How I Define and Design This Course

advertisement

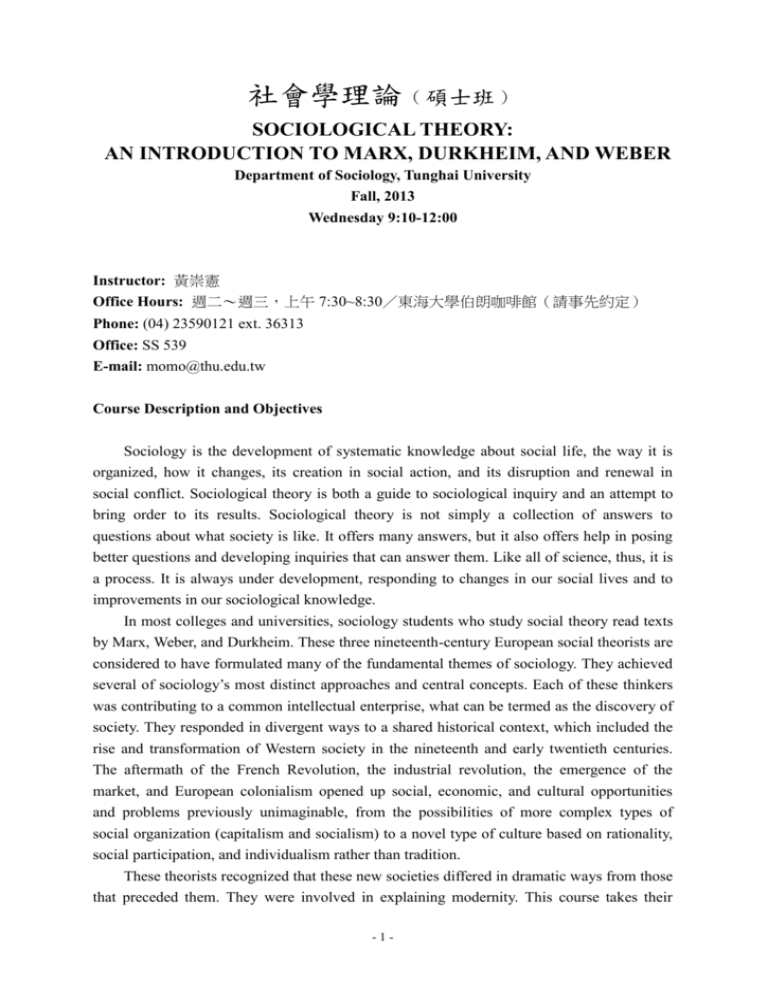

社會學理論﹙碩士班﹚ SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY: AN INTRODUCTION TO MARX, DURKHEIM, AND WEBER Department of Sociology, Tunghai University Fall, 2013 Wednesday 9:10-12:00 Instructor: 黃崇憲 Office Hours: 週二~週三,上午 7:30~8:30/東海大學伯朗咖啡館(請事先約定) Phone: (04) 23590121 ext. 36313 Office: SS 539 E-mail: momo@thu.edu.tw Course Description and Objectives Sociology is the development of systematic knowledge about social life, the way it is organized, how it changes, its creation in social action, and its disruption and renewal in social conflict. Sociological theory is both a guide to sociological inquiry and an attempt to bring order to its results. Sociological theory is not simply a collection of answers to questions about what society is like. It offers many answers, but it also offers help in posing better questions and developing inquiries that can answer them. Like all of science, thus, it is a process. It is always under development, responding to changes in our social lives and to improvements in our sociological knowledge. In most colleges and universities, sociology students who study social theory read texts by Marx, Weber, and Durkheim. These three nineteenth-century European social theorists are considered to have formulated many of the fundamental themes of sociology. They achieved several of sociology’s most distinct approaches and central concepts. Each of these thinkers was contributing to a common intellectual enterprise, what can be termed as the discovery of society. They responded in divergent ways to a shared historical context, which included the rise and transformation of Western society in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The aftermath of the French Revolution, the industrial revolution, the emergence of the market, and European colonialism opened up social, economic, and cultural opportunities and problems previously unimaginable, from the possibilities of more complex types of social organization (capitalism and socialism) to a novel type of culture based on rationality, social participation, and individualism rather than tradition. These theorists recognized that these new societies differed in dramatic ways from those that preceded them. They were involved in explaining modernity. This course takes their -1- works as the point of departure by engaging and summarizing the major themes of the classical sociological theory of Marx, Durkheim and Weber. Moreover, it also interprets their thought through the lens of new theoretical concerns that opened up new perspective on the issues in ways that not adequately addressed by Marx, Weber, and Durkheim. In doing so, this course is designed to familiar the students with classical sociological theory by focusing on the selected works of the “founding fathers”—Marx, Weber, and Durkheim—which are indispensable tools for us to grapple with fundamental questions about the rise of capitalism and the formations of modernity. Class Citizenship In a seminar course of this sort, it is my wish that I want the sessions and discussions to be as stimulating and exciting as possible, with a collegial and supportive atmosphere. Pedgogically, this seminar is dedicated to the proposition that knowledge is a collective product. This intellectual journey is intended to be collective; each participant (including me) is expected to contribute to our discussions and debates. Good seminars depend to a great extent on the seriousness of preparation by students. Let us all be good and responsible class citizens to make contributions as much as possible. Requirements and Grading: (More specific requirements/details will be announced in class) Class Participation and Discussion: 30% Weekly Issue Memos: 40% Handbook of Core Concepts: 30% The requirements for this course are fourfold. You must fulfill all four of them; do not take this course if for whatever reason you cannot do so. All participants will be expected to: 1) take an active part in discussions; 2) weekly issue memos; 3) a critical journal of core concepts. 1) Active Participation in Discussion: remember and apply this aphorism of Wittgenstein: “Even to have expressed a false thought boldly and clearly is already to have gained a great deal.” So speak up and speak out! What each of you will get out of the course depends in good measure on how much you collectively put in. So, play a constructive role in discussion: offer your own ideas in small chunks instead of long monologues; draw out and ask for clarification of the opinions of others; pose issues and questions you may not know the answer to; learn to permit someone to disagree with you without feeling attacked; learn to express disagreement in ways that promote constructive -2- discussion instead of polarization. 2) Weekly Issue Memo: to facilitate collective learning and avoid a situation of “pluralistic ignorance”, every week participants will submit issue-memo to the class as a whole by e-mail. I believe strongly that it is important for students to engage the week’s readings in written form prior to the seminar sessions. These weekly memos are intended to prepare the ground for good discussions by requiring participants to set out their initial responses to the readings which will improve the quality of the class discussion since students come to the sessions with an already thought-out agenda. Since this course is a required and foundational course, I particularly emphasize the preparation of this weekly issue memo as the core part of class training and will affect your final grade decisively. I refer to these written comments as “issue memos”. They are not meant to be mini-papers on the readings; nor need they summarize the readings as such. Rather, they are meant to be a think-piece, reflecting your own intellectual engagement with the material: specifying what is obscure or confusing in the reading; taking up issue with some core idea or argument; exploring some interesting ramification of an idea in the reading. These memos do not have to deal with the most profound, abstract or grandiose arguments in the readings; the point is that they should reflect what you find most engaging, exciting or puzzling. These memos are a real requirement, and failing to hand in memos will affect your grade. I will read through the memos to see if they are “serious”, but not grade them for “quality”. Since the point of this exercise is to enhance discussions, late memos will not be accepted. If you have to miss a seminar session for some reason, you are still required to prepare an issue memo for that session. Since I may not total the number of memos each student writes until the end of the semester, please keep copies to be sure of fulfilling the requirements. Students who submit memos should also be prepared to summarize/explain them in class. Please bring one copy of your issue memo to class to the instructor. 3) Keep a critical journal of core concepts (More specific instructions of preparing this journal will be discussed in due course of this class) Books Recommended for Purchase Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 中譯:簡惠美,1989, 《資本主義與現代社會理論:馬克思、涂爾幹、韋伯》 。台北:遠 流。 McLellan, David.著,王珍譯,2012,《馬克思》。台北:五南。 Marx, Karl. 2007. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. New York: Dover. Marx, Karl. 1998. The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition. London: Verso. -3- Eagleton, Terry. 2011. Why Marx Was Right. New Haven:Yale University Press 中譯:李尚遠,2012,《散步在華爾街的馬克思》。台北:商周。 Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: First Press. Weber, Max. 2001.The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. Weber, Max. 1949. The Methodology of the Social Sciences. New York: First Press. SEMINAR SESSIONS & READING ASSIGNMENTS PART I. KARL MARX (1818-1882): THE PRIMACY OF PRODUCTION PART II. Week 1. (09/11) Course Introduction Week 2. (09/18) Karl Marx (I) Week 3. (09/25) Karl Marx (II) Week 4. (10/02) 李猛演講 Week 5. (10/09) Karl Marx (III) Week 6. (10/16) Karl Marx (IV) EMILE DURKHEIM (1858-1917):THE DISCOVERY OF SOCIAL FACTS Week 7. (10/23) Durkheim (I) Week 8. (10/30) Durkheim (II) Week 9. (11/06) Durkheim (III) Week 10. (11/13) Midterm Exam (No Class) Week 11. (11/20) Durkheim (IV) PART III. MAX WEBER (1864-1920):THE PRIMACY OF SOCIAL ACTION Week 12. (11/27) Weber (I) Week 13. (12/4) Weber (II) Week 14. (12/11) Weber (III) Week 15. (12/18) Weber (IV) Week 16. (12/25) 聖誕節放假 Week 17. (01/01) 元旦放假 Week 18. (01/08) Final Exam (No Class) -4- Week 1 (9/11) Introduction (No Required Readings for This Week; Listed Readings for Suggestions Only) How I Define and Design This Course Dilemma: Breadth or Depth? (Brain-storming and Any Suggestions Welcome!) Language Issues Theory as Tool and Theory as End-Product The Rise and Fall of Classical Social Theory Conceptual Pragmatism Learning about vs. Learning from Social Theory Theoretical Understanding vs. Theorization Consuming vs. Constructing Theory Text vs. Context of Social Theory: History of Ideas or Sociology of Knowledge? * Critical Issues in Social Theory Holism vs. Methodological Individualism Structure vs. Agency Level of Abstraction vs. Unit of Analysis Positivism vs. Anti-Positivism: The Philosophy of Science Debate Explanation vs. Interpretation Forms of Explanation: Causal, Functional, Intentional Meta-theoretical vs. Substantive Conceptualization vs. Labeling (or Renaming) The Types of Sociological Theorizing Nature of Constitutive Elements Subjective Terms of Individualistic Explanation Holistic Objective Constructionism Weber Utilitarianism Marshall, Pareto Functionalism Durkheim Critical -5- Structuralism Marx A Mapping of Some Sociological Theories in a Two-Dimensional Space Action Structure Subjectivism Symbolic Interactionalism Phenomenology Weber Ethnomethodology Objectivism Homans Giddens Berger/Louckmann Bourdieu Marx Durkheim * The Core Concepts That Sociological Theory Must Address and Attempt to Reconcile: Agency – Meaning and Motives in Social Arrangements Rationality – The Maximization of Individual Interest Structure – Secret Patterns Which Determine Experience System – An Overarching Order * The Main Phenomenon That Sociological Theory Seeks to Explain: Culture and Ideology Power and the State Differentiation and Stratification Sociology at Large Background Readings: Bauman, Zygmunt, and Tim May. 2001. Thinking Sociologically. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. Johnson, Allan G.. 1997. The Forest and the Trees: Sociology as Life, Practice, and -6- Promise. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Giddens, Anthony. 1982. Sociology: A Brief but Critical Introduction. London: Macmillan Press. Core Readings: Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Suggested Readings: Halliday Terence, and Morris Janowitz, eds. 1992. Sociology and Its Publics: The Forms and Fate of Disciplinary Organization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * The Rise of Social Theory Hamilton, Peter. 1992. “The Enlightenment and the Birth of Social Science.” Pp. 17-58 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. Heilbron, Johan. 1995. The Rise of Social Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Hughes, H. Stuart. 1981. 《意識與社會:1890 年至 1930 年間歐洲社會思想的新取向》。 李豐斌譯。台北:聯經。 Marsh, David & Gerry Stoker, 2002. Theory and Methods in Political Science. New York :Palgrave Macmillan ---中譯, 2007/《政治學方法論與途徑》. 台北:韋伯文化。(第一章 政治學中的本體論 與知識論) * Political Formations of Modernity Held, David. 1992. “The Development of the Modern State.” Pp. 71-119 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. * Economic Formations of Modernity Brown, Vivienne. 1992. “The Emergence of the Economy.” Pp. 127-166 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. * Social Formations of Modernity Bradley, Harriet. 1992. “Changing Social Structures: Class and Gender.” Pp. 177-211 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. -7- * Cultural Formations of Modernity Bocock, Robert. 1992. “The Cultural Formations of Modernity.” Pp. 229-268 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. * The West and the Rest Hall, Stuart. 1992. “The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power.” Pp. 275-320 in Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity. * Why Classical Sociological Theory? Background Readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Craib, Ira. 1997. Classical Social Theory. 1997. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Callinicos, Alex. 1999. Social theory :a historical introduction . New York :New York University Press ---中譯 2000.《社會學理論思想的流變》。簡守邦譯。臺北:韋伯文化. Aron, Raymond. 1967. Main currents in sociological thought. translated by Richard Howard & Helen Weaver. New York:Basic Books, ----中譯. 社會學主要思潮 葛智強,胡秉誠,王滬寧譯 。上海:上海譯文出版社。 Core Readings: Merton, Robert. 1967. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press. Pp. 1-38. Alexander, Jeffrey. 1987. “The Centrality of the Classics.” Pp. 11-57 in Social Theory Today, edited by Anthony Giddens & Jonathan Turner. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Suggested Readings: Alexander, Jeffrey. 1982-3. Theoretical Logic in Sociology. 4 vols. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Levine, Donald. 1995. Visions of the Sociological Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Holton, Robert. 1996. “Classical Social Theory.” Pp. 25-52 in The Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, edited by Bryan Turner. Oxford UK & Cambridge USA: Blackwell -8- PART I: KARL MARX(1818-82): THE PRIMACY OF PRODUCTION Driving Impulses Key Issues: A Materialist Social Ontology Historical Materialism Critique of Capitalism Class as a Social Relation The State and Politics Seeing Things Differently Legacies and Unfinished Business Background Readings: Althusser, Louis, and Etienne Balibar. 1970. Reading Capital. London: NLB. Anderson, Perry. 1976. Considerations on Western Marxism. London: NLB. ----. 1983. In the Tracks of Historical Materialism. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. Elster, Jon. 1986. An Introduction to Karl Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gouldner, Alvin. 1980. The Two Marxism: Contradictions and Anomalies in the Development of Theory. New York: Seabury Press. McLellan. David. 1974. Karl Marx: His Life and Thought. Basingstoke: Macmillan. Mandel, Ernest. 1970. Marxist Economic Theory. New York: Monthly Review Press. General Analyses of Marx’s Works Avineri, Shlomo. 1968. The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Berlin, Isaiah. 1996. Karl Marx: His Life and Work. New York: Oxford University Press. Carver, Terrell, ed. 1993. The Cambridge Companion to Marx. New York: Cambridge University Press. Cohen, G. A. 1978. Karl Marx’s Theory of History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Giddens, Anthony. 1981. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, vol. 1: Power, Property and the State. Berkeley: University of California Press. Giddens, Anthony. 1985. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, vol. 2: The Nation-State and Violence. Berkeley: University of California Press. McLellan, David. 1972. The Thought of Karl Marx: An Introduction. New York: Harper and Row. Ollman, Bertell. 1977. Alienation: Marx’s Concept of Man in Capitalist Society. New -9- York: Cambridge University Press. West, Cornel. 1991. The Ethical Dimensions of Marx’s Thought. New York: Monthly Review Press. Philosophical Aspects of Marx’s Thought Althusser, Louis. 1970. For Marx. New York: Pantheon Books. Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Spectres of Marx. New York: Routledge. Kolakowski, Leszek. 1978. Main Currents of Marxism: Its Rise, Growth, and Dissolution. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Lefebvre, Henri. 1982. The Sociology of Marx. New York: Columbia University Press. Marxist Economics Mandel, Ernest. 1971. The Formation of the Economic Thought of Karl Marx, 1843 to Capital. New York: Monthly Review Press. Moseley, Fred. ed. 1993. Marx’s Method in Capital: A Reexamination. Atantic Highlands, NJ: Prometheus Books. Sweezy, Paul. 1970. The Theory of Capitalist Development: Principles of Marxian Political Economy. New York: Modern Reader Paperback. Suggested Readings: Elster, Jon. 1985. Making Sense of Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Harvey, David. 1982. The Limits to Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Postone, Moishe. 1997. “Rethinking Marx (in a Post-Marxist World).” Pp. 11-44 in Reclaiming the Sociological Classics: The State of the Scholarship, edited by Charles Camic. Oxford: Blackwell. Wright, Erik. 1996. “Marxism after Communism.” Pp. 121-145 in Social Theory & Sociology: The Classics and Beyond, edited by Stephen P. Turner. Oxford: Blackwell. Collections of Marx/Engels’ Works Tucker, Robert. 1972. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: Norton. McLellan. David, ed. 1977. Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Elster, Jon. ed. Karl Marx: A Reader. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Week 2 (9/18) Karl Marx (I) Background Readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings - 10 - of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xi-xvi, 1-34 Core Readings: McLellan, David.著,王珍譯,2012,《馬克思》。台北:五南。頁 21-249。 Week 3 (9/25) Karl Marx (II) Background Readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xi-xvi, 35-64 Core Readings: McLellan, David.著,王珍譯,2012,《馬克思》。台北:五南。頁 251-505。 Week 4 (10/02) 李猛演講 Week 5(10/09) Karl Marx (III) Core Readings: Marx, Karl. 1998. The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition. London: Verso. Week 6 (10/16) Karl Marx (IV) Core Readings: Terry Eagleton 著,李尚遠譯,2012,《散步在華爾街的馬克思》。台北:商周。 PART II: EMILE DURKHEIM (1858-1917): THE DISCOVERY OF SOCIAL FACTS Driving Impulses Key Issues: Legitimating the Discipline: Sociology, Science, and Emergence The Relationship between the Individual and Society: Images of Society Three Studies of Social Solidarity The Division of Labor in Society Suicide The Elementary Form of the Religious Life Seeing Things Differently Legacies and Unfinished Business Background Readings: Lukes, Stephen. 1985. Emile Durkheim: His Life and Work: A Historical and Critical - 11 - Study. Stanford: Stanford University Press. *This book remains the most complete study of Durkheim. Alexander, Jeffrey. 1982. The Antinomies of Classical Thought: Marx and Durkheim. Berkeley: University of California Press. Cladis, Mark. 1992. A Communitarian Defense of Liberalism: Emile Durkheim and Contemporary Social Theory. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Joas, Hans. 1993. “Durkheim and Pragmatism: The Psychology of Consciousness and the Social Constitution of Categories” pp. 55-78 in Pragmatism and Social Theory by Hans Joas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Goffman, Erving. 1967. Interaction Ritual. Garden City: Anchor Books. General Analyses of Durkheim’s Works Giddens, Anthony. 1979. Emile Durkheim. New York: Viking Press. Lehmann, Jennifer. 1994. Durkheim and Women. Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press. Miller, William Watts. 1996. Durkheim, Morals, and Modernity. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. Nisbet, Robert, ed. 1965. Emile Durkheim. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Parkin, Frank. 1992. Durkheim. New York: Oxford University Press. Pearce, Frank. 1989. The Radical Durkheim. London: Unwin Hyman. Pickering, W. S. F. ed. 2001. Emile Durkheim: Critical Assessments, 4 vols. New York: Routledge. Poggi, Gianfrance. 2000. Durkheim. New York: Oxford University Press. Turner, Stephen, ed. 1993. Emile Durkheim: Sociologists and Moralists. New York: Routledge. The Philosophical Dimensions of Durkheim’s Thought Jones, Robert Alun. 1999. The Development of Durkheim’s Social Realism. New York: Cambridge University Press. LaCapra, Dominick. 1972. Emile Durkheim: Sociologist and Philosopher. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Durkheim and Religion Allen, N. J., W. S. F. Pickering and W. Watts Miller, eds. 1998. On Durkheim’s Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. New York: Routledge. Durkheim and the Law Cotterell, Roger. 1999. Emile Durkheim: Law in a Moral Domain. Stanford: Stanford University Press. - 12 - Suggested Readings: Jones, Robert Alun. 1994. “Ambivalent Cartesians: Durkheim, Montesquieu, and Method.” American Journal of Sociology 100(1): 1-39. Gane, Mike. 1988. On Durkheim’s Rules of Sociological Method. London and New York: Routledge. Alexander, Jeffrey. 1988. Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wuthnow, Robert. 1987. Meaning and Moral Order: Explorations in Cultural Analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press. Week 7(10/23) Durkheim (I) Background Readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp.65-118 Core Readings: Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: Free Press. Pp.31-49 Week 8 (10/30) Durkheim (II) Core Readings: Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: First Press. Pp.50-84 Week9 (11/06) Durkheim (III) Core Readings: Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: First Press. Pp.85-118 Week 10 (11/13) Mid-term exam (No-Class) Week 11 (11/20) Durkheim (IV) Core Readings: Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: First Press. Pp.119-146 PART III: MAX WEBER (1864-1920): THE PRIMACY OF SOCIAL ACTION - 13 - Driving Impulses: Life and Orientation Key issues: On the Relationship between Religion and Economics The Disenchantment of the World and the Rationalization of Life Method and the Philosophy of Science Authority or “Legitimate Domination” Seeing Things Differently Weberian Legacies Background Readings: Bendix, Reinhard. 1962. Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. New York: Doubleday Anchor. Collins, Randall. 1981. “Weber’s Last Theory of Capitalism: A Systematization.” American Sociological Review 45 (6): 925-42. Freund, Julien. 1968. The Sociology of Max Weber. New York: Pantheon Books. Kasler, Dirk. 1988. Max Weber: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Brubaker, Roger. 1984. Limits of Rationality: An Essay on the Social and Moral Thought of Max Weber. London: Allen and Unwin. Mommsen, Wolfagang. 1974. The Age of Bureaucracy: Perspectives on the Political Sociology of Max Weber. Oxford: Blackwell. Gerth, H.H, and C. Wright Mills. 1958. “Introduction.” Pp. 1-74 in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. New York: Oxford University Press. Weber, Marianne. 1974. Max Weber. New York: Wiley Press. General Analyses of Weber’s Works Diggins, John P. 1996. Max Weber: Politics and the Spirit of Tragedy. New York: Basic Books. Hennis, Willaim. 1988. Max Weber: Essays in Reconstruction. Boston: Allen and Unwin. Kalberg, Stephen. 1994. Max Weber’s Comparative-Historical Sociology. ----. 1997. “Max Weber’s Sociology: Research Strategies and Modes of Analysis.” Pp. 208-241 in Reclaiming the Sociological Classics: The State of the Scholarship, edited by Charles Camic. Oxford: Blackwell. Scaff, Lawrence. 1989. Fleeing the Iron Cage: Culture, Politics and Modernity in the Thought of Max Weber. Berkeley: University of California Press. Sica, Alan. 1988. Weber, Irrationality, and Social Order. Berkeley: University of California Press. - 14 - Turner, Bryan. 1995. For Weber: Essays on the Sociology of Fate. London: Sage. Turner, Stephen, ed. 2000. The Cambridge Companion to Weber. New York: Cambridge University Press. Weber on Politics Beetham, David. 1997. Max Weber and the Theory of Modern Politics. New York: Polity Press. Breiner, Peter. 1996. Max Weber and Democratic Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Mommsen, Wolfgang. 1992. Max Weber and German Politics: 1890-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Weber on Methodology Ringer, Fritz. 2000. Max Weber’s Methodology: The Unification of the Cultural and Social Sciences. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Weber on Economics Swedberg, Richard. 1998. Max Weber and the Idea of Economic Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Weber on Religion Huff, Toby and Wolfgang Schluchter, eds. 1999. Max Weber and Islam. New Brunswick, N. J.: Transaction Publishers. Turner, Bryan. 1974. Weber and Islam. New York: Routledge. Suggested Readings: Alexander, Jeffrey. 1983. The Classical Attempt at Theoretical Synthesis: Max Weber. Berkeley: University of California Press. Collins, Randall. 1986. Weberian Sociological Theory. London: Cambridge University Press. Lehman, Hartmunt, and Guenther Roth, eds. 1987. Weber’s Protestant Ethic: Origins, Evidence, Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Poggi, Gianfranco. 1983. Calvinism and the Capitalist Spirit: Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. Mommsen, Wolfgang. 1989. The Political and Social Theory of Max Weber. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Schluchter, Wolfgang. 1979. Rationalism, Religion, and Domination: A Weberian Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press. - 15 - Week 12 (11/27) Weber (I) Background readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp.119-144 Core Readings: Weber, Max. 2001.The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. Pp.1-38 Week 13(12/4) Weber (II) Background readings: Giddens, Anthony. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp.145-184 Core Readings: Weber, Max. 2001.The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. Pp. 100 (Started at the paragraph. ‘It is our task…’)-125 Week 14 (12/11) Weber (III) Core Readings: Weber, Max. 1994. “ Objectivity in Social Science and Social Policy”, Pp.49-112 from The Methodology of The Social Sciences. New York: Free Press. Week 15 (12/18) Weber (IV): Core Readings: Weber, Max. 2009. “Politics as a Vocation.” Pp.77-128From From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. . New York: Routledge. Week 16 (12/25): 聖誕節放假 Week 17 (01/1): 元旦放假 Week 18 (1/16) Final Exam (No Class) - 16 -