Capital expenditures are not deductible, but depreciation can be deducted as it is accrued, tax depreciation can differ from that reported on financial statements. Sale of an asset for a price other than its tax basis (original price less accumulated tax depreciation) leads to a capital gain/loss with tax implications. Working Capital Increases in Net Working Capital should typically be viewed as requiring a net cash outflow. increases in inventory and/or the cash balance* require actual uses of cash. increases in receivables mean that accrued revenues exceed actual cash collections. If you are basing your measure of cash flow on accrued revenues you need a correcting adjustment. If you are basing your measure of cash flow on cash revenues no adjustment is required.