Civ-Mil-Pol-101-Overview-FG-final-150325

advertisement

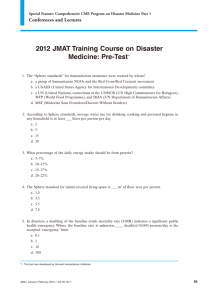

Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Awareness Module Facilitator Guide © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior written permission of the Australian Civil-Military Centre. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to info@acmc.gov.au with ‘CMP Interaction Overview’ in the subject line. Acknowledgements The Australian Civil-Military Centre (ACMC) gratefully acknowledges the contributions to this training package from: Australian Council for International Development Australian Defence Organisation Australian Federal Police Attorney-General’s Department Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade International Committee of the Red Cross Lowy Institute for International Policy Armed Forces of the Philippines RedR Australia United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs World Vision Australia. Information for facilitators Welcome to the Facilitator’s Guide for Civil-Military-Police InteractionOverview Awareness Module produced by the Australian Civil-Military Centre. It draws on information provided by the organisations noted in the acknowledgements and is a stand-alone package that provides core concepts. Additional detail is available in the following modules: 1. Australian Capabilities 2. International Capabilities 3. Cross-cutting Themes. The modules have been developed to assist personnel from government departments, non-government organisations and the private sector who would benefit from gaining a greater awareness of the key components of civil-military-police interaction in humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, conflict resolution, complex emergencies and peacekeeping operations. 2 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview This guide will help you prepare for the facilitation of training although it is not intended to prescribe how you will conduct training. The guide offers a range of material that you are encouraged to use, or adapt to suit your own training style and to meet the needs of your learners. There is no assumption that you are a subject matter expert. You are encouraged to share your own knowledge, understanding and examples with participants, while working within the framework of this guide. The guide is divided into the following sections: Section 1 – Course details Section 2 – Understanding your learners Section 3 – Delivery. Training package The civil-military-police interaction awareness training package comprises four modules: Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview (core module) and three optional modules: Civil-Military-Police Interaction - Australian Capabilities Civil-Military-Police Interaction - International Capabilities Civil-Military-Police Interaction - Cross-cutting Themes. The optional modules can be undertaken in any order and are stand alone. There is no expectation of prior knowledge. Feedback As this course will be reviewed regularly, we welcome any constructive feedback you may provide on how the content and activities might be improved. We will consider amending the courseware based on the feedback received. It would be appreciated if facilitators could also advise ACMC of when, where and to whom the course was conducted. Your comments can be forwarded by e-mail to to info@acmc.gov.au with ‘CMP Interaction Overview’ in the subject line. 3 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Section 1: Course Details Description The Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Awareness Core Module is a generalist, practical module developed to assist personnel who may have some contact with personnel from other organisations involved in humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, conflict resolution, complex emergencies and peacekeeping operations. This training has been designed responsibilities or delegations. for all personnel, regardless of Competency units Attending this course is for awareness purposes only and is not accredited or assessed for any unit of competency. Learning outcomes Following this course, the learners should be able to: Part 1: Introduction Describe what civil-military-police interaction means in this context. Outline why an understanding of civil-military-police interaction is necessary Identify Asia-Pacific disaster high risk areas Differentiate between civil-military-police coordination terminologies Describe key civil-military-police terms. Part 2: Australian capabilities 4 Outline Australian whole-of-government response structure and roles Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) Aid. Describe the roles and capabilities of Australian Aid Australian Federal Police (AFP). Describe the roles and capabilities of the International Deployment Group (IDG) Australian Defence Organisation (ADO). Describe the humanitarian and complex emergency roles and capabilities of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Attorney-General’s Department AGD). Describe the roles and capabilities of the AGD in disasters and complex emergencies Private sector. Outline the role and capabilities of the private sector in civil-military-police operations. Part 3: International capabilities International non-government organisation community and the challenges of civil-military interaction. Describe the features and mandates of the international non-government organisation community International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) roles and responsibilities. Describe the key elements and mandates of ICRC United Nations humanitarian coordination system. Identify the roles and responsibilities of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) and how it operates. Part 4: Civil-military-police interaction at work List the main civil-military-police actors Outline the different levels of civil-military-police interaction Identify differing organisational perceptions. Part 5: Planning Identify the key differences between civilian and military planning Identify the main issues involved when working in a complex environment. Part 6: Conclusion Outline the principles for civil-military-police planning and interaction Outline the key ways to achieve effective civil-military-police interaction Outline a checklist for effective civil-military-police interaction. This training is conducted at the awareness level. After training at the awareness level, participants will be able to demonstrate sufficient understanding of the issues, terminology and stakeholder relationships in the civil-military-police environment. 5 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Section 2: Understanding Your Learners This guide assumes course participants will be from your organisation and hence have a similar culture, focus and familiarity with applicable government legislation and your specific policies and procedures. It is also envisaged that at times, there will be a mixed group of learners from different organisations. It is particularly important to take into account the different backgrounds in this context. This unique context must be considered when sourcing appropriate material to aid facilitation. Consideration of this context will assist in understanding the various cultures, learner styles, motivations, experience bases, and personality types that personnel bring to the learning environment. An understanding of your organisation’s context will assist you to: use appropriate language and communication styles engage participants in the learning process maintain learning resources relevant to the participants’ workplace source appropriate learning material to support facilitation of the course maintain participant confidence in the facilitator and the learning material. Adult learning principles Adult learning principles have been incorporated into the course materials. The diverse workforce experiences brought to the training environment by personnel necessitate that all principles of adult education and learning be drawn upon during the conduct of the training. The following guidelines are provided for your information: 6 Adults are focused learners. They usually begin with strong ideas about what they want to learn and how they will apply it in their own workplace. Adults bring their own experience and knowledge to training and can offer valuable insights whether they are familiar with the subject area or not. They feel valued and are more enthusiastic to learn if experiences and knowledge of their own workplace context is acknowledged, respected and drawn upon during training sessions. ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Individuals may have formed strong preferred learning styles that will be a combination of listening, reading, doing, observing and thinking. Some adults may resist learning approaches or activities that do not suit their preferred learning style. Adults can be very self-conscious and therefore reluctant to participate in activities where they feel there is a risk of failing publicly. Learners should understand the intended outcomes of such activities and a positive environment be established to enable such activities to take place. Adult learning is encapsulated in the following principles: o o o o o o Feedback Active learning Reward Multi-sensory learning Open to negotiation Problem solving. Strategies for enhancing learning Crucially, learners need to connect learning directly to their own workplace. Some of the material provided may lead to considerable discussion and the sharing of experiences that cannot be covered in the allocated time. You need to exercise judgement in deciding when to curtail an activity or the acceptable extent of running over time. The quality of learning can be improved by: 7 encouraging learners to see how new information and theory will apply to their current or future duties providing opportunities for learners to construct their own knowledge through encouraging them to enquire, research and synthesise information in order to understand other perspectives providing direction, challenge and recommendations offering a range of activities so each learner has the opportunity to use a range of learning styles, acknowledging and drawing on the learners’ prior experience connecting prior experience to the current learning using additional appropriate examples and scenarios from your own experience (provided they are appropriate for the environment). ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Delivery implications – face-to-face delivery This module is designed for face-to-face delivery. It is ideal for collaborative learning and suits learners who learn best through interaction and immediate feedback. This style allows learners to raise issues that are most relevant to their own workplace experience and discuss the issues with others. This style is an excellent way to acknowledge and value the experience each learner brings to the group. However, alongside these benefits, there are limitations with face-to-face delivery which include: the need for learners to work at the same pace potential reluctance of learners to participate equally. There will be differences in the amount and type of experience each learner brings to training. You may find that some learners have significantly more experience and knowledge than others. You can manage this effectively by providing specific tasks that acknowledge their experience. These may include asking them to: suggest implications for the workplace raise previous strategies used in the workplace identify relevant support mechanisms in the workplace. The key is to recognise and use learners’ experience without letting them dominate or drive delivery for those who have less knowledge or experience. Make sure a range of opportunities is provided and show that each contribution is valued by giving it time and consideration. Managing expectations and difficult questions Some learners may assume you to be a subject matter expert. You are not expected to be; indeed it is probably not possible. Your role is as a facilitator, to guide learning. However, your efforts to research the topic using the references on page 12 and, other sources, will increase your knowledge of the subject and give you additional confidence to perform the facilitator role. 8 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview If you don’t know the answer to a question, say so and ask the group: ‘Is there anyone who is able to share their understanding of this issue?’ Alternatively, simply ask the group to note the question and invite them to research it and share the answer with the group. Currency and recency Despite the best of intentions, training materials date over time. If this occurs, acknowledge that the material was accurate at the time of publication and then make use of the knowledge in the room. You could also ask the question: ‘What would you do if this was pointed out in your usual workplace?’ On-line learning These modules are currently not intended for on-line learning or distance learning methods, however aspects of the course could be tailored for this purpose. 9 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Section 3: Delivery Suggested preparation Given that every class of learners is different, you can decide which sections should have more or less time allocated to them. Don’t feel you have to cover every slide, if the knowledge skills and attitudes are already present in your learners, skip it or quickly use as reinforcement. The length of this training is about four hours, so at least half a day should be allocated to preparation. Recommended preparation includes: Guiding Principles Collaboration (ACMC) for Australian Civil-Military–Police Reading Familiarising yourself with the learning outcomes for this module. These are listed in Section 1: Course details Reading the Learner Workbook Identifying and speaking with colleagues about potential examples, relevant documentation, policies and procedures. This information can be used to enhance group discussion Browsing current media for examples that could be used in discussion Skimming as much of the reference material as you have time for Finding out where you will be delivering and what equipment they have available Conducting a rehearsal or practice session. Facilitation resource checklist The following checklist is provided as a guide: Learner Workbooks Facilitator Guide PowerPoint memory stick Handouts (issue at the conclusion of training so not to be a distraction) including: o Same Space Different Mandates (ACMC/ACFID) o Military 101 Handbook (ACMC) Reference materials (leave on a table for learners to have a look at during breaks) including: 10 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview o Guiding o o o o o Principles for Australian Civil-Military-Police Collaboration (ACMC) Australian Defence Doctrine Publication 3.11 – Civil-Military Operations Australian AID Framework for working in fragile and conflictaffected states (DFAT Aid) Partnering for Peace(Australian Government/ACMC) New Zealand Defence Force Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Aide Memoire Strengthening Australia’s Conflict and Disaster Management Overseas. Data projector Whiteboard and markers Flip charts/ butcher’s paper and markers Computer Pens/paper Post it notes Nameplates/tags Catering Attendance lists with email addresses Evaluation/feedback. Delivery guidance During your preparation, you need to run through the slides, using the Notes for Slides section below. The notes in standard print can be read out or paraphrased and those in italics are for your guidance only. You may choose to add your own content, depending on your familiarity with the material. Refer to the learning outcomes as you prepare. The learning outcomes provide an overview of the content and the learning that will stem from each session. The Learner Workbook is a take away aide-memoire and contains the key slides for future reference. You should encourage participants to take notes in the Learner Workbook. You can also ask them questions during the session and get them to record responses in the Learners Workbook. About an hour is the maximum time without a break for optimal learning. Think about encouraging learners to stand up and have a stretch in place as well as formal coffee breaks between major changes in parts. 11 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview There is plenty of material to cover and your learners will be interested in some sections more than others. Remember this is an introductory module and every session and group of learners will be different. Tailor your delivery to meet the needs of your learners. You (and hopefully they) should have lots of fun! Additional information The Australian Civil-Military Centre is your first point of contact via info@acmc.gov.au with ‘CMP Interaction Overview’ in the subject line. ACMC should be able to put you in touch with subject matter experts. Links Australian Civil-Military Centre website: http://www.acmc.gov.au/ (Subscribe to the ACMC newsletter at the above address). Department of Foreign Affairs Aid website: http://www.aid.dfat.gov.au/Pages/home.aspx Australian Federal Police website: http://www.afp.gov.au/policing/international-deployment-group.aspx Australian Defence Organisation website: www.defence.gov.au Attorney General’s Department website: http://www.ag.gov.au/EmergencyManagement/Pages/default.aspx Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) website: www.acfid.asn.au/ RedR Australia-humanitarian training website: www.redr.org.au/ United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) website: www.unocha.org/ United Nations Women website: https://unwomen.org.au/ The Asia-Pacific Centre for Military Law website: http://apcml.org/ International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Australia website: 12 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview http://www.icrc.org/eng/where-we-work/asia-pacific/australia/index.jsp Australian National Action Plan on Women Peace and Security. Available at: http://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/women/publicationsarticles/government-international/australian-national-action-plan-onwomen-peace-and-security-2012-2018 13 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Notes for slides 1 Opening slide Show this slide as participants enter the room. When you are ready to start the session, change to the Welcome slide. 2 Welcome Outline emergency exits, toilets and breaks. You want to encourage discussion but point out there is limited time. This is introductory only and very general in nature. As shown on the welcome slide, these modules have been produced by the Australian CivilMilitary Centre to provide a basic awareness of the issues surrounding civil-military-police interaction from an Australian perspective, in a complex emergency or disaster. After training at the awareness level, participants will be able to demonstrate sufficient understanding of the issues, terminology and stakeholder relationships in the civil-militarypolice environment. The Learner Workbook is meant to be kept and used as an aide memoire and has spaces for you to write notes as we go through the session. You should expect to leave this session with more questions than you came with. My role here is as a facilitator, not a trainer. Activity Ask the group this question: Who can tell me what the difference is between a facilitator and a trainer? Answer: In a facilitated session, the onus for learning rests primarily with the participants themselves. As a facilitator, my job is to guide you through the learning material – what you get out of it is up to you. A facilitator may not be a subject matter expert. In a training session, the trainer must be a subject matter expert who transmits knowledge to the learners. The onus for learning lies with the trainer. Because learning is an individually controlled activity, it is often preferred to use a facilitator approach. 14 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview This session provides an overview of key aspects of civil-military-police interaction. More detail is available in the optional awareness modules that cover Australian Capability, International Capability and CrossCutting Themes. 3 Module topics Civil-military-police interaction as a topic is extremely complex; we will be covering the main issues only. You may think about taking things further through university study or doing the annual five day Civil-Military Interaction Workshop (CMIW) run by ACMC. 4 Need to know Activity Question: Why do we need to know about civil-military-police interaction? Ask the class for their answers, and then build the remainder of the slide with three clicks to bring up the suggested responses. Answer: Basically there is no choice. We live in the most disaster prone region in world. Natural disasters are becoming more frequent and more intense. Australia will increasingly be called on to work with other countries and organisations, in a whole-of-government approach. Consequently, we need to know how other agencies work, their organisational culture and what they can and can’t do, if we are to achieve a comprehensive, whole-of-government outcome. 5 Recent expansion of multi-dimension missions Build the slide with two clicks. This is the reality. This slide shows the continuing growth in complex operations. The left hand red arrow is a UN operation in the Congo known as UNOC. This was the first peak in UN peacekeeping and many lessons were learned as a result about the limitations of military peacekeeping. The 15 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview second arrow refers to UNTAC – the United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia, where there was a huge increase in the peacekeeping effort. Australia was heavily represented in a mission led by LTGEN Sanderson. Since that time, a range of complex and dangerous world events have all contributed to the current unprecedented demand for peacekeeping operations. 6 New reality Don’t get bogged down in detail in this slide. Tell the group that the overall impression is what matters. This is the reality of the operating environment. There are multiple actors and they may not all know how each other works – even though they may have to learn to work together. 7 The expanding network Build the slide with two clicks. In the past it was possible for a single agency to provide a response to a conflict or natural disaster overseas. On this slide the military is used to illustrate the point. Obviously a single agency response is no longer effective. Every situation is different, but on each occasion the actors will be a combination of formal and informal. It is now normal that a number of Australian agencies will be involved. It is now also normal that a number of nations will be involved too. Given this ‘new normal’ a key challenge is to find ways of working together more effectively. How this is done will vary from situation to situation. There is no single solution. Even so, there is an enduring truth in these complex responses involving many agencies and nations – ‘Nobody leads unless somebody leads’. Looking at the diagram, two terms invite further explanation: Interagency (the pink section) is also referred to as ‘whole-ofgovernment’ Multiagency incorporates civil society, non-government organisations, international organisations, the private sector, joint military, single service military, Coalition or foreign militaries and others who may be outside of government. 16 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview 8 Complexity Give the class time to read the slide. This is a good summary of the environment we may find ourselves operating in and, since Kofi Annan made the statement, things have probably become more complex. 9 Civil-military-police is not new You may ask if any of the class were involved with these, or other, operations. What was their role? What worked well? How could the mission have been improved? How would they prepare for another deployment? This slide reminds us of what Australia has been involved in over the last 20 years. ACMC tries to capture some of the lessons learned from these operations as well as other ‘whole of government’ responses to incidents such as the disappearance of MH370 and the downing of MH17. 10 Success in crisis management This slide gives an illustration of two government agencies working together in the field. In this picture the military and civilian leaders of Operation Pakistan Assist II confer during the humanitarian response to Pakistan floods of 2010. It is also important to note the member of the Pakistan Armed Forces standing behind the Australian soldier. The needs and capabilities of the host nation are critical for success in crisis management. 11-21 Activity Ok, time to start engaging some of the grey matter! For this activity I will not speak at all, and neither will you. I will run through a series of slides and it will become clear what you need to do. I won’t take any questions as I run through the slides. At the end of the slides you’ll need to do some writing. 17 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Is everyone clear on this? (Take clarifying questions only. Don’t get bogged down. Reassure the group that the activity will become clear). Run through Slides: Show Slides 11-19 for ten seconds each (noting slide 12 needs several clicks to build) - Show Slide 20 for 30 seconds, then move to Slide 21 and give the class about four to five minutes to write their responses. - After four to five minutes, ask several participants to each give one of their responses. This should draw out a range of issues and perspectives that demonstrate that there are many different concerns and questions to be addressed when responding to a crisis. Do not try to resolve any contentious issues; just note them as being indicative of how things often are in a real situation. After a few minutes, close the session, and explain: This is exactly what the leader of the Christchurch earthquake response, New Zealand Police Assistant Commissioner Dave Cliff, was faced with within minutes of the 2011 earthquake that razed the city centre. This was the largest natural disaster that New Zealand has faced as a nation. As he flew from Wellington to Christchurch, the 45 minute chopper ride gave him time to get his initial questions and concerns together. By the time he landed in Christchurch he was ready to hit the ground running as the Forward Controller for the crisis. He said that those 45 minutes of isolation, out of contact with everyone, were the most important in the whole first week and were crucial to the success of the rescue and recovery operation. 22 Our region This slide shows the situation in our part of the world- tsunami and flood prone areas on the left, volcanoes in the middle of the slide, earthquakes on the right. Sooner or later we will be involved in responding to new natural disasters. We cannot ignore our geography. Our region is the most disaster prone in the world. Half of the four billion people living in Asia and the Pacific (60% of the world’s population) are directly vulnerable to storms, tsunamis, tidal surges, and sea-level rise. 18 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Build the slide with three clicks: 16 million people live in low-lying coastal areas exposed to tsunami over 200 million live within 50 kilometres of a volcano over 480 million live with high to very high earthquake risk. Those vulnerabilities mean that people living in the Asia-Pacific are four times more likely to be adversely affected by a disaster than those living in Africa and 25 times more likely than those living in Europe and North America. Such a concentration of disasters in our region creates many challenges for us as there is great variability in disaster response capability across the region. In South and South East Asia, we are a key disaster preparedness partner and assist countries prepare for and self-manage disaster responses. In Pacific island nations, the small human resource base and limited infrastructure make them particularly vulnerable and dependent upon leadership from Australia and New Zealand—and for the francophone, also on France, with whom we have a special emergency response agreement. The international community expects these three countries will lead in Pacific responses. Given the vulnerability of our own region to emergencies and disasters, and the leadership role we are expected to play, the DFAT Aid Program has developed a capacity to respond to simultaneous disasters. 23 Natural catastrophes These are the facts about what is occurring around the world. The average annual number of natural catastrophes has doubled since 1980. Volcanos and earthquakes (red bars), only a slight increase Metrological events such as tropical storms (green bars), Hydrological events such as flash floods (blue bars) and climate related events such as heatwaves (orange bars), all show significantly increased frequency of occurrence. In addition to natural catastrophes, the Asia-Pacific region is very affected by conflict, mainly intrastate conflict: Over 130 million people in Asia are affected by protracted conflicts within their borders 19 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Over half the countries in our region have experienced sub-national conflict in the past 25 years. As a result of this situation, fragility and conflict are priority issues for Australia, and 7 of our top 10 aid recipients are fragile states. 24 Language Before we can go into detail about key terms and organisational capabilities, it is necessary to raise an important enabling issue for success in crisis response. The issue is words. We all speak different organisation-specific languages and we all use words differently. Obviously, avoiding too much in-house terminology and slang helps when you are working with others! Ask the class who can explain any of the terms on the slide. Don’t get bogged down, move on quickly to the next slide. The other issue is the use of abbreviations and acronyms. A good example is POC (Protection of civilians or point of contact). 25 Language -2 This slide gives two examples of how words can be used with different meanings. For instance, transition and reconstruction have different meanings to military and civilian agencies. Military organisations regard transition as being the handover to civilian control and the end of their involvement. Civilian agencies usually regard transition as being the process of a society moving from open conflict to a more stable situation. Turning to the term ‘reconstruction’, military organisations plan and conduct reconstruction operations to return a conflict or disaster affected nation to ‘normalcy’ or pre-crisis levels of capability. Development agencies, however, focus on delivering programmes that address the affected society’s existing vulnerability to conflict or the catastrophic impacts of disasters – this is the ‘build back better’ approach. These two fundamentally different interpretations of reconstruction can lead to significant disconnects in the planning and implementation of international crisis and disaster response and recovery initiatives. 20 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview The takeaway message is to make sure you have a shared understanding of key terms with other organisations. This takes time, patience and plenty of interaction. 26 Key Terms We could spend the whole module introducing and explaining the many terms used in civil-military-police interaction, but time is limited and so we will only introduce some key terms. You will be able to find more definitions in Same Space-Different Mandates (hold up a copy of the book) or by using the links provided in your Learner Workbook. Some key terms include: Civil-military-police interaction. This is an all-encompassing term to describe relations between the range of actors involved in supporting humanitarian response, stabilisation and reconstruction in complex emergencies and disasters. International non-government organisation. This is defined by the World Bank as ‘private organisations that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interests of the poor, protect the environment, provide basic social services, or undertake community development’. They include the well known organisations World Vision, Oxfam, Caritas, etc. Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). This term is used by the Australian Defence Organisation to describe support provided to host governments and humanitarian and development agencies by a deployed force whose primary role is not the provision of humanitarian aid. The aid community uses similar terms with some differences in meaning. You will hear the term HADR used on a regular basis. Complex emergency. This term is defined by the United Nations as a humanitarian crisis in a country, region or society where there is a total or considerable breakdown of authority resulting from internal or external conflict that requires an international response. United Nations Cluster Approach. The UN, government agencies, and INGOs use the term UN Cluster Approach to improve the quality of response to international humanitarian issues. Do no harm. Humanitarian organisations must strive to “do no harm”; that is to minimize the harm they may be inadvertently doing simply by being present and providing assistance. It could result in the people they are trying to help being regarded as supporting ‘the other side’ and so being targeted. 21 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview 27 Key Terms-2 Protection of civilians (POC) refers to the responsibility of the state to protect its civilians. Peace operations happen when there is instability which leads to the state being unable or unwilling to protect civilians. In this case other nations and agencies may be engaged to improve protection of civilians. Option of last resort refers to military assets being used only when there is no other option to use civilian assets. This often takes the form of the military providing transport and security to support the delivery of aid. Humanitarian space is a much used term, but its meaning continues to evolve. The most often credited source for the introduction of the term is a former president of Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF), who used it in the early 1990s to mean ‘a space for humanitarian action where we (MSF) are free to operate’. This is not just the physical area groups work in. It also refers to principles and codes of conduct. A key concern for the aid community is that they should have access to vulnerable people without fear of attack, retribution or undue pressure. Security sector reform (SSR) is a multi-disciplinary, holistic and strategic approach to reform of the security institutions of a state. It includes, but is not limited to, armed forces and police, intelligence services, border and coast guards, oversight bodies such as the executive, legislature, key ministries and law enforcement bodies. It is particularly important in Fragile States. Even these key terms are contested, and you should all take care to build a shared understanding of these and other terms when working with people from other organisations. 28 An introduction to Australian agencies The next few slides cover some of the key points about the major Australian agencies involved in humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and complex emergencies. They are: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Australian Federal Police Australian Defence Organisation Attorney-General’s Department The private sector, including community groups and civil society. 22 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview There is a separate module that covers the roles and capabilities of these agencies in more detail. Before we start it’s important to recognise that each of these agencies is sometimes stereotyped. Facilitator may read the following two questions out as rhetorical questions or may choose to ask the class for their responses. How do you think you might be perceived by members of other organisations? Are their perceptions likely to be accurate? At times NGOs are classified as tree huggers, the military as Rambos, the police as Mr Plod, diplomats as toffee-nosed aristocrats. It is important to get beyond these stereotypes so that you can get the best out of the people you are working with. 29 How Australia responds to a disaster This slide relates to the disaster context. When a crisis occurs, this is how coordination works at the bureaucratic political level. Cabinet sets the parameters; DFAT coordinates policy processes on foreign policy and consular issues, including Australian Government responses to humanitarian and stabilisation crises. Structure and process are generally guided by the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework, overseen by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PMC). An Interdepartmental Emergency Taskforce (IDETF) chaired by DFAT, remains the primary coordinating body for any international emergency response. The IDETF is not a permanent organisation but is stood up when necessary and relates to disasters off-shore and other contingencies. Domestic disasters have a different arrangement. Whole-of-government responses are always superior to single departmental responses. DFAT has primacy for off-shore disasters, generally the States for domestic disasters, and the AGD for when a ‘domestic’ response is triggered. The Crisis Management Framework is the Australian Government framework for crisis management. However, the Australian Government response will be tailored for each situation to include relevant government and other agencies as appropriate. 23 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview This is an emerging process and the structures will progressively evolve with the continued development of a national security community. 30 Organisational roles in an international crisis Allow time to read 31 DFAT This gives an idea of the size of the Department. DFAT Aid leads Australia’s post disaster humanitarian responses. Our four biggest country programs in 2014/15 are Indonesia, PNG, Solomon Islands and Afghanistan. DFAT delivers large scale programs. For example: building or extending 2,000 schools in Indonesia, creating more than 300,000 new school places, enabling children to access quality, secular education. A key point is that DFAT doesn’t just give aid; it supports the development priorities of our partner countries. The Humanitarian Division of DFAT is responsible for coordinating the government’s response to international natural disasters and humanitarian emergencies in developing countries. It maintains a 24/7 capability that can respond to two simultaneous disasters in our region. A deployable civilian capability known as the Australian Civilian Corps (ACC) delivers rapid and effective stabilisation and recovery assistance to countries experiencing or emerging from conflict or natural disaster. The capability bridges the gap between emergency relief and long term development programs. It can deploy up to 100 people at any one time, selected from a register of 500 people. Recently, personnel have been involved in Typhoon Yolanda recovery in the Philippines, developing a livelihood strategy in Burma, governance issues in Bougainville, flood recovery in the Solomon Islands and dozens of other projects. 32 AFP The next organisation is the AFP, a statutory authority established by the Australian Federal Parliament. The key component of the AFP in our context is the International Deployment Group (IDG). The IDG undertakes overseas missions and is the only national standing deployable police capacity in the world. 24 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview About 50 members are ready to go at short notice! The important point here is that the AFP is supporting the host state. This was a key focus of our efforts in the Solomon Islands as illustrated in the photo on this slide. 33 Where the AFP is engaged Of general interest is that there are still Australian Police in Cyprus – a continuous presence since 1964! 34 ADF With a $29 billion budget and range of assets, the ADF is often a significant player in any situation. The slide shows some of the operations it has been involved in recently. 35 Strategic lift and mobility This slide is included to show what might be used in an emergency operation. The KC-30A Multi Role Tanker Transport is based on the Airbus A330 and can carry 34 tonnes of cargo, 270 passengers or 100 tonnes of fuel. It is based in Brisbane. The C130 J Hercules aircraft (top right) is employed by many countries responding to humanitarian crises. Ours are based in Richmond NSW and can use short runways. The C-17A Globemaster, based in Brisbane is the second aircraft on the right and has a payload four times that of the Hercules. The bottom photo is HMAS TOBRUK, currently (2015) in service now for a range of tasks including humanitarian operations. HMAS CANBERRA commissioned in 2014 is a Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) amphibious vessel and is the largest vessel ever to serve in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Her sister ship HMAS ADELAIDE will be in service in 2016. These vessels will greatly expand the ADF ability to project forces and assist in humanitarian operations. They can carry up to 110 vehicles and 1600 personnel and have smaller landing craft to allow the transfer of people and goods. HMAS Choules and Australian Defence Vessel Ocean Shield are also large vessels suitable for humanitarian or disaster work. The ADF can meet a range of capability options across broad roles including: search and rescue, explosive ordinance, domestic counter- 25 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview terrorism, airspace control, intelligence, surveillance, medical and engineering and evacuation of Australian and other ‘approved’ foreign nationals from countries overseas. Furthermore, in an emerging security situation, enabling capabilities may be used pre-emptively, e.g. military diplomacy. 36 How non-military agencies may view the military Allow time for class to read the slide. Ask the class this question: ‘What are some of the ways to overcome these negative perceptions?’ Ask the class for their ideas. Answers. Possible responses may include: 37 Develop understanding across civil-military divide. Secondments and engagement pre-deployment may be useful, as are training and exercising together. There is also value in roundtables where people from all sides listen to each other. These actions assist in developing a culture of trust and respect. Build relations at a personal level between individuals from different organisation. Ask local communities: ‘what can we do?’, ‘What are your priorities?’, ‘How can we help?’ Ask advice of non-military agencies on specialist matters and consider how best to structure a response, as opposed to defaulting to requests for military assistance from the outset. Attorney-General’s Department The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) is the lead department within the Australian Government with responsibility for Commonwealth emergency management, national security and protective security policy and co-ordination within Australia, including: Long-term planning and policy development for emergency management, disaster resilience and security Defining and developing capability for all hazards including counterterrorism and emergency management issues Coordinating national security exercises, the evaluation of national security activities, and research and development 26 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Planning for and coordination of operational responses to all hazards through the Australian Government Crisis Coordination Centre, and Natural Disaster relief, recovery and mitigation policy and financial assistance. In the case of overseas deployments, AGD: 38 Provides legal and policy advice across Government on issues involving public international law, including the legal basis for the deployment, the domestic laws of the host state, the application of international humanitarian law where applicable, and relevant human rights norms, and Coordinates, on behalf of DFAT as the lead agency, the deployment of domestic emergency management capabilities as part of an Australian government response, in cooperation with Australian federal, state and territory government emergency management agencies. The private sector The term private sector refers to ‘for profit’ companies, community organisations and civil society. Recently, the ‘for profit’ sector has had an expanding involvement in complex emergencies, security space, logistics, advisory roles - and increasingly takes on humanitarian, aid and development tasks, as outlined by Foreign Minister Julie Bishop while describing Australia’s revised Aid Program in 2014. The private sector has become increasingly active and widespread in international disaster response and complex emergencies. There are a number of different segments of the private sector involved in humanitarian action. It is likely that the private sector will enhance humanitarian efforts across both disaster and complex emergencies in the future. Understanding and accepting the commercial realities of the private sector is essential to working effectively together. Management contractors in receipt of funding from government bodies and other ‘for profit’ entities are often used to implement donor programs in developing countries. The general principles applicable to other civil-military-police interactions apply when working with the private sector. Developing contacts and networking is also important. 27 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview A 2015 example is the Australian Government contract with Aspen Medical for the provision of Ebola assistance to West Africa. 39 An introduction to international agencies In this section we cover: International non-government organisations (NGO) The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Please note there is a separate module on these organisations that goes into more detail. 40 International non-government organisations Allow time to read There are a lot of international NGOs and many have large budgets. In addition to their own fundraising efforts, often their budgets are supplemented by contributions from national governments. The distinction between secular and faith-based organisations important because it affects their aims, methods and capacity. is Some international NGO operate across the globe while others restrict themselves to a single country. Other international NGOs focus on the needs of a particular nation or region where others have a thematic focus, for instance on children or women. Activity Ask this question: There are 5 mega international NGOs – can you name any? Answer: Oxfam, World Vision, Caritas, Care, Medecins sans Frontieres (MSF). 41 Humanitarian principles The key principles that nearly all NGOs try to adhere to are known as the Humanitarian Principles. Humanity - humankind shall be treated humanely in all circumstances by saving lives and alleviating suffering, while 28 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview 42 ensuring respect for the individual. This is the fundamental principle of humanitarian response. Impartiality - Provision of humanitarian assistance must be impartial and not based on nationality, race, religion, or political point of view. It must be based on need alone. For most nongovernmental humanitarian agencies, the principle of impartiality is unambiguous even if it is sometimes difficult to apply, especially in rapidly changing situations. Neutrality - This principle is widely used within the humanitarian community, usually to mean the provision of humanitarian aid in an impartial and independent manner, based on need alone. Operational Independence - Humanitarian agencies must formulate and implement their own policies independently of government policies or actions. Challenges to this principle may arise because NGOs rely to varying degrees on government donations. ICRC Allow time to read the slide. Most importantly, the ICRC is not an NGO, but is a unique and separate organisation. It has a special status because of its long history, having been founded in 1863 - well before many of the world’s existing international organisations, such as the UN, were established. The ICRC should not to be confused with national organisations such as the Australian Red Cross, which have a domestic focus. 43 OCHA OCHA is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures there is a framework within which each actor can contribute to the overall response effort. OCHA's mission is to: Mobilise and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors in order to alleviate human suffering in disasters and emergencies Advocate the rights of people in need Promote preparedness and prevention Facilitate sustainable solutions. 29 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview 44 OCHA global presence OCHA is a small organisation compared to the other UN agencies, funds and programs and major international NGOs that it works with. The OCHA Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (ROAP) is located in Bangkok. It provides support to 36 countries in Southeast Asia. The OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) is based in Fiji. It supports 14 Pacific Island countries under the leadership of two UN RCs in Fiji and Samoa. OCHA ROAP maintains Country Offices in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Indonesia, and the Philippines, providing support to the Humanitarian Coordinators and the Host Nations (HN). OCHA also maintains local Humanitarian Advisory Teams (HAT) in support of Resident and Humanitarian Coordinators in Nepal, Bangladesh and Japan. OCHA’s work in Asia and the Pacific is focused around three key areas: Emergency preparedness. The emphasis of OCHA is moving towards strengthening partnerships for improved humanitarian response at the country and regional levels, and supporting governments and regional organisations in their response-preparedness efforts. Since 2013, OCHA has developed a more systematic and holistic approach to response preparedness. This is aimed at helping Humanitarian Country Teams (HCT) and governments to deliver in eight critical areas of response. Emergency response. The Asia-Pacific region suffers nearly 45% of all the world’s natural disasters. Therefore, disaster response remains central to OCHA’s activities in the region. OCHA has deployed, on average, seven times per year in response to requests for international assistance from 2005-2013. OCHA’s new procedures for surge response will see the organization deploy strong and diverse teams immediately after an actual or suspected major sudden-onset disaster, based on an agreed standard team composition. Partnerships. The OCHA ROAP puts considerable emphasis on enhancing partnerships with regional, national and nongovernmental actors across the Asia-Pacific region. The aim of these partnerships is to strengthen cooperation for regional and country-level preparedness, and to ensure the understanding and 30 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview complementarity of the international humanitarian system with national and regional mechanisms. 45 OCHA functions OCHA has five core functions: Coordination, Policy Development, Advocacy, Information Management and Humanitarian Financing. Coordination. OCHA is responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. The aim is to assist people when they most need relief or protection. A key pillar of the OCHA mandate is to “coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors”. An important component of OCHA’s coordination function is related to humanitarian civil-military coordination. When an emergency or natural disaster creates humanitarian needs, many countries will deploy their militaries or paramilitary organizations to respond. Bilateral support to disaster-affected States can also be provided through international deployment of foreign military actors and assets. When local and international humanitarian organisations are also involved in that response, it is essential that they can operate in the same space without detriment to the civilian character of humanitarian assistance. It is for this reason that United Nations Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination (UN-CMCoord) facilitates dialogue and interaction between civilian and military actors, essential to protect and promote humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency and, when appropriate, pursue common goals. Policy Development. OCHA’s policy work promotes normative standards for humanitarian work and addresses a range of challenges and contexts. To most effectively align resources and relief efforts with people’s needs, humanitarian policy is increasingly based on evidence gathered at every stage of an operation, such as the Pakistan flood crisis in 2010. Advocacy. OCHA has a unique mandate to speak out on behalf of the people worst affected by humanitarian situations. To OCHA, advocacy means communicating the right messages to the right people at the right time. These people include humanitarian agencies, NGOs, communitybased organisations, national governments, local and international media, parties to conflict, companies, donors, regional bodies, communities affected by emergencies and the general public. The aim of this approach 31 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview is to shape and influence interlocutors to the situation, circumstances and particular requirements. Information Management. When an emergency occurs, OCHA information management officers immediately start working with key partners to produce standard information products to support coordination of all the humanitarian organisations and the response operation. These include the ‘Who, What, Where’ (3W) database, contact lists and meeting schedules. Tools such as the information needs assessment and maps are made available to support better relief planning and action. Humanitarian Financing. Following a humanitarian crisis, humanitarian actors in the field can immediately provide life-saving assistance using OCHA managed pooled funds. There are three types of pooled funds: the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), Common Humanitarian Funds (CHF) and Emergency Response Funds (ERF). While the CERF can cover all countries affected by an emergency, the CHF and ERF are countrybased pooled funds that respond to specific humanitarian situations. In 2014, these CHF and ERF operated in 18 countries. 46 Civil-military-police interaction at work This section introduces some of the factors that influence how things work in the field and the challenges that they present. 47 Civil-military-police actors We saw this slide earlier in the module. It is repeated as a reminder of some of the players in the civil–military-police space you may come across in an operation and gives a visual representation of the complex structures that you will have to work with. Every crisis will have different combinations of actors and management structures. 48 Civil-military-police relations…cooperate or coexist? This chart shows that the scope for civil-military cooperation decreases as the intensity of the military operation increases towards combat. Where there is combat, as shown at the right hand side of the chart, often the highest level of interaction that can be achieved is coexistence, focusing on minimising competition and deconflicting. At the left hand side of the chart, where there is peace, a much greater level of interaction may be achieved. This is called cooperation. Putting in place the actions and arrangements listed in the left hand column will 32 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the combined efforts of all agencies both civil and military. 49 Civil-military-police interaction concepts In an operational setting, it is important to understand these concepts to ensure alignment of effort. Even at the most basic level we are challenged with different methods, interpretations and terminology. Different organisations have different emphases too. These concepts are used by the military. Read out the definitions of CIMIC and CMO on the slide. Make the point that they are Australian military definitions. If the class wants more detail refer them to: More information on these terms is publically available in the Australian Defence Doctrine Publication 3.11. http://www.defence.gov.au/adfwc/Documents/DoctrineLibrary/ADD P/ADDP3.11-Civil-MilitaryOperations.pdf 50 UN civil-military-police interaction concepts The UN has a key role in many of the operations we will be involved in. This slide shows two key terms used by the UN. Read out the definitions of UN-CIMIC and CMCOORD on the slide. 51 Planning In this section we look at different styles of planning and factors that influence a complex environment. Move quickly to the next slide. 33 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview 52 Planning - Afghanistan stability diagram This is a real slide from Afghanistan showing the extraordinary level of interaction that needs to be understood when planning for a crisis or complex emergency. The slide was developed in 2009 and attempts to illustrate the groups and agencies involved in the counter-insurgency (COIN) operations in Afghanistan at that time. The chart identifies groups and the relationships between different agencies. The chart is also colour coded to identify different types of groups. For instance red is for the insurgents, green is for the population of Afghanistan, dark blue is the Afghan Security Forces, light blue is the Afghan government, including tribal governance, and black identifies Coalition agencies. The challenge presented by this level of complexity to those agencies involved in Afghanistan or COIN operations in general, is obvious. 53 How Australia responds - chart We have seen this slide earlier but it is worth a reminder of how the planning is organised in Australia. We have also looked at capabilities of the key departments involved. With this background, let’s look at some planning issues. Move quickly to next slide. 54 Planning – military versus civilian Allow time to read the slide. It is useful to understand this slide from the bottom upwards. The military are looking to ‘return to normal’ whereas civilian agencies are often looking to ‘build back better’. That means that the military has a shorter term interest than civilian agencies. Another key point is that military planning is centralised and hierarchical, whereas civilian planning tends to be less so. Another issue is that in general, the military have fully developed and comprehensive planning systems and processes, and its people are highly trained in their use. Often other organisations do not have the resources or the predisposition to match the military. 34 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview It is vital to note that none of this means that military planning is inherently superior, or that non-military agencies cannot, or do not plan. Rather, it merely demonstrates that military planning is fit for purpose for the military’s aims. Other organisations have planning styles that fit their purpose and aims. 55 The risks of planning in isolation Allow time to read the slide. Each of these actions was probably done with good intent. However the problematic outcomes could have been avoided if there had been some sharing of information to better inform planning. Question Can anyone share with the class a similar experience? Take responses from the class. 56 Planning principles Allow time to read the slide. Most people involved in an operation are there with the best of intent. We don’t all need to be the same, but we do need to accept the validity of other agencies’ styles and points of view. As always, develop networks and relationships. 57 Planning in a complex environment – key points Allow time to read the slide. We need to accept that each organisation will have a different chain of command and approach to planning - some very rigid, others quite decentralised. Remember, the considerations. host nation has to be included in all planning Agencies do not need to adopt the same language or planning processes, rather a mutual understanding of, and respect for, agency approaches is required. Collaborative planning between military and civilian agencies is essential at all levels. Effective multi-agency crisis management requires a ‘unity of effort’ rather than military style ‘unity of command’. 35 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview It is important to focus on monitoring interoperable deployable capabilities. 58 quality than maintaining Conclusion The last few slides will outline the main takeaway points from this session, including best practice ideas, principles and some additional resources from the Australian Civil-Military Centre. 59 Challenges Allow time to read the slide. The reality of these challenges means that all agencies need to make clear and continual efforts to achieve a high level of civil-military-police interaction, especially where a whole of government response is required in a very tight timeframe. 60 Success Factors This slide shows some factors that need to be in place to promote success. Allow time to read the slide. 61 Practical steps This slide gives some practical tips that you should keep in mind whenever you are dealing with other agencies. Allow time to read the slide. 62 The importance of civilian and military partnerships Allow time to read the slide. We have spent a lot of time talking about structures and processes, but when all is said and done, your success will be underpinned by being a good listener, showing respect, and conscientiously building trust. This applies to other Australian agencies, other nations and the host nation. 63 ACMC support The ACMC mission is to ‘support the development of national civil-military capabilities to prevent, prepare for, and respond more effectively to conflicts and disasters overseas.’ 36 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview In addition to preparing these awareness modules, the ACMC provides a range of material to support its mission. We will conclude the session using some of this material. 64 Guiding principles Working with its stakeholder agencies, including DFAT, AFP and Defence, ACMC has developed some guiding principles for Australian civil-militarypolice interaction. The guiding principles are represented on this diagram. It shows at the centre of the target the overall objective, which is to achieve effective outcomes. As we move out from the centre of the target, we see a light blue ring that shows the guiding principles that assist in achieving effective outcomes. The next ring is mid-grey. It identifies the key Federal government agencies that should usually be involved. The outer section is light grey. It shows the other players that you can expect to be involved. Let’s look in the light blue section, at the principles themselves. Starting at the top we see ‘Clearly Define Strategic Objectives’. Once this is done, you should ensure alignment between strategic and operational objectives. Moving clockwise, the next principle is ‘Share knowledge and understanding’. This should occur across institutional boundaries to clarify how organisations are distinguished from one another, where they have similarities and/or complementarities and what guides their engagement with others. Looking at the bottom of the light blue section we see ‘Engage proactively’. This should be done through building networks and contacts between individuals and organisations across all levels. It also invites investment in general preparedness education, training and exercises. On the left of the light blue section you will see ‘Leverage organisational diversity’. This should be done by valuing the unique cultures, technical and professional expertise, values and perceptions of organisations and individuals. 37 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview The final principle is ‘Commit to continuous improvement’. This should be done by monitoring, analysis and constant review of outcomes. 65-66 In the field…Civil-military-police checklist The next two slides provide a useful checklist. This draws together the different threads of the whole module and can be used as a reference in the future. Allow time to read 67 Same Space-Different Mandates Hold up a copy of SSDM. ‘Same Space–Different Mandates’ was designed as a field guide. It is a joint publication between ACMC and the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID). ACFID is the peak body for Australian NGOs. Same Space-Different Mandates outlines the challenges in civil-militarypolice interaction. It lists the role and capabilities of key stakeholders. It explains key concepts and processes in responding to international natural disasters and complex emergencies. It also includes a glossary of commonly used terms and acronyms, as well as military and police ranks and badges. Keep one on your desk and stick it in your backpack when you deploy. Electronic copies are available at the ACMC website. 68 Reflection I’m sure that throughout this presentation you have learned a thing or two. The whole point of the module is to improve working relationships, based on improved knowledge and understanding of each other’s roles and capability. Take a few minutes to reflect on this question – “how can I improve my ability to work with other agencies in response to conflicts or natural disasters overseas?” Jot down how the things you have learned today can be applied in your current or future role. Be ready to share some of your responses with the rest of the class. 38 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview Facilitator asks for volunteers to share parts of their answer where they are comfortable to do so. 69 Questions Take questions from the class. Answer if you can. If not, ask the class if anyone knows the answer. Otherwise your options include: Suggest the participant chases it up on return to work, Offer to find out and let the class know, or Refer the question to the ACMC. You may also wish to remind the class what you said at the outset of the session that they should expect to leave the session with more questions than when they started. You may also wish to say that the reality of civil-military-police interaction is that there will always be questions and uncertainty. As a result participants will need to develop their own strategies to get answers. 70 Farewell slide As I said at the start of this session, you should now have more questions than before. I encourage you to keep learning about civil-military-police interaction. It is a vital part of Australia’s engagement with our region and beyond. The principles and processes continue to evolve to meet unpredictable circumstances. A good illustration of this unpredictability occurred in 2014 with the loss of Malaysian Flights 370 and 17. The responses to each of these events were unprecedented and required Australian agencies to work together on unfamiliar tasks with new partners. Don’t forget that the people you’ve shared this module with may well be helpful in future, either as sources of information, providing access to their networks, or as colleagues in future operations. Give participants an opportunity to share email addresses and other points of contact if they wish. You may wish to invite participants to attend other training activities within your agency. You may choose to be available to participants for any follow up questions that they may have after the session. 39 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview If you have prepared an evaluation sheet, or using the one supplied in your pack, hand it out now and ask participants to complete it before they depart. Collect the evaluation sheets before you depart. Thanks for coming. 40 ACMC Civil-Military-Police Interaction Overview