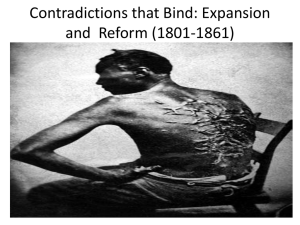

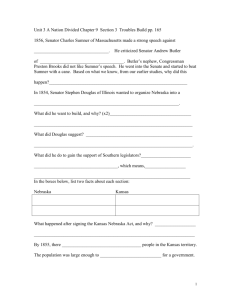

Bloody Kansas - alexandriaesl

advertisement