enhancing and sustaining agricultural productivity for food and

advertisement

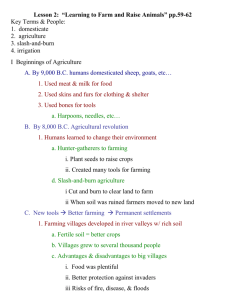

Chapter 7. Enhancing and sustaining agricultural productivity for food and nutrition security K V Peter and Binoo Bonny Despite tremendous gains in global food production, there is unusual increase in the number of undernourished in recent years with figures crossing 1 billion mark in 2009-10 with only marginal reductions there after (FAO, 2008). This mismatch was identified quite early and gave credentials to the acceptance of food security as a defining development concept in the first World Food Conference of 1974. Since then 50 years have passed and four more Food Summits were held at short intervals in 1996, 2000, 2002 and 2006 which resolved to reduce hunger to half by 2015. The major impediment remains the unprecedented increase in the rate of population growth as indicated with the current world population at 6.2 b. which is expected to cross 8.2 b. by 2020. This needs to be evaluated in the context that it took the initial 4 million years for the humanity to reach 2.5 billion in 1950. Till early 1970s it was the national and global food supplies which dominated the food security concerns of the world. The limitation of the food supply focus was quite evident in the individual and household levels of poverty standards. The theory on food entitlement by Sen (1981) and related works lead to a comprehensive conceptualization of food security as a situation when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for a healthy and active life (FAO, 2008). It entails along with availability of food, accessibility and entitlement to food as determinants of the overall household food security. It became clear that adequate food availability at the national level did not automatically translate into food security at the household level. The FAO (2010) estimates of the global trends of poverty and under nourishment as reported in Table 1 show that the number of 1 undernourished people in 2007 increased by 75 million, over and above FAO’s estimate of 848 million undernourished in 2003-05. The AsiaPacific region with 578 million undernourished and sub-Saharan Africa with 239 million hungry people account for 62 and 26 % respectively of the world’s food insecure population. More importantly, the majority of the people who cannot meet their nutritional needs depend on agriculture for livelihood. Much of this increase is attributed to the continued and drastic increase in prices of staple cereals, pulses and oil crops (Fig -1) since 2004 leading to an estimated 100 million more people pushed into poverty. Unlike earlier food price shocks which were mainly driven by short term food shortages, the 2007-08 price spikes came in a year when the world reaped a record grain crop with more than 100 million metric tons of extra grain compared to previous year. In this the relation between price volatility and hunger has been explained in terms of widening demand supply gap attributed to population growth, energy cost leading to conversion of farm lands into biofuel crops and climate variability. This brought the number of undernourished people worldwide to 925 million in 2010 (FAO 2012) and the global food demand is expected to be doubled by 2050. The first World Food Summit held in 1974 was aimed at eradicating world hunger within a decade. Unfortunately the hunger and food security statistics show that even this target is not likely to be met due to conglomeration of reasons both at lopsided policy level and occurrence of natural calamities. The manifestation of poverty in forms of calorie deprivation, protein deficiency and micronutrient deficiency is part of food security concerns. All these are encapsulated into the UN zero hunger project aimed at evolving sustainable food systems, ensuring zero wastage of food, 100% increase in small holder productivity and income, year round100% access to adequate food for all by 2025. Therefore the onus to eliminate hunger continues to rest with agriculture and its capacity to address the following inherited and future challenges. Increase food production by 70% to feed a growing population of 9.00 billion by 2050 2 Meet the dietary requirement changes linked with rising income in developing countries Sustainable management of over exploited and depleting natural resources through investments and incentives Compacting the impact of increasing food prices and energy crisis Initiatives for climate resilient agriculture Management of production from small and family farms Indian Scenario Journey of Indian Agriculture from the years of acute food crisis to food self sufficiency and food security entitlements is tremendous. From the years of Bengal rice famine of 1943 which killed over 3 million children, women and men from hunger and starvation to the National Food Security Bill of 2013, it has been posed with the challenges of population, poverty and climate change. Enormity of the problems faced by Indian agriculture is evident from the fact that despite the national gains in food self sufficiency (51million tones in 1951 to 258 million tons in 2013) and security through the heralded Green revolution, India still has a population of 250 million food insecure inhabitants which roughly estimate to one fourth of world’s food insecure people (Table 2). The Global Hunger Index (GHI), a more comprehensive tool used to measure and track global hunger, ranks India in the category of alarming poverty along with Bangladesh as evident from Table 3 (IFPRI,2008). More disturbing are the rates of malnutrition among the most vulnerable sections of Indian population like women and children (Table 4). Green Revolution Despite rampant hunger and poverty, the food production trends show an impressive record of taking the country out of serious food shortages. The annals of Green revolution which demonstrated favorable interplay of infrastructure, technology, extension, risk taking farming community and policy support backed by strong political will provided India the much needed impetus. Indian farmers achieved as much progress in 3 wheat production in four years (1964–68) of green revolution, as during the preceding 4000 years (Table 5).The main source of long-run growth was technological augmentation of yields per unit of cropped area. This resulted in tripling of food grain yields, and food grain production increased from 51 million tones in 1950–51 to 217 million tones in 2006–07. Production of oilseeds, sugarcane, and cotton have also increased more than four-fold over the period, reaching 24 million tones , 355 million tones and 23 million bales, respectively, in 2006–07. But, although GDP from agriculture has more than quadrupled, from Rs 1083740 million in 1950–51 to Rs 4859370 million in 2006–07 (both at 1999–2000 price), the increase per worker is rather modest (Fig-2). Moreover the percentage contribution of agriculture to the overall GDP also decreased from around 50 in 1950-51 to 30 in 1990-91 to 15.7 in 2008-09. In the last two decades, agricultural growth rate (3%) is around half of the overall growth rate of 6-7% (NAAS, 2009). But there has been only slight fall in the population dependent on agriculture for employment and livelihood with 61% in 1990-91 to 52% in 2008-09. The average farm size also recorded significant fall from 2.3 ha in 197071 to 1.32 ha in 200-01 with an increase in the number of small farm holdings from 70 million to 121 million during the period due to arable land conversion and fragmentation. At this trend it is projected to be 0.68 ha in 2020 and 0.32 ha by 2030. Fast growing population is one of the major factors that negated the Indian achievements in food production. Population of 520 million in 1947 has crossed the billion mark to reach 1120 million in 2013. In meeting the predicted food requirement of 345 million tons in 2030 the food production needs to be increased at the annual rate of 5.5 million tones. Moreover, there is a predicted increase of 100% in the demand for high value food products of horticulture, dairy, livestock and fish during the years 2000-2030 (Fig.3). This is attributed to the increased rural urban migration and increase in quality of life. This necessitates high investments in infrastructure and cool chain development for its handling, value addition, processing and marketing. The required growth over the base year production (2006-07) to achieve domestic demand by 4 2020 is presented in Table 6. But the production environment remains hampered by the continuously shrinking and deteriorating natural resources and impact of climate variability resulting from a continuously increasing global temperature. Around 120.72 million ha land is degraded out of agriculture due to soil erosion and 8.4 million ha is affected by soil salinity and water logging. Green house gases from agriculture are estimated to contribute 30% of global emissions causing climate change. The total amount of GHGs emitted in India is estimated at 1228 million tones, which accounted for only 3 % of the total global emissions, and of which 63 % was emitted as CO2, 33 % as CH4, and the rest 4 % as N2O. The GHG emissions in 1990, 1994 and 2000 increased from 988 to 1228 to 1484 million tones respectively and the compounded annual growth rate of these emissions between 1990 and 2000 is 4.2 % which is low compared to many developed countries. Thus agriculture in India is unfolding a new agrarian model where domestic product is low, average size of holding is contracting/ fragmenting and number of operational holdings increasing. Reduction in farm size without any alternative income augmenting opportunity is resulting in fall in farm income leading to agrarian distress. It is in this context the augmentation of food production through small farm holdings and family farms, urban and peri-urban agriculture assumes significance. Crop diversification, homestead farming and establishment of bio-fortified-nutri-farms in small holdings by integrating principles of farm ecology, nutrition and farm economics are proposed to defend the gains of food self sufficiency. Protected cultivation, biotechnology and nutraceuticals can play the critical role of supportive technology in achieving the zero hunger targets. Small and Family farms Assuming the significance of small holdings and family farms in future food production, General Assembly of the United Nations in its 66th session adopted 2014 as the “International Year of Family Farming” (IYFF). It aims at repositioning family farming at the centre of agricultural, environmental and social policies in the national agenda by 5 identifying gaps and opportunities to promote a shift towards a more equal and balanced development. It helps to raise the profile of family farming and smallholder farming by focusing world attention on its significant role in the fight for eradication of hunger and poverty, providing food security and nutrition, improving livelihoods, managing natural resources, protecting the environment, and achieving sustainable development particularly in rural areas. Family farming includes all family-based agricultural activities and is linked to several areas of rural development. It is defined as a means of organizing agriculture, forestry, fisheries, pastoral and aquaculture production managed and operated by a family and predominantly reliant on family labor. Family and small-scale farming are inextricably linked to world food security as it forms the predominant type of agriculture in both developing and developed countries. It involves around 2 billion people, almost one-third of humanity. Around 70% of the world’s food is produced on 404 million small-scale farms of less than 2 hectares operated by 1.5 billion men and women farmers. It is estimated that 4060% of rural income in developing countries is generated in these small family farms. In addition to the essential role they play in food production, they have significant contribution in sustaining rural economies and stewardship of biodiversity. Yet most of these are very poor and operate in disadvantaged conditions with insufficient access to resources and support. Expensive and short-term solutions proposed by conventional agriculture do not hold good for the social and economic problems of smallholder farmers. Many farmers are forced to purchase expensive inputs which often push them into a cycle of debt. Beyond the financial implications, these inputs also pollute the environment, destroy biodiversity and degrade the nutritional quality of our food. Therefore, organic agriculture and other agro-ecological models are suggested as the most appropriate way to achieve ecological, agronomic and socioeconomic intensification of family farming and smallholder agriculture. It also provides healthy and nutritious food. Organic farmers ensure that traditions are kept alive and facilitate marketplace success by sharing 6 experiences and developing new farming methods. Together, organic smallholders can strengthen social structures, develop innovative networks and promote entrepreneurship, the impact of which includes more job opportunities, a stronger local value chain and improved rural development. Indian Context At national level, there are a number of factors for a successful development of family farming like agro-ecological conditions and territorial characteristics; policy environment; access to markets; access to land and natural resources; access to technology and extension services; access to finance; demographic, economic and socio-cultural conditions; availability of specialized education among others. Family farming has important socio-economic, environmental and cultural role as 81% of total agricultural holdings belong to the category with an average holding size of 1.33 ha. Statistics on the farming population of the country (Table 7) indicated 49% of the farms are in the family farm category. Contribution of these farms to the national food security is enormous as 60% of the production comes from these family farms. These family farms grow traditional crops mostly following organic and natural farming practices. These practices help in the maintenance of traditional flavor of commodities, soil fertility, environment and reduction in the Green House Gases (GHG) and effects of climate change. However, incomes of Family Farm Farmers are not in tune with increase in the prices of agricultural inputs. Inadequate access to natural and basic resources for production, markets, value addition and processing are responsible for the uneconomic functioning of these farms. This has been instrumental in perpetuating poverty, hunger and malnutrition in the country and keeping these farm families in a highly disadvantaged socio-economic situation. Many food aid programs like midday school meals for school children, subsidized food grains through public distribution system and the legendary Food Security Act of 2013 which ensure legal right to food for all are operational in the country to combat 7 problems of hunger and malnutrition. In fact, the Food Security Bill addresses the problems of calorie deprivation, protein hunger and micronutrient malnutrition. It ensures legal entitlements to food through Life Cycle Approach with special attention to the first 1000 days in a child’s life, and considers women as head of the household with regard to food entitlements. It provides the right to enlarged food basket with 35 kg per family per month of wheat, rice or climate smart Nutri-cereals. These enabling provisions on food availability and food absorption are ensured through national grid of grain storages and Public Distribution System(PDS) reforms. However, these can only be considered as short term solutions against hunger and the government needs to focus more on sustainable strategies in agricultural production which target the poorest households in meeting the hunger reduction targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) (Sustainable Development Goal from 2015) and World Food Summits. Homestead farms and nutritional gardens provide great scope in overcoming widespread malnutrition prevailing in our country by enabling farm families to have balanced diet. The programe for organizing Nutri-farms will involve introducing in the cropping system, biofortified crops rich in iron, zinc, vitamin A, Vitamin B 12 and other micronutrients as well as those which are rich in protein like quality protein maize. The programe may be taken up in the districts suffering from a high burden of hidden hunger caused by micro-nutrient deficiencies. Homestead Farming Small holder homestead farming, at this juncture, has proved to be a time tested method for ensuring food sufficiency. Home gardening or homestead farming is the oldest land use activity next only to shifting cultivation evolved through generations of gradual intensification of cropping in response to increasing human pressure and the resulting shortage of arable lands The origin of home gardening could be traced to South East Asia and East Africa . In Java(Indonesia) and Kerala(India) , home gardening is a way of life and is still critical to local subsistence 8 economy and food security (Nair and Kumar, 2006). A homestead is an operational farm unit in which a number of crops (including tree crops), vegetables, fruits,spices, ornamentals, tubers and medicinal plants are grown along with livestock, poultry, and/or fish production mainly to satisfy the farmers basic need (Tejwani, 1994). A home garden could also be viewed as an integrated system which comprises different components in its small area: the family house, a living area, a kitchen garden, a mixed garden, a fish pond, stores, an animal house and, of course people. The system with a mix of vegetables, flowers and medicinal plants as intercrops in fruits and plantations involving spices was able to sustain the biodiversity of vegetation around the household with a change in the local micro-climate having long-term benefits on health of family members. However, the traditional home gardens were managed unscientifically without any planning and with very low resource use efficiency. Increasing population and low per capita availability of arable lands have necessitated the need to have better managed home gardens. Evidences from various parts showed that homestead farming and interventions in home gardens could play a significant role in improving food security especially for the resource poor rural households in developing countries. Ali et al (2008) reported that in Bangladesh, implementation of a project aiming to provide farmers a subsidiary source of income through potential homestead farming system, to increase and sustain productivity of existing homestead farms and to encourage maximum utilization of available family labor, through vegetable could meet the daily vegetable requirement of small farmers by supplying 200-220 g/head/day against the bench mark level of 40-50 g/head/day. Also vegetable intake largely provided required amount of Vitamin A, C, calcium and iron. Thus food security was increased; nutritional deficiency was reduced along with women empowerment. The home gardens of Kerala evolved in response to the pressure of a shrinking land resource base coupled with a high population density, which necessitated a conscious attempt on the part of farmers to achieve their goals by living within biophysical, ecological, and economic 9 constraints is another classical example of family farm. As a traditional farming system, home garden agriculture is essentially subsistenceoriented, with need based production and labor provided mostly by the family itself. High-density farming involving several species of seasonal, annual, and perennial crops thus evolved to meet their demands and to achieve highly efficient use of resources. To supplement the subsistence level on-farm income from smallholdings, household members are being driven to off-farm employment and the high opportunity cost of family labor has led to the development of part time farming also (Salam et al. 2000). A study conducted to determine the socioeconomic factors and constraints which affect farming in 400 homesteads of Kerala by John and Nair (1999) revealed that 17.5 % and 30.25% of the homesteads raised cattle and poultry, respectively, as a complementary enterprise. The system in general was reported profitable, resulting in a net profit of Rs 0.280million /year with a benefit:cost ratio of 2.35. Nearly 78% of the farmers reported labor scarcity, while 97.75% mentioned high labor cost to increased cultivation cost. A study by ICAR Research Complex Goa in 20 homesteads indicated that nearly two-thirds of the homestead-grown vegetables are consumed in the household with only one-fifth of the vegetables being sold in the market while a part of it is exchanged among the neighboring households. Most of the vegetable production in the homesteads was concentrated during November to March coinciding with the postmonsoon period. Nutritionally, the homestead met most of the mineral and vitamin requirement of the household family members although carbohydrates and protein requirements were met partly only by the homestead production. The project also helped to develop model homestead units for different holding sizes of the household based on the family requirement and the marketing potential keeping in view the resource situations including part or fulltime availability of the family members to work in their gardens. The Homestead Food Production (HFP) program, introduced in Bangladesh by Helen Keller International nearly two decades ago, to promote an integrated package of home 10 gardening, small livestock production and nutrition education with the aim of increasing household production, availability, and consumption of micronutrient-rich foods and improving the health and nutritional status of women and children is now operating in several countries of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Evidence shows that HFP in Bangladesh improved food security of nearly 5 million vulnerable people in diverse agro ecological zones. This was achieved through increased production and consumption of micronutrient-rich foods; increased income from gardens and less expenditure on micronutrient-rich foods; women’s empowerment; enhanced partner capacity and community development (Iannotti et al 2009). Asaduzzaman et al (2011) quantified the cost/benefit of traditional and developed homestead vegetable production systems and suggested that developed gardening has better performances in terms of calorie intake and economic performances over traditional but the optimal calorie intake with least-cost technology could be a feasible livelihood strategy for resource poor people. Developed garden contributed 10% to achieve threshold poverty level whereas traditional contributed only 2%. On the basis of input costs other than family labor, BCR was higher in developed (3.24) than traditional (2.63) but when labor cost was included in the analysis, traditional gardening was still feasible (BCR 1.25) but developed garden (BCR 0.60) appeared as non-profitable .The study concluded that developed gardening is profitable compared to traditional if the opportunity cost of family labor is ignored as an item of cost of production. Urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) UPA has evolved from a simple, traditional and informal activity into a commercial and professional initiative. It has become a key element in food security strategies officially recognized by the 15th FAO-COAG session in Rome, 1999 and at the World Food Summit, 2002. It is conceptualized as an agricultural production process located within (intra-urban) or on the fringe (peri-urban) of a town, a city or a metropolis, which grows, processes and distributes a diversity of 11 agriculture products, using largely human, land and water resources, products and services found in and around that urban area. UPA provides the urban migrants who are constrained for the very necessities of life and that too at compromised quality standards and exorbitant rates, an opportunity for self provisioning of safe and diverse food. It serves as a means for vulnerable groups to minimize their foodinsecurity problems by reducing their reliance on cash income for food by growing their own food on plots inside or outside the city, thus increasing their access to food. Furthermore UPA allows for saving on energy at various levels of food chain including packaging, transport, storage and distribution which will affect the final retail price of the food commodities. However, UPA cannot be expected to satisfy the urban demand for staple crops like cereals and tubers, but need to be appreciated as an important strategy for self-provisioning, especially for poor households. Moreover, the highly developed commercial urban farming that supplies urban residents with fresh vegetables, fruits and animal products also forms a major component of the urban food system. Thus it also helps in providing the diversity needed to ensure dietary quality – an important aspect of food security. Given the urban constraints related to land, water and other amenities needed for farming, UPA generally prefers short duration crops like vegetables, annual flowers, ornamental trees, seasonal spices and herbs, aromatic plants and mushrooms. These can be grown for human consumption and ornamental use within and in the immediate surroundings of cities with rural agriculture continuing to be the primary source of basic food for urban dwellers also. Horticultural crops assume greater significance in the context of UPA and it is more of urban and peri-urban horticulture (UPH). Protected cultivation techniques are available to force fruits, vegetables and flower crops to grow off season. Hydroponics, aeroponics and aquaponics are possible methods of growing crops saving space, time, energy and labor. Biotechnology and nutraceuticals 12 Nutraceuticals are functional foods based on the philosophy of using food as preventive medicine. Biotechnology provides tools to enhance active components in food. Any food or part of food or nutrient that provides health benefits, including prevention and treatment of a disease qualify to be called nutraceuticals. Since the introduction of the first genetically modified crop, the "Flavr Savr" tomato in 1994, "GM" products are now found in thousands of foods, from bagels to butter tarts to soy milk. While the biotech industry points to the safety and benefits of genetic modifications, environmentalists are quick to denounce it for potential harm to biodiversity. Products like Fenulife (Fenugreek galactomannon combination) which control blood sugar, Golden Rice “swarna” which is rice genetically modified to contain high levels of beta-carotene, which the body can convert into vitamin A indicate emerging role of this class of food. In “swarna” rice modification is done using genes from a daffodil, a pea, a bacterium and a virus. As many as 500,000 children go blind each year due to vitamin A deficiency, and this new rice is being touted as biotechnology at its best to solve problems of food insecurity. It is estimated that 134 m ha are brought under transgenic crops since 1966 of which 46% are in developing countries (China, India, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and South Africa) and in crops like Soybean, Maize, Cotton, and Canola. More than 50 crops and forestry trees are being targeted currently . Tissue culture propagation of plating material for horticultural crops is making waves in banana,ginger,cardamom and ornamentals. References 1.Ali M. Yusuf, M. MustaqueAhmed and Badirul Islam,M .(2008). “Homestead Vegetable Gardening: Meeting The 13 Need Of Year Round Vegetable Requirement of Farm Family” Paper presented in the National workshop on Multiple cropping held at Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh on 23-24 April, 2008. 2.Asaduzzaman Md, Naseem A and Singla ,R .(2011). Benefit-Cost Assessment of Different Homestead Vegetable Gardening on Improving Household Food and Nutrition Security in Rural Bangladesh, Paper presented at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2011 AAEA & NAREA Joint Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, July 24-26, 2011 3.FAO (2008). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2008. Economic and Social Development Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. Rome 4.FAO (2010). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2010. Economic and Social Development Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. Rome 5FAO,( 2012),) Food Insecurity in the World, Food and Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations, Rome, 2012 6.Iannotti ora , Kenda Cunningham and Marie Ruel (2009) Improving Diet Quality and Micronutrient Nutrition Homestead Food Production in Bangladesh IPRI Discussion Paper 00928 7.IFPRI. (2009). Global Hunger Index. Washington, DC, IFPRI (www.ifpri.org/millionsfed) 8.John, J. and Nair, M. A. (1999). Socio-economic characteristics of homestead farming in south Kerala Journal of Tropical Agriculture 1999 Vol. 37 No. 1/2 pp. 107-109 9. NAAS. (2009), State of Indian Agriculture- A NAAS Publication. National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, New Delhi 14 10.Nair, P.K.R and Kumar, B.M .(2006). Introduction in Tropical Home gardens , Springer, Netherlands, P 1-10 11.Salam, M.A., Noguchi T., and Koika, M.( 2000). Understanding why farmers plant trees in the homestead agro-forestry in Bangladesh. Agroforestry Systems. 50. 77-93 12.Sen, A. (1981) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (Oxford, Clarendon Press). 13.Tejwani, K. G. (1994). Agroforestry in India, Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi. 15 Table 1. Trends in Global undernutrition (1990-92 base year) Sl. No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Country/Region World Developing countries India China Asia Pacific (excluding India & China) East & North Africa Developed countries Latin America & Carribia Sub Saharan Africa 1990-92 million(%) 842 823 207(26) 178(21) (22) 19(2) 19(2) 53(6) 169 (20) 2003-2005 million(%) 848 832 231(28) 123(14) 33(4) 16 (2) 45 (5) 212 (25) Source : FAO 2008 Table :2. Number and percentage of under nourished people in India since the base year 1990-1992 Year Total population (million) 1990-92 1995-97 863 949 16 Undernourishment Number(mill Percenta ion) ge 215 25 202 21 2001-03 2005-07 2009-10 1050 1116 1168 212 221 250 17 20 20 21 Table 3. Contributions of the three components of Global Hunger Index (GHI) and the underlying data for calculating the 1990 and 2010 GHI Proportion Prevalence of Country of under underweight nourished in in children the under 5 years population (%) (%) 1990- 2004- 1990- 200392 06 92 08 India 24.0 22.0 59.5 43.5 Bangladesh 36.0 26.0 56.5 41.3 China 15.0 10.0 15.3 6.0 Pakistan 22.0 23.0 39.0 25.3 World Source: Global Hunger Index, IFPRI, 2010 Under five GHI mortality With rate (%) data from 198892 1990 2008 1990 With data from 200308 2010 11.6 14.9 4.6 13.0 - 24.1 24.2 6.0 19.1 15.1 6.9 5.4 2.1 8.9 - 31.7 35.8 11.6 24.7 19.8 Table 4. Levels of malnutrition among vulnerable sections of the population (%)in India Indicators Children under 3 years who are stunted 18 NFHS-2 1998-99 45.50 NHFS-3 2005-06 38.40 Children under 3 years who are wasted: 15.50 19.10 weight for height Children under 3 years who are 47.0 45.9 underweight: weight for age-less than 2 S.D Anaemia among children aged 6 to 59 74.0 70.0 months Women in 15 to 24 years in BMI 18.5 NA 44.1 Women in age 25 to 49 year BMI 18.5 NA 30.7 Women in age 15 to 49 year BMI 18.5 36.2 35.6 Source: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India Table 5.Achievement in Wheat Production over the years Sl. no Period Production 1 Earliest evidence cultivation 2 Production in 1947-48 06 million tones 3 Production in 1963-64 10 million tones 4 Production in 1967-68 17 million tones 5 Production in 2012 92 million tones of Mohanjo-daro excavations 2300 BC 19 Table 6. Required growth over the base year production of 2006-07 to achieve domestic demand by 2020 Commodity Domestic production (million tons) Projected Growth demand rate during 1998-99 to (2020-21) 200607(%) (million tones) Required growth rate over 2006-07 to meet the demand (%) Cereals 201.9 262.0 0.62 1.9 Pulses 14.2 19.1 0.47 2.1 Food grains 216.1 281.1 0.61 1.9 Oilseeds 23.6 53.7 1.96 6.0 Vegetable 111.8 127.2 3.68 0.9 Fruit 57.7 86.2 3.06 2.9 Sugarcane 315.5 345.3 -0.60 0.6 Milk 100.9 141.5 3.65 2.4 Fish 6.9 11.2 2.89 3.5 Egg (billion) 50.7 81.4 6.60 3.4 2006-07 Table 7 Statistics of farming population over total population of India 20 Total Population Farming Population Small and farmers (Million) (Million) (Million) Male 530 318 249 Female 495 297 249 Total 1025 615 498 Family Fig.1. World commodity prices 600 120 500 100 400 80 300 60 200 40 100 20 US$/barrel Maize Rice Wheat 21 Oil Mar-13 Feb-13 Jan-13 Jan-12 Jan-11 Jan-10 Jan-09 Jan-08 Jan-07 Jan-06 Jan-05 Jan-04 Jan-03 Jan-02 0 Jan-01 0 Jan-00 US$/ton World Commodity Prices, Jan 2000 - Mar 2013 Fig.2. Per worker GDP in agriculture and non-agriculture sectors, Rs at 1999-00 prices 100000 90000 80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 1987-88 1999-00 Agriculture 22 Non-Agriculture 2004-05 23 24