Income Statement Analysis PROFIT UNM Lecture 9-12

advertisement

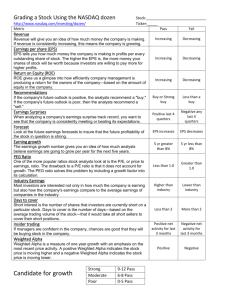

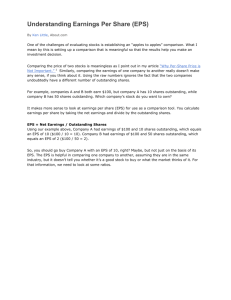

Income Statement Analysis PROFITS Alexander Motola, CFA Alexander Motola, 2013 1 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” Differential Disclosure is when a company paints a different picture in its SEC filings compared with other informational releases Large deltas in disclosure can point to poor management quality (pg. 45) – if SEC filings are “more accurate” why read anything else? There is a lot of qualitative information in press releases (as well as better timeliness) and shareholder reports Alexander Motola, 2013 2 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” Case Study of P&G (pg. 45) From 1983 to 1984, operating income declined, which is NOT mentioned in the annual ◦ Tax rate changes and special items drove a modest increase in Earnings per Share (EPS) Pgs. 45-46 give a excellent example of how qualitative research can verify and illuminated issued raised quantitatively (through financial/forensic analysis) Alexander Motola, 2013 3 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” Case Study of CVGT (pgs. 46-49) Big earnings (+25%) and revenue increases (+70%), but EPS was -5% ($0.40 vs. $0.42) Let’s examine these in order: ◦ Big revenue increase is good, clearly. However, 46% of sales were to 1 customer (Burroughs) who also had other incentives to buy stuff (owned warrants) and who was private labeling it (likely lower margin for CVGT) Alexander Motola, 2013 4 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” Some inputs were on allocation because CVGT was dependent on a sole provider for 2 important items Could severely impact future revenue growth Could be good: imagine if they could have made as many as they wanted The AMEX thing is weird, it feels like advertising or even channel stuffing (also something to check with Burroughs on as well). Would like to know how much of revenue came from this (pg. 47)? Alexander Motola, 2013 5 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” When revenues grow rapidly, you normally expect margins to expand – why? Hiring usually lags growth (lower opex/cogs) Advertising leverage Manufacturing efficiencies, procurement efficiencies Sometimes this doesn’t happen Extreme discounting Like with the iDevices, airfreight to meet demand ate up a lot of margin Large customer discounts or other low margin distribution changes (getting into Wal-Mart) I can’t find the SEC filings for CVGT, so we don’t know exactly what happened with margins Alexander Motola, 2013 6 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” If revenues grew 70%, but net income only grew +25%, then we know margins went down (but not necessarily which ones or how much); this is another way of saying expenses grew faster than 70% Year over Year (YoY) ◦ The biggest problem is obviously the shares outstanding. o’Glove doesn’t give us a ton of information, but we can figure this out, based on the formula for EPS [EPS = (net income/shares outstanding)] Alexander Motola, 2013 7 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” [EPS = (net income/shares outstanding)] ◦ For 1982, we know that net income was $11.9mm with EPS of $0.42 (pg. 47) ◦ For 1983, we know that net income was $14.9, with EPS of $0.40 (pg. 47) ◦ We also learn that CVGT has 36mm shares outstanding in 1983, +1.5mm warrants, for a total of 37.5mm ◦ 1983 EPS of $0.40 = ($14.9mm/37.5mm) ◦ 1982 EPS was $0.42, Net Income was $11.9mm, so SO must equal 28.33mm Alexander Motola, 2013 8 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” 1982 EPS was $0.42, Net Income was $11.9mm, so SO must equal 28.33mm ◦ That means Shares Outstanding increased 32% yoy, or each share you own is now worth 25% less than it was worth (you were diluted) ◦ Presumably, the company got a lot of money for an offering, but there’s other ways to grow share count which are bad for investors Alexander Motola, 2013 9 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 4 “Differential Disclosure” The qualitative work covered on pg. 48-49 shows that CVGT made a “deal with the devil” to grow revenues in 1983 from Burroughs, but ultimately gave the technology to them. CVGT was ultimately bought by Unisys (which was Burroughs after they changed their name), but CVGT investors didn’t do well UIS had one of the worst returns on equity of any company in US history (poorly managed) Alexander Motola, 2013 10 More on Margins Margins are a % of revenue (common sized income statement) The most important margins (we covered this earlier) are: Gross Margin, Operating Margin, and Net Margin. GM and OM can be used to compare within and across industries These 3 margins are what is being referred to when the “profitability” of a company is being discussed Alexander Motola, 2013 11 More on Margins Negative GM is rare, but it means that a company is selling goods in total for less than it costs to make or buy them; this is unsustainable Companies with high fixed costs generally have volatile GM and companies with variable GM usually have more stable GM Alexander Motola, 2013 12 More on Margins If GM improves, then – all else being equal – OM improves, and NM improves ◦ Be sure to understand where the improvement or deterioration is coming from ◦ If you calculate growth rates (YoY, or even QoQ) for all line items (revenue and each expense), then these will literally “jump off the page” at you, and the margin % can help understand the magnitude Alexander Motola, 2013 13 More on Margins For investors, rising margins are great (assuming they are rising for the right reasons) ◦ Company grows (+ve) (business is good and/or well managed) ◦ Margins expand (+ve) (growth and mgmt leverage and control expenses) ◦ Earnings grow faster than revenue (+ve) (direct result of margin expansion) ◦ Often equals earnings surprises (+ve) (analysts underestimate margin exp) ◦ Earnings estimates get revised higher (+ve) (analysts try to correct) ◦ P/E multiples (discussed later) expand (+ve) (investors value the stock more) This creates a situation where the stock price grows much faster than revenues/earnings, and translates into huge investor profits Alexander Motola, 2013 14 Shares Outstanding Shares Outstanding = how many pieces the ownership pie is divided into ◦ Fully Diluted – includes options, warrants, converts, etc. Used to calculate EPS if Net Income is >= 0 ◦ Basic – only issued shares, used to calculate EPS is Net Income is < 0 ◦ Most companies grow SO by 1.5%-2% due to options issuance to employees ◦ Equity offerings trade more shares outstanding for cash, which can be used to growth the company ◦ If SO shrinks, then each share is worth more Alexander Motola, 2013 15 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Non-Operating/Non-Recurring Income It’s pretty easy to do a basic model (income statement) of a company – you just copy the income statement into Excel, and divide net income by shares outstanding, get EPS Where does the model add value? ◦ Incremental information ◦ Analyzing routine information in a different way ◦ Marrying the qualitative to the quantitative for additional insight Alexander Motola, 2013 16 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Non-Operating/Non-Recurring Income Incremental information “If you believe Standard & Poor’s Stocks Reports and Moody’s Handbook of Common Stocks, those two reference bellwethers, in 1982 Pepsico (PEP) reported $2.40 per share which rose to $3.01 the following year, for an increase of 25 percent. But subscribers to The Value Line Investment Survey, an equally reputable publication, were informed that the 1982 earnings did not come to $2.40, but rather to $3.24 and 1983’s to $3.01, for a decline of 7% percent” (QoE, pg. 55) Analysts make choices; this difference was driven by choices in how to handle “charges” – unusual and supposedly non-recurring expenses related to write downs, mergers, and other “one time events” Alexander Motola, 2013 17 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Non-Operating/Non-Recurring Income There is no “right or wrong” answer to handling this, it’s the analyst’s judgment based on their research It is important to be consistent in how you handle modeling items or comparability gets disrupt and the value of your model becomes less PEP did grow EPS 25% and decline 7% in the same year, in accounting terms; the key is to understand why Even if the “Street” choses one method, you might not agree – which is fine, just be prepared to provide your rationale. Some companies have a long history (UIS – Unisys, mentioned in the earlier chapter) of taking “non-recurring charges” every single or nearly every quarter – is that truly “non-recurring”? Alexander Motola, 2013 18 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Non-Operating/Non-Recurring Income What’s the attraction of “charging off” expenses? ◦ Wall Street usually ignores the charges, resulting in a higher pro forma EPS, which would normally – over time – translate into a higher stock price ◦ Being overly aggressive with charges (“The Big Bath”) creates a “cookie jar” where expenses charged off can be reversed in future period to increase earnings (confused – ask the question) ◦ Tiny amounts can matter Alexander Motola, 2013 19 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Non-Operating/Non-Recurring Income Let’s use CVGT’s #s as an example 1982 EPS was $0.42, Net Income was $11.9mm, SO equal 28.33mm How much “accounting” needs to be done to get the 1982 EPS from 42c to 43c per share? ◦ $0.425 will be rounded to $0.43 ◦ 0.425 (necessary EPS) * 28.33 (SO) = $12.040mm in Net Income ◦ 1983 Net Income was $11.9mm, so if the CVGT CFO can find ($12.040 – 11.9 = ) $140,000 (after tax), he just earned another penny per share, perhaps meeting or beating expectations… Alexander Motola, 2013 20 Quality of Earnings, Ch. 5 Other Thoughts As covered last lecture, revenue recognition and expense recognition matter a lot ◦ Most any number can be manipulated DSOs can be factored, and this is often not disclosed. Factoring creates the appearance of high collections but at a cost (but one not obvious to investors) ◦ Channel stuffing happens… a lot ◦ Think about the motivations (proxy, meeting expectations, pride, etc.) – how much stock do the C-levels own? ◦ % of completion allows a huge range of possible revenue and expense recognition; companies that use this for a material part of their revenues often sell at a multiple discount for this reason Alexander Motola, 2013 21