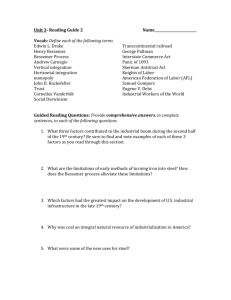

summaries provided - Amanda Church

advertisement

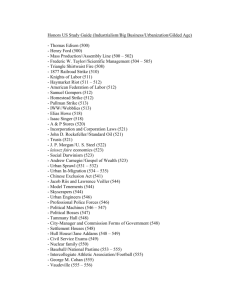

Railroad Strike of 1877 (Great Railroad Strike of 1877) The nation’s first strike took place in 1877 when workers on the Baltimore and Ohio and other Eastern Railroads walked off the job to protest a wage cut. When railroads hired other workers to replace them, the angry strikers tried to keep the trains from running. Riots broke out, and pitched battles were fought between strikers and militia. Much property was destroyed in several railroad centers, especially Pittsburgh. Order was finally restored when President Hayes sent in federal troops. Unable to prevent trains from running, and afraid of losing their jobs, the strikers reluctantly accepted the wage reduction. Haymarket Riot Encouraged by the impact of 1877 strike, labor leaders continued to press for changed. On the evening of May4, 1886, 3,000 people gathered at Chicago’s Haymarket Square to protest the slaying of several strikers by police at the McCormick Harvester plant a short time earlier. As the meeting was nearing its end, police arrived on the scene. A bomb was thrown, killing seven Pinktertons (hired police) and wounding dozens of bystanders. Additional people were hurt in the panic that ensued. Although no one knew who actually threw the bomb, eight radical agitators were arrested for the crime, tried, and found guilty. Four were executed, one committed suicide, and the others received life sentences. Despite the fact that the Knights of Labor had not sponsored the Haymarket Riot and had condemned the bombing, the public and the press blamed the union for the incident. Therefore, membership declined in the Knights of Labor and it eventually disappeared. After the Haymarket Riots, employers were much more reluctant to hire anyone associated with labor unions. Homestead Strike Refusing to take a cute in wages, workers of the Carnegie Steel Company in Homestead Pennsylvania struck in 1892. The company attempted to bring 300 unarmed guards from private detective agency to protect its property and break the strike. In a battle between the strikers and the guards, 10 detectives were killed and the rest were driven off. Under the protection of state militia, strikebreakers were hired to resume steel production. After 5 months and facing starvation due to no money, the strike collapsed and the striking workers accepted the company’s terms; however, Carnegie denied many the opportunity to come back to work and had many strikers blacklisted. It would take another 45 years for steel workers to gain enough support to strike again Pullman Strike During the Panic of 1893 and the economic depression that followed, the Pullman Company laid off more than 3,000 employees and cute wages of the rest by 25 to 50 percent, without cutting the cost of its employee housing. After paying their rent, many workers took home less that $6 a week. Threatened with a wage cut, workers at the Pullman Company’s sleeping-car manufacturing plant near Chicago went out on strike in 1894. Railroad employees across the country supported the strikers by refusing to handle any train hauling Pullman cars. This support brought nearly all trains to a halt. Violence flared up when the railroads tried to keep trains running. President Grover Cleveland dispatched federal troops to restore order and keep mail serve from being disrupted. The railroads meanwhile obtained a court order, or injunction, that forbade the strikers from interfering with mail transportation and interstate commerce. When the strike leaders refused to call off the walkout, they were arrested for violating the injunction. With the strike leaders in jail and train service restored under the protection of federal troops, the strike was broken. Anthracite Coal Strike The United Workers struck in 1902 after the mine owners in Pennsylvania refused to recognize the union or to discuss a wage increase. With winter approaching, President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to seize and operate the mines with federal troops to avoid a fuel shortage. Thereupon, the owners agreed to allow an impartial commission to arbitrate the dispute, and the mines called off their strike. The commission awarded the miners an increase in wage but rejected their demand for union recognition. Roosevelt’s intervention and forced compromise is an example of what he referred to as a “square deal.” Roosevelt’s actions had demonstrated a new principle. From then on, when a strike threatened the public welfare, the federal government was expected to fix it.