canon minero transfers - Institute of Development Studies

advertisement

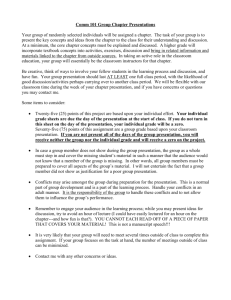

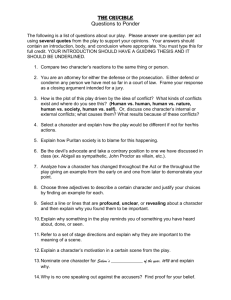

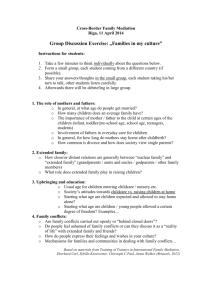

Fiscal transfers and challenges to local public management in mineral economies: canon minero transfers and conflicts in Peru Javier Arellano Yanguas 24th October 2008 London Hosted by Funded by Outline 1. Relevance of sub-national level analysis 2. The Peruvian case 3. Social conflicts and mining in Peru 4. Selection of regions for the research 5. Analysis of conflicts in Peruvian mining regions Relevance of sub-national level analysis I Academic debate about “resource curse” theories to date has predominantly focused on the national level: curses are understood as malfunctions in national economies and polities. The past 15 years have seen changes in polities, three of which are particularly important: a) Decentralisation of authority from national to sub-national levels of government b) Wider scope for citizens’ participation c) More cooperation between state agencies and commercial organisations These measures constitute a widely accepted and promoted “good governance” agenda. Relevance of sub-national level analysis II Simultaneously, international institutions and the mining industry have adopted decentralisation, popular participation and public-private partnership, complemented by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), as a new natural resources policy agenda (NNRPA). Analysis of political dynamics at the sub-national level is crucial to the understanding of how this agenda works. The Peruvian case is a paradigmatic example of the implementation of this agenda: a) Incipient political decentralisation in combination with canon minero; b) Participatory budgeting and other participatory schemes; c) Growing involvement of companies at the local level; Relevance of sub-national level analysis III In the context of a weak Peruvian central state and weaker local governments, the implementation of the NNRPA has relocated the resource curse to sub-national level. Thus, local governments, mining companies and a variety of local actors are locked into complex relationships. The Peruvian case: some figures In 2007, more than 67 % of the total canon transfer was concentrated in just 6 out of 25 regions (Ancash, Cajamarca, Cusco, Moquegua, Pasco and Tacna), accounting for a mere 16 % of the country’s population. Due to massive increases in the canon minero’s monetary value, these six regions, along with their local governments, received more than 52 % of the total revenue transferred by the central government to the local level for investment. While the country on average allocated approximately nuevos soles 426 ($USD 152) per capita for decentralised public investment, mining regions received this figure several times over. Social conflicts and mining Do mining regions take advantage of these transfers? Are they in a comparatively better position? Apparently not: a) They suffer from more frequent social conflicts. b) Public investment is inefficient and not designed to promote development. I will focus mainly on the conflict side. Selection of regions for the research I I selected three regions out of the six receiving the greatest amount of canon minero transfers (it guarantees the importance of current mining activities). Regions with the most municipalities exhibiting two concurrent features: a) In receipt of more than nuevos soles 1,800 per capita of fiscal transfers b) Their population is over 3000 This selection allows research of both the nature of conflicts and the dynamics around public investment at local level. According to these criteria, I selected Ancash (eight municipalities); Moquegua (five municipalities) and Pasco (nine municipalities). I undertook field research from the 1st of April to 29th of September (2008) Selection of regions for the research II The importance of mining is the feature common to the three regions. However, the three cases are dissimilar enough to make them a representative sample of Peruvian mining regions. The following tables give some relevant statistics that characterise these regions and the companies operating in them. Region Area (Km2) Population* Mining as a percentage of regional GDP** 2005 2006 Rural population* Poverty* 2007 Ancash 35915 1,063,459 39.4 49.2 48.6 36 % 42.6% Moquegua 15734 161,533 36.1 37.0 43.1 15 % 25.8% Pasco 25320 280,449 59.3 72.1 74.3 38 % 63.4% * Data for 2007; ** Current prices (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática - Perú, 2008) Companies operating in the three regions REGION / Mine Owners Commencement year* Type Minerals Size Expected lifespan** Employment*** Direct Services 1,700 2,500 ANCASH Antamina BHP Billiton 33.7% Xstrata 33.7% Teckcominco 22.5% Mitsubishi 10% 2001 Open pit Cu , Zn Very large Over 25 years Pierina Barrick 1998 Open pit Au Medium Closing 440 450 Southern CC Grupo Mexico 1976 Open pit Cu Large Over 20 years 1,500 500 Quellaveco Anglo American Awaiting social license Open pit Cu , Mb Large Over 30 years 1,500 MOQUEGUA PASCO Cerro de Pasco Volcan 1903 Underground Open pit (1956) Zn, Pb, Ag Large Long term**** 1,230 1990 Brocal El Brocal 1956 Open pit (1993) Zn, Pb, Ag Medium Long term 275 600 Huarón Pan American Silver 1912 Underground Ag, Zn Medium 15 years 812 570 Atacocha Atacocha 1937 Underground Zn, Ag,, Pb, Cu Medium 8-10 years 390 --- Milpo Milpo 1949 Underground Zn, Pb, Cu Medium 8-10 years 300 600 In some locations, mining activities started before the involvement of the present company; ** According to direct company information or estimated through reserves and production; *** According to company information; **** Dependent on current negotiation with population and authorities. Sources: Company annual reports and personal interviews with employees. Social conflicts and mining I The analysis of conflict around mining in Peru has largely focused on a handful of emblematic cases: Tambogrande, Majaz, Cajamarca, Tintaya... Most of them share two features: a) They are conflict between the mining companies and the local population. b) The local population (or a significant part of it) challenges the existence of the mining operation or its expansion. I argue that the mining bonanza has exacerbated other types of conflicts. I put forward a typology of conflicts that helps to explain their recent increase in Peruvian mining regions and their alignment to canon minero transfers. My classification includes groups and several subgroups: Social conflicts and mining II 1. 2. Conflicts between local population/communities and mining companies: a) Conflicts aiming to stop the construction of new mining operations or the expansion of currently operating ones. b) Conflict as a communal tactic for the preparation of a negotiation process with the company. Conflicts over the control and use of mining revenues: a) Conflicts between the local population and local authorities b) Conflicts between different levels of government c) Conflicts over the control of territory d) Labour conflicts Social conflicts and mining III Conflicts aiming to stop the construction of new mining operations or the expansion of currently operating ones : These have been the most studied. They occur where and when there is a viable economic alternative to mining (real or perceived) and the population thinks that this is incompatible with mining (Tambogrande, Cajamarca, Majaz, Condorhuain, Quellaveco). Economic viability means connection to the marketplace: usually, proximity to a city or town provides the critical mass of people necessary for the conflict to be successful. A wide array of actors (local, national and international) frequently becomes involved in this kind of conflict. This kind of conflicts has not increased in proportion to mining investment. Agriculture and farming must now compete not only with economic opportunities around the mine (reduced ones), but also with the popular expectations of getting a job in the public works financed by canon minero transfers. Social conflicts and mining IV Conflict as a communal tactic for the preparation of a negotiation process with companies These form the majority of the conflicts involving local communities and small towns around mines. Different motives trigger these conflicts: 1. In the context of a mining bonanza companies use profits to expand their operations. They need to negotiate with local communities to obtain land and water. Local communities employ the conflict to reinforce their position in the negotiation process (Rancas, Cerro de Pasco, Huallay, Juprog). 2. The non-fulfilment of company promises and previous agreements: (peasants’ communities around Pierina, Ayash, Carhuayoc, Ilo). Company profits provide an incentive for the population’s claims. 3. Communities’ sense of grievance regarding previous agreements on land transfers. Although the price was freely agreed, the population believes that the current companies’ profits signal unfair deals (Antamina) 4. The local population demands its share in the unprecedented profits (Yarusyakan, Ticlacayan, Huallay). Social conflicts and mining V People feel that conflict is the only way to allow them negotiation on an equal footing with the companies. The local population justifies its claims using different discourses: ecology, ethnicity or social justice. People have a complex and ambiguous relationship with these discourses: a) Such considerations are deeply rooted in the local culture and genuinely constitute people’s identity. b) However, negotiations conclude in agreements on employment, economic compensation, promotion of small businesses, implementation of social projects, etc. Local communities try to negotiate directly with the companies. They do not want other actors to get involved. Conflicts in this subgroup have increased in the last few years because mining companies’ profits prompt them. As canon minero transfers depend on companies’ profits, this partly explains the alignment between conflicts and transfers. Social conflicts and mining VI Conflicts over the control and use of mining revenues This type of conflict has increased dramatically in the last two years. These conflicts are directly related to canon minero transfers. a) Conflicts between local population and local authorities • b) Local authorities’ failure to invest canon minero transfers efficiently (Pasco and Ancash). Conflicts between different levels of government. • Between municipalities and the regional government (openly in Ancash and Pasco). • Between regional governments and the national government: o Modification of the Fondoempleo scheme; o Rules for the distribution of canon minero (Ancash, Moquegua). Social conflicts and mining VII c) Conflicts over the control of territory • Regions and municipalities fight to include under their jurisdiction territories with mining potential and water resources (a key asset for mining development) • Moquegua has different quarrels with Puno, Arequipa and Tacna. • d) Within Moquegua, some districts are fighting amongst themselves (Carumas/San Cristobal; Samegua/Torata). Labour conflicts • In Ancash (Conchucos) and Moquegua the majority of the population works as unskilled labour for the municipalities (thanks to canon minero transfers). These workers earn more than teachers, health workers, police officers, the armed forces, etc. This consequently generates malcontent and mobilisations. Thanks! 41 50 Transferencias de Canon y regalías 4500 3500 3000 16 02 2500 2000 83 4 1500 45 1998 1999 2000 2002 2003 30 8 74 1997 18 3 15 0 1996 95 10 4 500 67 1000 15 Millions of Nuevos Soles Constant prices 1996 4000 0 2001 Source: Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas 2008 Compilation and graphic representation: The author 2004 2005 2006 2007 An ca sh Ta cn a Cu Ca sco ja m ar M oq ca ue gu a Pa sc o L im La Lib a er ta d Lo re to Pi ur a Ca l Ar l ao eq uip a Pu no Hu J an uní n ca ve l ic Uc a ay al i I Tu ca m Ay be s ac u Ap cho ur im Hu a c M ad án u re c de o Sa Di o s n Ma Am rt az ín La o mb nas ay eq ue Millions of Nuevos Soles Transferencias a los departamentos en 2007 2000 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Source: Ministerio de Economía yCanon Finanzas 2008 minero Graphic representation: The author Canon oil Canon Gas Other Canons Other transfers Transferencias per capita a Departamentos 2007 4000 3500 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 Canon Minero Source: Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas 2008 Graphic representation: The author Canon oil canon gas Other canons Other transfers M ar t ín Am az on La as m ba ye qu e n Di os Sa de uc o M ad re Hu án ac o ur im uc h Ap be s Ay ac Ica Tu m li a lic ay a Uc ní n ca ve Hu an Ju no Pu Ca lla o Ar eq ui pa Pi ur a to Lo re a er ta d Lib o sc Pa gu a Lim La M oq ue a o m ar c Ca ja na Cu sc Ta c ca sh 0 An Nuevos Soles 3000 as h us 05co 07 Ta 05 C aj cna 07 am 0 M arc 5-0 oq a 7 ue 05 gu -0 7 a Lo 05 re to 07 Pi 05ur a 07 Pa 05 sc -0 7 o Li 05-0 m 7 a 05 P La -0 u 7 Li no be 05 rt a -0 7 Ar d eq 05 ui pa 09 U H ua ca 050 nc ya av li 0 7 5 el ic -07 a Ju 0507 ní C n0 al 5la o 07 05 -0 I c 7 Tu a 0 m 5 Ay bes -07 ac 05 u Ap ch -07 ur o 0 im 5 ac -07 H M u ad án 05 -0 re u de co 0 7 Sa Dio 5-0 7 s n M 05 Am art -07 ín La azo 05 m ba nas 07 ye 0 5 qu -0 7 e 05 -0 7 C An c Conflicts per million inhabitants 05-07 Indice de conflictos 2005-2007 900 300 200 829 800 700 600 500 503 424 400 356 299 156 113 161 100 Source: Defensoría del Pueblo 2008 Compilation and graphic representation: The author 22 68 513 412 340 346 218 171 231 112 104 162 0 0 147 0 51 0 ca sh Ta C aj cna am M arc oq a ue gu a Pa sc o P La u Li no be rt a d Li m a C us Ar co eq ui pa Ju ní n H ua nc Ica av e Ap lica ur im Ay ac ac u H cho uá n Sa uc o n M ad M re art de ín Am Dio az s on as La P i m ba ura ye qu e C al la o Lo re U to ca y Tu ali m be s An Conflicts per million inhabitant 2007 Indice de conflictos 2007 Per capita conflict index aggregated 2007 700 615 600 500 400 300 303 200 100 236 130 278 136 134 179 39 9 Source: Defensoría del Pueblo 2008 Compilation and graphic representation: The author 40 29 24 48 74 116 52 0 8 40 44 0 28 57 0 0 Regressions of “canon minero” transfers and poverty on conflicts Per capita ACI Per capita ACI Per capita ACI Per capita ACI 2005-2007 (log) 2005 (log) 2006 (log) 2007 (log) “Canon minero”/capita (log) .34 (3.74)*** -.14 (-1.05) .45 (3.16)*** .60 (4.08)*** % Poverty .59 (6.58)*** .75 (5.44)*** .65 (4.58)*** .42 (2.86)*** R .66 .76 .76 .74 Adjusted R2 .42 .58 .57 .51 N 73 25 24 24 Dependent Variable OLS-regressions, standarised coeficients (t-values in parenthesis). *** significant at 1% level; ** significant at 5% level; * significant at 10% level. Conflicts, poverty and canon minero transfers Table 2. Evolution of correlation between “canon minero” transfers and conflicts 2005 2006 2007 Pearson Correlation -.16 .44* .65** N 25 25 25 Pearson Correlation between “canon minero” transfers/capita (log) and ACI/capita (log). ** Sig. (2-tailed) significant at 1% level; * Sig. (2-tailed) significant at 5% level. Table 3- Evolution of correlation between poverty and conflicts Pearson Correlation N 2005 2006 2007 .75** .61** .45* 25 24 24 Pearson Correlation between % Poverty and ACI/capita (log). ** Sig. (2-tailed) significant at 1% level; * Sig. (2-tailed) significant at 5% level. Correlation between conflicts and transfers 2005 Correlation between conflicts and transfers 2006 Correlation between conflicts and transfers 2007 Territorial conflicts in Moquegua