The passthrough coefficient has fallen in developing countries.

advertisement

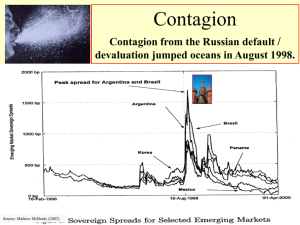

Contractionary Currency Crashes In Developing Countries Mundell-Fleming Lecture, Nov. 5, 2004; Fifth IMF Annual Research Conference. Forthcoming, IMF Staff Papers, 2005. IMF Institute, May 27, 2005. Jeffrey A. Frankel Harpel Professor KSG, Harvard University 1 Why are devaluations so costly? Political costs Economic costs If the answer is contractionary effects of devaluation, what is the mechanism? And what can a country do to minimize them? 2 After a devaluation, leaders lose their jobs… Twice as often within 1 yr. (30%) as in control group (14%) in 1960s. – R.Cooper, 1971. (Criterion is 10% deval.) Updated to 1970-2003, within 12 mo.s of devaluation (27%), vs, otherwise (21%) within 6 mo.s (19%), vs. as otherwise (12%). Difference is statistically significant at 0.5% level (Criterion is 25% deval, incl. 10% acceleration.) 3 Premier 2/3 more likely to lose his job within 6 mos. of currency crash 1970-2003 Change in premier No change in premier Total cases Within 6 mos. Of devaluation Other periods 36 812 (19.1%) (11.6%) 153 (81.0%) 6192 (88.4%) 189 7004 4 Fin.min.s / governors are even more likely to lose office in yr. Updated to Within 12 mos. Of devaluation 1971-2003 Change in fin.min. 14 or CB governor (58.3%) No change in fin.min. or CB gov. Total cases Other periods 212 (35.8%) 10 (41.7%) 380 (64.1%) 24 592 5 Political price of devaluations in developing countries Change in Premiership and Finance Minister or CB Governor* Comparison between Devaluation vs. Normal Times 70% 58.3% 60% 50% 35.8% 40% 29.3% 30% 20% 19.1% 20.5% 11.6% 10% 0% Premier 6-month (1971-2003) Premier 12-month (1971-2003) Normal period * IMF Governors IMF Governor 12-month (1995-1999) Post-devaluation period 6 Citations (1972-2003) Of Cooper (1971): 84 Of Mundell (1963): 319 Of Fleming (1962): 257 7 Possible reasons currency crashes correlate with change of leadership Elections cause devaluations, rather than the other way around (tho our timing is post-deval.) Devaluation as proxy for unpopular IMF austerity programs The government is perceived as having broken a promise High economic costs associated with devaluations. 8 Conditioning on IMF program does not affect leader turnover Dummy variable defined for initiation of IMF program within 3 months of currency crash does not raise frequency of leader job loss, relative to other devaluations. Thus conditioning on the IMF dummy variable has no discernible effect on frequency of leader job loss within 6 mo.s: 21.1% with an IMF program, vs. 21.9% without. Both similar to overall rate of job turnover following devaluations (22.8%) in full sample -still almost double the 11.6% rate in normal times. 9 Executives twice as likely to lose their jobs if the government had said “no devaluation.” Leader was changed within 12 mos unchanged Frequency within 12 mos of changes Of 6 promises 4 2 2/3 Of 15 with no prior promises 5 10 1/3 9 12 (whether by premier, fin min, or CB) not to devalue Total = 21 case studies 10 Executives > twice as likely lose their jobs if the government had said “no devaluation.” Leader was Changed within 6 mo.s Unchanged Frequency within 6 mo.s of changes Of 6 promises 3 3 .5 Of 15 with no prior promises 3 12 .2 6 15 (whether by premier, fin min, or CB) not to devalue Total = 21 case studies 11 Narrowing down source of political costs of devaluation As noted, IMF programs make no difference. Even in those cases where no assurances had been given over preceding month, rate of job loss (20%) still > no devaluation cases (11.6%) (or 33% at 12-month horizon > 20.5%) . Thus, although “broken promise” effect is there, political costs must also reflect economic pain. 12 Why did output fall sharply in many recent crises? Excessive expenditure-reduction (Sachs & Stiglitz)? Excessive fiscal contraction Excessive monetary contraction (high i => default) Versus what alternative? More expenditure-switching instead? Devaluations were very large as it was. Magical relaxation of external finance constraint? Who pays? Doesn’t change the graph But if devaluations are contractionary, internal balance line slopes the other way New intersection is hard to find May lose output regardless the policy mix. 13 Textbook model: right combination of i & E should attain new adverse external finance constraint, without recession 14 1990s version: External balance line slopes down, like internal balance line 15 Possible contractionary effects of devaluation Some require rapid passthrough, from exchange rate to prices of either: imported inputs consumer imports, & so W All TGs, & so the distribution of income CPI, & so M/CPI Other effects do not need passthrough Balance sheet effect 16 The passthrough coefficient has fallen in developing countries. Slow/incomplete passthrough of exchange rate changes has long been a property of US market & other large rich countries. After large devaluations in Asia and other emerging market countries from 1994 (Mexico) to 2001 (Argentina), most observers feared correspondingly large rises in local currency prices. It never happened. 17 Passthrough is greatest for prices of imports at dock, but less for retail and CPI Source: Frankel, Parsley & Wei (2004) – effect within one year passthrough coefficient Exchange Rate Passthrough to Domestic Prices 0.6 0.4 0.2 at the dock imported good prices local competitor prices consumer price index 18 Passthrough for less developed countries > for rich, historically. Source: Frankel, Parsley & Wei (2004) – effect within one year Passthrough and Income passthrough coefficient (Average 1990-2001) (Country Grouping Based on World Bank Classification) 0.7 0.6 12 countries 36 countries 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 28 countries 0.1 0 Low Income Middle Income High Income 19 Passthrough to prices of 8 narrow imported products Coefficient initially higher for developing countries (.8) than rich (.3), in 1990 Downward trend in coefficient during decade: Significant, regardless of income level Twice as fast for developing countries as for rich Partly explained, for rich, by rising real wages Speed of adjustment (ECM) Initially higher for developing countries than rich Significant downward trend for developing c.s (only) 20 exchange rate exporter's price ( s)*trend ( s) * log [RGDP per cap: (importer)/ exporter)] ( s)* tariff levels ( s)* log distance ( s)* log[RGDP: (importer)/ (exporter)] ( s)* log real wage ($) ( s)* l.t. inflation ( s)* l.t. exchange rate variability ( s)* US Importer dummy ECM terms omitted Equation 1 Rich Dev. 0.133*** 0.365*** (0.031) (0.045) 0.108 *** -0.052 (0.025) (0.042) Equation2 Rich Dev. 0.310 *** 0.496 *** (0.075) (0.101) 0.108 *** -0.023 (0.025) (0.042) Equation 8 Rich Dev. 2.489 ** -1.607 (1.144) (1.595) 0.082*** -0.069 (0.028) (0.062) -0.025 *** (0.009) -0.014 (0.012) -0.022 (0.034) -0.046 ** (0.019) -0.050 (0.048) -0.431 (0.265) -0.029 (0.048) 0.016 (0.030) 0.368 (0.314) 0.049 (0.091) 0.029 (0.044) -0.019 * (0.010) 2.135 (1.871) -2.262 (4.932) -0.442** (0.190) 0.017 (0.013) -1.781 (1.884) 0.890 (5.112) -0.026 ** (0.013) 21 Passthrough coefficient fell substantially in the 1990s. For developing countries, out of total sample of 76 Passthrough coefficient start of sample (1990) Overall trend sample For import prices of 8 narrowly defined goods .81 .50 -.05/ yr. For CPI .68 .33 -.05/ yr. Estimates from Frankel, Parsley & Wei, NBER WP no. 11199 (2005), “Slow Passthrough Around the World: A Recent Import to Developing Countries?” 22 Balance sheet effect is most important of the contractionary devaluation effects Analytical literature on balance sheet effect includes: Kiyotaki & Moore (1997), Krugman (1999), Aghion, Banerjee & Bacchetta (2000), Cespedes, Chang & Velasco (2000, 2003), Chang & Velasco (1999), Caballero and Krishnamurty (2002), Christiano, Gust & Roldos (2002), Dornbusch (2001), Mendoza (2002), Calvo, Izquierdo, & Talvi (2003), Cavallo (2004), Eichengreen & Hausmann (1999) and many others. Empirical evidence of its output cost includes: Cavallo, Kisselev, Perri and Roubini (2002) Guidotti, Sturzenneger and Villar (2003) 23 Foreign-denominated debt in crises x real devaluation => Output loss Source: M.Cavallo, K.Kisselev, F.Perri, & N.Roubini, 2002. Some suggested influences on the balance sheet effect Eichengreen & Hausmann (1999) made the structural inability to borrow in local currencies famous under the name “original sin.” Is it historical fate? Some argue that the culprit is adjustable pegs. Short run: During the procrastination phase, composition of debt typically shifts to $. Medium run: Trade openness affects vulnerability to currency crashes. 25 Procrastination phase ≡ period after reserves peak, but before the speculative attack Typically lasts 6-13 mo.s – Frankel & Wei (WB, 2005) E.g., Mexico, 1994 Four ways to “gamble for resurrection” Officials announce won’t devalue Run down reserves Shift composition of debt to short-term Shift composition to $-denominated Each ploy may gain time, but raises cost if devaluation comes. 26 Exhaustion of Mexico’s Reserves Up to December 1994 Crisis Data source: IMF International Financial Statistics. 35 0 0 0. 00 30 0 0 0. 00 25 0 0 0. 00 20 0 0 0. 00 IMF PROGRAM 15 0 0 0. 00 CRISIS 10 0 0 0. 00 5 0 0 0. 00 L eve l 1995M4 1995M3 1995M2 1995M1 1994M12 1994M11 1994M10 1994M9 1994M8 1994M7 1994M6 1994M5 1994M4 1994M3 1994M2 1994M1 1993M12 1993M11 1993M10 1993M9 1993M8 1993M7 1993M6 1993M5 1993M4 1993M3 1993M2 1993M1 1992M12 0. 00 3m Mo ving A vg 27 Mexico’s shift to $-linked debt, in 1992-94 Data source: Mexican Ministry of Finance and Public Credit. Evolution of Mexican debt according to currency denomination 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% tesobonos/(tesobonos+cetes) Nov-95 Sep-95 Jul-95 May-95 Mar-95 Jan-95 Nov-94 Sep-94 Jul-94 May-94 Mar-94 Jan-94 Nov-93 Sep-93 Jul-93 May-93 Mar-93 Jan-93 Nov-92 Sep-92 Jul-92 May-92 Mar-92 Jan-92 0% tesobonos/total domestic debt 28 Mexico’s shift to short-term debt in 1992-94 Data source: Mexican Ministry of Finance and Public Credit. Evolution of Mexican debt according to maturity % long term/(long term+short term) - left axis Nov-95 Sep-95 Jul-95 May-95 Mar-95 Jan-95 Nov-94 Sep-94 Jul-94 May-94 Mar-94 Jan-94 Nov-93 0 Sep-93 90% Jul-93 100 May-93 92% Mar-93 200 Jan-93 94% Nov-92 300 Sep-92 96% Jul-92 400 May-92 98% Mar-92 500 Jan-92 100% average maturity in days - right axis 29 Lesson After inflows cease, adjust to new external balance early while it is still possible to maintain internal balance; Rather than procrastinating by running down reserves & shifting to s.t. $ debt. Because after the crash, any combination of high i & devaluation may be contractionary. 30 In long run, how does openness to trade affect a country’s vulnerability? Some say openness raises vulnerability to sudden stops Vulnerability to real shocks, financial shocks; loss of trade credit Empirical support: Milesi-Ferretti & Razin (1998, 2000) Others say it reduces vulnerability Sachs (1985): explains Asian resilience, vs. Latin America Trade is a hostage that reassures creditors Eaton & Gersovitz (1981), Rose (2002) If m is lower, cost of adjustment to given cut-off is higher measured by necessary expenditure-reduction at given prices or by necessary devaluation (with corresponding contractionary effects) Argentina is favorite example of toxic interaction of low trade/GDP and balance sheet effect Guidotti, Sturzenegger & Villar, (2003), Calvo & Talvi (2004), Desai & Mitra (2004), Cavallo (2004), and Secy. Paul O’Neill. Empirical support: Calvo, Izquierdo & Mejia (2003); Edwards (2004a,b) 31 Countries of currency crashes tend to be less open to trade, especially those with sudden stops as well Average Opennes and Fitted Opennes by category of Crisis 0.14 0.65 0.64 0.12 0.63 0.62 0.61 0.08 0.6 0.06 Openness Fitted Openness 0.1 Fitted Open Open 0.59 0.58 0.04 0.57 0.02 0.56 0 0.55 No crash, no SS (1815 events) Crash but no SS (317 events) Crash and SS (18 events) 32 Countries that are less open to trade are more prone to sudden stops & currency crashes Sudden Stops (SS1) and Currency Crises (Crash) by level of openness 350 292 300 Number of Episodes 250 200 > Mean open < Mean open 150 127 100 52 50 34 0 SS1 (86 events) Crashes (419 events) 33 Endogeneity of trade/GDP Possible channels of endogeneity of openness Via income: richer countries tend to liberalize Part of a more general reform strategy driven by proglobalization philosophy or “Washington Consensus” forces. Experience with crises -- the dependent variable -- may itself cause liberalization, via an IMF program. Feedbacks betw. trade & financial openness. Aizenman (2003) Solution: Use gravity as IV for trade: “Does Openness to Trade Make Countries More Vulnerable to Sudden Stops, Or Less? Using Gravity to Establish Causality” – Cavallo & Frankel (2004) 34 Predicting sudden stops, while treating endogeneity of trade Source: Cavallo & Frankel (2004) Trade openness Foreign Debt/GDP t-1 Liability Dollarization CA/GDP observations t-1 t-1 Ordinary probit IV (gravity) -0.53 (0.259)** -0.080 (0.217) (0.316 (0.195) -2.45 (0.813)** 0.196 (0.275) 0.591 (0.256)*** -4.068 (1.297)** -7.386 (2.06)*** 778 1062 35 Predicting currency crashes, while treating endogeneity of trade Source: Cavallo & Frankel (2004) Ordinary probit Trade openness Foreign Debt/GDP t-1 Liability Dollarizationt-1 observations -0.37 (0.21)* 0.35 (0.18)** 0.04 (0.20) IV (gravity) -0.97 (0.59)* 0.57 (0.23)** -0.11 (0.18) 798 1196 36 S Stops & crashes rise also when it is gravity-fitted openness that is low Sudden Stops (SS1) and Currency Crashes (Crash) by level of fitted openness 350 313 300 250 200 > Mean fitted open < Mean fitted open 150 106 100 67 50 19 0 SS1 (86 events) Crashes (419 events) Number of Episodes 37 Conclusion An increase in trade openness of 10 percentage points decreases likelihood of a sudden stop (definition of Calvo, et al.) by approximately 32%. E.g., moving from Argentina’s trade share (.2) to Australia’s (.3) CA/GDP is the other strongest predictor Increase in openness also decreases the likelihood of currency crash, defined as 25% increase in exchange market pressure≡ (exchange rate * reserves) Foreign debt/GDP or Reserves/imports become the other strong predictors Also some evidence that openness reduces the output cost associated with crises 38 “Take-aways” Leaders are twice as likely to lose office after a devaluation. Passthrough has declined sharply. To minimize contractionary effects of devaluation, countries should avoid weakening of their balance sheets during “procrastination phase” of debt cycle; in the long term, open to trade. 39 The highway analogy Superhighways are useful, get you where you want to go quicker. But accidents at high speeds are more likely fatal. -- Merton Sudden stops: “It’s not the speed that kills, it’s the sudden stops” – Dornbusch sharp disappearance of private capital inflows, reflected (esp. at 1st) in reserve declines, & (soon) in disappearance of previously large CA deficit - Calvo Superhighways: Modern financial markets get you where you want to go fast, but accidents are bigger, and so more care is required. -- Merton Is it the road or the driver? Even when multiple countries have accidents in the same stretch of road, their own policies are also important determinants; it’s not just the fault of the system. – Summers Contagion is also a contributor to multi-car accidents.40 Highway analogy, continued Moral hazard -- G7/IMF bailouts reduce impact of given crisis in the LR undermine the incentive for investors & borrowers to be careful. Like air bags and ambulances. But to claim that moral hazard means we should abolish the IMF would be like claiming that drivers would be safer with a spike in the center of the steering wheel column – Mussa. Optimal sequence: Highway off-ramp should not dump highspeed traffic into center of a village before streets are paved, intersections regulated, & pedestrians learn to walk on sidewalks. So a country with a primitive domestic financial system perhaps should not open to the full force of international capital flows before domestic reforms & prudential regulation. Slowing down: There may be a role for controls on capital inflow (speed bumps & posted limits). Reaction time: How driver reacts in short interval between appearance of hazard and moment of impact (speculative attack) influences outcome. Adjust, rather than procrastinate by using up reserves & switching to short-term $ debt – JF Routine defensive driving: Keeping high reserves and an economy open to trade is like leaving ample following-distance. 41