Security Kritik - CNDI - 2011

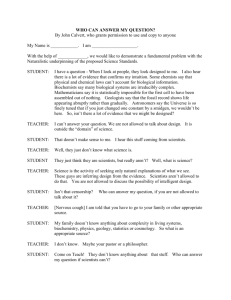

advertisement