Cardiac Electrophysiology and its Regulation Carmel M. McNicholas

advertisement

BIOLOGICAL MEMBRANES

AND PRINCIPLES OF

SOLUTE AND WATER

MOVEMENT

Carmel M. McNicholas, Ph.D.

Department of Physiology & Biophysics

Contact Information:

MCLM 868

934 1785

cbevense@uab.edu

Sept. ‘11

OUTLINE

•Biological Membranes and Principles of Solute

and Water Movement

•Diffusion and Osmosis

•Principles of Ion Movement

•Membrane Transport

•Nerve Action Potential

•HANDOUT AND PROBLEM SET

The Cell: The basic unit of life

(i) obtaining food and

oxygen, which are used

to generate energy

(ii) eliminating waste

substances

(iii) protein synthesis

(iv) responding to

environmental changes

(v) controlling exchange

of substances

(vi) trafficking

materials

(vii) reproduction.

The fluid compartments of a 70kg adult human

EXTRACELLULAR (~40%)

BLOOD

PLASMA

~3 L

[Na+] = 142 mM

[K+] = 4.4 mM

[Cl-] = 102 mM

[protein] = 1 mM

Osmolality =

290 mOsm

Capillary endothelium

INTRACELLULAR (~60%)

INTERSTITIAL FLUID

~13 L

[Na+] = 145 mM

[K+] = 4.5 mM

[Cl-] = 116 mM

[protein] = 0 mM

Osmolality = 290 mOsm

TRANSCELLULAR FLUID

~1 L

Composition:

variable

Epithelial cells

INTRACELLULAR

FLUID

~25 L

[Na+] = 15 mM

[K+] = 120 mM

[Cl-] = 20 mM

[protein] = 4 mM

Osmolality = 290

mOsm

Plasma membrane

TOTAL BODY WATER (~42 L)

Modified from: Boron & Boulpaep, Medical Physiology, Saunders, 2003.

Solute composition of key fluid compartments

•Osmolality

constant

•Cell proteins –

10-20% of the

cell mass

•Structural and

functional

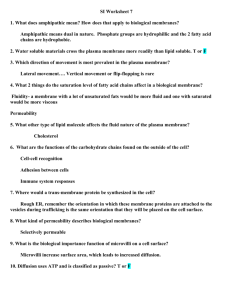

Membranes are selectively permeable

Gas molecules are

freely permeable

Small uncharged

molecules are freely

permeable

Large / charged

molecules need

‘assistance’ to

traverse the plasma

membrane

Structure of the Plasma Membrane

The Extracellular Matrix

Epithelial cell

Basement

membrane

Capillary

endothelium

Connective

tissue and

ECM

Fibroblast

The extracellular matrix

(ECM) of animal cells

functions in support,

adhesion, movement and

regulation

The Extracellular Matrix

The ECM is an organized meshwork of polysaccharides

and proteins secreted by fibroblasts. Commonly

referred to as connective tissue.

COMPOSITION:

Proteins: Collagen (major protein comprising the ECM),

fibronectin, laminin, elastin

Two functions: structural or adhesive

Polysaccharides: Glycosaminoglycans, which are mostly

found covalently bound to protein backbone

(proteoglycans).

Cells attach to the ECM by means of transmembrane

glycoproteins called integrins

• Extracellular portion of integrins binds to collagen,

laminin and fibronectin.

• Intracellular portion binds to actin filaments of the

cytoskeleton

The Cytoskeleton

Intracellular network of protein filaments

Role

Supports and stiffens

the cell

Provides anchorage for

proteins

Contributes to dynamic

whole cell activities (e.g.,

dividing and crawling of

cells and moving vesicles

and chromosomes)

Three Types Of

Cytoskeletal

Fibers

Microtubules (tubulin - green)

Microfilaments (actin-red)

Intermediate filaments

Structural Junctions

Tight

Junctions

Adhering

Junctions

Desmosome

Zonula Adherens

(belt)

Gap Junctions

ROLE: Passage of solutes (MW<1000) from cell to cell.

• Cell-cell communication

• Propagation of electrical signal

The Membrane Glycocalyx - cell coat

Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the

Cell, 4th Ed. Garland Science, 2002)

Carbohydrates are:

• Covalently attached to membrane proteins and lipids

• Sugar chains added in the ER and modified in the golgi

Oligo and polysaccharide chains absorb water and form a

slimy surface coating, which protects cell from mechanical and

chemical damage.

Membrane Carbohydrates and Cell-Cell Recognition

– crucial in the functioning of an organism. It is the

basis for:

> Sorting embryonic cells into tissues and organs.

> Rejecting foreign cells by the immune system.

Transport of large molecules

EXOCYTOSIS: Transport molecules migrate to the

plasma membrane, fuse with it, and release their

contents.

ENDOCYTOSIS: The incorporation of materials from

outside the cell by the formation of vesicles in the plasma

membrane. The vesicles surround the material so the cell

can engulf it.

Exocytosis

Endocytosis

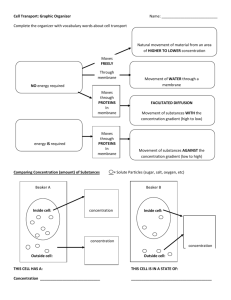

Principles of Solute

and Water Movement

Diffusion and Osmosis

Membranes are selectively permeable

Gas molecules are

freely permeable

Small uncharged

molecules are freely

permeable

Large / charged

molecules need

‘assistance’ to

traverse the plasma

membrane

Diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of a substance (liquid

or gas) from an area of higher conc. to one of lower

conc. due to random thermal motion.

Kinetic characteristic of diffusion

of an uncharged solute

Model: compartments separated by permeable glass

x

Cs1

compartment 1

Cs2

compartment 2

A = cross sectional area of the glass disc

Cs = concentration of uncharged solute

x = thickness

x

Cs1

compartment 1

Cs2

compartment 2

According to kinetics, the rate of movement can be

described as follows:

rate of diffusion from 1 2 = kCs1

-{rate of diffusion from 2 1 = kCs2}

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

net rate of diffusion across barrier

= k(Cs1-Cs2) = kCs

where k is a proportionality constant.

Diffusion is proportional to the surface area

of the barrier (A) and inversely proportional

to its thickness (x).

k can thus be expressed as ADs/x, where Ds

is the diffusion coefficient of the solute.

The concentration gradient across the

membrane is the driving force for net

diffusion.

FLUX (Js) describes how fast a solute moves, i.e. the

number of moles crossing a unit area of membrane per

unit time (moles/cm2.s)

Therefore, net diffusion rate = ADsCs/x.

Dividing both sides by A (to obtain flux), we obtain:

Fick’s first law of diffusion:

Flux = Js = DsCs/x

“The rate of flow of an uncharged solute due to

diffusion is directly proportional to the rate of change

of concentration with distance in direction of flow”

When the concentration gradient of a substance is zero

the system must be in equilibrium and the net flux must

also be zero.

Diffusion of an uncharged solute

Model: compartments separated by a lipid

bilayer

x

Cs1

compartment 1

Cs2

compartment 2

Biological membranes are composed of a lipid bilayer of

phospholipids interspersed with integral and peripheral

proteins (“Fluid Mosaic Model”).

Partitioning of an uncharged solute

across a lipid bilayer

The partition coefficient, Ks will increase or decrease the

driving force of the solute S across the membrane:

Js = KsDsCs/x

Cs1

Lipophilic

Ks > 1

Hydrophilic

Ks < 1

Ks lies between

0 and 1

Cs2

Because it is difficult to measure Ks, Ds and x, these

terms are often combined into a permeability coefficient,

Ps = KsDs/x.

It follows that:

Js = PsCs

Solute movement across a lipid

bilayer through entry into the lipid

phase occurs by simple diffusion.

This movement occurs downhill and

is passive.

Osmosis: The flow of volume

Osmosis refers to the net movement of water across

a semi-permeable membrane (or displacement of

volume) due to the solute concentration difference.

Osmosis. The flow of volume

The solute concentration difference causes water to

move from compartment 2 1. The pressure

required to prevent this movement is the osmotic

pressure.

Time

1

2

1

2

Osmosis. The flow of volume

AN IDEAL MEMBRANE

(Meniscus)

Piston

(The piston applies

pressure to stop

water flow)

H2O

Cs

1

Compartment 1

Cs

2

(Compartment 2

is open to the

atmosphere)

Compartment 2

Here the membrane is only permeable to water which will

flow down its concentration gradient from 2 1.

The volume flow can be prevented by applying pressure to

the piston. The pressure required to stop the flow of

water is the osmotic pressure of solution 1.

The osmotic pressure () required is

determined from the van’t Hoff equation:

= RTCS = (25.4)CS atm at 37°C.

Where, R = the gas constant (0.082 L.atm.K-1.mol-1),

T = absolute temperature (310 K @ 37 ºC) and CS (mol.L-1)

is the concentration difference of the uncharged solute

Osmosis. Importance of osmolarity

φic = osmotically effective concentration

φ is the osmotic coefficient

‘i’ is the number of ions formed by

dissociation of a single solute molecule

‘c’ is the molar concentration of solute

(moles of solute per liter of solution)

e.g. what is the osmolarity of a 154

mM NaCl solution, where φ = 0.93

→

154 x 2 x 0.93 = 286.4 mOsm/l

Osmosis. The flow of volume

A NONIDEAL MEMBRANE

Piston

S

Cs1

H2O

Cs2

The osmotic pressure depends on the ability of the

membrane to distinguish between solute and solvent.

If the membrane is entirely permeable to both, then

intercompartmental mixing occurs and = 0.

The ability of the membrane to “reflect” solute S is

defined by a reflection coefficient S that has values

from 0 (no reflection) to 1 (complete reflection).

Thus, the effective osmotic pressure for nonideal

membranes is:

eff = SRTCS

Osmotic and hydrostatic pressure

differences in volume flow

Volume flow across a membrane is described by:

JV = KfP

where Kf is the membrane’s hydraulic conductivity and P

is the sum of pressure differences.

These pressure differences can be hydrostatic (PH),

osmotic (eff) or a combination of both. There is

equivalence of osmotic and hydrostatic pressure as

driving forces for volume flow, hence Kf applies to both

forces.

Thus, JV = Kf(eff – PH) (Starling equation)

and (eff – PH) is the driving force for volume flow.

Starling Forces

Arteriole

Interstitial fluid

pressure under

normal conditions

~0 mmHg

Venule

Interstitial

space

= fluid

movement

Filtration dominates

Absorption dominates

Osmotic (oncotic) pressure

Importance of plasma proteins!

Tonicity

Principles of Ion Movement

Diffusion of Electrolytes

K+

Ac-

Cs1=100mM

Cs2=10mM

–

V

+

For charged species, both electrical and

chemical forces govern diffusion.

The Principle of Bulk Electroneutrality

All solutions must obey the principle of bulk

electroneutrality: the number of positive charges in a

solution must be the same as the number of negative

charges.

Diffusion of Electrolytes

Cs1=100mM

Cs2=10mM

K+

Ac– V +

Ac-

K+

Law of electroneutrality (for a bulk solution) must be

maintained. In the above model in which the membrane

becomes permeable to sodium (K+) and acetate (Ac–), both ions

will move from side 1 2.

The concentration gradient between compartment 1 and 2 is

the driving force.

K+ (with the smaller radius) will move slightly ahead of Ac–,

thereby creating a diffusing dipole. A series of dipoles will

generate a diffusion potential.

Eventually, equilibrium is reached and Cs1 = Cs2 = 55mM

Diffusion of Electrolytes

Cs1=100mM

K+

Cs2=10mM

Ac– V +

When the membrane is permeable to only one of the ions (e.g.,

K+) an equilibrium potential is reached. Here, the chemical and

electrical driving forces are equal and opposite.

Equilibrium potentials (in mV) are calculated using the Nernst

equation:

Eion

CS1

2.3RT

log 2

zF

CS

Eion

CS1

60

log 2

z

CS

R = gas constant; T = absolute temp.; F = Faraday’s constant; z = charge

on the ion (valence); 2.3RT/F = 60 mV at 37ºC

The Nernst Equation is satisfied for ions at

equilibrium and is used to compute the electrical

force that is equal and opposite to the

concentration force.

Eion

C

60

log

z

C

1

S

2

S

At the Nernst equilibrium potential for an ion,

there is no net movement because the electrical

and chemical driving forces are equal and

opposite.

• Even when there is a potential difference

across a membrane, charge balance of the bulk

solution is maintained.

• This is because potential differences are

created by the separation of a few charges

adjacent to the membrane.

Calculating a Nernst Equilibrium Potential

Cs1 = 100mM

Na+

Cs2 = 10mM

Ac– V +

Eion

C

60

log

z

C

1

S

2

S

For the model above, the Nernst potential for Na+,

ENa = 60 log(100/10) = +60 mV

Taking valence of the ion into account

in calculating a Nernst potential

Here, z = -1

ECl 60 log

ECl

Cl o

Cl i

[Cl-]i = 10 mM [Cl-]o = 100 mM

100

60 log

60 mV

10

EK 60 log

[ K ]o

[K ] i

[K+]i = 100 mM [K+]o = 10 mM

10

EK 60 log

60 mV

100

Equilibrium potentials of various ions for a mammalian cell

ION Extracellular

Conc. (mM)

Na+

145

Cl116

K+

4.5

Ca2+

1

Intracellular

Conc. (mM)

12

4.2

155

1x10-4

Equilibrium

Potential (mV)

+67

-89

-95

+123

Remember:

Log 10/100 = log 0.1 = –1

Log 100/10 = log 10 = +1

A 10-fold concentration gradient

of a monovalent ion is equivalent,

as a driving force, to an electrical

potential of 60 mV.

Membrane potential vs. equilibrium potential

When a cell is permeable to more than one ion then

all permeable ions contribute to the membrane

potential (Vm).

Membrane Transport

Mechanisms I

1. Most biologic membranes are virtually impermeable to:

Hydrophilic molecues having molecular radii > 4Å

e.g. glucose, amino acids)

Charged molecules

2. The intracellular concentration of many water soluble

solutes differ from the medium in which they are bathed.

Thus, mechanisms other than simple diffusion across

the lipid bilayer are required for the passage of

solutes across the membrane.

Transport across cell membranes

Transport through pores

A general characteristic of pores

is that they are always open.

Examples:

1) Porins are found in the outer

membrane of gram-negative

bacteria and mitochondria..

2) Monomers of Perforin are

released by cytotoxic T

lymphocytes to kill target cells

from: Boron, W.F. & Boulpaep, E.L., eds., Medical Physiology, 2003.

Transport Through Channels

General Characteristics of

ion channels:

1) Gating determines the

extent to which the

channel is open or

closed.

2) Sensors respond to

changes in Vm, second

messengers, or ligands.

3) Selectivity filter

determines which ions

can access the pore.

Source: Boron, W.F. & Boulpaep, E.L., eds., Medical Physiology, 2003.

4) The channel pore

determines selectivity.

Why do we need to know how ion channels

influence cells……..?

Macular degeneration

Na+ channel blocker

Solute movement through pores

and channels occurs via simple

diffusion, is passive and

downhill. Metabolic energy is not

required.

Transport through carriers

Carriers never display a continuous transmembrane path.

Transport is relatively slow (compared to pores and channels)

because solute movement across the membrane requires a

cycling of conformation changes of the carrier to allow the

binding and unbinding of a limited number of solutes.

Carrier mediated transport

Cotransporter Exchanger

Facilitated diffusion: the carrier transports solute from a

region of higher to lower concentration. No additional energy

sources are required.

Carrier-mediated transport:

Facilitated diffusion

Such proteins are important for:

1) the transport of cell nutrients and multivalent ions

2) ion and solute asymmetry across membranes

While diffusion processes display a linear relationship between

flux and solute concentration, carrier transport exhibit saturation

kinetics.

Hyperbolic plots of transport activity Jx vs. [X] are indicative

of Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics.

Carrier-mediated transporters display competitive inhibition

Fick’s 1st law

J max [ X ]

Jx

Km [ X ]

Carrier mediated transport:

Active Transport

• Movement of an uncharged solute from a region of lower

concentration to higher concentration (uphill)

• Movement of a charged solute against combined chemical

and electrical driving forces

• Requires metabolic energy

• Two classes: primary and secondary

Primary Active Transport – Na-K ATPase

• ATP-dependent

• Electrogenic

• Important for maintaining ionic gradients (conduction,

nutrient uptake)

• Important for maintaining osmotic balance

Secondary Active Transport-Symport

An example of a secondary active transporter is the

electroneutral Na/Cl cotransporter.

Na+

Cl-

Na+

The energy released from Na+ moving down its electrochemical gradient is

used to fuel the transport of Cl– against its electrochemical gradient. Note

that the Na+ pump plays an important role in maintaining a continual Na+

gradient.

Comparison of Pores, Channels, and Carriers

PORE

CHANNEL

CARRIER

Conduit through

membrane

Always open

Intermittently

open

Never open

Unitary event

None

(Continuously

open)

Open/close

Cycle of

conformational

changes

Particles

translocated

per ‘event’

---

60,000 *

1-5

Particles

translocated

per second

Up to 2

billion

1-100 million

200-50,000

* Assuming a 100 pS channel, a driving force of 100 mV and an open time of 1 ms

The “pump-leak” model

(generating the membrane potential)

Na+

K+

~

Na+

K+

Cl–

Pr–

The Na-pump that pumps 2 K+ into the cell in exchange for 3 Na+ out.

Under steady-state conditions, the diffusion of each ion in the opposite

direction through its channel-mediated “leak” must be equal to the amount

transported.

For most cells, however, PK > Pna. In the absence of a membrane potential, K+

would diffuse out of the cell faster than Na+ would diffuse in, thereby

violating the law of electroneutrality. Thus, a Vm is generated that reduces

the diffusion of K+ out of the cell and simultaneously increases the

diffusion of Na+ in.

Vm is generated by the ionic asymmetries across the membrane, which are

established by the Na-pump.

Gibbs-Donnan Membrane

Equilibrium

•Proteins are not only large, osmotically active

particles but they are also negatively charged

anions

•Proteins can influence the distribution of other

ions so that electrochemical equilibrium is

maintained

Gibbs-Donnan Equilibrium

Na+

Cl–

Na+

P–

1

Initially

Na+

Cl–

2

1

Na+

Cl–

P–

2

Equilibrium

In the simple model system above, Cl– will diffuse from 1

2, and Na+ will follow to maintain electroneutrality. In

compartment 2 then, Cl– will be present and [Na+]equil. >

[Na+]initial at Donnan equilibrium.

Because of the asymmetrical distribution of the

permeant ions, there must be a Vm that simultaneously

satisfies their equilibrium distributions.

Gibbs-Donnan equilibrium

(the tendency for cells to swell)

At equilibrium, the increase in osmotically active particles

leads to the flow of water into compartment 2.

Na+

Cl–

Equil.:

Na+

Cl–

H2O

1

P–

2

In animal cells, the presence of large impermeant

intracellular anions tends to lead to cell swelling due to

Donnan forces. However, the Na+ pump actively extrudes

osmotic solutes and counteracts the cell swelling.

The Na-pump (Na-K pump) is essential

for maintaining cell volume

K+

Na+

2K+

ClH 2O

~

K+

Na+

P-

[Na+]

+]

[K

3Na+ [Cl ]

Equal number of +ve and

–ve charges move:

Equilibrium

~

Cl-

P-

↑[Na+]

↓[K+]

↑[Cl-]

H2O

Inhibition of the Napump (ouabain) → cell

swelling

Membrane Transport

Mechanisms II

and the Nerve Action

Potential

Apical

Epithelia

Microvilli

Tight junction

Basal Lamina

Basolateral

• Lie on a sheet of connective tissue (basal lamina)

• Tight Junctional Complexes:

Structural

Allow paracellular transport

• Apical membrane; brush border (microvilli) –

increases surface area

• Apical (mucosal, brush border, lumenal) and

basolateral (serosal, peritubular) membranes have

different transport functions

• Capable of vectorial transport

Models of Ion Transport in Mammalian Cells

e.g. Cl- secretory cell

Transepithelial potential difference

NEGATIVE

POSITIVE

Na+

APICAL/

MUCOSAL

SIDE

K+

ClNa+

Na+ BASOLATERAL/

K+

SEROSAL/

ClBLOOD SIDE

K+

H2O

Paracellular

Transcellular

Absorptive Epithelia - e.g. Villus cell

of the small intestine

Na+-driven glucose

symport

Lateral domain

Carrier protein

mediating passive

transport of glucose

Basal domain

(Modified from: Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th Ed. Garland Science, 2002)

Common Gating Modes of Ion Channels

(Source: Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th Ed. Garland Science, 2002)

Diffusion of electrolytes through

membrane channels

The following are three important features of ion channels

that influence flux :

1) Open probability (Po). Opening and closing of channels are

random processes. The Po is the probability that the channel is

in an open state.

2) Conductance. 1/R to the movement of ions. Where V=IR

(Ohms law)

I

V

3) Selectivity. The channel pore allows only certain ions to

pass through.

Electrophysiological Technique: Patch Clamp

Terminology and Electrophysiological Conventions

Membrane

potential (Vm)

+100 mV

(Positive)

Depolarize

OUTWARD

CURRENT

I

V

0 mV

-100 mV

-100 mV

Hyperpolarize

+100 mV

Reversal

Potential

(I=0)

(Negative)

INWARD

CURRENT

How the behavior of an ion channels can be

modified to permit an increased ion flux:

Control/ Wild-type:

Closed state

Open state

An increase in conductance (more current flows/opening)

but the open probability stays the same:

Closed state

Open state

An increase in open probability (the channel spends more

time in the open state, or less time in the closed state)

but the conductance stays the same:

Closed state

Open state

Ionic currents through a single channel

sum to make macroscopic currents

TIMEdependent

closure

Na+ Channel

K+ Channel

VOLTAGE-GATED CHANNELS

VOLTAGEdependent

closure

The resting membrane potential (Vm) describes a

steady state condition with no flow of electrical

current across the membrane.

Vm depends at any time depends upon the

distribution of permeant ions and the permeability

of the membrane to these ions relative to the

Nernst equilibrium potential for each.

Overshoot

20

0

-20

-40

-60

-80

Resting

potential

Depolarizing phase

Membrane Potential (mV)

The Nerve Action Potential

Threshold

-5

0

Repolarizing

Phase

5

10 15 20

Time (ms)

After-hyperpolarization

Changes in the underlying

conductance of Na+ and K+ underlie

the nerve action potential

Chemical and electrical gradients prior

to initiation of an action potential

Na+

K+

+

•At rest, the cell membrane

potential (Vm-rest) is generated

by ion gradients established by

the Na- pump.

•The K+ conductance

(permeability) is high, Na+

conductance is extremely low,

hence Vm-rest is strongly negative.

A stimulus raises the intracellular potential to a threshold

level and voltage-gated Na+ channels open instantaneously

Stimulus

Na+

Na+

Na+

+

+

+ +

+ +

+

Na+

+

Na+

+

1. The membrane becomes permeable to Na+ and

there is a rapid Na+ influx due to due to both

electrical and chemical gradients. The cell

membrane potential becomes progressively, but

rapidly, more positive - i.e. it depolarizes

Membrane Potential (mV)

20

0

-20

-40

-60

-80

0

5

10

15

Time (ms)

The rapid upstroke, or

depolarizing phase, is due to

an increase in Na+ conductance

of the cell membrane due to

activation of voltage-gated

Na+ channels. An all-or-none

response. The cell potential

moves toward ENa due to

20 chemical and electrical driving

forces. Vm does not reach ENa.

Na+

K+ Cl-100

-50

0

+50

+100

+150

Eion

2. Na+ channels Na+

begin to close:

+

+

+

+

+

+

Na+

+

+

+

+

+

+

K++

+

+

+

3. Outward K+ gradient

K+

4. Outward

flux

as voltagedependent K+

K+

channels open

hyperpolarization

K+

- -

- -

-

K+

K+

5. Cell repolarizes

Membrane Potential (mV)

20

0

-20

-40

-60

-80

0

5

10 15

Time (ms)

20

As the cell depolarizes, the

Na+ channels inactivate and

the permeability to Na+ is

reduced. Voltage-gated K+

channels open and the cell

membrane potential becomes

permeable to K+ thereby

driving Vm toward EK. The

continued opening of K+

channel causes a brief afterhyperpolarization before the

cell returns to its resting

membrane potential.

K+ Cl-100

-50

Na+

0

+50

+100

Ca2+

+150

Eion

Gates Regulating Ion Flow Through

Voltage-gated Na+ Channels

DEPOLARIZING Vm

REST

ACTIVATED

(UPSTROKE)

INACTIVATED

out

in

Na+

REPOLARIZATION

→HYPERPOLARIZATION

Activation gate

Inactivation gate

REFRACTORY PERIODS

During RP the cell is incapable of eliciting a normal

action potential

• Absolute RP: no matter how great the stimulus an

AP cannot be elicited. Na+ channel inactivation gate is

closed.

• Relative RP: Begins at the end of the absolute PR

and overlaps with the after-hyperpolarization. An

action potential can be elicited but a larger than

normal stimulus is required to bring the cell to

threshold.

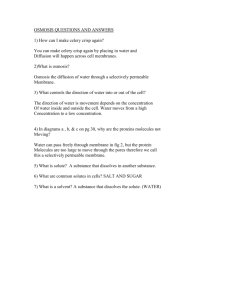

REVIEW AND PROBLEM SET

Review Question 1

Solute

A+

B+

C++

DEFG (uncharged)

H (uncharged)

Intracellular

conc. (mM)

7

110

1

5

10

2

4

3

Extracellular

conc. (mM)

104

8

0.01

10

100

2

4

1

A. If the membrane potential of a hypothetical cell is –60 mV (cell

interior negative):

a) Given the extracellular concentration listed on the table

above, what would the predicted intracellular concentration

of each of the solutes A-H have to be for passive diffusion

across the membrane.

b) Given the intracellular concentrations calculated in part a),

what can we conclude about the transport mode of each of

the solutes that are not passively distributed.

B. Calculate the Nernst equilibrium potential for each solute.

Review Question 2

Consider a closed system bound by rigid walls and a rigid membrane

separated the two compartments. Assume the membrane is freely

permeable to water and impermeable to sucrose.

Piston

A

B

A) If both compartments contain pure water and a pressure is applied to

the piston establishing a hydrostatic pressure difference across the

membrane, which direction will water flow in? What will the initial rate of

water flow depend on?

B) If no force is applied to the piston and 100 mM sucrose is placed in

compartment A, which direction will the meniscus in compartment B move?

What concentration of NaCl (also impermeant) would have to be added to

compartment B to prevent volume displacement? What hydrostatic

pressure must be applied to the solution in compartment A to prevent this

volume flow?

Review Question 3

Consider two compartments of equal volume separated by a membrane that

is impermeant to anions and water

A

100 mM

NaCl

10 mM KCl

100 mM KCl

10 mM NaCl

B

A) If in addition the membrane is not permeant to Na+, what is the

orientation and the magnitude of the potential difference across the

membrane at 37C? What is the composition of compartment B when the

system reaches equilibrium?

B) If the properties of the membrane change and now the membrane is only

permeant to Na+, what is the orientation and magnitude of the potential

difference?

C) If both Na+ and K+ are permeable, but PNa>PK what will be the orientation

of the potential difference initially? What will be the orientation of the

potential difference and the composition of compartments A and B when

electrochemical equilibrium is reached?