Definitions (Powerpoint)

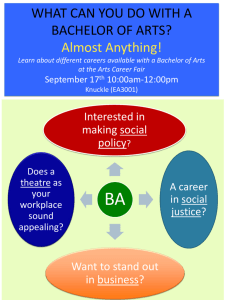

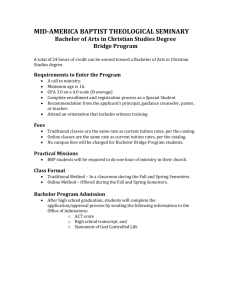

advertisement

Definitions

CONNOTATION AND DENOTATION

Connotation and Denotation

So far we’ve looked at two theories of meaning–

the Idea Theory and Verificationism. In both

theories there are two aspects to meaning,

which we might call connotation and

denotation.

Connotation

Connotation corresponds more closely with the

ordinary English sense of the word ‘meaning’:

on the Idea Theory, for instance, the ‘meaning’

or connotation of a word is an idea. The word

‘dog’ has as its meaning the idea of a dog.

Denotation

But there’s another sense in which the word

‘dog’ means dogs (those furry smelly barking

things): it applies to dogs and it’s true of dogs

(and false of everything else).

Denotation involves the relation between words

and the world– what words apply to/ are true

of.

Relation between the Two

The two aspects of meaning are not unrelated.

The Idea Theory’s theory of connotation (words

connote ideas) explains why words have the

denotations they do (they denote what the

ideas resemble). So ‘dog’ is true of dogs because

‘dog’ connotes the idea of a dog, and dogs

resemble the idea of a dog.

Verificationism

Verificationism has a similar structure: words

mean (connote) sets of possible experiences,

and are true of the things those experiences

verify. ‘There is a dog’ is true when there is a

dog, because it connotes the experiences {I hear

barking, I see a furry thing, the furry thing

smells}, and when I have those experiences,

there is a dog.

Structure of a Theory of Meaning

Here’s the structure of the theories we’ve

considered so far:

• Words are arbitrarily and conventionally

associated with connotations.

• Connotations plus a certain relation

(resemblance, verification) determine

denotations.

A particular theory says what the connotations

are, and what the certain relation is.

DEFINITIONS

“The Definition Theory”

According to “the Definition Theory” the

connotation of a word is a definition, and the

denotation of the word is what the definition is

true of.

Circularity

I say “the Definition Theory” in quote-marks

because no one actually holds the theory in any

sort of general form (with one exception we’ll

consider later).

The principal problem with a generalized

definition theory is that it’s circular.

Generalized Definition Theory

By “a generalized definition theory” I mean a

theory according to which every expression has

a definition as its meaning, including all the

expressions that show up in the definition. So if

‘bachelor’ := unmarried man

Then ‘unmarried’ and ‘man’ will also have

definitions as their meanings.

Circularity

Here’s the sense in which a generalized

definition theory is circular:

Let’s say x defines y

If, and only if

x is in the definition of y or x is in the definition

of a word that defines y

Then for any finite set of words, all of which

have definitions, some word w defines w.

Problem with Circularity

The problem with circularity is that it trivializes

the claims of the Definition Theory. If I want to

know what a word is true of by learning its

definition, I have to know what the words that

define it are true of. But for some word w, w

defines w. So in order to learn what w is true of,

I have to already know what w is true of. It

doesn’t help to remove w, because it follows by

the same logic that the language with w

removed is also circular.

Dictionaries and Circularity

This is why you can’t learn a foreign language–

say Kalaallisut– merely from a dictionary where

Kalaallisut terms are defined by other Kalaallisut

terms. When you look up a word all you get are

a bunch of words you don’t know. When you

look up those words, the same thing happens.

And it never ends, because eventually the

definitions start sending you in circles.

The Attraction of Definitions

There’s something that’s very attractive about

the Definition Theory, even if it can’t be

generalized. If you ask somebody, “What does

‘defenestrate’ mean?” what they give you is a

definition. You can find the meanings of words

in dictionaries– that is, you can find definitions

there. Giving, finding out, and knowing

meanings seems to involve definitions.

Particular Definition Theories

The way to go then is to adopt a particular

definition theory. On such an account, not every

word has a definition for its meaning, only some

particular subclass of all the words. The

undefined words are the primitive vocabulary.

Everything else is defined in terms of the

primitive vocabulary, or defined in terms of

things that are defined in terms of the primitive

vocabulary, or… etc.

Hybrid Theory of Meaning

Adopting a particular definition theory requires

that you also adopt a separate theory of

meaning to explain what the primitive

vocabulary means. For example, in the Carnap

reading ‘x is an arthropod’ had a definition for a

meaning. It was defined by logical operations on

protocol sentences. Protocol sentences had no

definitions: their meaning was their verification

conditions.

Important Point

This means that understanding a word cannot in

general be the same thing as knowing its

definition. Only understanding non-primitive

vocabulary involves knowing definitions, since

the primitive vocabulary does not have any

definitions.

Explanatory Virtues of Definitions

If you found out that all people with large ears

were rich and that only people with large ears

were rich, that would be interesting, and would

call out for investigation.

However, it’s not interesting that all and only

bachelors are unmarried men, and we don’t

need an investigation to determine that they are

or why they are.

Explanatory Virtues of Definitions

Definitions can explain this difference. Anyone

who knows what ‘bachelor’ means knows the

definition of ‘bachelor’ (because this is the

meaning) and hence knows that bachelors are

unmarried men. This is why it’s not interesting,

and why you don’t need to survey the bachelors

to find out if they’re unmarried. You know in

advance of a survey, by knowing what bachelor

means, that is, its definition.

Definitions and Informal Validity

Definitions can also help us explain informal

validity. A formally valid argument is one where

the conclusion follows from the premises, no

matter what the non-logical expressions mean:

Mimi is orange & Mimi is a cat.

Therefore, Mimi is orange.

Definitions and Informal Validity

Definitions can also help us explain informal

validity. A formally valid argument is one where

the conclusion follows from the premises, no

matter what the non-logical expressions mean:

x is F & x is G.

Therefore, x is F.

Definitions and Informal Validity

But you seemingly can’t explain some

(intuitively valid) inferences in the same way. We

can call these ‘informally valid’ inferences:

Fred is a bachelor

Therefore, Fred is unmarried

Definitions and Informal Validity

But you seemingly can’t explain some

(intuitively valid) inferences in the same way. We

can call these ‘informally valid’ inferences:

x is H

Therefore, x is F

Some inferences like this are not valid.

Definitions and Informal Validity

However, if “Fred is a bachelor” really means

“Fred is unmarried & Fred is a man,” then

informal validity simply becomes formal validity:

Fred is unmarried & Fred is a man.

Therefore, Fred is unmarried.

Definitions and Informal Validity

However, if “Fred is a bachelor” really means

“Fred is unmarried & Fred is a man,” then

informal validity simply becomes formal validity:

x is F & x is G.

Therefore, x is F.

All inferences of this form are valid.

Definitions and Understanding

Even though we require a separate theory of

understanding for the primitive vocabulary, it

might be thought that definitions help explain

what it is to understand at least some

expressions. To understand the definable (nonprimitive) expressions in a sentence is to

retrieve their definitions from memory. That

doesn’t solve the general problem of

understanding, but it’s a good first step.

Definitions and Concept Acquisition

Fodor (1975) argues that you cannot learn basic

concepts, they have to be innate. Suppose COW

is a basic concept. To learn that ‘cow’ means

COW involves (i) hypothesizing that ‘cow’ means

COW (ii) testing that hypothesis against the

linguistic evidence and (iii) having the

hypothesis confirmed by the evidence. This

means that to learn what ‘cow’ means, you must

be able to hypothesize (think) it means COW,

and so you must already possess COW.

Virtues of Definitions

• Definitions explain how we know facts like all

bachelors are unmarried, and why they’re true.

• Definitions explain informal validity by reducing it

to formal validity.

• Definitions provide a model of non-primitive

word understanding.

• Definitions explain how it is we can acquire new

concepts: we construct them out of old ones.

Definitions and Concept Acquisition

Well, it’s likely we have some innate concepts,

like CAUSE, and UP, and MAMA, and HUNGER.

But surely the concepts CARBURETOR, and

SUSHI, and NEPTUNE, and QUARK are acquired

sometime after birth. If Fodor’s argument is

right, they must be complex concepts. The

reason we can learn, say, CARBURETOR, is that

it’s defined out of other concepts, which were

either innate or defined out of other concepts…

Lexicalism

As natural as the Definition Theory seems, many

philosophers have argued that there are fewer

definitions than we might think, and maybe

almost none at all. They hypothesis that most

words don’t have definitions in terms of other

words is called Lexicalism (because it says that

the primitive terms = the lexical items, i.e. the

words).

AGAINST DEFINITIONS

The Problem of Examples

Philosophers are fond of ‘bachelors are

unmarried men.’ Why? Because it’s really hard

to find examples of definitions that work– where

the defining part means the same thing as the

defined part. ‘Bachelor’ isn’t even obvious (is

the pope a bachelor? Are 14 year-olds?). Kinship

terms and animal terms are about the only good

bets.

Kinship Terms

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Sister:= female sibling

Brother:= male sibling

Mother:= female parent

Father:= male parent

Grandmother:= female parent of parent

Uncle:= sibling of parent

Cousin:= child of sibling of parent

Animal Terms

We often have words for male-X, female-X,

young-X, group-of-X, and meat-of-X:

• Boar := male pig

• Sow := female pig

• Piglet := young pig

• Drift := group of pigs

• Pork := meat of pigs

Historically Unsuccessful

That’s not very much to build an entire theory

off of. Proponents of definitions have tried to

find lots of other examples, but historically the

project hasn’t been very successful. One

example involves causative verbs: sink, boil,

break, open, etc.

Causative/ Anti-causative

1a. The ship sank.

1b. The pirates sank the ship.

2a. The water boiled.

2b. The chef boiled the water.

3a. The glass broke.

3b. The child broke the glass.

4a. The door opened.

4b. The actor opened the door.

The Causative Analysis

The idea here is that the causative “sink” is

defined by the anti-causative “sink” + “cause”:

“The pirates sank the ship” := The pirates caused

the ship to sink.

Furthermore, maybe even some words that

don’t alternate are similar: “kill” = “cause to

die.”

Problems with the Analysis

In a classic paper called “Three Reasons for Not

Deriving ‘Kill’ from ‘Cause to Die,’” (1970) Fodor

presents three reasons for rejecting this

analysis.

First, Fodor argues that ‘die’ should not be

handled in the same way as ‘sink.’

Distribution of Causitives

5a. The pirates caused the boat to sink, and I’m

surprised they did.

5b. The pirates caused the boat to sink, and I’m

surprised it did.

6a. The pirates sank the boat, and I’m surprised

they did.

6b. The pirates sank the boat, and I’m surprised

it did.

‘Kill’ vs. ‘Cause to Die’

7a. John caused Mary to die, and I’m surprised

he did.

7b. John caused Mary to die, and I’m surprised

she did.

8a. John killed Mary, and I’m surprised he did.

#8b. John killed Mary, and I’m surprised she did.

More Problems

So ‘kill’ doesn’t pattern like ‘cause to die.’ Still, it

looks like causative ‘sink’ does pattern with

‘cause to sink’, so can we keep that part of the

analysis? Fodor argues ‘no’ again.

“You Melt It When It Melts”

9a. Floyd caused the glass to melt on Sunday by

heating it on Saturday.

#9b. Floyd melted the glass on Sunday by

heating it on Saturday.

“one can cause an event by doing something at

a time which is distinct from the time of the

event. But if you melt something, then you melt

it when it melts.” (p. 433)

Fodor’s Final Argument

10a. John caused Bill to die by swallowing his

tongue. [Ambiguous]

10b. John killed Bill by swallowing his tongue.

[Only the silly reading]

Causation Not Direct Enough

The point isn’t that there is only one clause to

modify in the 10b example. Suppose I’m driving

down the street and a clown runs in front of me,

waving his arms. Being distracted, I drive into a

tree:

TRUE: The clown caused my car to crash.

FALSE: The clown crashed my car.

The Problem of Examples

There aren’t many good candidates for (good)

definitions. Most dictionary “definitions” are no

such thing.

A Semantic Limerick

“There existed an adult male person who had

lived a relatively short time, belonging or

pertaining to St. John’s, who desired to commit

sodomy with the large web-footed swimmingbirds of the genus Cygnus or subfamily Cygninae

of the family Anatidae, characterized by a long

and gracefully curved neck and a majestic

motion when swimming.

A Semantic Limerick

“So he moved into the presence of the person

employed to carry burdens, who declared: “Hold

or possess as something at your disposal my

female child! The large web-footed swimming

birds of the genus Cygnus or subfamily Cygninae

of the family Anatidae, characterized by a long

and gracefully curved neck and a majestic

motion when swimming, are set apart, specially

retained for the Head, Fellows and Tutors of the

College.”

The Joke

There once was a lad from St. John’s

Who wanted to bugger some swans

So he went to the porter

Who said, “Take my daughter,

The swans are reserved for the Dons!”

Informal Validity Again

Before I suggested that definitions might help

reduce informal validity to formal validity. So if

“John is a bachelor” just means “John is

unmarried and John is a man” then the

seemingly informal inference from “John is a

bachelor” to “John is unmarried” is actually

formally valid (conjunction elimination).

“bachelor” → “unmarried” works because

bachelor = unmarried + X.

Informal Validity Again

However, Fodor et al. suggest that this can’t

work in general. Consider the inference:

This is red, therefore this is colored.

Notoriously, red ≠ colored + X, for any X. So this

isn’t an inference of the form: colored + X →

colored.

Definitions and Understanding Again

Another virtue of definitions is that they’re

supposed to provide a model for how we

understand the non-primitive vocabulary: by

retrieving its definition from memory. Fodor et

al. argue on empirical grounds that it’s simply

implausible that definitions are retrieved from

memory when sentences involving supposedly

“defined” terms are understood.

Empirical Research

Here’s the sort of anti-definition research Fodor

et al. adduce. It’s a robust finding in psychology

that inferences involving negatives take longer

to perform than inferences involving only

positives. If I give you two squares, one of which

is red and the other of which is green, you’ll be

quicker at pointing to the correct one when

asked “Which is red?” than you would be if

asked “Which is not green?”

Empirical Research

Therefore, we expect that if bachelor is

processed as NOT-married man, it should show

the same inferential lag as complex symbols

with overt negations. Fodor, Fodor, and Garrett

(1977) “The psychological unreality of semantic

representations” found just that. It should be

noted that Fodor et al. (1980) describe this

evidence as “rather tentative.”

Empirical Research

I am not claiming that we have particularly good

evidence against the involvement of definitions

in language processing. I am not a psychologist

and I haven’t kept up on the research on

definitions since 1980. What’s valuable in Fodor

et al.’s argument is that it makes clear that

certain questions (like this one) in the

philosophy of language are amenable to

empirical treatment and are thus in some ways

outside the scope of philosophical practice.

Understanding: Final Point

We know from the vicious circularity argument

that some terms we understand (the primitive

vocabulary) must be undefined. By hypothesis

we understand these terms, so we know that

understanding without definitions is possible.

Thus in a sense definitions are superfluous in an

account of understanding. If furthermore there’s

empirical evidence that they actually don’t play

a psychological role, that’s pretty damning.

Concept Acquisition

Definitions also provided an explanation of how

we can acquire new concepts on the hypothesis

formation and confirmation model of learning.

On this model, learning happens by proposing a

hypothesis, testing it, and accepting it if it’s

confirmed or rejecting it otherwise. The

problem is that if you don’t already have the

concept, e.g., BACHELOR, you can’t propose the

hypothesis ‘bachelor’ means BACHELOR, and

hence can’t ever learn what ‘bachelor’ means.

Definitions and Concept Acquisition

However, if you already understand UNMARRIED

and MAN, then you can propose the hypothesis

‘bachelor’ means UNMARRIED MAN and if

‘bachelor’ really does mean that (because that’s

the definition of ‘bachelor’) then presumably

you can learn it. Definitions to the rescue!

The Lexicalist Response

Fodor at least has a strange response. Yes, that’s

one way to go, he would say. But, alternatively,

it’s also possible to accept the consequence that

no simple English expression is learnable, and

that all the concepts that correspond to them

(like BACHELOR and CARBURETOR) are innate–

we’re born with these concepts! Most

philosophers think Fodor is a little bit crazy for

endorsing the second option.

More Plausible Routes?

Oved (2009) suggests that we can use

descriptions that are not definitions to latch

onto certain properties that we otherwise can’t

represent. Once latched onto, we can introduce

new concepts that have the content in question.

So for example, you might use “Granny’s favorite

color” to think about redness, and then

introduce a new concept RED to represent

redness– even though ‘red’ can’t be defined as

“Granny’s favorite color” (not co-intensional).

Where We Stand

• Definitions can’t explain how all words get

their meaning. Since another explanation is

needed, they’re slightly superfluous.

• Definitions can’t explain all informal validity.

Since another explanation is needed, they’re

slightly superfluous.

• Definitions can’t explain all word

understanding. Since another explanation is

needed, they’re slightly superfluous

Where We Stand

• Furthermore, there are only a handful of really

plausible examples of possible definitions.

• Thus, if we accept that some primitive terms

are learned, then definitions can’t explain all

concept acquisition. Since another

explanation is needed, they’re slightly

superfluous.

• This is beginning to suggest that definitions

are superfluous.

Definitions and the A Priori

However, there is one other virtue of definitions

we’ve thus far neglected. Definitions explain

how we know without investigation that all

bachelors are unmarried men. In order to know

what “bachelor” means, you have to know its

definition. It is defined as “unmarried man,”

therefore anyone who knows what “bachelor”

means knows that bachelors are unmarried

men. This requires no investigation into the

marital status of bachelors.

However, many philosophers have become

disenchanted with the idea that there are things

that are true “in virtue of meaning” (analytic

truths). This is partly due to the Quine paper we

talked about last time, “Two Dogmas of

Empiricism.” Remember that Quine’s central

point was that confirmation is theory-relative.

The Web of Belief

Quine’s picture is that our beliefs form a “web”

where change in the degree of belief in any

statement affects the degrees of belief in all of the

others, simultaneously. Some statements are more

toward the “periphery” of the web (observation

statements), and they are more likely to change

with changing experience. But sometimes

“recalcitrant” experience causes us not to revise the

periphery, but the more central, deeply theoretical

(and even logical) statements.

Nothing is Safe

On this model, no belief is immune from

revision. If experience seemingly disconfirms

even logical truths, and it does it persistently

enough (“recalcitrant experience”) then

eventually you’ll have to accept the experience

and reject the logical truths. That’s the model.

Quine vs. Definitions

If you accept the model, then definitions are too

strong of an explanation for how we know that

all and only bachelors are unmarried. Because if

that’s a simple matter of definition, then no

experience should lead us to reject the claim

that bachelors are unmarried. But our model is

that any claim can be rejected when faced with

recalcitrant experience.

One Dogma

(In fact, that was the first “dogma of

empiricism”: that there were analytic truths–

things that were true in virtue of what they

meant.)

THE ABSURDITY OF FIT

The Absurdity of Fit

In one sense, all the views we’ve considered in

class so far are views on which meaning is a type

of “fit.” On the idea theory, meanings

(connotations) are ideas. Ideas have a certain

pre-existing structure: just as in a painting the

different parts are related to one another, and

colored in various ways, and so forth.

Idea Theory and Fit

In order to find out what an idea represents, we

go out and find the things that best fit the idea,

that most closely match its pre-existing

structure, that best resemble it. Whatever best

fits the pre-existing structure is what the idea

represents.

Verificationism and Fit

While verificationism doesn’t have the same

“little colored pictures” view of ideas or the

resemblance theory of representation, it too

involves a type of fit. In advance, words are

associated with specific experiences that are

stipulated to verify them. Why does a certain

experience verify “That is red”? Because we said

so, that’s why. We say in advance what

experiences verify which sentences, then we go

look and see what experiences we have.

Definitions and Fit

Similarly, a definitions view is a type of fit as

well. We say in advance what the definitions of

words are. You don’t discover that bachelors are

unmarried, you sit down and make it true by

fiat.

The Absurdity of Fit

But there’s something terribly wrong with the

idea that meanings are specified in advance of

our encounters with the world. That before any

experience of the world, we sit down and draw

up a structural description, or a set of

experiences, or a verbal description and say

“whatever I find that’s like this, I will call ‘a

dog’!”

The Paradox of Inquiry

The worry here is that on any of these models,

you can’t be radically wrong. If ‘gold’ is true of

what most closely resembles your idea of gold,

then most of your beliefs about gold must be

true. And the same goes for most of your beliefs

about anything. If representation is what fits

best with what you’ve drawn up in advance, in

advance of inquiry, you can be pretty sure you

already know what’s true and what isn’t.

The Paradox of Inquiry

In fact, this problem is as old as Plato, and it’s

called “the paradox of inquiry.” The paradox is:

suppose you want to know, say, the nature of

lightning. If you know what lightning is in

advance, then you don’t need to investigate,

because that’s what you wanted to know. But if

you don’t know, how do you know when you

discover it, that lightning is X? You find X, but

you don’t know that it’s lightning, because you

don’t know what lightning is!

Next Time

Next time we’ll look at the other aspect of the

paradox of inquiry. Let’s suppose we don’t

specify meanings in advance. How do we get

along in a world where we don’t (necessarily)

know what we mean?