The Second Continental Congress The first successful British

advertisement

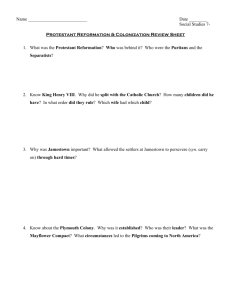

The Second Continental Congress The first successful British settlement in the New World began in 1607, when the Virginia Company of London received a charter from King James I of England (VI of Scotland) to establish a permanent settlement in the Chesapeake region of North America.1 A mere twelve years later in 1618, the first representative assembly in the New World convened in Jamestown under the orders of the Virginia Company to create “one equal and uniform government over all Virginia.”2 Thus began America’s tradition of representative self-government. Other colonies soon followed. For varying reasons, colonists sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in search of opportunity. In 1620, a group of Puritan separationists known as the Pilgrims established the first settlement in what later became the Province of Massachusetts Bay.3 They sought religious freedom and self-governance, unmolested by the Church of England an ocean away. In 1623, John Mason received land grants between the rivers Merrimack and Sagadahoc, creating the colony of New Hampshire. Hoping to become wealthy from these grants, Mason invested a great deal of money in the colony, though he died in 1635 and never lived to see it.4 Maryland soon became the fourth of the thirteen colonies in 1632. Like the Puritan colony of Massachusetts, Maryland’s founders had religious motivations for settlement. Though Lord Baltimore certainly intended to turn Maryland into a profitable investment, as did John Mason with New Hampshire before him, the colony also existed as a refuge for Catholics fleeing from persecution by the English church.5The founding narrative of Connecticut, the fifth colony, does not vary much from its already established sister colonies. As Puritan settlements expanded in the New World, they began settling in Connecticut in 1635 and received official recognition as a colony in 1636 (though not consolidated fully until 1662).6 The Rev. Thomas Hooker from Boston was one of the key early figures of the colony. In a 1638 sermon, Rev. Hooker declared, “The foundation of authority is laid, firstly, in the free consent of the people.”7 The founders of the next colony, Rhode Island, also came from Massachusetts -- not as Puritan settlers, but as refugees from Puritan orthodoxy. Unable to have their dogmatism assuaged, the Puritan leadership banished reformer Roger Williams from the colony in 1638.8 He 1 http://www.apva.org/history/ Ibid 3 http://www.revolutionary-war.net/13-colonies.html#nh 4 Ibid 5 Ibid 6 Ibid 7 http://connecticuthistory.org/hookers-journey-to-hartford/ 8 http://www.revolutionary-war.net/13-colonies.html#nh 2 and a few others soon established the settlement of Providence. As the Massachusetts colony continued to banish other dissidents, these individuals also moved to Rhode Island in search of the same religious freedom that the Puritans sought less than two decades before. By 1663, some Virginian settlers grew weary of their colony’s own form of legallyenforced piety and moved southward into Carolina. Following the conclusion of the Glorious Revolution in England and the ascension of King Charles II to the throne, the king granted a charter to eight English noblemen called the Lords Proprietors.9 The heirs of these lords later sold their interests to the crown following internal trouble, and Carolina split into two in 1729, becoming royal colonies. After establishing English rule over the Dutch colony of New Netherlands, the land was granted to the Duke of York as a gift and named in his honor. The Duke of York partitioned off southern sections of the colony which later became a colony of their own. Thus began the colonies of New York and New Jersey.10In 1681, William Penn, a Quaker, received a royal charter from King Charles II.11 Penn named the colony after his father (also named William Penn), calling it Pennsylvania. Being a persecuted sect like the Puritans and Catholics before them, the Quakers sought religious independence in the New World. Georgia, by contrast, was the only colony founded in the Eighteenth Century. This colony came considerably later than the others, receiving a royal charter in 1732.12 Though James Oglethorpe’s ideal of a debtor’s colony was never truly realized, settlement in Georgia served a secondary purpose: defense. Concerned by Spanish activity in Florida, King George II granted the charter to the colony (which bears his name) so that it may serve as a buffer between the Spanish and the wealthier colonies of Carolina and Virginia.13 Georgia’s young age produced a stronger bond between itself and the crown than its sisters, and Georgia failed to send any delegates to the First Continental Congress as it needed royal assistance to manage its affairs with the frontier Indian tribes.14 By 1754, the colonial population consisted of approximately 1,500,000 people,15 or slightly less than one-fourth of the population of Britain and Ireland around the same time 9 http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc01.asp http://www.revolutionary-war.net/13-colonies.html#nh 11 http://www.pa.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pa_gov/2966 12 http://www.revolutionary-war.net/13-colonies.html#nh 13 http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/ga01.asp 14 Ferling, John. (2003). A Leap in the Dark. Oxford University Press. p. 112 15 Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, A century of population growth from the first census of the United States to the twelfth, 1790-1900 (1909) p 9 10 period.16 As the colonies expanded westward, conflict erupted. Resulting from disputed claims over French, English, and Spanish control of American territory, the war became, quite literally, a “world war” which took place across Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America.17 In 1763, the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763).18 From it, Britain gained all French land east of the Mississippi River along with Spanish Florida. Immediately afterwards, King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763. The proclamation prohibited colonial settlement beyond the Proclamation Line which ran through the Appalachians. The purpose was to stabilize relationships with the Indian tribes and was not meant to be permanent, but rather extended gradually and lawfully.19 However, this still upset the colonists seeking to settle the hard-won land. To pay off debt resulting from the War, the British government began instituting a series of taxes and other regulations to raise revenue and protect British economic interests. One of the most notable taxes was the Stamp Act of 1765. This act, which applied expressly to the colonies who lacked representation in the Parliament, required a great deal of printed materials to be printed on stamped paper (i.e. paper from London with an embossed revenue seal, indicating taxes had been paid on it) -- these included legal documents, magazines, newspapers, etc.20 The Sugar Act of 1764 existed for the same revenue-raising purpose. This act expanded the Molasses Act of 1733 (which was intended to protect British sugar interests from the cheaper sugar created in the French Indies) by increasing enforcement mechanisms.21 Though the tax on molasses itself was halved, the tax was also applied to a number of other foreign-made commodities, including “sugar, certain wines, coffee, pimiento, cambric and printed calico, and further, regulated the export of lumber and iron.”22 Beginning in 1767, the British government passed another series of acts under Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Called the Townshend Acts, these regulations included a number of pieces of legislation, principally the Revenue Act of 1767, the Indemnity Act, the Commissioners of Customs Act, the Vice Admiralty Court Act, and the New York Restraining Act.23 Deeply dissatisfied, many colonists sought a solution. Some boycotted, some protested, and others harassed royal officials sent to enforce the new legislation. The latter set of issues eventually led to the British occupation of Boston in 1768 to protect those in the colonies 16 http://homepage.ntlworld.com/hitch/gendocs/pop.html Bowen, HV (1998). War and British Society 1688–1815. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-57645-8. 18 http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris763.asp 19 Harvey Markowitz, American Indians (1995) p. 633 20 "The Stamp Act of 1765 – A Serendipitous Find" by Hermann Ivester in The Revenue Journal, The Revenue Society, Vol.XX, No.3, December 2009, pp.87–89. 21 http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/sugaract.htm 22 Ibid 23 Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", p. 128 17 enforcing the new tax collection measures. Two years later, tensions flared during a confrontation between British soldiers and local Bostonians, leading to the Boston Massacre in 1770 which, in turn, caused the government to pursue measures to address the unpopularity of the acts in the colonies.24 A few years later, the British government sought to assist the financially troubled British East India Company (with whom a number of members of parliament had financial interests). It passed the Tea Act of 1773, which met staunch colonial resistance: “Colonists in Philadelphia and New York turned the tea ships back to Britain. In Charleston the cargo was left to rot on the docks. In Boston the Royal Governor was stubborn & held the ships in port, where the colonists would not allow them to unload. Cargoes of tea filled the harbor, and the British ship's crews were stalled in Boston looking for work and often finding trouble. This situation led to the Boston Tea Party.”25 The British response to the Boston Tea Party was swift, passing the “Intolerable Acts” in 1774. However, the colonists had a response of their own. Delegates from twelve of the thirteen (Georgia, again, did not send delegates) colonies convened in Philadelphia to determine the best course of action to alleviate the sufferings of the people of Boston and the colony of Massachusetts. They agreed to boycott British goods, reducing British imports to the colonies by an astounding 97%.27 If their petition to King George III was not addressed, the First Continental Congress called for a Second Continental Congress to be held in 1775 -- this is the Assembly of which you are now a member, beginning in the May of 1775. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April, the colonies await your leadership. It is you who must now decide the proper course of action, and it is you that will decide the fates of the Thirteen Colonies. 26 24 Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", p. 126 http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/teaact.htm 26 http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/intolerable.htm 27 Kramnick, Isaac (ed); Thomas Paine (1982). Common Sense. Penguin Classics. p. 21 25