Budgeting and Long Term Planning

advertisement

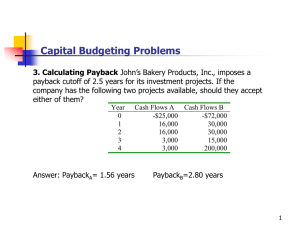

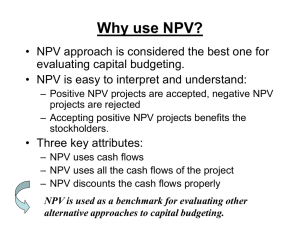

MODULE 11 BUDGETING AND LONG TERM PLANNING ADB Private Sector Development Initiative Corporate and Financial Governance Training Solomon Islands Originally by Dr Judy Taylor Acknowledgement These materials were produced by Dr Judy Taylor from La Trobe University, through the Asian Development Bank’s Pacific Private Sector Development Initiative (PSDI). PSDI is a regional technical assistance facility co-financed by the Asian Development Bank, Australian Aid and the New Zealand Aid Programme. Module 11 Outline What is Capital budgeting Steps in capital budgeting Capital budgeting techniques explained Payback Net present value Internal rate of return Accounting return How do I choose which project to implement Capital Budgeting Capital budgeting is the formal term for planning long-term investment decisions. These projects are different from normal budgeting decisions due to their size and the time taken to implement them. The problem for the business is threefold, how to evaluate a project, when they have a number of such projects they can undertake how do they evaluate them and then how to compare them. Capital Budgeting Techniques can be used to help a company to assess if the capital budgeting proposals will yield a return and deliver an economic value to the company. usually focus on the cash flows of the investment choices rather than accounting profit. Module 8, we constructed a budget for our business. Capital budgeting decisions require the company to complete similar forecasts of costs as well as cash flows in and out when evaluating a business proposal. These projects should be found in the long term business plan, but they will be planned for and evaluated separately. Capital Budgeting If there is more than one project that the company is considering the company should evaluate all the projects in the same manner. Firstly estimating the costs then the cash flow. Taking care to allocate each of these to the correct period. Capital Budgeting Once the capital budgeting is undertaken for all the proposed projects the company must make a decision of which project they will undertake. companies usually have access to limited resources and are unable to take up every opportunity that presents itself. companies that grow too quickly often fail or suffer loss for a period of time because they stretch their management resources too thinly and it takes resources to integrate new business into the old business structure. So even if it is possible to undertake a number of projects it is often not wise to do so. Capital Budgeting Steps involved in capital budgeting. 1. Identify long-term goals of the individual or business. 2. Identify potential investment proposals 3. Estimate and analyse the relevant cash flows of the investment 4. Determine financial feasibility of each of the investment proposals using the capital budgeting methods. 5. Choose the projects to implement 6. Implement the projects chosen 7. Monitor the projects implemented. Capital Budgeting Different projects have different timings of cash outflows and inflows. There are a number of techniques that a company can use to evaluate the projects. Each potential project needs to be evaluated. This can be done either calculating the amount of time it takes to have your investment funds returned, or converting the cash inflows and outflows into current dollars. Assume the following 4 projects are available for your company to undertake. 4 different projects Project 1 Project 2 4 different projects Project 3 Project 4 4 different projects Which project is better? Why? How do you evaluate the different timing of the cash inflows and outflows? Capital budgeting decisions Understanding how the different methods for assessing capital investments are calculated, is critical to making a sound responsible choice (even though staff will usually do it for the board). Understanding discount rates and the time value of money is central to this solid understanding A dollar received in a year from today is not as valuable as a dollar received today, its value is discounted by time - I year Capital budgeting decisions If the dollar received today could be invested and earn 10%, then in a year it will be worth $1.10, But, the dollar we receive is a year will just that $1. To find the value of a dollar that will be received in the future we discount it by the rate it could have earned, 10%. So 1/1.10 =$.909. And $ .909 invested at 10% for I year will grow to $1. That shows us that in todays terms a dollar received today is worth $1 but a dollar received in in year is worth only $.909 cents today This is why we prefer a dollar today and why discounting future cash flows to todays value helps us make sound responsible financial investment decisions. Capital budgeting decisions If we discount by a set amount say 10% to find the value of a dollar received in the future to a present value $, the dollar value of the discounted sums is called the net present value, NPV If we discount so that the NPV = 0 this is called the internal rate of return. Capital Budgeting These techniques include: Payback Period Discounted Payback Net Present value Internal rate of return Modified internal rate of return Accounting rate of Return How do I do this, Which one should I use, and Why? Payback Period The payback period calculates how long it takes to have your investment returned to you in years, or months. This is the simplest method for assessing a projects return. Using Project 1 above Year 0 1 2 3 Cash Flow -$40,000 -$40,000 $110,000 $130,000 Cumulative cash flows -$40,000 -$80,000 $30,000 $160,0000 It took 2. 72 years to receive cash flows sufficient to return the capital invested. Decision Rule The project that pays back in shortest time is most desirable. Discounted Payback Period The payback does not distinguish the future dollars from todays dollars. A dollar received in 4 years hence is worth less than a dollar received today. We can discount the future values by a discount rate, say 10% and recalculate the payback based on the more realistic values. Year Cash Flow Discount rate Discounted value Cumulative Cash Flows 0 -$40,000 0 -40000 -$40,000 1 -$40,000 1.1 -36,366 -$76,366 2 2 $110,000 (1.1) 90909.9 +$14543 3 3 $130,000 (1.1) This gives a payback in 2.84 years as opposed to 2.72. Usually the discounted payback takes longer. Decision Rule The project that pays back in shortest time is most desirable. Net Present Value (NPV) This technique estimates the present value of a stream of cash inflows and outflows over different time periods. If the NPV is greater than zero then the project is viable. It discounts cash inflows and outflows using a discount rate, to find its NPV. This technique was first used in 1951. Today it is the most common method used in financial textbooks and by companies. To undertake a NPV calculation an estimate of the size and timing of all the cash flows as well as an estimate of a discount rate is required. Net Present Value (NPV) Value of NPV Interpretation NPV > 0 the project would add value to the firm the project would not add value to the firm the project would neither add nor lose value for the firm Action the project may be accepted NPV < 0 the project should be rejected NPV = 0 as the project neither adds nor subtracts from the value we are indifferent to the project The decision to proceed or reject the project will be based on availability of other projects or other criteria. Net Present Value (NPV) Selecting the proper discount rate is critical to the correct calculation. The NPV is determined by the discount rate, also called the hurdle rate—is crucial to making the right decision. The hurdle rate is the minimum acceptable rate of return on an investment. Net Present Value (NPV) The formula to discount one future cash flow to its present value is: PV = FV/(1+r)n PV= Present value FV = Future value r = discount rate n = number of years Net Present Value (NPV) However where there is more than one future cash flow you use the following formula Or -C0 = Initial Investment C = Cash Flow r = discount rate 1,2,3, n = time Net Present Value (NPV) Looking at project 1. The project incurs cost of $40000 in each of the 4 years, but In year 2 the project earns a net cash inflows for the first time of $110000. In year 3 the project earns a net cash inflow of $1300000. Year 0 1 2 3 Cash Flow -$40,000 -$40,000 $110,000 $130,000 Total costs$160,000 Discount rate 0 1.1 (1.1)2 (1.1)3 Present Value -$40,000 -$36,363.64 $90,909.09 $97,670.92 +$112,216.37 Net Present Value (NPV) Net Present Value = $112,216.37 Net Present Value (NPV) Decision Rule. If at the end the NPV is greater than zero then the project is viable. Discount Rate The discount rate is the rate used to convert the cash flows into todays value, the present value. The rate used should reflect the riskiness of the investment, as well as the volatility of the cash flows. It must also take into account the financing mix, internal, raising capital from owners plus outside financing from banks or bond issuing. Net Present Value (NPV) Different discount rates If the company produces across a number of industry types and the cost of capital is different in each, a different hurdle rate should be used for each project that reflects the risk of each project. A higher discount rate would be used if a project's risk is higher than the risk of the firm as a whole. Net Present Value (NPV) How do you estimate the discount rate? To estimate the cost of the financing mix Managers often use models such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, (CAPM) to estimate the appropriate discount rate for each particular project. CAPM uses the cost of the financing mix - debt plus equity, weighted by their respective share of the total. This is called the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), when it is used as the discount rate to calculate the NPV it is referred to as the hurdle rate. This is because each project must earn a return greater than the cost of capital. If not there is no financial/economic reason to proceed with the project. Net Present Value (NPV) Problems with the NPV Calculations Choosing the discount rate Choosing the correct premium to add as a risk factor to the discount rate. If this is simply based on a bank premium it may be incorrect and result in a misleading indicator of economic value. Depending upon the industry, cash flows at the end of the life of the project may become negative (e.g. if large remediation of the site is required), in areas such as mining. This can be catered for by explicitly allowing for financing the losses- negative cash outflows. The NPV shows you whether your return is above your required return but it does not give you an actual return. In order to calculate this you need to do an IRR calculation. Internal Rate of return The IRR is the rate of return such that the present value equals zero. Internal rate of return and net present value IRR uses a similar technique to the one used in NPV (to convert the future cash flows into present day dollars) except a different discount rate is used. The IRR is the discount rate that gives a NPV of zero. IRR is used as a measure of investment efficiency. Internal Rate of return The IRR method will result in the same decision as the NPV method, (see table below). In the usual cases where a negative cash flow occurs at the start of the project, followed by all positive cash flows projects that have a higher IRR higher than the hurdle rate should be accepted. Nevertheless, for mutually exclusive projects, it is possible that if a company’s decision rule requires them to choose the project with the highest IRR - which is often used – they may be selecting a project with a lower NPV. Internal Rate of return Value of NPV Value of IRR Interpretation/Action NPV > 0 IRR> NPV NPV < 0 IRR<NPV NPV = 0 IRR= NPV the project would add value to the firm the project may be accepted the project would not add value to the firm the project should be rejected The project would neither add nor lose value for the firm As the project neither adds nor subtracts from the value so we are indifferent to the project. The decision to proceed or reject the project will be based on availability of other projects or other criteria. Internal Rate of return To find the IRR we use the same formula as used in NPV but insert a new value for the discount rate. This discount rate is found by trial and error. In our example above we found that the NPV of our project is $112,216 when a hurdle rate of 10% is used. We know the project cost $160,000 and earned $320, 000, so we might start with a discount rate of 45% Internal Rate of return In 2015 the project costs $40000 In 2016 the project costs another $40000 In 2017 the project earns a net cash inflows for the first time of $110000. In 2018 the project earns a net cash inflow of $1300000. Year 0 1 2 3 Total costs Cash Flow -$40,000 -$40,000 $110,000 $130,000 $160,000 Present Value - IRR at 45% -$40,000 -$27,586.21 $52,318.67 $42,642.18 $27,374.64 Internal Rate of return 𝑁𝑃𝑉 = −$40,000 + −$40000 $110000 $130000 + + 1.45 1.452 1.453 Net Present Value = $27,374.64 and an IRR above 45%. Because the NPV is greater than zero dollars we have not found the true IRR. We then keep trying to find the IRR through trial and error. Year 0 1 2 3 Cash Flow -$40,000 -$40,000 $110,000 $130,000 total $160,000 𝑁𝑃𝑉 = −$40,000 + Present Value - IRR at 65% -$40,000 -$24,242 $40,404 $28,940 $5,101 −$40000 $110000 $130000 + + 1.65 1.652 1.653 This is still not zero. It is also a bit misleading. The IRR is unique if one or more years of net investment (negative cash flow) are followed by years of net revenues. However if the signs of the cash flows change more than once, there may be several IRRs. Internal Rate of return Decision Rule If the IRR is greater than the hurdle rate, the required rate of return by your company, then the project is Viable. Internal Rate of return Problems with IRR Calculation Understanding how to interpret the IRR can be problematic. The IRR does not calculate the actual annual profitability of an investment. This is because the intermediate cash flows are not reinvested at the project's IRR, therefore, the actual rate of return will be lower than the IRR calculated. For this reason a Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) is often used. Despite a strong academic preference for NPV, surveys indicate that executives prefer IRR over NPV, although when they are used together they produce the strongest information. In a budgetconstrained environment, efficiency measures should be used to maximize the overall NPV of the firm. Some managers find it intuitively more appealing to evaluate investments in terms of percentage rates of return than dollars of NPV. Modified Internal Rate of Return The MIRR assumes a different finance rate to the IRR For instance in our project the finance rate on our $40,000 investment in years 1 and 2 would be different from our discount or hurdle rate in years 3 and 4. This is intuitively sensible as we expect to earn more on our project than the costs of finance. Modified Internal Rate of Return In our above example we found an IRR above 71%. This is not intuitively realistic. To calculate the MIRR we begin by setting a cost of finance at 10% and a reinvestment rate at 15% We then do our calculating in 3 steps. Step 1. calculate the present value of the negative cash flows (discounted at the finance rate): Step 2. Calculate the future value of positive cash flows Step 3. Calculate MIRR. Modified Internal Rate of Return Year Cash Flow 0 1 2 3 -$40,000 -$40,000 $110,000 $130,000 total costs $160,000 Present Value Future Value at 10% discount at 15% discount -$40,000 -$36,364 $126,500 $130,000 - $76,364 $256,500 Modified Internal Rate of Return Step 1. Present Value of investment Step 2. (110,000*1.15) +130000 = 256,500 Step 3. Calculate the MIRR: = 49.75% this formula can be done in excel or in steps In steps – calculator Step 1 divide 256500/76364 = 3.359 Step 2 use cubic square root function on Step 3 subtract 1 Modified Internal Rate of Return Using the MIRR we get a return of approximately 50%, less than the estimated 71% using IRR, it is a more realistic estimate of our return. Decision Rule If the MIRR is greater than the hurdle rate, the required rate of return by your company, then the project is viable. Accounting Rate of return The ARR, often also referred to as the average rate of return, calculates the accounting profit amount of an investment made. It is calculated by dividing the average profit by the initial investment to get the ratio or return that can be expected. This allows the company to then compare the outcome of this project to other projects. ARR does not take into account the time value of money and for this reason considered to lack the sophistication of NPV or IRR. Accounting Rate of return ARR = Average return during period/ average investment Average Investment = Book value at beginning of year 1 less book value at end/divided by 2 Average return = incremental revenue less incremental expense. Accounting Rate of return Using Project 1 An initial investment of $40,000 in year 1 and 2 is expected to generate cash inflow of $110000 in year 3 and $130000 in year 4. We assume that at the end of the 4 years the machine will be worth $20,000 and we can sell it for this amount. During the projects life we can depreciate the equipment using the straight line basis. We can calculate ARR assuming that there are no other expenses on the project. Annual Depreciation = (Initial Investment − Scrap Value) ÷ Useful Life in Years Annual Depreciation = ($160,000 − $20,000) ÷ 4 ≈ $35000 Average Accounting Income = (110000 +130000)/4 )− 35000 = $25,000 Accounting Rate of Return = $25000÷ $160,000 ≈ 15.6% Accounting Rate of return This method like the payback is simple to calculate, however it ignores the real (time) value of money. It is also common to find it calculated differently and as such consistency can be a problem. Decision Rule Accept project if ARR is equal to, or greater than the required rate of return Capital budgeting decisions technique Accept Reject Not sure Payback Shortest number of years Longest number mid range and strong of years NPV with IRR > NPV Discounted payback Shortest number of years Longest number mid range and strong of years NPV with IRR > NPV Net Present value NPV>0 NPV<0 NPV=0 project neither adds value nor costs the firm Internal rate of return NPV>0 and IRR>NPV NPV<0 IRR<NPV NPV=0 IRR+NPV Modified internal rate of return NPV>0 and MRR>NPV NPV<0 MRR<NPV NPV=0 MRR+NPV Accounting rate of return ARR> required rate of return ARR< required rate of return ARR=required rate of return How do we choose the correct project? Payback Discounted payback NPV IRR MIRR ARR Payback Discounted payback NPV IRR MIRR ARR Return 2.73years 2.84 years Return 3.64 years 3.97 years Return 2.78 years 2.92 year Project 4 Return 2.9 years 3.1years $112,216 71% 50% 28.1% $30,353 11% 11% 6.75% $140,120 52% 40% 30.9% $115,326 40% 34% 35.16% Rank 1 1 Rank 4 4 Rank 2 2 3 1 1 3 4 4 4 4 1 2 2 2 Project 4 Rank 3 3 2 2 3 1 Capital budgeting decisions Project 1 Ranks 1 on 4 methods Payback, Project 2 Ranks 4 under every technique Project 3 Ranks discounted payback, IRR and MIRR 1using NPV only Project 4 Ranks 1 using Accounting rate of return Capital budgeting decisions 1. 2. 3. Project 1 is overwhelmingly the best project using these techniques. It pays back our investment in the shortest time as well as having the highest internal rate of return However this number crunching is only the first step in our review. Does this business sit well with our other businesses? We have used the same hurdle rate on each investment, was this appropriate? What is the actual risk of each of these businesses Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask 4. How well do the proposed businesses fit with our present business, risk appetite and ethics? 5. What are the main risks we need to consider of the alternate projects Strategic Risk: A possible source of loss that might arise from the pursuit of an unsuccessful business plan Financial Risk: is an umbrella term for multiple types of risk associated with financing, including financial transactions that include company loans in risk of default. Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask Regulatory Risk2. is the risk of a change in regulations and law that might affect an industry or a business. Systematic Risk risk of collapse of an entire financial system or entire market, as opposed to risk associated with any one individual entity, or group. Process Risk: Probability of loss inherent in business processes. The risk that a manufacturing company might produce contaminated food. 2. The definitions for the risk have been taken from Wikipedia, unless stated otherwise Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask Legal Risk The risk of financial or reputational loss arising from: regulatory or legal action; disputes for or against the company; failure to correctly document, enforce or adhere to contractual arrangements; inadequate management of non-contractual rights; or failure to meet non-contractual obligations changes to laws affecting your business2 the cost and loss of income caused by legal uncertainty, multiplied by possibility of the individual event or legal environment as a whole.3 2. Kevin Johnson and Zane Swanson "Legal Risk in the Financial Markets" Management Accounting Quarterly, Full 2007 3.Tat Chee Tsui. "Experience from the Anti-Monopoly Law Decision in China (Cost and Benefit of Rule of Law)." The Network: Business at Berkeley Law (Apr/ May 2013) Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask Operational Risk is "the risk of a change in value caused by the fact that actual losses, incurred for inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems, or from external events (including legal risk), differ from the expected losses". Basel II: Revised international capital framework". Bis.org. Retrieved 2013-06-06. Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask Reputational Risk: is a risk of loss resulting from damages to a firm's reputation, in lost revenue; increased operating, capital or regulatory costs; or destruction of shareholder value consequent to an adverse or potentially criminal event even if the company is not found guilty. Adverse events typically associated with reputation risk include ethics, safety, security, sustainability, quality, and innovation. Reputational risk can be a matter of corporate trust. (Wikipedia) Risk – Questions Directors Need to Ask 6. What are we doing to measure and assess these? 7. What can we learn from the experience of others? A report by the financial subcommittee on capital budgeting will include a discussion of each of these areas as well as capital budgeting techniques. Only when the returns and risks are reviewed together can the company make a decision.