Jenni Ward - University of Auckland

advertisement

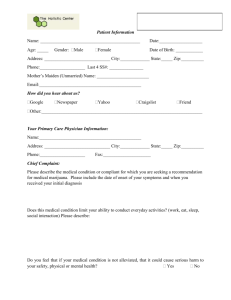

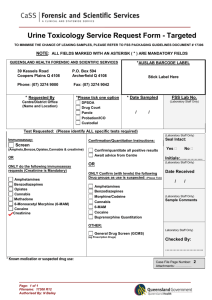

Rethinking Drug Policy: Punishment and Sentencing within the Courts Dr. Jenni Ward Middlesex University, UK j.r.ward@mdx.ac.uk Introduction • Paper based on observations in the criminal courts examining the penalties dispensed for small quantity drug possession charges • Situate my research within the within the broader drug policy debates occurring at the international and European level that are calling reformdepenalising policies • Apply a conceptual framework that problematises the notion of ‘harm’ – whose harm is it? Current drugs policy debates • A lively drugs policy debate is currently going on at international and European levels, and radical change is occurring in nation states • The notion that the prohibitionist, law enforcement stance to drugs has not worked in efforts to deter people from using, and trading in drugs (Bewley-Taylor et al, 2009) – the ‘War on Drugs’ has failed! • A desire for ‘pragmatic’ responses to drugs -harm reduction, educationalist approaches, rather than penalising ones. • Contributing voices come from international and national pressure groups eg. ‘International Drugs Policy Consortium’, ‘Global Commission on Drug Policy’, Global Initiative for Drug Policy Reform, politicians and political parties • International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) launch a counteroffensive • Two general points to the debates: • 1. Drug-addicted offenders should be diverted into health and treatment services • 2. The offence of drug possession for ‘personal use’ should be depenalised, whatever the drug category ie. heroin, crack cocaine, cannabis etc. A starting point to my research • A European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drugs Addiction (2009) report suggested the idea that we can divide countries into those with ‘repressive’ or ‘liberal’ drugs policies was problematic- ‘value laden’ and ‘meaningless’ concepts (EMCDDA, 2009). • There is little detailed research on the level of disposals given out for drug possession offences, and to who? • Official statistics illustrate the proportion of cases dealt with by fines or community penalties etc., but nuanced detail is missing My research • Observations in three London magistrates’ courts (btw. Sept. 2010 and April 2012), over 12 morning court sittings • Recorded the type and quantity of drug the person was in possession of, how and where they were arrested, whether they pleaded guilty or not, background circumstances of the defendant, and the disposals handed out Total drug possession cases n=27 Gender Male x26 Female x l Age (yrs) 18 20 =2 20-29 =13 30-39 =8 40-49 =3 50 and over = 1 Ethnicity White Black Asian =6 =15 =6 Drug possession offences Cannabis x17 Cocaine powder x8 Heroin x1 Crack cocaine x1 Socio-economic status Paid employment x 1 State benefits x 25 Disability Living Allowance x 1 Pleas entered Guilty x 20 Not guilty x 6 Discharged x 1 Socio-demographics Drug possession amount Penalty dispensed Penalties 1. 2. 3. M, 18 yrs, asian M, late 30s, black M, 28yrs, black 1 cannabis spliff 1 cannabis cig Possession of a cannabis joint 4. M, mid 20s, asian Offering to sell cannabis to a PC Sentencing delayed to follow a probation report 5. M, 24 yrs, Asian one cannabis cigarette 6. M, 31 yrs, white A small quantity of cannabis Fine: total £170 plus 20 hours unpaid work to be added to previous 180 hours Fine: total £200 7. M, 22 yrs, white small bag of herbal cannabis Fine: total £165 8. M, 40 yrs, white Small bag of herbal cannabis Fine: total £150 9. F, 24 yrs, white 2 bags herbal cannabis 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. M, 39 yrs, black M, 44, yrs, black M, 21 yrs, Asian M, 18 yrs, black M, 24 yrs, black 2 wraps of cannabis 1 wrap of herbal cannabis 3 wraps of cannabis 1 sealed bag of cannabis 1 small bag of cannabis Conditional discharge but £30 toward prosecution costs Fine: total £130 Fine: total £120 Fine: total £115 Fine: total £50 Breach of penalty – sent to Crown Court for review 15. M, 32 yrs, black 16. M, 22 yrs, Asian 17. M, early 20s, black Conditional discharge for 12 months Fine: total £115 Fine: total £166 Possession of small quantity of Fine: total £115 cannabis A wrap of cannabis Fine: total £100 Possession of 3 wraps of Lowest end of community order Electronic tag for cocaine 4 weeks and curfew order 8pm to 8am 18. M, 29 yrs, black Small package of cocaine £40 Sent for probation appointment 19. M, 39 yrs, white 20. M, 32 yrs, white £10 wrap of crack 1ml of diamorphine Fine: total £205 Fine: total £147 Observation findings • A relatively high number of small quantity (ie. “a £10 bag of cannabis”) drug possession cases appeared in court • Significant financial penalties were received (range £50-205) • Variable application of the drug laws, ‘police discretion’ - who gets arrested, and proceeded for prosecution? Observation findings (ctnd.) • Drug arrests were made through random ‘stop and search’ under the pretext of ‘suspicion’. • Questions emerged on sentence utility – what purpose was the punishment to serve? i.e. deterrence, retribution etc. • Problems with the drug laws - the dual purpose of the A to C classification system – expresses the severity of drug harm to personal health as well as dictating the severity of penalties for drug offences Drugs harm • The ‘harm principle’ – conduct should be criminalised only if it is harmful, problems with criminal wrongdoing that occurs without causing direct harm • Drugs criminalisation is based on notion of harm • Ruggiero (2000) in his writing on drug prohibition and legalisation draws on work of the political philosopher John Stuart Mill (1859) on harm and individual freedom Harm and individual freedom of choice • Mill’s seminal work ‘Liberty’ (1859) queried what personal actions the state should legitimately intervene in in its endeavour to preside over a productive, free, and moral society • Mill judged apart from when individual actions caused wider societal harm, or impacted on personal responsibility people should be ‘free’ • Ruggiero argues prohibitionists take advantage from the position that Mill puts forward that government legal intervention is justified because drugs cause wider societal harm –public health, safety, violence problems etc. • The principle lends itself to a range of interpretations • Conversely legalisers can also use the argument of harm to argue for drug law reform Whose harm? • Increasingly the discourse of alternative drugs policies considers the drug-related harm to be inclusive of the impact law enforcement has on peoples’ finances, liberty and future employment, travel options – disproportionate impact • Human rights violations of some drugs penalties namely the imprisonment of drugs addicts and the denial of appropriate treatment and care. • Can we convincingly argue the possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use causes little societal harm and should therefore be dealt with in ways other than through criminal prosecution? References • Bewley-Taylor, D. Hallam, C. and Allen, R. (2009) The Incarceration of Drugs Offenders: An Overview. The Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Programme. www.idpc.net • EMCDDA (2009) Drug Offences: Sentencing and Other Outcomes. European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction: Lisbon. Available from www.emcdda.europa.eu • Greenwald, G. (2009) Drug Decriminalisation in Portugal: Lessons for Creating Fair and Successful Drug Policies. Cato Institute: Washington available: www.cato.org/pubs/wtpapers/greenwald_whitepaper.pdf • Law Commission (2011) Controlling and Regulating Drugs: A Review of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. www.lawcom.govt.nz References • Nutt, D., King, L. and Phillips, L. (2010) Drug Harms in the UK: A Multicriterian Decision Analysis. The Lancet, 3761558-65. • Ruggiero, V. (2000) Crime and Markets. Oxford University Press: Oxford. • Stewart, H. (2009) The Limits of the Harm Principle, Criminal Law and Philosophy’ • Ward, J. (2013) The Punishment of Drug Possession Cases in the Magistrates’ Courts: Time for a Rethink, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research,19, 4, 289-307.