Turkish Folk Tales

advertisement

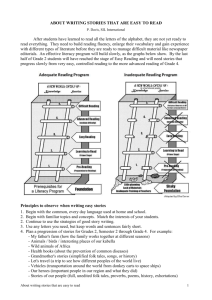

European Tales in Children Words Resource TURKISH FOLK TALES by Ayça Oğuz Hasan Kağnıcı İlköğretim Okulu İstanbul / Turkey CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 3 TURKISH FOLK TALES .................................................................................................................................... 5 DEDE KORKUT ................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOME TALES FROM THE BOOK OF DEDE KORKUT: .............................................................................................. 6 LEGEND I : THE STORY OF BOGHACH KHAN, SON OF DIRSE KHAN ......................................................... 6 LEGEND II: THE SALUR KAZAN’S HAUSE ............................................................................................. 6 LEGEND III: THE STORY OF BAMSI BEYREK OF THE GREY HORSE ............................................................ 7 MEVLANA ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 SOME TALES WRITTEN BY MEVLANA; .............................................................................................................. 11 THE ELEPHANT IN THE DARK , ON THE RECONCILIATION OF CONTRARIETIES ............................................. 11 THE MOUSE AND THE CAMEL, A WARNING AGAINST SPIRITUAL PRIDE ..................................................... 11 THE GRAMMARIAN AND THE BOATMAN ............................................................................................... 12 NASRETTIN HOCA .......................................................................................................................................... 13 SOME OF HOCA'S STORIES ......................................................................................................................... 14 HOW TO USE A DONKEY … .................................................................................................................. 14 THE SLAP ......................................................................................................................................... 15 EAT, MY COAT, EAT.......................................................................................................................... 15 THE CAULDRON THAT DİED ............................................................................................................... 15 KARAGÖZ & HACİVAT .................................................................................................................................. 17 SOME REPRESENTATIVE KARAGÖZ SCENARIOS ................................................................................. 18 THE PLEASURE TRIP TO YALOVA: .......................................................................................................... 18 THE PUBLIC SCRIBE: ........................................................................................................................... 18 KARAGÖZ IN THE POETRY CONTEST: ...................................................................................................... 19 THE SWING: ...................................................................................................................................... 19 THE PUBLIC BATH: ............................................................................................................................. 19 THE PURSE OR KARAGÖZ, THE WRESTLER: ............................................................................................. 19 THE GARDEN:.................................................................................................................................... 19 TAHIR AND ZÜHRE:............................................................................................................................. 19 KELOĞLAN ....................................................................................................................................................... 20 SOME OF THE KELOĞLAN STORIES.. .................................................................................................................. 21 KELOĞLAN AND MAGICAL BOWL................................................................................................... 21 KELOĞLAN AND HIS SQUIRREL FRIEND .......................................................................................... 21 KELOĞLAN AND GIANT .................................................................................................................. 22 SOURCES ............................................................................................................................................................ 24 Introduction “Once there was - once there wasn't, before the time in the past, the sieve was in the chaff, while the camels were barbers as the fleas were porters, while I was “ tıngır mıngır” rocking my father's cradle...” Many traditional Turkish tales are, introduced with this formulaic jingle with many variants. In these lilting overtures, one finds the spirit and some of the essential features of the story: The vivid imagination, irreconcilable paradoxes with built-in syllabic meters and internal rhymes, a comic sense bordering on the absurd, a sense of the mutability of the world, the aesthetic urge to avoid loquaciousness, the continuing presence of the past, and the predilection of the narrative to maintain freedom from time and place. The traces of Turkish Folk Tale tradition can be traced back to the dawn of Turkish history in Central Asia more than fifteen centuries ago.1 The synthesis encompassed the enormous inheritance of the Turks and the rich material they amassed from the Asian tradition, from the Islamic lore, from the Middle East, Byzantium, the Balkans, and the rest of Europe.2 Seljuk Anatolia and the Ottoman Empire nurtured storytelling as a prevalent form of entertainment and enlightenment: Professional storytellers, preachers and teachers and comedians kept the tradition alive, developed new versions, and contributed fresh material. Mothers not only sang lullabies, but they also recounted familiar and unfamiliar bedtime stories.3 In daily conversations were peppered with anecdotes, funny or instructive which shows Turkish repertoire is so vast and the diversity of tales so encompassing. Some Turkish tales are sufficiently historical to qualify as legends. Others are utterly fanciful, however seriously they may be taken by tellers and listeners.4 Most of them have leaps of the imagination into the realm of phantasmagoria. Even in realistic and moralistic stories, there is usually an element of whimsy. Bizarre transformations abound. There are abrupt turns of events, inexplicable changes of identity. In the early Turkish Folk Tales’ mostly depends on paramount-poetry, music, dance, and the oral narrative. In later centuries, with the Turks migrating into Asia Minor and then holding sway in far-flung territories, a great synthesis of oral literature evolved. The synthesis comprised the autochthonous legacy of the Turks and the rich material they amassed from the Asian tradition, from the Islamic lore, from the Middle East, Byzantium, the Balkans, and the rest of Europe. That is why the Turkish repertoire is so vast and the diversity of tales so encompassing. Their shamans had, from the outset relied on mesmerizing verses and instructive tales in shaping the spiritual life of the tribes. Tales were then talismans and thaumaturgical potions. During the process of conversion to Islam, missionaries and proselytizers used the legends and the historical accounts of the new faith to good advantage. Tales became tantalizing evangelical tools. Seljuk Anatolia and the Ottoman Empire nurtured storytelling as a prevalent form of entertainment and enlightenment: Professional storytellers, preachers and teachers and comedians kept the 1 2 3 4 Talat Sait Halman , Ministry of Culture , Republic of Turkey Gazi Univ., Basic Characteristic Of Turkish Folk Tales, Turkiye FTT, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hearth of the Turkish Tales, Republic of Turkey Walker S., Warren, The Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative, Turkish Oral Tradition in Texas: Oral Tradition 7/1 (1991) tradition alive, developed new versions, and contributed fresh material. Mothers not only sang lullabies but they also recounted familiar and unfamiliar bed time stories. Everyday conversation was peppered with anecdotes, funny or instructive, religious or profane. Repetitions are also common within the structure of the tales. The description of beauties, different characters and so forth are all described with repetitive phrases. Even the description of actions and the passing of time are expressed with such expressions. Thus, it is not a coincidence that a Turkish Folk Tale may well contain a great number of idioms, proverbs, tongue twister and even prayers. Turkish Folk Tales are mostly about love and heroism and sometimes these two themes are brought together in a single tale.5 The events in Folk Tales are generally realistic as a mirror of the period and the social background in which they are created to a great extend. However, the heroes/heroines are equipped with some supernatural qualifications, which gives the tale a mystic dimension; The hero/heroine is generally an only child and his/her birth has an extraordinary aspect which pervades his/her whole life. The main character may be an ordinary person as well as being a noble one. It is very common that girls are from rich families and of royal families while the boys are common people of poor families. As a touch of fairy tales, the hero/heroine of the folk tale, may also communicate with animals and inanimate objects As for epics and fairy tales, there are special narrators for folk tales, as well. Fairy tale narrators are supposed to be females but it generally requires a man to narrate a folk tale. It does not mean that a female cannot narrate a folk tale, but it is not very common.6 Horses are also important in Turkish Folk Tales. Just like the heroes, they are often given supernatural qualifications. Turkish Tales are frequently ending with these lyric; “They have had their wish fulfilled, Let’s go to their bedstead” 5 Gunay, Umay, Hacettepe Univ, “APPLlCATION OF PROPP'S MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS TO TURKISH FOLK TALES,” Edebiyat dergisi, 6 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hearth of the Turkish Tales, Republic of Turkey Turkish Folk Tales As in other cultures, Turkish Folk Tales, as a step between epic and novels, are the fruit of oral tradition and even today there are still some folk tales which have not been written down, yet. Historically, Turkish Folk Tales appear following the heroic epic tradition as one of the early fruit of settled life after the nomadic life style. They take their roots from legends and fairy tales as well as carrying some characteristics of epics as a genre. Although the genres that constitute the oral Turkish literature differ in form and theme, Turkish folk tales embody texts and characteristics of such various genres. However, there are still some basic characteristics that differ the Folk Tales from other oral literary genres. Dede Korkut Dede Korkut is a Central Asia legend, the principal repository of ethnic identity, history, customs and the value systems of its owners and composers which were passing from generation to generation in an oral form and written first at the sixteenth century.. It commemorates struggles for freedom at a time when the Oghuz were a herding people who lived in tents.7 The Book of Dede Korkut, also spelled as Dada Gorgud, Dede Qorqut or Korkut-ata (Turkish: Dede Korkut Kitabı, Azerbaijani: Kitabi Dədə Qorqud, Russian: Китаби деде Коркуд, Turkmen: Gorkut-ata), is the most famous epic story of the Oghuz Turks (also known as Turkmens or Turcomans). it is the principal repository of ethnic identity, history, customs and the value systems of the Turkish peoples throughout history.8 Now it is known that the term 'Oghuz' was gradually supplanted among the Turks themselves as Turkmen, 'Turcoman',9 from the mid tenth century on, a process which was completed by the beginning of the thirteenth century. The stories were written in prose, but peppered with poetic passages. The Turkmen variant of the Book of Dede Korkut contains sixteen stories. The twelve stories that comprise the bulk of the work were written down after the Turks converted to Islam, and the heroes are often portrayed as good Muslims while the villains are referred to as infidels, but there are also many references to magic and shamanism. The character Dede Korkut is a widely-renowned soothsayer and bard, and serves to link the stories together, and the thirteenth chapter of the book compiles sayings attributed to him. He is a splendid figure in the epic adventure. He has the power to see the future and give news from the future. Dede Korkut was the first teller of the legends. In the dastans, the advisor or 7 Kafadar, C. “in Between Two Worlds: Construction of the Ottoman states”, University of California Press,1995. Great Soviet Encyclopedia, “Dastan” Third edition, Moscow, 1970 9 Lewis, G. The Book of Dede Korkut. Penguin Books, 1974, 8 sage, solving the difficulties faced by tribal members. He has lived for 295 years and he has been a vizier of The Great Khan of the Oghuz Turks. He has a special instrument and he plays it to say important words. The tales tell of warriors and battles and are likely grounded in the conflicts between the Oghuz and the Pechenegs and Kipchaks. In 2000, "Kitab-i Dede Qorqud" was awarded the UNESCO literary work of the year as a celebration of its 1300th Anniversary. 10 Some tales from The Book of Dede Korkut: LEGEND I : THE STORY OF BOGHACH KHAN, SON OF DIRSE KHAN Dirse Khan is upset when Bayindir Khan, leader of the Oghuz Turks, relegates him to a black tent. He is informed that the order is that men with sons are entitled to a white tent, men with only daughters to a red tent, and men with no offspring to a black one. Dirse Khan exchanges poetry with his wife about their desire to alter their childless state. He offers sacrifice of stallions, rams and he-camels. When Dirse Khan's son is fifteen, he's playing knuckle bones and Bayindir Khan's prize bull attacks him. His fellow gamers flee, but the son of Dirse Khan stands his ground. The boy gave the bull a merciless punch on the forehead and the bull went sliding on his rump. Again he came and charged the boy. Again the boy gave him a mighty punch on the forehead, but this time he kept his fist pressed against the bull's forehead and shoved him to the end of the arena. They struggle for a while, until at last the boy decapitates the bull, obtaining thus his name, Boghach, Bull-man. He's richly rewarded, but his father's forty warriors are jealous and resentful. They tell tales to Dirse Khan, falsely saying Boghach plans to commit patricide. Dirse Khan strikes first. As the boy lies there bleeding, the crows and ravens being kept at bay by Boghach Khan's two dogs, his mother comes upon him. They exchange poetic concern about his wound and assurance that he'll recover. He does and the villains seize his father. He rides with his men to the rescue. He led his forty men, he charged, he faught and gave battle. Some he beheaded, some he took prisoner, and he freed his father. The Book of Dede Korkut: LEGEND II: THE SALUR KAZAN’S HAUSE Salur Kazan is having a great drinking party and decides to go hunting. While he's away, raiders strike, carrying off all his goods, as well as all the people there, including Kazan's wife. They decide to seize also Kazan's sheep, but these are guarded by three brothers, including one worthy of an Irish saga. When the raiders arrive with their loot and captives, demanding the sheep and offering the shepherd a princedom, if he hands them over, the 10 UNESCO website, accessed March 19, 2007 Celebration of anniversaries with which UNESCO was associated since 1996, UNESCO website, accessed March 19, 2007 shepherd responds with satirical verse and his sling. When he shot his first shot he toppled two or three of them; when he shot his second he toppled three or four of them. Terror filled the infidel's eyes. Karajuk the shepherd with his sling- stones laid three hundred of the infidel low. Despite putting the foe to flight with three hundred dead, Karajuk finds his master ungrateful. Why are you angry with me, Lord Kazan? Is there no faith in your heart? Six hundred unbelievers attacked me too, my two brothers were killed, I killed three hundred unbelievers, I faught the good fight, I did not let the unbelievers have the fat sheep and the thin yearlings from your gate. I was wounded in three places, my dark head was stunned, I was all alone; is this what you're blaming me for The shepherd feeds Lord Kazan and offers to go and retrieve Kazan's goods and people or die trying. Kazan, feeling shame at the thought of being accompanied by a mere shepherd, ties the guy to a tree. Karajuk simply pulls the tree out of the ground and runs, carrying the tree with him, after Kazan. Kazan unties him and they proceed together. While Prince Shokli is trying to learn which of the forty-one women he's captured is Kazan's wife so he can take her as a concubine, Kazan and Karajuk arrive. There comes here a description of Karajuk's sling: The leather of Karajuk's sling was made of the skins of three year old calves, the thongs were of the skins of three goats, and one goat skin made the tassel. At every shot it threw a hundredweight of stone. The stone it fired would not fall to earth; if ever it did fall it would shatter into dust, it would explode like a furnace, and for three years no grass would grow where the stone fell. Verse, boasting and satirical, is exchanged and then there's a listing of Oghuz notables who arrive to take part in the fun. On that day there was a battle like doomsday and the field was full of heads. Heads were cut off like balls. Falcon-swift horses galloped until they lost their shoes, pure black steel swords were wielded until they lost their edges, the three-feathered, beech-wood arrows were shot until they lost their points. There's a great victory celebration. Dede Korkut comes and tells tales. Blessings are called upon the royal listener. The Book of Dede Korkut: LEGEND III: THE STORY OF BAMSI BEYREK OF THE GREY HORSE Bamsi Beyrek was born in response to the prayer of his hitherto sonless father. The now delighted father summons merchants and bids them obtain splendid gifts for the newborn. They travel to the Byzantine metropolis of Constantinople. For Prince Bure's son they bought a grey horse, sea-born; a strong bow too they bought, with a white grip, and a six-ridged mace. The trip took a while. After sixteen years, as they are nearing Turkish territory, five hundred bandids attack them. One escapes to tell his tale to a warrior who at once mounts his steed and rides to the rescue. The appreciative merchants say he can take whatever he wants from his goods. What catches his eye are the three gifts for the son of Prince Bay Bure. When informed of this, he says then he'll wait till they give these gifts to him in the presence of his father. Now, when Beyrek's father had prayed for a son, another had prayed for a daughter to marry that son. Beyrek encounters this maiden while hunting deer. The boy and the girl have great fun racing their horses, having an archery contest and then a wrestling match, and Beyrek decides this is the one he wants to marry. Dede Korkut acts as intermediary. The maiden's brother, Crazy Karchar, wants a dowry of a thousand camels, a thousand horses, a thousand rams, a thousand dogs and, "a thousand huge fleas" . He gets his wish and Dede Korkut even helps him with his infestation of fleas by telling him to jump in the river. However, Beyrek has barely donned his bridegroom's crimson caftan, when seven hundred raiding Abkhazians attack and carry him off. After they've held him for sixteen years, despicable Yaltajuk, son of Yalanji, violating traditional Turkish truthfulness, says Beyrek is dead, and even shows the bride one of the groom's shirts which Yaltajuk dipped in blood. The news of her new betrothal to Yaltajuk reaches Beyrek. He becomes sad, something noticed by the Abkhazian princess. 'Why are you downcast, my kingly warrior? Whenever I have come I have seen you cheerful, smiling and dancing. What has happened now.' He tells her, and she offers to help him escape, if he agrees to return and marry her. He replies: May I be sliced on my own sword, may I be spitted on my own arrow, may I be slashed like the ground, may I blow in dust like the earth, if I reach the Oghuz land safely and do not come back and marry you. He first encounters his grey sea-born horse which gladly greets him. He recites a poem to it, calling it, "better than any brother" and meeting a bard, borrows the bard's lute, handing over his horse as surety. Then, disguised as a bard, he meets his sister and other wedding guests. Using his own strong bow, he wins an archery contest against despicable Yaltajuk. He then reveals himself to the bride. The joyful news spreads and Beyrek marries the Abkhazian princess. Mevlana “Come, Come again ! Whatever you are... Whether you are infidel, idolater or fireworshipper. Whether you have broken your penitence a hundred times Ours is the portal of hope, come as you are.” “Mevlana's name is Mohammad Jelaleddin and his titles are Lord (Hudavendigar), Mevlana, Mystery of God Almighty (Sirru'llahu'a'zam), Mevlevi and Rumi. The word Rumi means an Anatolian.” 11 Mevlana was born in the city of Balkh in Afghanistan and he lived most of his life in Konya , seat of the Selçuk Empire, located in present day Turkey. Mevlana Celalettin Rumi, was a philosopher and his doctrine advocates unlimited tolerance, positive reasoning, goodness, charity and awareness through love. To him and to his disciples all religions are more or less truth. Looking with the same eye all of the religions, his peaceful and tolerant teaching has appealed to men of all sects and creeds. His father was a theologian and mystic, and after his death Rumi took over the role of sheikh in Konya's dervish community. After meeting a wandering dervish, Shams of Tabriz, Mevlana Celalettin Rumi became enveloped in a world of mystical conversation. Sham became one of the most profound influences in his life. Mevlana also was educated in the two major university centers of the time, Aleppo and Damascus; he was a well rounded scholar who had accumulated much theological and scientific knowledge. He had such command of Turkish, Persian, Arabic, Greek that he could write poetry in all four languages. He also had good relations with Haci Bektas Veli of the Bektashi Order and his dervishes. 11 Dr. Hidayetoglu A. Selâhaddin, “Hazret-i Mevlana”, University Of Selçuk, Faculty of Theolog, Turkish-Islamic Literature Deparment Mevlana wrote all his works about love, the basis and essence of life. The reason for the creation of the universe is love. n approaching issues pertaining to daily life he is a rationalist, but in approaching spiritual and mystical matters he recognizes only the mastery of the heart and emotions. According to him, the only way to approach absolute being is through love; and God's love is everywhere, permeating everything. Love of God, which is the highest points of life, is the most precious thing. Starting from the point , Mevlana renounced this divine love in thousands of verses. It is possible to classify his thoughts on love under four hedings: comparison between intellect and love ascendancy and value of love which is for mortal beings; and finally, the pitiable situation of those who have not a share in love. Mevlana, who found out that the essence of creation and man's exaltation of his worldly body was in love alone, never considered a loveless life as a real life: "Luck becomes your sweetheart , if it becomes helpful. Love helps you in your daily routines , Consider not the loveless life as life. For , it will be out of consideration."12 Hence, Mevlana considered love as a state of whih every sufi must have experience. He is of the opinion that the heart that is drowned in God , the Beloved One, with love is precious and preferable. 13 This vision impelled Mevlana to transcend all differences and prejudices, and formed the basis of his immense tolerance and of his real and deep humanism. With these characteristics, Mevlana and his thought transcended the boundaries of his time and thus he and his writings are still relevant and fresh in this day and age, some 700 years after. In sufi thought, intellect and science are incompetent in comprehending metaphysical realities. They may lead a man to a certain point, but not to the target. However, if a man has wings of love , he becomes lofty in a way that he can never imagine. As a matter of fact , the nature of this love cannot be explained by words and squeezed between lines. Whilst the pen was making haste in writing , it split upon itself as soon as it came to Love. Mevlana stated in Mesnevi that he whose garment was rent by a mighty love was purged of covetousness and all defect: and love was the physician of all our is and the remedy of our pide and vainglory; an also the earthly body soared the skies through love. By so saying , he clearly indicates that man was cleared off pride, worldly desire , envy, grudge, and many other eil habits through Divine Love only. If those who knew the spiritual world were in the majority in a society, all worldly worries and defects would be removed . On the other hand , Mevlana advisd that just as a man learned a trade to earn a livelihood for 12 13 (Mecalis-i Sab'a,43) (Mesnevi,I/1853). the body , we should learn trade to ear the Hereafter, that is , God's forgiveness, again, the earnings of religion were love.14 Near the end of his life, Rumi focused on his greatest achievement, Masnavi. After twelve years of work on this masterpiece, Mevlana Celalettin Rumi died in 1273. Some Tales written by Mevlana; THE ELEPHANT IN THE DARK , ON THE RECONCILIATION OF CONTRARIETIES SOME Hindus had brought an elephant for exhibition and placed it in a dark house. Crowds of people were going into that dark place to see the beat. Finding that ocular inspection was impossible, each visitor felt it with his palm in the darkness. The palm of one fell on the trunk. ‘This creature is like a water-spout,’ he said. The hand of another lighted on the elephant’s ear. To him the beat was evidently like a fan. Another rubbed against its leg. ‘I found the elephant’s shape is like a pillar,’ he said. Another laid his hand on its back. ‘Certainly this elephant was like a throne,’ he said. The sensual eye is just like the palm of the hand. The palm has not the means of covering the whole of the best. The eye of the Sea is one thing and the foam another. Let the foam go, and gaze with the eye of the Sea. Day and night foam-flecks are flung from the sea: of amazing! You behold the foam but not the Sea. We are like boats dashing together; our eyes are darkened, yet we are in clear water. THE MOUSE AND THE CAMEL , A WARNING AGAINST SPIRITUAL PRIDE A little mouse once caught in its paws a camel's head-rope and in a spirit of emulation went off with it. Because of the nimbleness with which the camel set off along with him the mouse was duped into thinking himself a champion. The flash of his thought struck the camel. 'Go on, enjoy yourself,' he grunted. 'I have something to teach you, presently!' 14 (Mesnevi, II/2592-2603) Presently the mouse came to the margin of a great river, such as would have cast down any lion or wolf. There the mouse halted, struck all of a heap. 'Comrade over mountain and plain,' said the camel, 'why this standing still? Why are you dismayed? Step on like a man! Into the river with you! You are my guide and leader; do not stop here!' 'But this a vast and deep river,' said the mouse. 'I am afraid of being drowned, comrade.' 'Let me see how deep the water is,' said the camel, and quickly set foot in it. The water only comes up to my knee,' he went on, 'Blind mouse, why were you dismayed? Why did you lose your head?' 'To you it is an ant, but to me it is a dragon,' said the mouse. 'There are great differences between one knee and another. If it only reaches your knee, clever camel, it passes a hundred cubits over my head.' 'Be not so arrogant another time,' said the camel, 'lest you are consumed body and soul by the sparks of my wrath. Emulate mice like yourself; a mouse has no business to hobnob with camels.' 'I repent,' said the mouse. 'For God's sake get me across this deadly water!' 'Listen,' said the camel, taking compassion on the mouse. 'Jump up and sit on my hump. This passage has been entrusted to me; I would take across hundreds of thousands like you.' THE GRAMMARIAN AND THE BOATMAN A grammarian once embarked in a boat. Turning to the boatman with a self-satisfied air he asked him: ‘Have you ever studied grammar?’ ‘No,’ replied the boatman. “I am just a simple boatman” ‘Then half your life has gone to waste,’ the grammarian replied. The boatman thereupon felt very depressed, disturbed in his heart from burning sorrow, but kept silent from answering at that moment. Presently the wind tossed the boat into a whirlpool. The boatman shouted to the grammarian: ‘Do you know how to swim?’ ‘No’ the grammarian replied, ‘my well-spoken, handsome fellow’. ‘In that case, grammarian,’ the boatman remarked, ‘the whole of your life has gone to waste, for the boat is going to drown in these whirlpools.’ Nasrettin Hoca Nasrettin Hoca is Turkey's (and perhaps all of Islam's) best-known trickster. His legendary wit and droll trickery were possibly based on the exploits and words of a historical imam. “He was born in 1208 in Hortu village near town Sivrihisar (near Afyon in Turkey) in the west part of Central Anatolia. He moved in 1237 to Akşehir town to study under notably scholars of the time as Seyid Mahmud Hayrani and Seyid Haci Ibrahim. He served as Kadi, Muslim judge, from time to time till 1284 which is the date of his death.”15 Nasrettin's name is also commonly spelled Nasrudeen, Nasruddin, Nasr ud-Din, Nasredin, Naseeruddin, Nasruddin, Nasr Eddin, Nastradhin, Nasreddine, Nastratin, Nusrettin, Nasrettin, Nostradin and Nastradin. His name is sometime preceded or followed by a title of wisdom used in the corresponding cultures: "Hoxha", "Khwaje", "Hodja", "Hojja","Hodscha", "Hodža", "Hoca", "Hogea". Nasrettin Hoca was a philosopher, wise, witty man with a good sense of humor. His stories have been told almost everywhere in the world, spread among the tribes of Turkic World and into Persian, Arabian, African and along the Silk Road to China and India cultures, later also to Europe. Of course, all these stories currently attributed to the Hoca for about 700 years haven't originated from him. Most of them are the product of collective Humor of not only Turks but also other folks in the World. Nasrettin Hoca is also well known in other countries. For example, in Greece (where he is known as Hoja Nasreddin), in many Arabic countries (Juha) and Iran (Mulla Nasreddin). Children, whilst still very young, become acquainted with this thirteenth century philosopher come teacher come imam. Or rather, they become acquainted with his anecdotes and stories, since they often contain sensible learning morals. It has to be said, though, that Nasrettin Hoca is also popular with adults. Today, almost 800 years after his death, Turks still have to laugh about – and reflect upon - his trickery, sharp intellect, ridicule, anecdotes, humour, his ability to play jokes on people, his depth of insight and resourcefulness. He could see the human element in every aspect of daily life and used his sharp intellect to make people aware of the flip side of the truth. Therefore his stories are as relevant today as they were back then. Unesco even declared 1996 ‘The year of Nasrettin Hoca’. He was given this honourable title later on in his life. Following his education, Nasrettin became an imam, just as his father had done. He had a great sense of humour, was very clever and had a solution to just about every problem and/or dilemma of his time. In some stories, however, Hoca behaves rather foolishly. It's suggested that he did this deliberately to play jokes on others. He loved surprising his fellow villagers by combining an important messages. 15 Sansal, B., a certified professional tour guide in Turkey, 1996 SOME OF HOCA'S STORIES HOW TO USE A DONKEY … Nasrettin Hoca and his young son were on their way to the market. Hoca was riding his donkey and his son was walking beside him. As they travelled such, they heard a few villagers talking about them. “Look at our Hoca, he is comfortably riding on his donkey and letting his poor little boy walk along. Shame on Hoca for making the boy suffer like that!” When Nasrettin Hoca heard this, he wanted to rectify what was perceived as his selfishness. He put his son on the donkey and he started to walk beside. Then shortly after, they met another couple of villagers. “Look at Hoca and his son!” they said, “these are the times we are living in. A young boy is riding on the donkey and his poor old father is sweating to keep up with them. Today's children have no respect for their parents.” Nasrettin Hoca found some reason in this comment and thought of another remedy. They both got off of the donkey and started to walk beside it. A little while later, a group of villagers, also going to the market, approached the procession of Hoca, the son and the donkey, all walking one after the other. “Hoca and his son have no minds, whatsoever”, they whispered, “they are both hot on their feet and the donkey is strolling along. Don't these people know what a donkey is for?” Hoca heard this and thought they had a point. The solution was clear. Both he and his son sat on the donkey. As they continued their trip, both of them sitting on the donkey, thinking to themselves that they have finally complied with all the opinions of the villagers, they met another of their acquaintances. He was not very happy to see both Hoca and the boy on a scrawny donkey. “Hoca”, he yelled, “don't you have any mercy? How is this poor little animal supposed to carry two people? Have some pity please!” Nasrettin Hoca agreed with this last remark as well. What were they to do? He shouldered the front body of the donkey and his son took on the back part, and they carried the donkey to the market place. THE SLAP Nasrettin Hoca was standing in the marketplace when a stranger stepped up to him and slapped him in the face, but then said, "I beg your pardon. I thought that you were someone else." This explanation did not satisfy the Hoca, so he brought the stranger before the qadi and demanded compensation. The Hoca soon perceived that the qadi and the defendant were friends. The latter admitted his guilt, and the judge pronounced the sentence: "The settlement for this offense is one piaster, to be paid to the plaintiff. If you do not have a piaster with you, then you may bring it here to the plaintiff at your convenience." Hearing this sentence, the defendant went on his way. The Hoca waited for him to return with the piaster. And he waited. And he waited. Some time later the Hoca said to the qadi, "Do I understand correctly that one piaster is sufficient payment for a slap?" "Yes," answered the qadi. Hearing this answer, the Hoca slapped the judge in the face and said, "You may keep my piaster when the defendant returns with it," then walked away. EAT, MY COAT, EAT The Hoca was invited to a banquet. Not wanting to be pretentious, he wore his everyday clothes, only to discover that everyone ignored him, including the host. So he went back home and put on his fanciest coat, and then returned to the banquet. Now he was greeted cordially by everyone and invited to sit down and eat and drink. When the soup was served to him he dunked the sleeve of his coat into the bowl and said, "Eat, my coat, eat!" The startled host asked the Hoca to explain his strange behavior. "When I arrived here wearing my other clothes," explained the Hoca, "no one offered me anything to eat or drink. But when I returned wearing this fine coat, I was immediately offered the best of everything, so I can only assume that it was the coat and not myself who was invited to your banquet." THE CAULDRON THAT DİED Nasrettin Hoca, having need for a large cooking container, borrowed his neighbor's copper cauldron, then returned it in a timely manner. "What is this?" asked his neighbor upon examining the returned cauldron. "There is a small pot inside my cauldron." "Oh," responded the Hoca. "While it was in my care your cauldron gave birth to a little one. Because you are the owner of the mother cauldron, it is only right that you should keep its baby. And in any event, it would not be right to separate the child from its mother at such a young age." The neighbor, thinking that the Hoca had gone quite mad, did not argue. Whatever had caused the crazy man to come up with this explanation, the neighbor had a nice little pot, and it had cost him nothing. Some time later the Hoca asked to borrow the cauldron again. "Why not?" thought the neighbor to himself. "Perhaps there will be another little pot inside when he returns it." But this time the Hoca did not return the cauldron. After many days had passed, the neighbor went to the Hoca and asked for the return of the borrowed cauldron. "My dear friend," replied the Hoca. "I have a bad news. Your cauldron has died and is now in her grave." "What are you saying?" shouted the neighbor. A cauldron does not live, and it can not die. Return it to me at once!" "One moment!" answered the Hoca. "This is the same cauldron which gave a birth a short time ago, a child is still in your possession. If a cauldron can give birth to a child, then it also can die. You believed that it gave birth, but now how come you don’t believe it died ?" And the neighbor never again saw his cauldron. Karagöz & Hacivat Karagöz and Hacivat is a Turkish shadow play taking its name from its main character Karagöz . According to a legend, they were working as construction workers in a mosque in Bursa. Although their satiric jokes entertained other workers it also held up the building of the mosque by their constant joking together. As a result it made the sultan very angry and anxious about whether Karagöz and Hacivat could encourage rebellion in others, so they were executed. The construction of the mosque was completed without them, but their comrades did not forget them and kept their jokes alive, telling them over and over. In time, the adventures of Karagöz and Hacivat gained a new dimension and the traditional Turkish shadow puppet theatre was born. Their monumental tomb stands in Bursa today. When the plays were first performed is unclear. As a thought, the origin of the shadow plays is accepted as southeastern part of Asia. According to the 17th century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi, the play was first performed at the Ottoman palace in the late 14th century. Another thought is, this play came into Anatolia after Yavuz Sultan Selim, who had conquered Egypt in 1517, had brought the shadow play artists to his court. The shadow play was the most important entertainment of the Ottoman period and was widely performed for the public and in private houses between the 17th and 19th centuries particularly during Ramazan, and at circumcision, feast festivals, coffee houses and even in gardens. The central theme of the plays are the contrasting interaction between the two main characters: Karagöz represents the illiterate but straightforward public, whereas Hacivat belongs to the educated class, speaking Ottoman Turkish and using a poetical and literary language. Karagöz play is played depending on the talent of an artist. Moving the design on curtain, voicing them, dialects or imitations are all made by the artist. The subjects of Karagöz plays are funny elements with double meanings, exaggerations, verbal plays, and imitating accents. There is always satire and irony. The main characters of the play are of course Karagöz and Hacivat. Karagöz is uneducated but honest and represents the public morals and common sense, the ordinary man in the street, and is straightforward and reliable. He is almost illiterate; usually unemployed and embarks on money earning projects that never work. He is often kind of rude, deceitful, lewd, and even violent. . You can recognize him by his turban, his bald head and his black beard. His left arm is longer than the other one. His friend Hacivat instead is the opposite of him; he is educated in a Moslem theology school, speaks Ottoman Turkish and uses poetical and literary language. He's very clever as well. Other characters in these plays are the drunkard Tuzsuz Deli Bekir with his wine bottle, the longnecked Uzun Efe, the opium addict Kanbur Tiryaki with his pipe, Altı Karış Beberuhi (an eccentric dwarf), the half-wit Denyo, the spendthrift Civan, and Nigâr, a flirtatious woman. There may also be dancers, and various portrayals of non-Turks: an Arab who knows no Turkish (typically a beggar or sweet-seller), a black servant woman, a Circassian servant girl, an Albanian security guard, a Greek (usually a doctor), an Armenian (usually a footman or money-changer), a Jew (usually a goldsmith or scrap-dealer), a Laz (usually a boatman), or a Persian (who recites poetry with an Azeri accent). All actions is runing in the quarter of İstanbul, because it represented the only true unit of social life under the Ottoman Empire. The city was never anything but an agglomeration of quarters, or precincts, each with a life all its own. It would be necessary to have lived in that era, which after all is not so very long ago, to understand the social omnipotence of the quarter which through its stracture, its organization and its collective conscience, regulated the life of the individual down to its smallest details. It was the quarter which, adapting itself to the contours of the land and centering about a mosque , lent a picturesque aspect to the great city, the urban unity of which was lost amidst a multitude of tortuous by ways and shadow culs de sac. In addition to its mosque, where some pious and generous donor had founded a library, the quarter had its school, its fountain its inn and occasionally its convert; numerous cafes, a standing corps of fireman, a reeve, who concerned himself with everything, its night watchman, watercarries, rich people and poor people, devout persons and libertines, decent citizens and rogues. SOME REPRESENTATIVE KARAGÖZ SCENARIOS16 THE PLEASURE TRIP TO YALOVA: Çelebi, the dandy, wishes to take a trip with his sweetheart to the Spa of Yalova. He therefore buys a large sack and a jar in which to put provisions for the journey. While he is making last minute preparations, Karagöz appears and teases her with stupid, nonsensical stories the young woman who has remained behind with the sack and the jar. For instance he tells her that her boy friend is dead and somebody has set fire to the sea and that Çelebi has been burnt, or that somebody though that he was a mouthful of food and has swallowed him, and so on. Taklits appear, all of whom wish to go on the same trip and are hidden one after the other by the obling girl in the sack and the jar. Among them is the girl’s other lower. When Çelebi comes, he puts all these people out of the jar and sack where they had been concealed, hopping to travel without paying their fare. THE PUBLIC SCRIBE: Unemployed, Karagöz becomes a public scribe in a haunted shop, where he writes nonsensical latters for his clients. At length he is seen to be haunted by a djin, hired for this purpose by Hacivat. 16 And, Metin, Traditional Turkish Shadow Theatre KARAGÖZ IN THE POETRY CONTEST: Karagöz enters a poetry contest among minstrels and beats all the other poets who present themselves having droll manners and costumes. He wins the prize, not by his talent in improvising poems on given rhymes and themes, but by his rudeness and violence. THE SWING: Karagöz and Hacivat hire out a swing to their customers and Karagöz swindles his partner, Hacivat of his share of the takings. To check up on Karagöz’s story, that nobady has come to be swung. Hacivat disguises himself as an old woman. A jew comes and feigns death and there follows a burial scene in which other jews bring in a coffin only to be frightened away by Karagöz who heaves the dead jew out of the coffin. THE PUBLIC BATH: Çelebi, the dandy, has inherited two public bath, each of which is run by a woman who is a notorious lesbian. The woman become angry and leave the bathhouses. Now Çelebi wants them back as they are efficient and ask Hacivat’s help. In this way, they are reconciled. Karagöz, being lealous, watches his wife through the window of the bathhouse. A fire stars in the bathhouses and everybody comes out including Karagöz with half his beard burnt, since the Persian henna-seller has mixed yellow arsenic with the henna. Karagöz is distressed because when there is no bath house he will loose the customers for his spice shop which is opposite. THE PURSE OR KARAGÖZ, THE WRESTLER: The rich father of a girl dies and makes it a condition that his future son-in-law should be able to bend his doughter’s arm. This is no men feat as the girl is very strong. For a long time, people have tried but none have succeeded. In the end, they ask Hacivat whether he knows, of anybody who could accomplish this. Karagöz succeeds in doing it but the girl’s mother makes another condition; that he should prove himself unbeatable by all other wrestlers. Karagöz accepts this challange also whereupon all the standard characters of the screen wrestler are beaten. So Karagöz wins the girl. THE GARDEN: Çelebi has a garden. He entrusts Hacivat with the running and concern of the garden and Hacivat recommends that he make it into a pleasure garden. Karagöz wants to get a job as a pipe player in the garden but Hacivat, who is the manager, refuses. Several people come and enter the garden. When Matiz comes, he says that in a respectable neighbourhood dancing and merriment cannot be allowed so he shuts the garden down until a licence is obtained. TAHIR AND ZÜHRE: A rich gentleman, following the advice of Hacivat, hires Karagöz as major in his household. The rich man’s doughter, Zühre and his nephew, tahir, love each other. But the step mother of Zühre also loves Tahir, so in order to stop their marriage, she decides to change her husband’s mind by magic. She enlists the help of Karagöz to put an amulet with magical properties on her husband, in order to make him change his mind upon awakens. In fact, he does change his mind upon awakening and separates the lovers. But later the truth is revealed, and Karagöz explains everything. Not only are the two lovers united but, as a reward, Karagöz also marries a girl from the richman’s household. Keloğlan Keloğlan is a very well-known Turkish folk stories hero. He is a poor and an orphand boy who lives with his elderly mother. He is a lazy boy who works unwillingly with the force of his mother and keeps the job grudgingly, because of his stupidity and forgetfulness to work hand side is one of the propagator. Unexpectedly, the power status remained in a human or animal for helping them with the support of the extraordinary power of fortune turns. Keloğlan chopper's fate, ruthless, cunning in the face of injustice to those who had gained the temperament and intelligent behavior may also change. As a well-known character - also known as keleşoğlan - Keloğlan has a problem of being bald from birth who seems incompetent, in development of cunning,we understand that he is brave and resourceful, and finally reached his happiness. Sensible and sensitive Keloğlan gets the big rewards at the end of his various experiences all the time. Although richness is the main element all of the stories, Keloğlan’s mother feels happy when her son has lost the magical bowl which has supplied them gold all the time because she does not want his son to be greedy and ambitious. He can set up most of the Anatolian people fall, but the biggest prize with the opposite hand it can also, virtuous, discreet, a little naive, a little romantic, highly practical minded representative. He is unlike superior to people who take place in several tales of princes.He always makes people to forget his cunning of poverty and isolation by helping others with the courage. “Keloğlan has various functions in the realm of thoughts and actions of the folk who identify with him. Keloğlan not only is entrusted with the duty of bringing about good government, by means of giving guidance both to the Sage and the Ruler, but also, he must show the population how to convert dreams into reality. As usual, his actions may well be outside the tired norms, inspiring and encouraging creative thinking.” Güler Soytaş; Antalya. 1995 In the Turkish fairy tales, the hero Keloğlan two seemingly opposite interests. The first is usually the end of the beginning of the story remains unchanged. Wealthy, powerful man after the fact to protect the identity. In some tales Keloğlan, help with the support of the good-hearted . In both cases the result Keloğlan is a wealthy and powerful, revenge aspirations expressed are those persecuted powerful man and his mother would be happy with a life regains. In Arab countries, Iran, Caucasus, Central Asia, Russian and Western Europe the “Keloğlan Tales” can be seen ,too. Names, personality, looks different, although they all have similar aspects of this tale as the hero is seen. Although not much in the fairy tale itself shows here involved would be effective. An important place in Turkish folk literature as compiled by Keloğlan tales, and many researchers have been published. Some of the Keloğlan stories.. KELOĞLAN AND MAGICAL BOWL Once there was a bald boy, named Keloğlan. His old, poor mother was addressing him as “Bald son, cute son”. One day Keloğlan went fishing to catch some fish. “I can catch a few fish for me and my mother and shall be full up that evening”, he thought. On the edge of the river he threw his fishingline to the water, soon he caught a very big fish in the afternoon. Its eyes were as light as a glass, and its scales were as brilliant as silver, it was a very beautiful fish. Keloğlan carved its scales, and went to cut its belly and clean it. It’s was then he saw a big bowl inside the fish. He felt very happy “I shall take both the bowl and the fish to my mother”, he said. He wanted to wash the fish by the bowl of water and pour the water in the bowl on the fish but at that time he saw that gold was flowing from the bowl instead of water. He tried a few times to be sure.He saw again that gold was flowing . “I think it is a magical stone, I should tell my mother right away”, he said and he ran all the way home as fast as he could. Keloğlan soon became very very rich, even the king of the country was poorer than him. He built a wonderful palace and he had a lot of servants and he was eating the most delicious meals. After sometime, Keloğlan started to be spoiled by richness, he wasted a lot of gold unnecessarily. He even did not listen to his mother’s warnings about it. “I have a magical copper bowl and I can do anything and everything I want” he said. People started to lose their interest in him because of his pride and ambitions. People have now commented that ‘Keloğlan was better in his old days, now we cannot know him, he is a spoiled and very ambitious person at present’. One day Keloğlan came to the edge of the river “Gold does not finish, I can build a palace here too” he thought and at that moment his magical copper bowl in his hand fell into the water. Keloğlan jumped into the river to catch it, but Keloğlan was not a good swimmer and he nearly drowned. He was able to rescue himself after sometime, but during this time, thieves have stolen all the gold. Keloğlan cried and went back to his home, he told his mother what happened on the edge of the river and how he lost the magical copper bowl and the thieves stolen all his gold. “Don’t worry, my dear son, that magical copper bowl was not your right. You did not gain it by your work and effort. Besides, you were very spoiled and proud. Leave it. You will be rescued of looking down people like that” his mother said. Keloğlan was comforted by his mother and found what mother said was right . KELOĞLAN AND HIS SQUIRREL FRIEND Keloğlan and his mother were very poor. Sometimes there were not much food at home and that day Keloğlan took his basket and go to the forest to pick mushrooms so that his mother could cook it that evening. That day was dull and grey, there was fog and some rain, Keloğlan went to forest to pick some mushrooms. He placed some into his basket and some he ate , he then sat under a tree to rest for a while. He saw a squirrel when he looked up. The squirrel was sitting. When it saw Keloğlan squirrel jumped from the branch to the ground and it went to the side of Keloğlan and started to cry. Keloğlan kissed the squirrel and cared for it as he tried to comfort the squirrel. “What a pity! I have not found a friend like you so far.” The squirrel said. Keloğlan also felt sorry and told of his poverty to the squirrel. The squirrel listened to Keloğlan and it understood his sadness. “Let me do you a favour , but please follow me to the end of the forest.” the squirrel said. So the squirrel and Keloğlan both walked for hours to the end of the forest, as the forest began to clear and the sky began to be more visible, on the ground below the rocks began to appear. “Go to the rocks and partridges will welcome you and ask you three questions. If you know the answers, you will see what you have gained.” the squirrel said. Keloğlan approached the rocks and three partridges welcomed Keloğlan. “We have three questions for you, if you know them, you will gain two large jugs of gold.” the queen partridge said. “Ask the question.” Keloğlan replied. Queen partridge showed a cherry tree and asked how many cherries are there on the tree? “It’s easy, it’s as much as your golden feather.” he answered. “Why do you say that?” she asked. “Count it and see.” Keloğlan answered. The queen partridge accepted his answer. The second question was about where the central point of the world is? “The place you stepped on, you can measure it.” Keloğlan answered. The partridges accepted his answer. Then the queen partridge took two hazelnuts in her hands. “Which one is heavier? Answer it, please.” she asked. “The hazelnut which has sunk into the water is much heavier.” Keloğlan answered. After the partridges accepted his correct answer they gave him two jugs of gold. Keloğlan ran to his home and gave the gold to his mother and then went to find the squirrel. He soon found the squirrel and it was crying. “I am a sultan’s daughter and there is a magic over me and I am like that.” The squirrel said. Keloğlan said to the squirrel he would help him. “It’s very difficult.” the squirrel said. “You will go to the mountain of Emerald and you will fetch the emerald water from a cave where a dragon has lived.” the squirrel continued. Keloğlan took with him a sharp sword from the town and soon arrived at the Mountain of Emerald. He took out his sword and took a few swings and slashed the snakes which guarded the cave. The dragon which was alerted by the alarmed voices of the snakes as the snakes were killed, went to investigate. Keloğlan immediately went into the cave and filled the bottle, he brought with him, with the emerald water. Once he has filled the bottle he went off to find the squirrel. The squirrel welcomed Keloğlan who come running back in joy. The squirrel took the bottle from Keloğlan and started to drink the water. Soon after drinking the water, the squirrel soon turned into a very beautiful girl. The girl and Keloğlan went to her father’s palace and then her father presented to Keloğlan much gold. Keloğlan and his mother lived to the end of their life in richness and joy. KELOĞLAN AND GIANT In the town was a hut where Keloğlan and his mother used to live in. Keloğlan was smart but a bit lazy, but that day, he slept and stayed at home and he just ate and drank whatever food or drink he could find at home. His mother used to wash the clothes and try to feed her son as well as herself and they would live in difficulties. People called him Keloğlan because he did not have any hair on his head. One day, he went out and went to the bazaar. He saw a man in the bazaar. The man shouted and said something, people all turned and listened to him. Keloğlan wanted to know what the man said. “There is work which needed to be done. I need someone for it, I will give 100 gold to the person who can perform this work. Who wants this work?” he shouted. Nobody wanted the job, so Keloğlan thought that 100 gold was a good amount. “I will accept the work”, he said. The man looked at Keloğlan, “Son, it is a very hard work. Only the clever, the talented, and brave people can do it, are you sure?” he quizzed. But Keloğlan wanted to do it. People laughed at him. “All right, the job is yours. How do you want your money, in advance or later?” the man asked. “I want it now because I would like to give money to my mother” He said. Keloğlan went back home and told his mother what happened in town at the bazaar. He gave the money to his mother and then said bye. Then he met the men in the caravan and they acted together. Caravan has been on the road for two days. 3rd day, Keloğlan got tired because journey was very hard. When the sun set, they took a break. Keloğlan became happy. He wanted to rest a bit. “There is a well over there. Can you see it? ” the chief asked. “Yes, I can see it. What happened?” Keloğlan asked. “Go there. You are not a coward, aren’t you?” the chief asked. “No, I am not a coward” Keloğlan said and went to the well. The men gave him a rope and then Keloğlan abseiled down the well. As Keloğlan approached near the bottom he could see a door in the wall of the well. A man came to the door and got hold of Keloğlan and pulled him inside. Keloğlan did not understand what happened or why this man was there inside the well. Inside there was a very beautiful garden and there was a very beautiful palace in the garden. Also there was a very beautiful girl in it. There was a man on the side of the girl and he was very ugly. Also there was a peacock among the flowers as Keloğlan watched them, he then suddenly heard a very loud voice behind him. Keloğlan turned and saw a big giant. “Hey human, tell me which one is more beautiful.” the giant said. Keloğlan was scared at first then responded “Depending what heart loves and what heart loves is beautiful”. Giant liked this answer, the giant asked him again “This girl is beautiful, that peacock is very nice and this man is very ugly. What do you think?”, “What heart loves is beautiful” Keloğlan answered. Giant liked this answer again, “Well done, you are a smart boy.” giant said and he brought three pomegranates, take them with you and return back to your home.” The giant said and then giant went away. Giant would ask this question to everybody who went down the well and entered into the garden. People would choose one of them, so therefore, giant has not liked these answers so far. But it liked the Keloğlan's respond. Keloğlan went to the door and peered out of the door and saw a water carrier which led up the well to the surface. The men in the caravan wanted to have a drink of water so went to the well to get some water and Keloğlan held onto the water carrier and went up. The men were surprised when Keloğlan came back from the well. It was necessary to sacrifice something to take the water from the well, and the men were sure Keloğlan was a victim and that he could not come back. “How come, when nobody has ever come back from the well so far”, men said. “My way of coming back is not so important, but the result is important.” Keloğlan answered. The caravan arrived in the country where they could buy things and the men loaded the goods they brought onto the horses and came back to their own country and town. Keloğlan went back to his home and saw his mother washing laundry again. They had a dinner and after the dinner, Keloğlan divided the pomegranate into two pieces to eat. When he has cut the pomegranate he saw that every piece has precious jewellery. Keloğlan understood its value and he sold them piece by piece. Keloğlan and his mother became rich and lived happily. SOURCES Alstadt, Audrey. The Azerbaijani Turks, Hoover Press, 1992 Asim, Necib, Orhon Abideleri (Istanbul, 1341/1925); H. N. Orkun, Eski Turk Yazitlari (Istanbul, 1936-1941) 4 cilt. (check: T. Tekin, A Grammar of Orkhon Turkic (Bloomington, 1968). Indiana University Uralic and Altaic Series, Volume 69.) Atalay, B., Divanu Lugat-it-Turk (Ankara, 1939-1941). Bayram, M. "Ahi Evren, Şeyh Nasyrud-din Mahmud, Nasreddin Hoca'dır" , 21 December 2000 Branson, L., "How Kremlin Keeps Editors in Line" The Times (London) 5 January 1986) P. 1; Martin Dewhurst and Robert Farrell, The Soviet Censorship (Metuchen, New Jersey, 1973); Bulletin, AACAR ,"Nationality or Religion? Views of Central Asian Islam" Fall 1995. Clement Victoria, "Türkmenistan" Countries and their Cultures, M. Ember and C.R. Ember, Eds. (Macmillan Reference, 2001) Vol 4, Pp. 2275-2287 contains a working bibliography on the Türkmen. Dadaszade Memmed, "Dede Korkut destanlarida Azerbaycan etnografiyasina dair bazi malumatlar" Azeraycanin Etnografik Mecmuasi (Baku) No. 3, 1977. Soviet Anthropology and Archeology (New York) Vol. 29, No. 1 (Summer 1990). DeWeese Devin Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tükles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition. (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994 Series "Hermeneutics: Studies in the History of Religions"), Golden, Peter B "Codex Comanicus'" in Central Asian Monuments (Istanbul: ISIS Press, 1992) for some odes to Jesus. G. L. Lewis, The Book of Dede Korkut, Tr. (London, 1974). Gölpınarlı A. (1900-1982), Melamilik ve Melamiler (Istanbul: Pan Yayınları, Gri Yayın Dizisi Tıpkıbasım: 1992) (First printing: 1931). Goffman, D., “The Ottoman Empire and Early Europe” Ball State University, Cambridge University Press, (2002) Grousset, R. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1991, Gulam Memmedli, Molla Nasreddin (Baku, 1984); Hacip, Yusuf Has, Kutadgu Bilig. R. R. Arat, Editor, (Ankara, 1974) (2nd Ed.). KB is translated into English as Wisdom of Royal Glory by R. Dankoff (Chicago, 1983). Ibadinov Alishir, "Sun is also Fire" Central Asian Monuments (Istanbul: ISIS Press, 1992) Kasgarli Mahmut, Diwan Lugat at-Turk (DLT). For more info about “Kasgarli Mahmut”: Kahar Barat, "Discovery of History: The Burial Site of Kashgarli Mahmut" AACAR BULLETIN (of the Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research) Vol. II, No. 3 (Fall 1989). Lewis, G. The Book of Dede Korkut. Penguin Books, 1974, M. T. Choldin, A Fence Around the Empire: Censorship of Western Ideas under the Tsars (Durham, 1985); B. Daniel, Censorship in Russia (Washington, 1979). Minahan, James B. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Press, 2000 Mirahmedov, Aziz, Azerbaycan Molla Nasreddin'i (Baku, 1980); Mirza Elekber Sabir, Hophopname (yayina hazirlayan) Memed Memedov (Baku, 1980); Nihal Atsiz, Turk Tarihinde Meseleler (Istanbul, 1975). Omeljan Pritsak, Studies in medieval Eurasian history (London: Variourum reprints, 1981) Paksoy, H.B., Reprinted in International Journal of Central Asian Studies, Essays on Central Asia, (1998) Paksoy H. B., "Elements of Humor in Central Asia: The Example of Journal Molla Nasdreddin" Turkestan als historischer Faktor und politische Idee. Baymirza Hayit Festschrift, Prof. Dr. Erling von Mende, ed. Koln: Studienverlag, 1988 Paksoy, H.B. , "Turkish History, Leavening of Cultures, Civilization" [ Essays on Central Asia]. Paksoy, H. B. "Alpamys zhene Bamsi Beyrek: Eki at bir dastan" Kazak Adebiyati (Alma-Ata) No. 41, 10 Oct 1986. Fadli Aliyev, Ankara Turk Dili No. 403, (1985) Paksoy, H. B., "Introduction to the Dastan Dede Korkut" Soviet Anthropology & Archeology (New York) Vol. 29, No. 1 (Summer, 1990). Cf. Central Asia Reader. Paksoy, H. B., "Elements of Humor in Central Asia: The Example of the journal Molla Nasreddin in Azarbaijan." Turkestan als historischer Faktor und politische Idee. Prof. Dr. Erling von Mende (Ed.) (Koln: Studienverlag, 1988). Paksoy, H. B., ALPAMSH: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule (Hartford: Connecticut, 1989). Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research Monograph Series. P. N. Boratav, . Halk Hikayeleri ve Hikayeciligi (Ankara, 1946) Preston, W.D., “A Preliminary Bibliography of Turkish Folklore”, JAF, (1945) R. Dankoff with J. Kelly, Compendium of Turkic Dialects (Cambridge: Mass, 1982-1985). Sharpe, M. E. Sharpe, The Rediscovery of History (New York/London:, 1994) Sumer, F., "Oguzlara Ait Destani Mahiyetde Eserler" Ankara Universitesi DTC Fakultesi Dergisi 1959; a.g.y., Oguzlar/Turkmenler (Istanbul, 1980). Sümer F. , The Book of Dede Korkut, , A. Uysal and W. Walker, Trs. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972); Togan, Z. V., Oguz Destani: Resideddin Oguznamesi, Tercume ve Tahlili (Istanbul, 1972). Togan Z. V. T, "Turk Milli Dastaninin Tasnifi" Atsiz Mecmua, Mayis, Haziran, Temmuz, Eylul, 1931. Togan, Z.V., Hatıralar (Istanbul, 1969) Torday, L., Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. The Durham Academic Press, 1997 W. Radloff, Proben der volkslitteratur der Turkischen stamme sud sibiriens (St. Petersburg, 18661907) Yamauchi, Masayuki, Translation in Central Asia and the Gulf., Ed. (Tokyo: Asahi Selected Series, 1995)