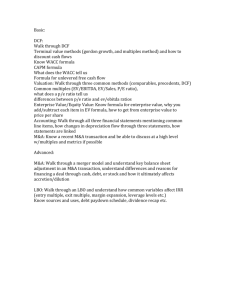

Valuation - edbodmer

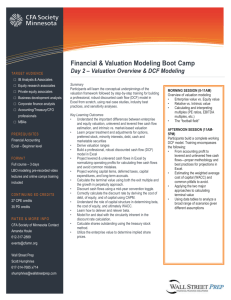

advertisement