The Italian American Experience

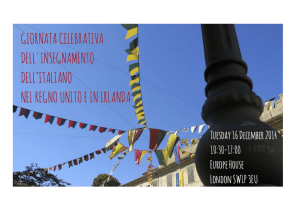

advertisement