Venture Capital and the contribution to IPO

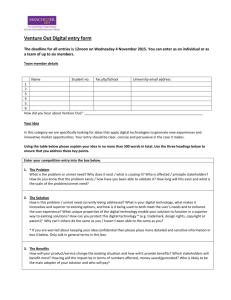

advertisement

Rotterdam School of Economics, Erasmus University International Bachelor Economics and Business Economics Bachelor Thesis 2010 – 2011 Does Venture Capital Contribute to the Success of Startups? A Literature Review July, 2011 Coordinator Italo Colantone By Georgi Nikolaev Filipov George_vtbg@yahoo.com 314992 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Venture Capital and the startups .................................................................................................................. 5 History of VC ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Invest in young firms ................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Venture capital and the growth of Startups ............................................................................................. 7 Venture Capital and Innovation ................................................................................................................ 9 Venture Capital and the contribution to IPO .......................................................................................... 11 Public Policies.............................................................................................................................................. 11 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 15 References .................................................................................................................................................. 17 2 Introduction Venture capital provides startup companies a long-term, committed share capital, in order to help them develop and succeed. If an entrepreneur needs not only a financial aid, but also someone to turnaround or revitalize the company, venture capital could help solving this. Obtaining venture capital is significantly different from raising debt or taking a loan from a bank. Banks have the legal right to interest on a loan, irrespective of the success or failure of a business. The investment that Venture Capitalists do is compensated in exchange for certain share of the business and therefore the interest that they receive is based on the growth and profitability of the company. Finally the return is generated when the share of the new businesses is sold to another owner. In a wide variety of articles it is suggested that VC’s role in a company extends way beyond the traditional financial aspect, based on their expertise in different areas they are deeply associated with the management of the firms they finance. Gorman and Sahlman (1989) observe that, on average, venture capitalists invest more than 100 hours per year in consultant activity for each company. Even Hellmann and Puri (2002) examine the influence of venture capital on the development rate of new businesses, and underline the important job venture capital has on creating expertise and competence in the internal organization of the firm. Their results imply that venture capitalists maintain new businesses to build up their human resources within the company. Fulghieri and Sevilir (2003) develop a theory of the organization and financing of innovation activities, in which the decision of organization and financial structure of R&D plays a strategic role. In particular, they show that independent venture capital financing is more likely to emerge when: R&D projects have high research intensity, when competition in the R&D is less severe or the R&D cycle involves early-stage research, and when the research unit is not financially constrained. 3 Jain and Kini (1995) show that funded companies that have been listed on a stock exchange experience greater growth in cash flows and sales. Lerner (1999) studies this topic in depth, taking into consideration Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), an important American initiative to support high-tech firms. Looking at the success of firms over the long period, for the whole sample, he finds that occupation and sales growth rates are higher for SBIR funded firms than non-SBIR funded firms for the entire period between 1983 and 1995. Further more Megginson and Weiss (1991), Tykvova (2003) provide support for the certification hypothesis and the role venture capitalists play in a firm’s IPO performance. The articles confirm that the monitoring support venture capitalist provide is fundamental for the investments they choose. So, according to the certification hypothesis, venture capitalists obtain a major equity positions, protect their investments and serve in the board of their portfolio companies. The purpose of this paper is to review the existing literature on the relationship between venture capital and the success of startup firms. In order to do so we have concentrate our research on three main characteristics of startup firms that we considered most distinctive for their success: Firm’s growth, Innovation and Initial firm’s offerings (IPOs). We believe that after examining the already existing literature on topics we will be able to distinguish if there can be significant pattern between VC and success of startups. The paper will continue with the history of venture capital and the emergence of venture capital funding. Section three is concerned with the analyses on the literature review and the 3 main characteristics that we distinguished. Section four will draw some suggestions on future policy implementations and in section five we will summarize our conclusions. 4 Venture Capital and the startups In this section the institutional details of venture capital organizations are briefly reviewed. The discussion highlights the structure and function of venture capital organizations and how venture capital is a distinct form of financing, separate from all other ways of generating funds, for young, entrepreneurial companies. History of VC According to Kortum and Lerner (1998) the venture capital industry in the United States gives its birth back in 1946, with the creation of the first venture fun, American Research and Development. In the years between 1946 and 1977 a handful of venture funds were established following the revolutionary new fund. Although the money flows back then was no more than a few hundred million dollars annually and normally even lower. An important factor that transformed the direction of classical venture investments was the change in the “Prudent man” rule after 1979. Prior to that year pension funds had a limited rights to invest significant amounts of money in venture capital by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. The major impact that this amendment had can be observed from the figures we have in the years preceding and following to the correction in the rule. In 1978 when $424 million was invested in new venture capital, only 15 percent of the money was supplied by pension funds. However eight years later the amount invested in venture capital accounted to $4 billion and more than half of it was accumulated by pension funds. In the years 1996 and 1997, there was another significant leap in venture capital activity. 5 Invest in young firms Many start-up firms require substantial capital initially in order to set up the business. A firm’s founder may not have sufficient funds to finance the planned projects alone at the beginning and will most probably seek for external ways of financing. Entrepreneurial firms lacked the possibility to obtain bank loans or other debt financing, because they were characterized by large intangible assets, highly uncertain annual earnings and low survival rates. A high percentage of these young companies had the potential to grow fast and out-pay their investments, but due to their asymmetric information venture capital was the only potential source of financing. Venture capitalist role was to provide those high-risk companies with a financial support and in return they would receive equity stakes while the firms are still privately held. Firms such as Apple Computer, Cisco Systems, Genentech, Intel, Microsoft, Netscape, and Sun Microsystems were initially financed by venture capital organizations. The financial projects that venture capitalist get involved with differ significantly from those undertake by corporate research laboratories. Applying different kind of mechanisms, venture capitalists may finance a large portfolio of projects with a high degree of risk and at an early stage with no tangible assets. An entrepreneurial venture is not restricted to a technologically based firm, a commercialization of an invention which results from R&D or an innovative cost reducing process. The appliance of already existing technologies, a product or service innovation or simply a new way of operating a business can also be considered as an entrepreneurial activity.(R. Amit 1990). The venture capitalist’s willingness to get involved in a project is most likely made conditional on the identification of a syndication partner who agrees on the investment’s attractiveness (Kortum 1998). Sahlman (1988) shows that staged financing solves agency conflicts between the venture capitalist and the entrepreneur because in contrast to the case when all the needed venture capital is provided in once now the entrepreneur has a stronger incentive to create value. The company progressively decreases its level of risk as it develops, and venture capitalist will receive a proportionately smaller incremental equity 6 position for a given amount of investment at each successive stage. According to Martin Kenney (2002) the use of equity investment rather than debt eliminates the problem of scheduled repayment. It allows young companies to reinvest their earnings and provides an asset base which can be used to attract external capital and improve a company’s credibility with vendors and financial institutions. Equity financing enables venture capitalists to undertake substantial investment risks since one enormously successful investment can more than offset a series of break-even investments or outright losses. Literature Review Venture capital and the growth of Startups Young, innovative and rapidly growing firms have to invest a substantial amount in resources before they can obtain a viable market position. However, the start-up’s equity position is very weak, and debt financing is often restricted by certain country specific or sector specific regulations. According to Dirk Engel (2002) Venture capitalists take a major role in closing this gap by providing the financial support. Moreover those investors often contribute not only with the funding of such firms, but also with the implication of a monitoring control and strategic management expertise in the early stage. Both types of support indicate a positive impact on growth rates of the venture-backed firms. The role of venture capitalists offers some favorable conditions for the growth of venture-backed firms. In a vast amount of recent studies venture-backed firms are compared to those that have obtained no venture capital at all and perform in similar sectors in order to examine the influence of VC on the tendency to grow. Whether access to VC financing actually spurs the growth of investee companies is a matter of empirical testing. For example, Alemany and Marti (2005) compare the population of the 323 Spanish firms that obtained VC financing in the period 19931998 with a control taste of similar but non VC-backed companies. Matching is based on the region in which firms are located, sector of activity, age and size in the year in which VC 7 financing was obtained. The researchers believe firms’ sales, employment and total assets; and calculate average growth from the “event” year up to the third year after the event, making a distinction according to the stage of the investee company’s life (i.e. start-up, growth, mature) in which VC financing was obtained. VC-backed companies are found to outperform their non VC-backed counterparts if VC investment takes place in the start-up or growth stage. Massimo G. Colombo and Luca Grilli (2005) analyze the effect of VC financing on the growth of sales and employment of startup firms in subsequent years. For this purpose, they examine a sample of 537 new Italian firms for the period 1993- 2003. The purpose is to evaluate what is the impact of VC on the firm’s subsequent growth and whether the degree of this effect varies according to the nature of the investors (specialized venture capital or corporate venture capital).Estimates reveal that venture capital financing has a significantly positive effect on the development of startups. The marginal increase in the number of the firm's employees is decreasing over time, indicating that VC has a higher impact on the firm’s growth in the first years following the financing. Manigart and Hyfte (1999) find that the rate of growth of total assets of a sample composed of 187 Belgian VC-backed firms is significantly greater than that of the control sample in each year starting in the year in which the firm obtained VC financing and for the following five years. Lastly, the growth rate of employment is greater in the VC-backed sample only when one considers star performers that are the firms that belong to the percentiles with the greatest growth, and a sufficiently long period (at least three years after the investment). Moreover, Engel and Keilbach (2002) analyze the impact of venture capital investment on growth and innovation of 142 young German firms. To test their hypotheses they use the nearest neighbor criterion with an additional requirement that the firms have to operate in the same industry and to be established in the same year as the venture baked firms. Based on this method they found evidence that venture-funded firms exhibit significantly higher growth rates compared to their non-venture-funded counterparts, thus venture capital firms make a significant contribution in this respect. 8 Other studies like (Gorman and Sahlman 1989, Bygrave and Timmons 1992, Sapienza 1992, Kaplan and Strömberg 2004) focus on the fact that VCs perform a significant coaching function to the benefit of investee firms. They provide portfolio companies with consulting services in fields such as strategic management, marketing communication, finance and human resource management, where these firms typically lack internal capabilities. For instance, Hellman (2002) proves that VCs support the engagement of external managers, the implementation of investments plans or participation in the HR polices of the invested firms, thus reflecting in the company’s managerial expertise and growth. Moreover, venture-baked firms can contribute from the already established networks of their investors such as suppliers, prospective clients, partners or alliances. Venture Capital and Innovation According to R. and Kenney,M. (1988) venture capitalist are well known for two core activities: providing funds and assisting in the emergence of new high technology businesses. They actively cultivate networks comprised of financial institutions, universities, large corporation’s entrepreneurial firms and other organizations. These networks and the data flow at their disposal let them reduce many of the risks associated with new venture formation and thus go easier through the barriers innovation cycle can have. Venture capital-financed innovation is a “new model” of innovation which goes beyond both traditional entrepreneurship and corporatebased innovation. Kotrum and Lener test the possibility that venture capital and patenting may not be the only factors that affect innovation and suggest that entrepreneurial opportunities is an unobserved variable which can also be positively correlated to innovation. They try to reach the reasons about causality by explaining two different factors. First, they observe the amendment in the “Prudent Man” rule made after 1979 by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and the 9 followed discontinuity effect in the total investments. As discussed earlier in the paper the change allowed pension funds to invest in venture capital industry which lead to a substantial increase in the money flow. They argue that such an exogenous change should confirm the significance of venture capital as an instrument to boast innovation, because it is irrelevant to be connected to the appearance of entrepreneurial activity. Second, they examine R&D expenditures to test for the occurrence of technological opportunities that were expected during that time, but were not taken into account by econometricians. They use a simple model framework to prove that the causality effect evaporates if we asses the impact that venture capital has on patent R&D ratio, rather than on patenting itself. Although these causality problems have been observed, findings still support the major importance of venture capital on innovation. The results obtained through different models imply that an investment made by venture capital fund can be up to ten times more valuable to patent creation, compared to a traditional corporate R&D investment. Moreover, they estimate that regardless of the fact that venture capital was in total 3% less than corporate R&D in the last years, it contributed with 15% more to the U.S industrial innovations. Hellmann and Puri (2000) use a different way to show that venture capital leads to more innovation. They suggest that higher levels on innovation are caused not just by venture capital in general, but rather because venture capitalist have the incentive to respond on important technological opportunities which are likely to lead to more innovation. In their observations they use a sample of 170 recently formed firms, comparing venture-backed to nonventure firms. After performing a questionnaire survey, they advocate that venture capitalist are not only involved in the financing, but are also associated with the marketing strategies and outcomes of the firms. Moreover startups that position innovation as an underlying strategy in their work obtain venture capital significantly faster. They find a straight correlation between venture capital presence in a firm and the time needed to promote a product to the market. In addition, firms are more likely to mark involvement of venture capital in their business, as the most vital point in their development, compared to other financial inflows. The results indicate 10 significant interrelations between investor category and product market dimensions, and a function of venture capital in encouraging innovative companies. Knowing the relatively small sample of firms and the scars data available, just a moderate concerns about the causality can be done. Unfortunately, we can not reject probability that innovative startups prefer venture capital for financial reasons, rather than VC to create innovations. Caselli, Gatti and Perrini perform another research on whether venture capital spurs innovation inside funded firms by analyzing the number of registered patents before and after funding. They analyze 37 Italian venture baked firms and by a matching way they choose 37 twin non-venture backed firms. However the results differ significantly from the literature cited above. Before funding, funded firms show 0.3327 more patents than non-funded firms do per year, on average; after funding, they report 0.53825 fewer patents than their twins do per year, on average. The propensity to innovate seems an essential requirement for passing the screening phase of the venture capitalists’ selection process, but on the other hand, the entry of venture capital into the company does not promote continued innovation. Venture Capital and the contribution to IPO Venture capitalists are similar to leveraged-buyout (LBO) specialists, who seem to contribute to significant improvements in performance in corporations that go private. Like LB0 specialists, venture-capital providers are involved in financing and monitoring their portfolio companies. LB0 specialists and venture capitalists invest in different kinds of firms, however: LB0 promoters usually invest in mature companies with predictable cash flows, whereas venture capitalists focus on young and high-risk entrepreneurial ventures. The venturecapital market therefore provides a useful alternative setting in which to explore the role of active investors with concentrated ownership claims. The role of venture capital investment on initial public offerings has been extensively discussed in the literature. Two papers can be significantly distinguished among others: those of Megginson and Weiss (1991) and Barry, Muscarella, Peavy, and Vetsuypens (1990) as one of the first to examine more deeply the topic. Megginson and Weiss (1991) suggest that because of 11 the venture capital “certification”, IPOs of companies that are venture-backed are less under priced than non-venture backed IPOs. The term venture capital certification represents the belief that venture capitalist are concerned about their reputation, because of their repeat actions on the IPOs market. Therefore they would value the IPOs of the firms they bake more realistically and closer to the true intrinsic value of the firm. Matched by industry and offering size, indicates that VC backed firms are significantly younger, have greater median book values of assets, and a larger percentage of equity in the capital structure than their non-VC backed counterparts. In addition, VC backed firms are able to attract higher quality underwriters than non-VC backed IPOs. Barry et al (1990) also imply that same observations that venture-backed IPOs are less under priced compared to non-venture backed IPOs. Although, they argue that the difference in the pricing of IPOs is due to the fact that the capital market is aware of IPOs with better monitors. More precisely, venture capitalist fund only the top part of the firms in the market, therefore a better quality from these firms is expected. According to Bharat A. Jain and Omesh Kini (1995) the market appears to recognize the importance of monitoring by venture capitalists and the followed higher valuations at the time of the IPO. They examine the proposition by comparing the post-issue operating performance of venture backed IPOs with a matched sample of non-venture backed IPOs. The results show that the involvement of VCs speeds up the process of development and allows the company to go public earlier than it would be otherwise possible. The companies also go public with a higher valuation than would be possible otherwise, providing issuers with additional capital at the IPO. Further, in the initial stages of a public corporation, VC monitoring ads value as evidenced for improved corporate performance. From the investors’ point of view, VC participation signals quality. This should lead to increased interest in VC-backed IPOs compared to similar non-VC-backed issues. However, in more recent papers the contrary results have been documented. Lee and Wahal (2000) suggest that for the period between 1980 and 2000, venture backed companies have actually been more under priced than non-venture backed companies. Results show that VC backed IPOs exhibit greater underprice than non-VC backed IPOs. The return differential ranges from 5.0% to 10.3% over the entire sample period. During the internet bubble period of 1999– 12 2000, the differential is significantly larger. The authors interpret these results with the grandstanding hypothesis which in other words indicate a negative correlation between venture firm reputations and underprice. Since establishing reputation is so important for future fund raising, venture capital firms are willing to bear the cost of underprice because taking a company public signals quality. Reopening the debate about the role of VC in IPOs Thomas J. Chemmanur and Elena Loutskina (2006) approach the debate from a different perspective and use a different hypothesis. What they suggest is to distinguish between the hypotheses about venture funding mentioned above and include a third probable hypothesis that they refer to as “market power”. It reflects the possibility that venture capitalist can use their powerful positions on the market due to the strong relationships they build with the participants in the market. These long-term connections allow them to pull a higher participation by underwriters, institutional investors or analysts and acquire higher prices for the IPOs of their firms. Venture capitalists may be motivated to achieve higher valuations for the IPOs of firms backed by them, due to concern for reputation with their own venture fund investors and entrepreneurs. This reputation is essential for venture capitalists’ ability to raise financing for future venture funds. Results reject the certification hypothesis and provide significant support for the market power hypothesis. We find that venture backed IPOs are much more overvalued than non-venture backed IPOs and that high-reputation VC backed IPOs are more overvalued than low-reputation VC backed IPOs, both at the bid price and at the closing of the first trading day. The difference in valuation between venture backed and non-venture backed IPOs (and between high-reputation and poor reputation VC backed IPOs) becomes larger at the start of trading in the secondary market, but dissipates over time, almost disappearing at the end of the third year after the IPO. Public Policies As already mentioned in the above literature review the impact of venture capital on innovation is likely to differ with the venture capital cycle. Yet government policies have often 13 been focused to provide support during periods when venture capital industry is most active and also targeting sectors in the business that have already been strongly funded by venture capitalist. A successful approach would be to address the gaps in the venture financing process. Investments made by venture capitalist tend to be centered in mainly in technology areas that are already supposed to have a high potential. The tools that have been used till now to increase venture fund raising, such as shifts in the capital gain tax rates, seemed to focus the competition in one sector rather than diversify the firms that receive funding. Policymakers should try to react on these conditions by (i) drawing the attention on technological opportunities that are still not explored by venture funds and (ii) providing support to companies that have been financed by venture capitalist but are in a down period. More generally, one of the best possible solutions for government polices to provide assistance may be to increase the demand for venture capital, rather than the flow of capital. Therefore the effort to build more attractive image of entrepreneurship activity through tax policy, may result in a significantly positive way to the amount of venture capital investments and the returns they yield. The less direct action can contribute the most for the survival of the venture capital industry. The analyzes on the growth of venture-baked firms showed that venture capital can without any doubt foster the growth of startups. An important policy issue obviously is whether VC baked startup investment can be influenced more directly by means of taxes or subsides. Indeed most countries offer many programs to assist startup entrepreneurship, and part of it is explicitly directed towards the VC industry. Most of these programs subsidize the cost of capital by means of credit guarantees to facilitate bank finance at a lower interest rate. These subsidies have in common that they are not performance related. Since these firms do not generate revenue during the startup phase, the return to entrepreneurs and investors mainly consists of capital gains. For this reason policy makers often propose to reduce the capital gain taxes. 14 Conclusion This paper has examined the contribution of venture capitalist to the success of startups. For this purpose it was performed a literature review on an extensive volume of articles associated with the effects of venture capital on entrepreneurship. We mainly focused our observation on three key characteristics of the success for startups which we distinguish in the beginning of the article: Firm’s growth, Innovation and Initial firm’s offerings (IPOs). Although not all of the examined studies showed a clear pattern that VC contributes to the success of startups, the wider part of the literature supports the assumption that VC has a main role in the future success of startups. Engel and Keilbach (2002) performed an empirical test on the impact of venture capital investment on the growth of 142 young German firms. They found evidence that venture-funded firms exhibit significantly higher growth rates compared to their non-venture-funded counterparts, thus venture capital firms make a significant contribution in this respect. Similarly Massimo G. Colombo and Luca Grilli (2005) proved the existence of a direct causality relationship between VC investment and startup's growth after observing a sample of 537 new Italian firms. Kortum and Lerner (1998) researched twenty different industries in order to determine whether VC has an impact on the patent innovations Although some causality concerns occurred, the findings support the positive impact of venture capital industry on innovation. Their estimates suggest that regardless of the fact that venture capital was in total 3% less than corporate R&D in the last years, it contributed with 15% more to the U.S industrial innovations. In addition according to Bharat A. Jain and Omesh Kini (1995) the market appears to recognize the importance of venture capitalist’s monitoring role in determining the IPOs prices. They observe causalities for this by comparing a sample of venture backed IPOs to a matched sample of non-backed IPOs. 15 Nevertheless, Thomas J. Chemmanur and Elena Loutskina (2006) use a different approach to examine the debate about venture capital and IPOs pricing. They include a third hypothesis, which they referred to as “market power”, showing the possibility that venture capitalist can use their long-term connections on the market in order to acquire higher prices for the IPOs of their firms. Results reject the certification hypothesis and provide significant support for the market power hypothesis. We find that venture backed IPOs are much more overvalued than nonventure backed IPOs and that high-reputation VC backed IPOs are more overvalued than lowreputation. It can be identified from the literature cited above that VC perform a crucial role in the development of startup firms. In order to summarize our research it should be mentioned that empirical evidences, concerned with all the main characteristics observed in the paper, confirmed the highly contributive function of VC to the success of startups. 16 References: 1. Stefano Caselli, Stefano Gatti and Francesco Perrini. (2009). Are Venture Capitalists a Catalyst for Innovation?. European Financial Management,. 15 (1), p92 Samuel 10. WILLIAM L. MEGGINSON and KATHLEEN A. WEISS. (July 1991). Venture Capitalist Certification in Initial Public Offerings. THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE. VOL. XLVI, (3), 2. Kortum and Josh Lerner. (Winter 2000). Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation. RAND Journal of Economics. 31 (4), pp. 674-692.–111. 3. Samuel Kortum and Josh Lerner. (December 1998). Does venture capital spur innovation . NBER Working Paper . 1 (6846), 1. 4. Josh Lerner . (2000). Negotiation, Organizations and Markets Research Papers. Harvard NOM Research Paper. 1 (03-13), 1. 5. Masayuki Hirukawa and Masako Ueda. (September 2008). Venture Capital and Innovation: Which is First. none. 6. Richard Florida and Martin Kenney . (November 1987). Venture Capital-Financed innovation and technological change in USA. none. 7. Christopher B. Barry. (August 1990). The role of venture capital in the creation of public companies. Journal of Financial Economics. 27 8. Thomas J. Chemmanur* and Elena Loutskina. (September, 2006). The Role of Venture Capital Backing in Initial Public Offerings: Certification, Screening, or Market Power. 9.Bharat A. Jain and Omesh Kini. (1995). Venture Capitalist Participation and the Post-issue Operating Performance of IPO Firms. MANAGERIAL AND DECISION ECONOMIC. 16 (1), 593-606. 17