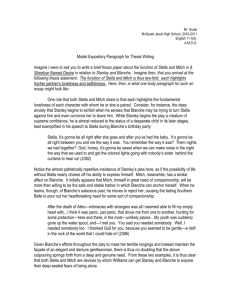

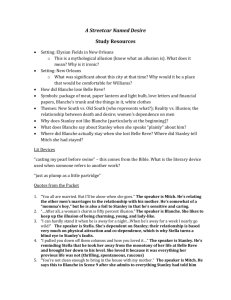

Although Williams's protagonist in A Streetcar Named Desire is the

advertisement