Excess reserves

advertisement

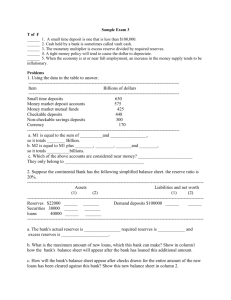

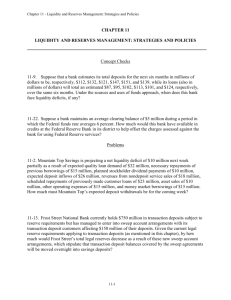

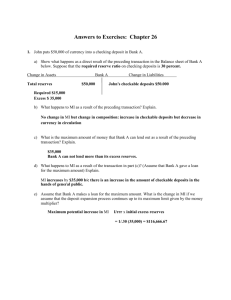

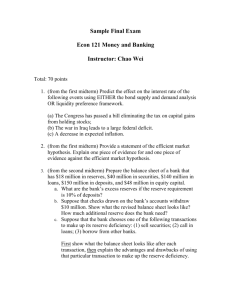

Chapter 32: Money Creation We have seen that the M1 money supply consists of currency and checkable deposits. The U.S. Mint produces the coins and the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing creates the Federal Reserve Notes. So who creates the checkable deposits? The answer is banks. The Fractional Reserve System A fractional reserve banking system requires that a portion of checkable deposits are backed up by reserves of currency in bank vaults or deposits at the central bank. Our goal is to explain this system and show how commercial banks can create checkable deposits by issuing loans. Our analysis applies to banks and thrifts alike. Characteristics of Fractional Reserve Banking First, banks create money through lending. Currency serves as bank reserves so that the creation of checkable deposits by banks, via lending, is limited by the amount of currency reserves that the banks feel obligated, or are required by law, to keep. A second point is that banks operating on the basis of fractional reserves are vulnerable to “panics” or “runs.” A bank would be unable to pay depositors the funds owed to them if they all came to the bank on the same day to withdraw their money. A Single Commercial bank To illustrate the workings of the modern fractional reserve banking system, we need to examine a commercial bank’s balance sheet. The balance sheet is a statement of assets and claims on those assets. Every balance sheet must balance; this means that the value of assets must equal the amount of claims against those assets. The claims shown on a balance sheet are divided into two groups: the claims of nonowners of the bank against the firm’s assets, called liabilities, and the claims of the owners of the firm against the firm’s assets, called net worth. Assets = Liabilities + Net Worth Let’s work through a series of bank transactions involving balance sheets to establish how individual banks can create money. Transaction 1: Creating a Bank The citizens of Wahoo secure a state or national charter for the bank, and then begin selling $250,000 worth of stock to potential investors. In the balance sheet the bank now has $250,000 cash and $250,000 worth of stock outstanding. The cash is an asset to the bank and is sometimes called vault cash or till money. The shares of stock represent the claims of the owners against those assets and are listed under net worth. Notice the T account balances. Transaction 2: Acquiring Property & Equipment The board of directors, who are appointed by the owners to run the bank, now have to purchase property and equipment so the bank can have a physical location. This transaction simply changes the composition of the bank’s assets. The bank has $10,000 in cash and $240,000 in property. Transaction 3: Accepting Deposits Commercial banks have two basic functions: to accept deposits of money and to make loans. The people and businesses of Wahoo now deposit $100,000 in the Wahoo bank. The bank receives $100,000 in cash which is an asset in exchange for $100,000 in checkable deposits which is a liability, or a claim of non-owners against those assets. There has been no change in the economy’s total supply of money as a result of transaction 3, but a change has occurred in the composition of the money supply. Bank money, or checkable deposits, has increased by $100,000, and currency held by the public has decreased by $100,000. A withdrawal of cash will reduce the bank’s checkable deposit liabilities and its holdings of cash by the amount of the withdrawal. This, too, changes the composition, but not the total supply of money in the economy. Transaction 4: Depositing Reserves in a Federal Reserve Bank All commercial banks and thrift institutions that provide checkable deposits must by law keep required reserves. Required reserves are an amount of funds equal to a specified percentage of a bank’s own deposit liabilities. A bank must keep these reserves on deposit with the Federal Reserve Bank in its district or as cash in the bank’s vault. The specified percentage of checkable deposits that a bank must keep as reserves is known as the reserve ratio. It is calculated as the following. Reserve Ratio = bank’s required reserves ÷ bank’s checkable deposits If the reserve ratio is 20%, the Wahoo Bank having accepted $100,000 in deposits from the public, would have to keep $20,000 as a required reserve. The Fed has the authority to establish and vary the reserve ratio within limits legislated by Congress. See table 32.1 for limits. By depositing $20,000 in the Federal Reserve Bank, the Wahoo Bank will just be meeting the reserve ratio. But suppose the Wahoo Bank anticipates that its holdings of checkable deposits will grow in the future. Instead of sending just the minimum amount, $20,000, it sends an extra $90,000, for a total of $110,000. In so doing, the bank will avoid the inconvenience of sending additional reserves each time its checkable deposits increase. Actually, a real-world bank would not deposit all its cash in the Federal Reserve Bank. However, because (1) banks as a rule hold vault cash only in the amount of 1 ½ or 2% of their total assets and (2) vault cash can be counted as reserves, we will assume for simplicity that all of Wahoo’s cash is deposited in the Federal Reserve Bank and therefore constitutes the bank’s actual reserves. There are 3 things to note about this latest transaction. Excess reserves- are found by subtracting its required reserves from its actual reserves. Excess reserves = actual reserves – required reserves The only reliable way of computing excess reserves is to multiply the bank’s checkable deposits by the reserve ratio to obtain required reserves ($100,000 × .20 = $20,000) and then to subtract the required reserves from the actual reserves on the asset side of the bank’s balance sheet. Control- Although historically reserves have been seen as a source of liquidity and therefore as protection for depositors, a bank’s required reserves are not great enough to meet sudden, massive cash withdrawals. So commercial bank deposits must be protected by other means. Periodic bank examinations are one way of promoting prudent banking practices. Furthermore, insurance funds administered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) insure individual deposits in banks and thrifts up to $250,000. If it is not the purpose of reserves to provide for bank liquidity, then what is their function? Control is the answer. Required reserves help the Fed control the lending ability of commercial banks. The Fed can take certain actions that either increase or decrease bank reserves and affect the ability of banks to grant credit. Asset & Liability- The reserves created in transaction 4 are an asset to the depositing commercial bank because they are a claim this bank has against the assets of another institution- the Federal Reserve Bank. Transaction 5: Clearing a Check Drawn against the Bank Assume that Fred Bradshaw has a checkable deposit with the Wahoo Bank and now decides to buy $50,000 of farm equipment from the Ajax Company of Nebraska. Bradshaw pays for the equipment by writing a $50,000 check on his account in the Wahoo Bank and gives it to the Ajax Company. Ajax Company deposits the check in its account with the Surprise bank. The Surprise bank will collect this claim by sending the check to the regional Federal Reserve Bank in its area. The Federal Reserve Bank will adjust the accounts of the 2 banks involved, not the individuals. Finally, the Federal Reserve Bank sends the cleared check back to the Wahoo Bank who then reduces Bradshaw’s account by $50,000. The Wahoo Bank has reduced both its assets and its liabilities by $50,000 whereas the Surprise Bank now has $50,000 more in assets and liabilities. Notice there is no loss of reserves or deposits for the banking system as a whole. What one bank loses, another bank gains. The next 2 transactions are crucial because they explain how a commercial bank can literally create money by making loans and how banks create money by purchasing government bonds from the public. Transaction 6: Granting a Loan In addition to accepting deposits, commercial banks grant loans to borrowers. Suppose Gristly Meat Packing Company wants to take out a loan to expand its facilities and that they want to borrow exactly $50,000 which just happens to be the amount of excess reserves that the Wahoo Bank is holding. Gristly Company hands a promissory note (IOU) to the Wahoo Bank and in exchange receives a checkable deposit in its name on which it can write checks up to $50,000. The Wahoo Bank has an interest earning asset, called loans, and has created checkable deposits to pay for this asset. At the moment the loan is completed, money has been created. Assume now that Gristly uses the loan money to expand its facilities and pays Quickbuck Construction Company to do the work. The $50,000 check is transferred from Wahoo Bank to the Fourth National Bank of Omaha. The check is collected in the manner described in transaction 5 and Wahoo loses both reserves and deposits equal to the amount of the check. The Fourth national bank has now acquired $50,000 in reserves and deposits. After the check has been collected, the Wahoo Bank just meets the required reserve ratio of 20%. The bank has no excess reserves. If a bank creates checkable deposit money when it lends its excess reserves, is money destroyed when borrowers pay off loans? The answer is yes. When loans are paid off, the process works in reverse. The bank’s checkable deposits decline by the amount of the loan repayment. Transaction 7: Buying Government Securities When a commercial bank buys government bonds from the public, the effect is substantially the same as lending. New money is created. Assume the Wahoo bank’s balance sheet stands as it did at the end of transaction 5. Suppose that instead of extending the loan, the bank buys $50,000 of government securities from a securities dealer. The bank receives the interest bearing bonds, which appear on its balance sheet as an asset, and gives the dealer an increase in its checkable deposits account. The bank accepts government bonds, which are not money, in exchange for checkable deposits, which are money. The selling of securities to the public by a commercial bank, like the repayment of a loan, reduces the supply of money. Profits, Liquidity, and the Federal Funds Market The asset items on a commercial bank’s balance sheet reflect the banker’s pursuit of two conflicting goals. Profits- One goal is profit. Banks, like any other business, seek profits, which is why the bank makes loans and buys securities. Liquidity- The other goal is liquidity. For a bank, safety lies in liquidity, specifically assets such as cash and excess reserves. An interesting way in which banks can partly reconcile the goals of profit and liquidity is to lend temporary excess reserves held at the Federal Reserve Banks to other commercial banks. Banks lend these excess reserves to other banks on an overnight basis in order to earn additional interest without sacrificing long- term liquidity. The interest paid on these overnight loans is called the Federal funds rate. The Banking System: Multiple Deposit Expansion This far we have seen that a single bank in a banking system can lend one dollar for each dollar of its excess reserves. The situation is different for all commercial banks as a group. We will make 3 simplifying assumptions The reserve ratio is 20% Initially all banks are meeting this 20% reserve requirement exactly. No excess reserves exist. An amount equal to the excess reserves will be lent to one borrower, who will write a check for the entire amount of the loan and give it to someone else, who will deposit the check in another bank. Suppose a junkyard owner finds $100 while dismantling a car. He then deposits the $100 in bank A, which adds the $100 to its reserves. Reserves and checkable deposits both increase by $100 on the bank’s balance sheet. Of the newly acquired reserves, 20%, or $20 must be set aside as a required reserve. The remaining $80 becomes excess reserves which will be loaned to one customer. Look at table 32.2 to see how this process works its way through all the banks. The result is a $400 increase in the money supply as each bank loans its excess reserves. The Monetary Multiplier The monetary multiplier, or checkable deposit multiplier, exists because the reserves and deposits lost by one bank become reserves of another bank. Monetary multiplier = 1 ÷ required reserve ratio Maximum checkable deposit creation = excess reserves × monetary multiplier In our previous example excess reserves were $80 and the multiplier was 5, so the maximum possible increase in the money supply would be $400. Higher reserve ratios mean lower monetary multipliers and therefore less creation of new checkable deposit money via loans; smaller reserve ratios mean higher multipliers and more creation of new checkable deposit money via loans. Notice in the above equation it says “maximum” checkable deposit creation. However, we need to cite two possible reasons why the money supply may not expand by the full amount possible. Currency drains- Suppose in the original example the junkyard owner had kept $50 in his pocket and deposited the other $50. The money supply would only have expanded by $200, not $400. So when borrows who take out a loan take some of it as cash, rather than a checkable deposit, it won’t end up in the next bank and therefore can’t be loaned to the next customer. Excess reserves- Remember, the Fed sets the minimum reserve requirement that banks must abide by. But is there anything that would prevent banks from setting more aside as a required reserve, over and above what the Fed requires? In the above example the reserve requirement was 20%. But what if the bank chooses to hold 25% aside? How much will the money supply expand now? The answer is $300, not $400.