History of Catalog(u)ing

advertisement

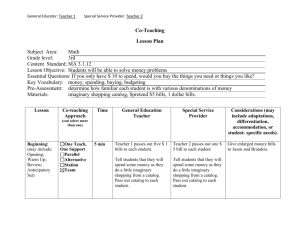

Cataloging and Classification Plymouth State University LM 5020 Nancy J. Keane, MLS, MA Who are we? Syllabus Time line History of Catalog(u)ing My library hero Five Laws of Library Science Books are for use. Every person his or her book. Every book its reader. Save the time of the reader. The library is a growing organism. How do we achieve these? One way is through cataloging But what is that? cat·a·log or cat·a·logue ŏg') Pronunciation Key n. (kāt'l-ôg', - A list or itemized display, as of titles, course offerings, or articles for exhibition or sale, usually including descriptive information or illustrations. A publication, such as a book or pamphlet, containing such a list or display: a catalog of fall fashions; a seed catalog. A list or enumeration: "the long catalogue of his concerns: unemployment, housing, race, drugs, the decay of the inner city, the environment and family life" (Anthony Holden). A card catalog. -- dictionary.com v. cat·a·loged or cat·a·logued, cat·a·log·ing or cat·a·logu·ing, cat·a·logs or cat·a·logues v. tr. To make an itemized list of: catalog a record collection. To list or include in a catalog. To classify (a book or publication, for example) according to a categorical system. v. intr. To make a catalog. To be listed in a catalog: an item that catalogs for 200 dollars. Why do we need a catalog? First catalogs Inventory lists Librarian responsible for collection and could be charged for lost materials Shelf order The next wave Babylonia and Assyria too large for inventory list Subject arrangement Call numbers used The art of catalog(u)ing born Types of Catalogs Used Book Catalog (used until late 19th century) Advantage – Portable. Multiple copies could easily be made. Remote access. Book Catalog Disadvantage – Not flexible. Costly to update - Difficult to revise Susceptible to wear and tear and loss Came back into vogue in 1960s Card Catalogs Came into use in the late 19th century. Used 3x5 cards which could be purchased from LC in 1901 Advantages – Easy to add to and discard from. Very flexible Card catalog Disadvantages – can reach enormous size. Doubled every 20 years. Expensive to maintain. Vulnerable to theft or destruction. Computerized catalogs Came into vogue in late 1970s. Found in most libraries today. Advantages – Extremely flexible. Never out of date. Easy to maintain. Computerized catalog Disadvantages – expensive!! Initially, much more work than conventional catalogs. Cannot be used without expensive equipment. Variations of computerized catalog Fiche catalog Book catalog Card catalog CD-ROM catalog Web catalog Organization of the catalog No matter what form, the catalog must be organized or it is unusable. Arranged in a logical, consistent manner Early schemes Classed catalog Like the shelf list but material can have more than one class number. Virtually extinct Dictionary catalog Late 19th century All entries interfiled (author, title, subject) Allows patron complete access to collection from single file. In card catalog, filing was a nightmare. Divided catalog 1930s Author/title Subject Easier to maintain Harder for patrons. (eg Shakespeare as author or subject) Cataloging rules A set of rules is essential to maintain order Patrons must be able to depend on consistency of elements Cataloging rules As many rules as there are libraries! Sir Anthony Panizzi in 1841 – first major set of rules – “Rules for the Compilation of the Catalogue” Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Musuem. It had been developed for the British Museum in 1839 and consisted of 91 rules – 5 pages long. Jewett’s rules (1850s) Charles Jewett based his rules on Panizzi’s. Developed for Smithsonian 33 rules Earliest attempt at codifying subject heading practice Jewett proposed “stereotyped” cataloging (was eventually fired for his radical ideas) Cutter’s rules (1876) Contained 369 rules covering descriptive cataloging, subject headings, and filing. Have had a great impact on current rules Defined why we catalog: Objects of catalog AA 1908 American Library Association (88 p.) Represented the first joint effort between American and British librarians in developing a code Geared to major libraries “of a scholarly character” not public libraries (Cutter took care of these) No subject access addressed Prussian Instructions (1908) Standardized instructions for Prussian libraries Major difference with AngloAmerican edition: Grammatical title No corporate author Vatican Code (1920s) Developed for cataloging books in the Vatican Best structured code at the time Called the most complete statement of American practice Used examples throughout ALA draft (1941) Intended to be international but with outbreak of World War II, it didn’t happen Now 408 pages long (up from 88) Standardization needed for centralized processing Two parts – entry and headings ; description Library of Congress rules (1949) Since most libraries buying cards from LC, need to publish rules used Not totally compatible with ALA rules Description only Many formats addressed ALA Rules (1949) Complemented LC rules Only rules for entry and headings. International Conference on Cataloguing Principles (1961) Paris Principles Addressed the criticism of current code Great step toward international code Good intentions but cost of change enormous Compromise Two codes developed AACR (1967) North American edition and British edition Mixed reviews Controversial policy of “superimposition” ISBD Copenhagen 1969 Objective: Internationally understood Records can be integrated Records can easily be converted to machine readable form Two standards adopted: ISBD(N) and ISBN(S) AACR II (1978) ISBD LC doing away with superimposition International standards Universal bibliographic control Worked on from 1973 to 1977 Draft received over 1000 pages of comments Final code 620 p. AACR II 2 parts – description (based on ISBD) – headings, uniform titles and references (based on Paris Principles) Contains options for individual consideration. Effort to use British terms. AACR II Revised 1988 Revised to cover 10 years of interpretations Effort to include new media 677 p. AACR II Revised 1998 836 p. AACR II Revised 2005 Now published in looseleaf An incredible 705 p. What’s next? Just so you don’t get too comfortable – The new rules RDA – Resource description and access What is RDA? Resource Description and Access Working title for a new cataloguing code based on the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR). World’s most used content standard for bibliographic description and access Why is it needed? To simplify the rules to encourage use as an international content standard for metadata Provide more consistency and less redundancy for easier use and interpretation Improve collocation in displays through work/expression relationships and a new approach to General Material Designations Why is it needed? Get back to more principle-based rules that build cataloguers’ judgement Founded on international cataloguing principles Encourage the application of the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records model Recent history 1997: International Conference on the Principles and Future Development of AACR, Toronto. Worldwide experts invited by JSC identified issues: Principles Content vs Carrier Logical structure of the Rules Seriality Internationalization Recent history 1998: FRBR published by IFLA. Reinforces basic objectives of catalogues and importance of relationships for users to carry out basic tasks: Find – Identify – Select – Obtain Structure allows collocation at Work/Expression level Conceptual model of entities, relationships and attributes independent of communication format or data structure FRBR – What Are We Cataloging? • Library collections Books – Serials – Maps, globes, etc – Manuscripts. – Musical scores – A-V – • sound recordings • motion pictures • photographs, slides – Multimedia – “Remote” digital materials FRBR entities Products of intellectual & artistic endeavor –Work –Expression –Manifestation –Item “Book” Physical item (item) “publication” at bookstore any copy (manifestation) “Book” –Who translated? (expression) –Who wrote? (work) Recent history 2003-2007: IFLA updates and reaffirms Paris Principles. Regional meetings, world-wide Incorporates FRBR concepts Focussing on current environment of online catalogues and planning for future systems “Cataloguing” today Need to provide access to a wider range of information carriers, with a greater depth and complexity of content Bibliographic metadata is created by a wider range of personnel Authors, administrators, cataloguers, computers, etc. Varying levels of skill and ability (and cost) Many new metadata formats Formats Metadata packaging (communication) standards MAchine Readable Cataloging (UNIMARC, MARC21, MODS/MADS, MARCXML) Dublin Core, Encoded Archival Description, ISBD, VRA, MPEG7, …!!! Cataloguing rules need to remain independent of any communication format JSC Strategic plan JSC Strategic plan goals Continue to base rules on principles, and cover all types of materials Foster use world-wide, while deriving rules from Anglophone conventions and customs Make rules easy to use and interpret Make applicable to an online, networked environment Provide effective bibliographic control for all types of media Make compatible with other similar standards Encourage use beyond the library community Strategic plan targets New code in 2008 New introductions; content rules and updated examples; authority control; FRBR terminology; simplification to reduce redundancy and improve consistency Reach out to other communities to achieve greater alignment with other standards Web-based product/tool as well as loose-leaf With added functionality (e.g. internal and external links to specific rules) and interoperability with cataloguing and access tools Demo (http://www.rdaonline.org/) shows integration with data input templates and task-oriented workflow Recap RDA is a new standard for resource description and access, designed for the digital environment Multinational content standard covering all media Independent of technical communication formats Aimed at all who need to find, identify, select, obtain, use, manage and organize information