25.11.15 16.00 Dworkin

Reading Seminar on 20th

Century Legal Philosophy

Introduction: Hart, Finnis, Fuller, Dworkin

Marko Kairjak, PhD (Tartu), LLM

(Cantab.)

Time schedule for the Course

• 09.11.15 16.00 General Introduction

• 12.11.15 16.00 Hart , Concept of Law

• 16.11.15 16.00 Finnis , Natural Law and

Natural Rights

• 20.11.15 16.00 Fuller , Morality of Law (+

Simmonds)

• 25.11.15 16.00 Dworkin , Law’s Empire

Introduction

" /…/ for the moment , anyway , political philosophy is dead " (Laslett 1956:vii).

Hobbes

T. Hobbes, Leviathan (1651), see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3207/3207-h/3207h.htm#link2H_PART2

“The finall Cause, End, or Designe of men, (who naturally love Liberty, and Dominion over others,) in the introduction of that restraint upon themselves, (in which wee see them live in Common-wealths,) is the foresight of their own preservation, and of a more contented life thereby; that is to say, of getting themselves out from that miserable condition of Warre, which is necessarily consequent (as hath been shewn) to the naturall Passions of men, when there is no visible Power to keep them in awe, and tye them by feare of punishment to the performance of their Covenants, and observation of these Lawes of Nature set down in the fourteenth and fifteenth Chapters.

”

Hobbes

T. Hobbes, Leviathan (1651), see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3207/3207-h/3207h.htm#link2H_PART2

“The attaining to this Soveraigne Power, is by two wayes.

One, by Naturall force; as when a man maketh his children, to submit themselves, and their children to his government, as being able to destroy them if they refuse, or by Warre subdueth his enemies to his will, giving them their lives on that condition. The other, is when men agree amongst themselves, to submit to some Man, or Assembly of men, voluntarily, on confidence to be protected by him against all others. This later, may be called a Politicall Common-wealth, or Common-wealth by Institution; and the former, a

Common-wealth by Acquisition. And first, I shall speak of a

Common-wealth by Institution..

”

Hobbes

T. Hobbes, Leviathan (1651), see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3207/3207h/3207-h.htm#link2H_PART2

“Institution Of The Soveraigne Declared By The Major Part. Thirdly, because the major part hath by consenting voices declared a Soveraigne; he that dissented must now consent with the rest; that is, be contented to avow all the actions he shall do, or else justly be destroyed by the rest.

For if he voluntarily entered into the Congregation of them that were assembled, he sufficiently declared thereby his will (and therefore tacitely covenanted) to stand to what the major part should ordayne: and therefore if he refuse to stand thereto, or make Protestation against any of their

Decrees, he does contrary to his Covenant, and therfore unjustly. And whether he be of the Congregation, or not; and whether his consent be asked, or not, he must either submit to their decrees, or be left in the condition of warre he was in before; wherein he might without injustice be destroyed by any man whatsoever ”

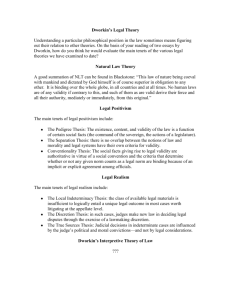

Hart

Three distilled issues: a) Legal obligation b) Political obligation c) Political sovereignity

Hobbes did not answer to a.

Hart

• HLA Hart, The Concept of Law, 1961.

• From the three distilled questions:

• “a) Legal obligation” remained as teh cornerstone of legal philosophy

• b) and c) remained the objects of political philosophy

Hart

• Question a) was divided into two:

• It is not a moral question

• It is a moral question

Hart

• It is not a moral question – legal positivists:

( Bentham, Austin, Kelsen ), Hart , Raz, Kramer,

Dworkin

• It is a moral question – natural law theory:

( Aquin ), Finnis , Fuller , Simmonds, Dworkin

Elmer case

Riggs v. Palmer, 115 N.Y. 506 (1889)

Plaintiffs, Mrs. Riggs and Mrs. Preston, sought to invalidate the will of their father Francis

B. Palmer. The defendant in the case was Elmer E. Palmer, grandson to the testator. The will gave small legacies to two of the daughters, Mrs. Preston and Mrs. Riggs, and the bulk of the estate to Elmer Palmer to be cared for by his mother, Susan Palmer, the widow of a dead son of the testator, until he became of legal age. Knowing that he was to be the recipient of his grandfather's large estate, Elmer, fearing that his grandfather might change the will, murdered his grandfather by poisoning him. The plaintiffs argued that by allowing the will to be executed Elmer would be profiting from his crime. While a criminal law existed to punish Elmer for the murder, there was no statute under either probate or criminal law that invalidated his claim to the estate based on his role in the murder.

Judge Robert Earl (in office 1870 and 1875 –1894) wrote the majority opinion for the court, which ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. The court reasoned that tenets of universal law and maxims would be violated by allowing Elmer to profit from his crime. The court held that the legislature could not be reasonably expected to address all contingencies in crafting laws and that, had they reason to suspect one might behave in the manner

Elmer did, they certainly would have addressed that situation.

Elmer case

- Pivotal/hard cases

- Do we have to follow the letter fo law?

R vs Hinks

R v Hinks [2000] UKHL 53 is an English case heard by the House of Lords on appeal from the Court of Appeal of England and Wales.

In 1996 Miss Hinks was friendly with a 53-year-old man, John Dolphin, who was of limited intelligence. She was his main carer. During 1996 Mr Dolphin withdrew around

£60,000 from his building society account, which was deposited in Miss Hinks's account.

In 1997 Hinks was charged with theft. During the trial, Mr Dolphin was described as being naïve and trusting and having no idea of the value of his assets or the ability to calculate their value. However, it was said that he would be capable of making a gift and understood the concept of ownership. Mr Dolphin was capable of making the decision to divest himself of money, but it was unlikely that he could make this decision alone. The defendant's argument was that the moneys were a gift from Mr Dolphin to Hinks, and that given that the title in the moneys had passed to her, there could be no theft.

She appealed to the Court of Appeal on the grounds, inter alia, that since she acquired a perfectly valid gift, there could not be an appropriation. The Court of Appeal rejected this ground of appeal, stating that the fact there has been made a valid gift is irrelevant to the question of whether there has been an appropriation. Indeed, it held that a gift may be evidence of an appropriation.

R vs Hinks (cont.)

The case concerned the interpretation of the word "appropriates" in the

Theft Act 1968. The relevant statute is as follows:

Section 1 provides: "(1) A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it..."

Section 3 provides: "(1) Any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner amounts to an appropriation..."

The court established that in the English law of theft, the acquisition of an indefeasible title to property is capable of amounting to an

Appropriation of property belonging to another for the purposes of the

Theft Act 1968. Therefore, a person can appropriate property belonging to another where the other person makes him an indefeasible gift of property, retaining no proprietary interest or any right to resume or recover any proprietary interest in the property.

R v Hinks (cont.)

Lord Steyn in Hinks:

“ The purposes of the civil law and the criminal law are somewhat different. In theory the two systems should be in perfect harmony. In a practical world there will sometimes be some disharmony between the two systems. In any event, it would be wrong to assume on a priori grounds that the criminal law rather than the civil law is defective .”

R v Hinks (cont.)

Rather (in)famous sentence from Lord Hobhouse’s dissenting opinion from Hinks should be quoted:

“To treat otherwise lawful conduct as criminal merely because it is open to [moral] disapprobation would be contrary to principle and open to the objection that it fails to achieve the objective and transparent certainty required of the criminal law by the principle basic to human rights.”

Conclusion

• Result:

• Contradictions within one field of law (criminal law)

• Contradictions within the law itself.

• Legal positivists vs natural law: different results in two hard cases

Questions to be answered

- Is there any thing called law? If yes what it is?

- Do we have to always obey law?

- Is reasoning of non-obediance also law? Does non-obediance have to be reasoned? If yes then based on what?

Questions to be answered – Hart

- Is there any thing called law? If yes what it is?

- Hart vs Austin, two levels of law

- Do we have to always obey law?

- Rule of recognition

- Do we have a choice?

- Is reasoning of non-obediance also law? Does non-obediance have to be reasoned? If yes then based on what?

- Why follow?

- What will follow after obediance?

- Is Hart a legal sociologist?

Time schedule for the Course

• 09.11.15 16.00 General Introduction

• 12.11.15 16.00 Hart , Concept of Law (please read chapters 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 of the book)

• 16.11.15 16.00 Finnis , Natural Law and Natural Rights, please read the summary http://homepage.westmont.edu/hoeckley/readings/Sym posium/PDF/201_300/253.pdf

• 20.11.15 16.00 Fuller , Morality of Law (reading the whole book is fine, it is not that long)

• 25.11.15 16.00 Dworkin , Law’s Empire (or Dworkin,

Taking Rights Seriously) – please read two articles: GJ

Postema, Integrity: Justice in workclothes, TRS Allan,

The Rule fo Law as Integrity (both available online)