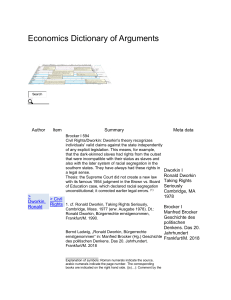

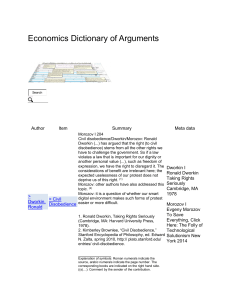

Dworkin's Legal Theory

advertisement

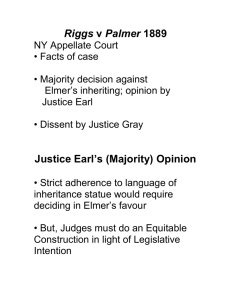

Dworkin’s Legal Theory Understanding a particular philosophical position in the law sometimes means figuring out their relation to other theories. On the basis of your reading of two essays by Dworkin, how do you think he would evaluate the main tenets of the various legal theories we have examined to date? Natural Law Theory A good summation of NLT can be found in Blackstone: “This law of nature being coeval with mankind and dictated by God himself is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over the whole globe, in all countries and at all times. No human laws are of any validity if contrary to this, and such of them as are valid derive their force and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.” Legal Positivism The main tenets of legal positivism include: The Pedigree Thesis: The existence, content, and validity of the law is a function of certain social facts (the command of the sovereign, the actions of a legislature). The Separation Thesis: there is no overlap between the notions of law and morality and legal systems have their own criteria for validity. Conventionality Thesis: The social facts giving rise to legal validity are authoritative in virtue of a social convention and the criteria that determine whether or not any given norm counts as a legal norm are binding because of an implicit or explicit agreement among officials. Legal Realism The main tenets of legal realism include: The Local Indeterminacy Thesis: the class of available legal materials is insufficient to logically entail a unique legal outcome in most cases worth litigating at the appellate level. The Discretion Thesis: in such cases, judges make new law in deciding legal disputes through the exercise of a lawmaking discretion. The True Sources Thesis: Judicial decisions in indeterminate cases are influenced by the judge’s political and moral convictions—and not by legal considerations. Dworkin’s Interpretive Theory of Law ??? Riggs v. Palmer On the 13th day of August 1880, Francis B. Palmer made his last will and testament, in which he gave small legacies to his two daughters, Mrs. Riggs and Mrs. Preston, the plaintiffs in this action, and the remainder of his estate to his grandson, the defendant Elmer E. Palmer…. At the date of the will, and subsequently to the death of the testator, Elmer lived with him as a member of his family, and at his death was 16 years old. He knew of the provisions made in his favor in the will, and, that he might prevent his grandfather from revoking such provisions, which he had manifested some intention to do, and to obtain the speedy enjoyment and immediate possession of his property, he willfully murdered him by poisoning him. He now claims the property. The sole question for our determination is, can he have it? Issue: Whether Elmer Palmer should be permitted to inherit his grandfather’s fortune, given that he murdered his grandfather for the express purpose of receiving his inheritance. Some relevant facts: The Statute of Wills, read literally, made it clear that the grandson would inherit, the murder notwithstanding. There were no statutes in effect which prohibited Elmer from inheriting the fortune. For all intents and purposes, the will was a valid legal document. How ought we to rule in this case? Are we “bound by the rigid rules of law” (as Justice Gray asserts in his dissenting opinion)? As Gray wrote: I concede that rules of law which annul testamentary provisions made for the benefit of those who have become unworthy of them may be based on principles of equity and of natural justice. It is quite reasonable to suppose that a testator would revoke or alter his will, where his mind has been so angered and changed as to make him unwilling to have his will executed as it stood. But these principles only suggest sufficient reasons for the enactment of laws to meet such cases. Or do you find yourself agreeing with Justice Earl (and Ronald Dworkin)? What could be more unreasonable than to suppose that it was the legislative intention in the general laws passed for the orderly peaceable, and just devolution of property that they should have operation in favor of one Who murdered his ancestor that he might speedily come into the possession of his estate? Such an intention is inconceivable. We need not, therefore, be much troubled by the general language contained in the laws. Besides, all laws, as well as all contracts, may be controlled in their operation and effect by general, fundamental maxims of the common law. No one shall be permitted to profit by his own fraud, or to take advantage of his own wrong, or to found any claim upon his own iniquity, or to acquire property by his own crime. These maxims are dictated by public policy, have their foundation in universal law administered in all civilized countries, and have nowhere been superseded by statutes.