Chapter 2: Opportunity costs

advertisement

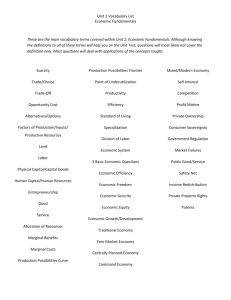

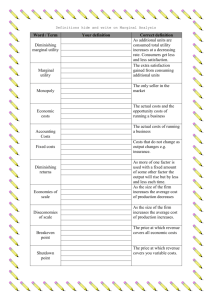

Chapter 2: Opportunity costs Scarcity Economics is the study of how individuals and economies deal with the fundamental problem of scarcity. As a result of scarcity, individuals and societies must make choices among competing alternatives. Opportunity Cost The opportunity cost of any alternative is defined as the cost of not selecting the "nextbest" alternative. Example: Suppose that you own a building that is worth $100,000 today and is expected to be worth $100,000 one year from today. If the interest rate is 10%, what is the opportunity cost of using this building for one year? Example II The opportunity cost of college attendance includes: the cost of tuition, books, and supplies, foregone income (this is usually the largest cost associated with college attendance), and psychic costs. What about room and board? Example III: Opportunity cost of attending a movie: opportunity cost of tickets opportunity cost of time Marginal analysis Marginal benefit = additional benefit resulting from a one-unit increase in the level of an activity Marginal cost = additional cost associated with one-unit increase in the level of an activity Net benefit Individuals are not expected to maximize benefit; nor are they expected to minimize costs. Individuals are assumed to attempt to maximize the level of net benefit (total benefit minus total cost) from any activity in which they are engaged. Marginal analysis MB > MC expand the activity MB < MC contract the activity optimal level of activity: MB = MC (Net benefit is maximized at this point) Marginal benefit MB generally declines as the level of an activity rises, ceteris paribus. Consider the MB of time spent studying: Marginal cost For most activities, marginal cost rises as the level of the activity increases. Optimal study time The optimal amount of study time occurs at the point at which MB = MC Production possibilities curve Assumptions: A fixed quantity and quality of available resources A fixed level of technology Efficient production (i.e., no unemployment and no underemployment) Example: study time 4 hours left to study for two exams: economics and calculus Output = grades on each exam Fixed resources? Fixed technology? No unemployed nor underemployed resources? Alternative uses of time Law of diminishing returns Law of diminishing returns: output will ultimately increase by progressively smaller amounts when the use of a variable input increases while other inputs are held constant. Does this apply in this example? What are the fixed inputs? Production possibilities curve Marginal opportunity cost Marginal opportunity cost = the amount of another good that must be given up to produce one more unit of a good. Calculating marginal opportunity cost In the interval between points A and B, the marginal opportunity cost of 1 point on the economics exam is 1/3 of a point on the calculus exam. Marginal Opportunity Cost (continued) In the interval between points B and C, the marginal opportunity cost of one point on the economics exam equals 4/3 of a point on the calculus exam. Law of increasing cost Law of increasing cost – marginal opportunity cost rises as the level of an activity increases Reasons for law of increasing cost Law of diminishing returns Specialized resources (heterogeneous labor, land, capital, etc.) Specialized resources in farming Some land, labor, and capital is better suited for wheat production and some is better suited for corn production Unemployed or underemployed resources Points outside of the PPC Economic growth Commodity-specific technological change Specialization and trade Adam Smith – economic growth is caused by increased specialization and division of labor. Gains from specialization and division of labor specialization in areas that match the skills and talents of workers “learning by doing” – increase in productivity from task repetition less time lost while switching from task to task Specialization and trade As noted by Adam Smith, specialization and trade are inextricably linked. Adam Smith and David Ricardo used this argument to support free trade among nations. Absolute and comparative advantage Absolute advantage – an individual (or country) is more productive than other individuals (or countries). Comparative advantage – an individual (or country) may produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than can other individuals (or countries). Example: U.S. and Japan Suppose the U.S. and Japan produce only two goods: CD players and wheat. Absolute advantage? Who has an absolute advantage in producing each good? Comparative advantage? Who has a comparative advantage in producing each good? Gains from trade Opportunity cost of CD player in U.S. = 2 units of wheat Opportunity cost of CD player in Japan = 4/3 unit of wheat If Japan produces and trades each CD player to the U.S. for more than 4/3 of a unit of wheat but less than 2 units of wheat, both the U.S. and Japan gain from trade and can consume more goods than they could produce by themselves. Gains from trade (continued) Note that the U.S. has a comparative advantage in producing wheat. Countries always expand their consumption possibilities by engaging in trade (since they acquire goods at a lower opportunity cost than if they produced them themselves). Free trade? If each country specializes in the production of those goods in which it possesses a comparative advantage and trades with other countries, global output and consumption in increased.