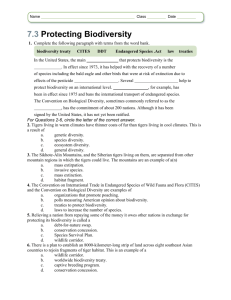

Annex 10. Original Description of Project Sites – Corridors and Focal

advertisement