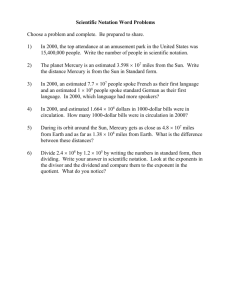

Project Mercury When was Project Mercury founded?

advertisement

Project Mercury When was Project Mercury founded? • Project Mercury was founded on October 7, 1958. Mercury’s Goals • Started in 1958 and completed in 1963, Project Mercury was the United States' first man-inspace program. The main objectives of the program, which made six manned flights from 1961 to 1963, were specific: • To orbit a manned spacecraft around Earth • To investigate man's ability to function in space • To recover both man and spacecraft safely How long did Project Mercury last? • Project Mercury lasted for about 4 2/3 years. The Mercury 7 The Seven Astronauts • In the Mercury program, there were originally seven astronauts but, since one of them had a health issue only six of the seven flew. • The seven astronauts were: – – – – – – – Walter M. Schirra, Jr. Donald K. Slayton John H. Glenn, Jr. Scott Carpenter Alan B. Shepard, Jr. Virgil I. (“Gus”) Grissom L. Gordon Cooper. Facts about the Mercury Capsule • The Mercury space capsule was incredibly tiny. • The size of it on the outside was about the size of a compact car, but in the inside, it is smaller than a telephone booth. • One astronaut said that the interior of the Mercury capsule was about the same size as a coffin. • The bell-shaped Mercury capsule had a diameter of 6 feet. • The length of the capsule was 9 ½ feet. Who was in charge? • The people that were in charge of the astronauts was Mission Control (over in Cape Canaveral, Florida and later flights: Houston, Texas). • But, in each mission, one astronaut was picked to be in charge of his crew. When did the first Mercury Project rocket launch? • “Mission: Little Joe 1 Launch Pad: Wallops Island Pad Vehicle: Little Joe (1) Crew: Unmanned Milestones: Not applicable Payload: Boiler Plate Capsule Mission Objective: Max Q abort and escape test. Objective was to determine how well the escape rocket would function under the most severe dynamic loading conditions anticipated during a Mercury-Atlas launching.” When did the first Mercury Project rocket launch? (continued) • “Orbit: Altitude: .4 statute miles Orbits: 0 Duration: 0 Days, 0 hours, 0 minutes, 20 seconds Distance: .5 statute miles Launch: At 35 minutes before launch, evacuation of the area had been proceeding on schedule and the batteries for the programmer and destruct system in the test booster were being charged. Suddenly, half an hour before launch time, an explosive flash occurred. When the smoke cleared it was evident that only the capsule-andtower combination had been launched, on a trajectory similar to an off-the-pad abort. The booster and adapter-clamp ring remained intact on the launcher. Near apogee, at about 2000 ft, the clamping ring that held tower to capsule released and the little pyro-rocket for jettisoning the tower fired.” When did the first Mercury Project rocket launch? (continued) • “The accident report for LJ-1, issued September 18, 1959, blamed the premature firing on the Grand Central escape rocket on an electrical leak, or what missile engineers call transients or ghost voltages in a relay circuit. The fault was found in a coil designed to protect biological specimens from too rapid an abort. (Reference SP-4201 p. 208) Landing: Not applicable” Other launches after Shepard • Mercury astronauts Alan Shepard and Virgil "Gus" Grissom flew earlier suborbital flights. • Glenn was the first to orbit. He was soon followed into orbit by colleagues Carpenter, Schirra and Gordon Cooper. • Deke Slayton was grounded by a medical condition until the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. The Launch • “Launch: February 20, 1962. 9:47:39 am EST. Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 14. Powered flight lasted 5 minutes 1 second and was completed normally. The mercury countdown began on 1/27/62 and was performed in two parts. Precount checks out the primary spacecraft systems, followed by a 17.5 hour hold for pyrotechnic checks, electrical connections and peroxide system servicing. Then the countdown began. The launch countdown proceeded to the T-13 minute mark and then was canceled due to adverse weather conditions. After cancellation, the mission team decided to replace the carbon dioxide absorber unit and the peroxide system had to be drained and flushed to prevent corrosion. Launch vehicle systems were then revalidated and a leak was discovered in the inner bulkhead of the fuel tank that required 4-6 days to repair. The launch was rescheduled to 2/13/62 and then to 2/14/62 to all the bulkhead work to complete. The precount picked up again on 2/13/62, 2/15/62 and 2/16/62 but was canceled each time due to adverse weather. The launch was then rescheduled for 2/20/62.” The Launch (continued from previous slide) • “During the launch countdown on 2/20/62, all systems were energized and final overall checks were made. the count started at T-390 minutes by installing and connecting the escape-rocket igniter. The service structure was then cleared and the spacecraft was powered to verify no inadvertent pyrotechnic ignition. The personnel then returned to the service structure to prepare for static firing of the reaction control system at T-250 minutes. The spacecraft was then prepared for boarding at T-120 minutes. The hatch was put into place at T-90 minutes. During installation a bolt was broken, and the hatch had to be removed to replace the bolt causing a 40 minute hold. From T-90 to T-55 final mechanical work and spacecraft checks were made and the service was evacuated and moved away from the launch vehicle. At T-45 minutes, a 15 minute hold was required to add fuel to the launch vehicle and at T-22 minutes and additional 25 minutes was required for filling the liquid-oxygen tanks as a result of a minor malfunction in the ground support equipment used to pump liquid oxygen into the launch vehicle. At approximately T-35 minutes, filling of the liquid-oxygen tanks began and final spacecraft and launch vehicle systems checks were started. At T-10 minutes the spacecraft went on internal power. At T-6min 30 seconds, a 2 minute hold was required to make a quick check of the network computer at Bermuda. The launch vehicle went on internal power at T-3 minutes. At T-35 seconds the spacecraft umbilical was ejected and at T-0 the main engines started. Liftoff occurred at T+4 seconds at 9:47:39am EST. ” What did the astronauts have to do in order to prepare for the challenge? • “On October 7, 1958, the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) announced Project Mercury, its first major undertaking. The objectives were threefold: to place a human spacecraft into orbital flight around Earth, observe human performance in such conditions, and recover the human and the spacecraft safely. At this early point in the U.S. space program, many questions remained. Could a human function ably as a pilot-engineer-experimenter in the harsh conditions of weightless flight? If yes, who were the right people for the challenge? • The selection procedures for Project Mercury were directed by a NASA selection committee, consisting of Charles Donlan, a senior management engineer; Warren North, a test pilot engineer; Stanley White and William Argerson, flight surgeons; Allen Gamble and Robert Voas psychologists; and George Ruff and Edwin Levy, psychiatrists. The committee recognized that the unusual conditions associated with spaceflight are similar to those experienced by military test pilots. In January 1959, the committee received and screened 508 service records of a group of talented test pilots, from which 110 candidates were assembled. Less than one month later, through a variety of interviews and a battery of written tests, the NASA selection committee pared down this group to 32 candidates.” What did the astronauts have to do in order to prepare for the challenge? • “Each candidate endured even more stringent physical, psychological, and mental examinations, including total body x-rays, pressure suit tests, cognitive exercises, and a series of unnerving interviews. Of the 32 candidates, 18 were recommended for Project Mercury without medical reservations. On April 1, 1959, Robert Gilruth, the head of the Space Task Group, and Donlan, North, and White selected the first American astronauts. The "Mercury Seven" were Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., John H. Glenn, Jr., Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr., and Donald K. "Deke" Slayton. • At a press conference in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 1959, NASA introduced the Mercury Seven to the public. The press and public soon adopted them as heroes, embodying the new spirit of space exploration. Each one (except Slayton, who was grounded because of a previously undiscovered heart condition, but later flew as a crewmember of the Apollo Soyuz Test Project) successfully flew in Project Mercury. During the five-year life of the project, six human-tended flights and eight automated flights were completed, proving that human spaceflight was possible. These missions paved the way for the Gemini and Apollo programs as well as for all further human spaceflight.” The Atlas Rocket Mission Control Mercury Capsule Photos Mercury 6 Glenn Enters Friendship 7 Mercury 3 Shepard Recovery Mercury 6 Capsule Retrieval Mercury 4 Recovery Attempt Mercury 9 Cooper Enters Faith 7 Pictures from Project Mercury John Glenn (MA-6) Leaves Crew Quarters Wally Schirra (MA-8) T-38 Mercury Seven with Convair 106-B Alan Shepard (MR-3) Launch Mission Insignia The recovery of the Freedom 7 Alan Shepard’s space patch Shepard and his capsule are recovered Launch of the Mercury-Redstone 3 spacecraft on May 5, 1961, 9:34 a.m. EST, with Alan Shepard onboard. Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. Alan Shepard in his astronaut suit Grissom in front of his Liberty Bell 7 Capsule Grissom’s Insignia Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom’s space suit on display at Grissom the Astronaut Hall of Fame Grissom in his astronaut suit Grissom as a USAF pilot before becoming an astronaut Carpenter inspecting his capsule Carpenter’s Insignia Malcolm Scott Carpenter Scott Carpenter in a test/practice to prepare for his flight Scott Carpenter as an astronaut The Apollo Soyuz. Slayton’s Insignia Donald Kent "Deke" Slayton Donald Kent “Deke” Slayton Donald Slayton in his space suit. Launch of the Saturn IB rocket carrying the Apollo Command Module into orbit. Walter Marty Schirra, Jr. March 10, 1966, Wally Schirra is presented with the Philippine Air Force Aviation Badge by Imelda Marcos as Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, watches. Schirra is also wearing the Philippines’ Legion of Honor, presented in a ceremony at the Malacañang Palace in Manila Walter Schirra is with his Mercury capsule Walter Schirra in his space suit F3H Demon delivery, mid 1950s Walter Schirra’s Insignia John Glenn standing in front of his capsule John Glenn’s Insignia John Herschel Glenn Jr. Mercury 6 Inspecting Decal John Glenn as a USMC pilot MA-9 launch Cooper’s picture of Tibet from space Cooper in an SSTV broadcast from Faith 7 Leroy Gordon Cooper Cooper’s Mercury Faith 7 Mission patch Leroy Gordon Cooper “Friendship 7 Pad LC-14 Atlas (6) Crew: John H. Glenn, Jr. Milestones: 8/27/61 - Capsule arrived at Cape Canaveral 2/15/62 - Flight Safety Review 2/20/62 - Launch Payload: Spacecraft No. 13, Vehicle Number 109-D Mission Objective: Place a man into earth orbit, observe his reactions to the space environment and safely return him to earth to a point where he could be readily found. The Mercury flight plan during the first orbit was to maintain optimum spacecraft attitude for radar tracking and communication checks. Orbit: Altitude: 162.2 x 100 statute miles Inclination: 32.54 Orbits: 3 Period: 88min 29sec Duration: 0 Days, 4 hours, 55 min, 23 seconds Distance: 75,679 statute miles Velocity: 17,544 mph Max Q: 982 psf Max G: 7.7 ” Scott Carpenter “In November 1951, he was assigned to Patrol Squadron 6 based at Barbers Point, Hawaii. During the Korean conflict, he was with Patrol Squadron 6 engaged in anti-submarine patrol, shipping surveillance and aerial mining activities in the Yellow Sea, South China Sea and the Formosa Straits.4 In 1954 he entered the Navy Test Pilot School at the Naval Air Test Center, Patuxent River, Maryland. After completion of his training, he was assigned to the Electronics Test Division of the NATC. In this assignment Carpenter conducted flight test projects with the A3D, F11F and F9F and assisted in other flight test programs.5 He flew tests in a variety of Naval aircraft including multiand single-engine jet aircraft and propeller-driven fighters, attack planes, patrol bombers and seaplanes.6 He then attended Naval General Line School at Monterey, California, for ten months in 1957 and the Naval Air Intelligence School, Washington, DC for an additional eight months in 1957 and 1958. In August 1958 he was assigned to the USS Hornet, anti-submarine aircraft carrier, as Air Intelligence Officer, where he was serving when he received cryptic orders to report to Washington in connection with an unspecified special project.7 Stopping in an airport on the way back from Washington, he picked up a Time magazine and learned that the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had identified 110 candidates, all military pilots, from which to take volunteers for America's first manned venture into space. A few weeks later he became one of the "Original Seven" Mercury astronauts, chosen on April 9 1959, and was assigned to the Manned Spacecraft Center (then Space Task Group) at Langley Field, Virginia.8 Upon reporting for duty, he was assigned a specialty area in training involving communications and navigational aids, because of his extensive prior experience in that field in the Navy. He served as John Glenn's backup pilot during pre-flight preparations for America's first manned orbital flight, MA-6.9 When NASA grounded MA-7 pilot Donald K. Slayton (Deke) due to his heart condition, idiopathic atrial fibrillation (erratic heart rate), Carpenter was selected as prime pilot for that mission with Walter M. Schirra, Jr., as his backup pilot.” Donald K. “Deke” Slayton “On April 9, 1959, Slayton joined fellow Mercury astronauts, Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, John H. Glenn, Jr., M. Scott Carpenter, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., and L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., for a press conference in Washington, D.C., to announce to the press and the world that the United States had officially joined the "space race." Following the press conference, the astronauts returned to Langley to begin their intensive training. This included a "little of everything" ranging from a graduate-level course in introductory space science to simulator training and scuba-diving. Training continued until the Langley Space Task Force was transferred to the newly established Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas.11 When each of the Mercury astronauts were assigned a different portion of the project and special assignments, to ensure pilot input, Slayton's primary assignment was to gain thorough familiarity with the Atlas missile that was to hurl the Mercury capsule into earth orbit. He was intended to be the first American astronaut to orbit the earth, after a planned third suborbital flight by Glenn. But, following the flights of Shepard and Grissom, Glenn's suborbital flight was canceled. He was reassigned to the first orbital Mercury flight and Slayton, on November 29, 1961, was named as the pilot of Mercury Atlas-7 (MA-7), the second orbital mission.12 On March 15, 1962, NASA announced that a heart condition called idiopathic atrial fibrillation (an erratic heart rate) that was first detected in November 1959, would prevent Slayton from making the flight. Carpenter was, at that time, named as the MA-7 replacement with Schirra as his backup pilot.13 The MA-7 mission was successfully completed on May 24, 1962.14 On July 11, 1962, Slayton assumed new operational, engineering and planning responsibilities within NASA's Manned Space Flight Research Programs, including Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. He continued to participate in the astronaut training program and his physical condition was monitored on a continuous basis by members of the MSC medical staff.15 In September 1962, Slayton was assigned as Coordinator of Astronaut Activities with responsibility for directing the newly formed Astronaut Office. In November 1963, he resigned his commission as an Air Force major and continued and continued with NASA as a civilian astronaut. For three years Slayton served as assistant director of flight crew operations, a new office with responsibility for directing the Astronaut Office, Aircraft Operations Office and Flight Crew Support Division. Beginning in 1966, he served as director of flight crew operations. As director of flight crew operations, he played a key role in choosing the crew of every manned space mission, including the Apollo teams.16” Walter Schirra “Schirra was named as one of the "Original Seven" Mercury Astronauts on April 9, 1959. NASA announced that the seven men, Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, John H. Glenn, Jr., M. Scott Carpenter, Schirra, L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., and Donald K. "Deke" Slayton, had been selected from among 110 of the nation's top military test pilots to train as astronauts for Project Mercury, the first phase of the U.S. space program, involving one-man suborbital and orbital missions. Schirra, Shepard and Carpenter were from the Navy; Grissom, Cooper, and Slayton were from the Air Force; and Glenn was from the Marine Corps.10 Schirra's special responsibility in Project Mercury was the development of environmental controls or life-support systems that would ensure the safety and comfort of the astronaut within the spacecraft during the mission. His tasks also included the testing and improvement of the pressurized suit worn by the astronauts.11” Alan Shepard “In 1959 the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) invited 110 top test pilots to volunteer for the manned space flight program. When NASA sent out bids to 110 test pilots, asking them to volunteer, Shepard was disappointed because he did not receive an invitation. It turned out later that his name had been among the 110, but his invitation had been misplaced.13 Of the original 110, Shepard was among the seven chosen for Project Mercury and presented to the public at a press conference on April 9, 1959, held in the ballroom of the historic Dolley Madison House, NASA's temporary headquarters on Lafayette Square.14 The other six were Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom, John H. Glenn, Jr., Donald K. (Deke) Slayton, Malcolm S. (Scott) Carpenter, Walter M. (Wally) Schirra, Jr., and L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. These seven were subjected to an unprecedented and grueling training in the sciences and in physical endurance. Every conceivable situation the men would encounter in space travel was studied and, when possible, simulated with training devices.15 Shepard quickly established himself as a first-rate pilot and engineer. When it came time to split up the technical work Shepard, with his experience with ships and Navy headquarters people, concentrated on the tracking range and the recovery teams needed to pull the astronauts and their spacecrafts out of the water after flight.16 On February 21, 1961, Robert Gilruth, the director of Project Mercury, announced that the there was to be a meeting of only the seven Mercury astronauts and himself at their headquarters at Langley. It was at this meeting that it was announced that Shepard would be the prime pilot for the first mission and Glenn would be his backup pilot. However, the actual choice was not made public until shortly before the launch for fear of having to go to the backup at the last moment. The public was informed that the choice of the first American in space had been narrowed down to Shepard, Grissom and Glenn.17 The announcement that Shepard would definitely be the first American into space came on May 2, 1961, after the first launch attempt was scrubbed due to weather.18 On May 5, 1961, only 23 days after Yuri A. Gagarin of the Soviet Union became the first man in space, Shepard was launched at 9:34am EST aboard the spacecraft he named Freedom 7 (MR-7) powered by a Redstone booster (MR-3).19 He was launched suborbitally to an altitude of over 116 miles, 303 statute miles down range from Cape Canaveral. His 15 minute 28 second flight achieved a velocity of 5,134 miles per hour and pulled a maximum of 11G's.20 Freedom 7 splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean where the aircraft carrier Lake Champlain awaited his arrival. The capsule came through the entire flight in such excellent shape that the engineers who went over it with a fine-tooth comb decided that it could easily be used again.21 The doctors also assessed that the commander was in excellent shape, physically and psychologically and "...could be used again too." Virgil Grissom “Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom had been part of the U.S. manned space program since it began in 1959, having been selected as one of NASA's Original Seven Mercury Astronauts. His second space flight on Gemini III earned him the distinction of being the first man to fly in space twice. His hard work, drive, persistence and skills as a top notch test pilot and engineer had landed him the title of commander for the first Apollo flight. Yet for Grissom, Apollo I was to be just the beginning. He had been told privately that if all went well, he would be the first American to walk on the moon. Although Grissom already had stacked up a very impressive list of career accomplishments, being first on the moon would be the ultimate achievement for the man who grew up in a small town during the lean years of the Great Depression. Grissom discovered that he was one of 110 military test pilots whose credentials had earned them an invitation to learn more about the space program in general and Project Mercury in particular. Gus liked the sound of the program but knew that competition for the final spots would be fierce. "I did not think my chances were very big when I saw some of the other men who were competing for the team. They were a good group, and I had a lot of respect for them. But I decided to give it the old school try and to take some of NASA's tests."13 Taking some of NASA's tests turned out to be more of an ordeal than Grissom could have imagined. He was sent to the Lovelace Clinic and Wright-Patterson AFB to receive extensive physical examinations and to submit to a battery of psychological tests. Grissom was nearly disqualified when doctors discovered that he suffered from hay fever. Without missing a beat, Grissom informed them that his allergies would not be a problem because "there won't be any ragweed pollen in space."14 Since no one could argue that point, they passed him on to the next series of tests.” Leroy Gordon Cooper “On April 9, 1959, NASA announced to the public their selections for the Project Mercury astronauts. Along with Cooper at the press conference in Washington, D.C. sat Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, John H. Glenn, Jr., M. Scott Carpenter, Walter M. Schirra, Jr. and Donald K. "Deke" Slayton. Once the selections and announcements had ended, the astronauts began their training program at Langley. This included a "little of everything" ranging from a graduate-level course in introductory space science to simulator training and scuba-diving. Training continued until the Langley Space Task Force was transferred to Houston, Texas.8 When each of the Mercury astronauts were assigned a different portion of the project and special assignments, to ensure pilot input, Cooper specialized in the Redstone rocket. The Redstone was already well-proven when it was first considered for use in Project Mercury. However, it had to be made compatible with the Mercury spacecraft and this took some close coordination and communication between several different agencies. Assigning an astronaut to help accomplish this paid off, for several reasons. To begin with, Cooper was a military man who had been assigned to a civilian agency, so he could understand the problems on both sides. As an engineer, he could talk the language of the other engineers. And, since he planned to ride the finished product himself, he could really become immersed in the problems.9 Like everyone else on the team, Cooper also had several development tasks in addition to his own regular astronaut training. One of these was the development of a personal survival knife which the astronauts wanted to carry in the capsule with them. They all knew from their experience as pilots that a knife is one of the most valuable tools for survival on both land and water, and they also knew that they would encounter a good deal of both of these elements during their flights. They would be orbiting over oceans and jungle and desert, and they wanted to be prepared for any emergency. Another task that Cooper was responsible for was to serve as chairman of an Emergency Egress Committee which was responsible for working out procedures for saving the astronaut in the event of an emergency on the pad.10 He served as capsule communicator (CAPCOM) for Mercury MA-6, John Glenn's first orbital flight in Friendship 7, and MA-7, Scott Carpenter's flight in Aurora 7. He also served as backup pilot for MA-8, Wally Schirra's mission in Sigma 7.11 Cooper's first flight began on May 15, 1963, when he was launched as the pilot of MA-9, the last Mercury mission. Cooper, in his Faith 7 capsule, orbited the Earth 22 times and logged more time in space than all five previous Mercury astronauts combined. His primary objectives were to evaluate the effects of a lengthier stay in space on man and to verify man as the primary spacecraft system. During the mission, he became the first American astronaut to sleep in orbit.12 His mission lasted 34 hours, 19 minutes and 49 seconds, during which he completed 22 orbits and traveled 546,167 miles at 17,547 miles per hour and pulled a maximum of 7.6G's. He achieved an altitude of 165.9 statute miles at apogee (highest point in orbit) and 100.3 statute miles at perigee (lowest point in orbit).13 ” Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • www.nasa.gov/ John Glenn: A Space Biography by Barbara Kramer http://www.boeing.com/history/mdc/mercury.htm Mercury 3 photo from http://search.store.yahoo.com/cgibin/nsearch?catalog=spaceimages&query=The+Mercury+Capsules&.autodone=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.space images.com%2Fnsearch.html T-38 photo from http://search.store.yahoo.com/cgibin/nsearch?catalog=spaceimages&query=The+Mercury+Capsules&.autodone=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.space images.com%2Fnsearch.html John Glenn (MA-6) leaves the crew quarters from http://search.store.yahoo.com/cgibin/nsearch?catalog=spaceimages&query=The+Mercury+Capsules&.autodone=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.space images.com%2Fnsearch.html The Mercury 7 astronauts from http://space.about.com/od/spaceexplorationhistory/ig/Project-MercuryOverview/Photo-of-Mercury-astronauts.htm All photos from slide 26 are from http://www.spaceimages.com/gemini.html Photo of Mission Control http://www.space.com/php/multimedia/imagedisplay/img_display.php?pic=ig_69.08_mercury_02.jpg&cap=All %20six%20Mercury%20missions%2C%20plus%20the%20first%20Project%20Gemini%20flight%2C%20were %20controlled%20from%20the%20Mercury%20Mission%20Control%20Center%20located%20at%20Cape% 20Canaveral.%20These%20consoles%20and%20viewing%20screens%20are%20now%20on%20display%2 0at%20the%20Kennedy%20Space%20Center%20Visitor%20Complex.%20Click%20to%20enlarge. Mercury Atlas 9 rocket and spacecraft on Launch Complex 14 at Cape Canaveral, FL in 1963 (slide #20). http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Mercury_Atlas_9.jpg/120px-Mercury_Atlas_9.jpg Monument at Pad 14 honoring Project Mercury (slide #19). Photo from http://space.about.com/od/spaceexplorationhistory/ig/Project-Mercury-Overview/Monument-at-Pad-14--Mercury-7.htm Bibliography (continued) • • • • Photo of John Glenn (slide 30) from http://www.spaceimages.com/mer06glen4.html Photo of “Little Joe” (slide #10) from http://www.astronautix.com/lvs/litlejoe.htm Diagram from http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Mercury_S pacecraft.png/775pxMercury_Spacecraft.png&imgrefurl=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Mercury_Spacecraft.png&h=60 0&w=775&sz=451&tbnid=diCe6R0IbBgJ:&tbnh=110&tbnw=142&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dmercury%2Bspacec raft&sa=X&oi=image_result&resnum=1&ct=image&cd=1 (slide #7) • http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://grin.hq.nasa.gov/IMAGES/SMALL/GPN-2000000651.jpg&imgrefurl=http://grin.hq.nasa.gov/BROWSE/mercury_astronaut_1.html&h=640&w=480&sz=439&t bnid=6dXMmXn15xgJ:&tbnh=137&tbnw=103&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dmercury%2Bastronaut%2Bpictures&s a=X&oi=image_result&resnum=1&ct=image&cd=2 • NASA's final Mercury-Atlas rocket stands poised for launch on Pad 14 in Cape Canaveral, Florida in May 1963. From http://www.space.com/php/multimedia/imagedisplay/img_display.php?pic=070203_last_mercury_02.jpg&cap= NASA%27s+final+MercuryAtlas+rocket+stands+poised+for+launch+on+Pad+14+in+Cape+Canaveral%2C+Florida+in+May+1963.+Cred it%3A+NASA.+Click+to+enlarge.+ • NASA logo from http://www.google.com/search?q=nasa+logo&sourceid=navclient-ff&ie=UTF8&rlz=1B3GGGL_enUS234US262 • Atlas booster in flight from http://www.spaceanimations.org/images/MercuryAtlas004.jpg • Shepard in Freedom 7 (prep. for launch) from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury-Redstone_3 • Launch of Alan Shepard http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury-Redstone_3 • Mercury capsule from http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Mercury_C apsule2.png/285pxMercury_Capsule2.png&imgrefurl=http://en.wikipedia.org/%3Ftitle%3DMercury_program&h=291&w=285&sz= 56&tbnid=A2_Ac5b_TDcJ:&tbnh=115&tbnw=113&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dmercury%2Bspacecraft&sa=X&oi=i mage_result&resnum=1&ct=image&cd=2 Bibliography (continued) http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/ 5b/Mercury_Capsule2.png/285pxMercury_Capsule2.png&imgrefurl=http://en.wikipedia.org/%3Ftitle%3DMercury_program&h=29 1&w=285&sz=56&tbnid=A2_Ac5b_TDcJ:&tbnh=115&tbnw=113&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dmercu ry%2Bspacecraft&sa=X&oi=image_result&resnum=1&ct=image&cd=2 Pictures of John Glenn from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Glenn Pictures of Walter Schirra from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wally_Schirra Pictures of Leroy Cooper from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_9 Pictures of Scott Carpenter from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott_Carpenter Pictures of Deke Slayton from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deke_Slayton Pictures of Virgil Grissom from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgil_Grissom Pictures of Alan Shepard from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Shepard Information of Shepard from http://history.nasa.gov/40thmerc7/shepard.htm Information of Schirra from http://history.nasa.gov/40thmerc7/schirra.htm Information of Grissom from http://history.nasa.gov/40themerc7/grissom.htm Information of Glenn from http://history.nasa.gov/40themerc7/glenn.htm Information of Cooper from http://history.nasa.gov/40themerc7/cooper.htm Information of Slayton from http://history.nasa.gov/40the merc7/slayton.htm Information of Carpenter from http://history.nasa.gov/40themerc7/carpenter.htm