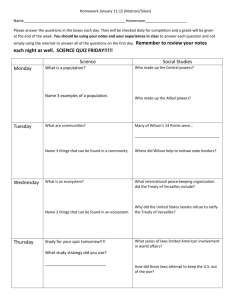

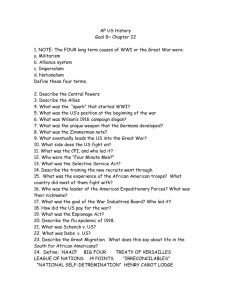

World War I Lecture Notes PowerPoint

WORLD WAR I

1914-1918

Key Concepts

• German violations of American neutrality, strong economic, and political ties to Britain, and effective British propaganda helped shape American public opinion about the combatants.

• Despite a strong desire on the part of the American public to remain neutral, the United States entered the conflict in 1917.

• WWI affected American civil liberties as the government suppressed dissent.

• The punitive nature of the Treaty of Versailles laid the foundation for resentment in Germany.

• Woodrow Wilson’s idealism, as articulated in the Fourteen

Points, including the establishment of a League of Nations, was challenged at home.

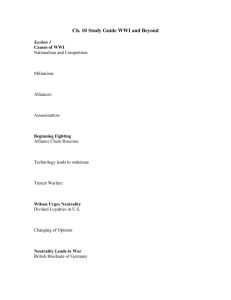

Causes of WWI

• While the United States entered the war fully three years after it began, it is important for the student to identify the major factors that brought the European powers into conflict. All historical events involve a multiplicity of shortand long- term causes, but four primary factors led to the onset of WWI in 1914:

• Militarism

• Alliances

• Imperialism

• Nationalism

Militarism and Alliances

• Increased militarism:

• The major European powers had been stockpiling military arms and expanding the size of their armies and navies. For example, the naval arms race between Britain and Germany exacerbated relations between the two. Further, in France a strong sense of revenge against the Germans for the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War over thirty years earlier was still strong. In that conflict, the French suffered a humiliating defeat and the loss of two key provinces, Alsace and

Lorraine.

• The formation of sometimes-secret military alliances:

• Distrust among the rival imperialist European nations led to the creation of antagonistic alliances. The two most important were the

Triple Alliance (later known as the Central Powers and comprising of

Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) and the Triple

Entente (later known as the Allies and comprising Great Britain,

France, and Russia). The United States, Italy, and Japan would later side with the Allies.

Imperialism and Nationalism

•

•

The growth of imperialism:

• In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, European powers raced to acquire colonies-in some cases simply to prevent their rivals from obtaining land that often had dubious benefits, as expressed in the term, the “scramble for Africa.” This in turn led to increased tensions and threatened military conflicts among the European imperial powers. For example, the French and Germans nearly came to blows over control of Morocco, and German-British competition for markets in Africa and the Middle East increased tensions between the two. To make matters worse, there was no permanent international organization to settle disputes between nations.

The rise of nationalism:

• Those ethnic groups that had earlier been absorbed into large

European empires sought self-determination and desired freely elected governments that would best represent their interests. The

Austro-Hungarian Empire is a prime example of a patchwork nation comprising a variety of ethnic and religious groups held together by an autocratic monarchy.

Causes of WWI

• The stage was set for war. The spark that started it was the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Francis Ferdinand, by a Serb nationalist in June

1914. Tensions rose to a fever pitch when the Austrian government blamed Serbian authorities for the assassination. Reeling from the murder, Austrians nonetheless saw it as an opportunity to crush Serbian nationalism once and for all and quell Serb dissent within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A harsh ultimatum was given to the Serbs, who failed to meet the Austrian demands. On July 28 Austria-Hungary declared war on

Serbia. Two days later Serbia’s ally, Russia, entered the war, followed in short order by the other European powers-and ultimately non-European nations as well.

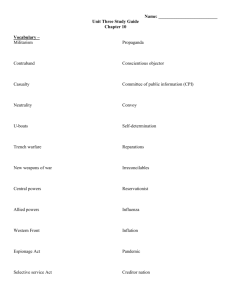

American Neutrality

• When war broke out, President Wilson was determined to keep the

US out of the conflict. He was deeply concerned that the war would seriously interrupt international trade and, worse, that the US might be drawn into the maelstrom. Somewhat unrealistically Wilson believed that a neutral US could somehow mediate an end to the dispute. But as we will see, if Wilson’s hope of mediating an end to the war in 1914 or 1915 was nearly impossible, working out the peace terms proved equally challenging.

• For both the Allies and Central Powers the demands of war required that they interrupt each other’s expansive trade relationships, which included, of course, the US. To this end, the British blockaded

Germany in hopes of cutting off supplies to the Central Powers. In violation of international maritime law, the British were in fact in violation of international law, the British government claimed it was seizing contraband obviously intended for Germany and that it was not interfering with trade destined for neutral ports.

American Neutrality

• To the delight of the British, German violations of neutrality soon overshadowed their own transgressions. Early in 1915 the Germans declared that British waters would be deemed a war zone and that all shipping in that area could be attacked by

German Uboats (submarines). From Germany’s perspective, the loss of civilian lives could be avoided if neutrals stayed outside this zone and refrained from sailing on Allied ships.

The very nature of submarine warfare-namely, stealth-often required U-boat captains to attack ships without first stopping and searching them for contraband. Not surprisingly, this led to the sinking of neutral ships and the loss of civilian lives. For the US, the policies of both warring sides seriously interfered with freedom of the seas and placed American citizens in harm’s way. The same year the British instituted their blockade, the inevitable happened. A British passenger liner, the Lusitania, was sunk by a German U-boat, resulting in the loss of over a thousand passengers, including 128 Americans.

American Neutrality

• In 1916 Wilson threatened to cut off diplomatic relations with

Germany if unrestricted submarine warfare continued to cost the lives of Americans and jeopardize American shipping.

Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan resigned in protest, believing that Wilson’s rhetoric would bring the US into the war.

But when two Americans were injured after a French ship, the

Sussex, was torpedoed, Wilson threatened to break off diplomatic relations with Germany. The Germans were at the time fighting the war on two fronts, against the British and

French in the west and the Russians in the east. Keeping the

US out of the war was a German priority, and so the Germans promised not to sink passenger ships carrying noncombatants without warning and without care for the lives of the passengers (the “Sussex pledge”). For the better part of 1916, the Germans held true to their word.

US Relations with Britain and France,

Public Opinion, and War Propaganda

• Prior to the war the US had experienced a recession, but

French and British military contracts helped stimulate a recovery. By 1915 the economy had rebounded in terms of production and business profits. Of course, the US manufacturers wanted to ship supplies to the Germans as well as to the Allies, but the British blockade of Germany prevented this. Whereas between 1914 and 1917 US trade with the Allies quadrupled, trade with Germany all but dried up, US economic interests and the Allied war effort became even closer when US financiers such as JP Morgan were given permission by the US government to extend $3 billion in credit to Britain and France.

To be sure, had the Allies lost the war, that money would be lot to US bankers, a factor that probably played a role in the eventual decision by the US government to intervene in the war.

US Relations with Britain and France,

•

Public Opinion, and War Propaganda

Most Americans supported the Allied war effort for noneconomic reasons, a perspective that was shaped in part by the effectiveness of British propaganda, which depicted Germans as modern-day Huns brutalizing

Belgians and anyone else who stood in their way. Yet support for one side or the other depended in large part on one’s ethnicity. For example,

German Americans supported the Central Powers, whereas Italian

Americans supported the Allies after Italy entered the in 1915. Many Irish

Americans supported the Central Powers because of their hatred for the

British government. Some Americans identified with the French because of their perceptions of a shared revolutionary past and French help during the American Revolution. Still, even by early 1917, most

Americans, especially in the Midwest and West, were opposed to US involvement in what they perceived as an entirely European affair.

National leaders such as former Secretary of State Bryan, social activist

Jane Addams, and Jeanette Rankin, the first women elected to

Congress, gave voice to sentiment for American neutrality, though once the US entered the war most opposition dwindled. However, American socialists, unlike European socialists, maintained their opposition to the war from beginning to end and were often imprisoned for expressing their views or refusing to serve in the military.

US Intervention

• In early 1917 the Germans decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. While probably a necessary military measure, it was one of the primary reasons the US entered the war in November of that year.

The immediate response of the US was “armed neutrality”-that is, US merchant ships would be armed in order to protect themselves from the stealthy U-boats. The Germans fully realized that their resumption of unrestricted U-boat warfare would probably draw the

US into the war, but they gambled that American intervention would come too late to effect a change in the course of the war. In February

1917 the British intercepted a diplomatic telegram written by

Germany’s foreign minister, Alfred Zimmerman, to Mexico. When the telegram, referred to as the Zimmerman note, was published,

Americans were shocked by the offer made by Zimmerman to Mexico: in return for Mexico’s military assistance in the event the US entered the war, Mexico would receive most of the land it had lost in the

Mexican-American War if the Central Powers were victorious.

US Intervention

• In March 1917 the Romanov Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was overthrown by revolutionary democratic forces. The provisional government kept Russia in the was until Lenin’s Bolsheviks took power and signed a peace treaty with Germany, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in 1917. But the overthrow of the tsar convinced Wilson that repressive regimes like Tsar Nicholas’s and Kaiser Wilhelm II’s represented a threat to democracy and economic liberalism. Wilson inched ever closer to the idea that the war, and specifically US involvement in it, was a struggle

“to make the world safe for democracy.” On April 2, 1917,

President Wilson called for a special session of Congress at which he asked for a declaration of war in order to stop

Germany’s “warfare against mankind.” On April 4 Congress concurred; the US was at war with Germany and its allies.

WWI - Suppression of Civil Liberties and

•

Dissent

Given the nearly unanimous support in Congress for the war, one would think that the entire nation embraced US intervention. But the actions of the government in 1917 and

1918 indicate that it was deeply concerned with domestic dissent. For example, the following legislation passed to address this “problem”:

• Espionage Act of 1917 This called for fines and imprisonment for anyone “aiding the enemy” by obstructing the war effort. The postmaster-general was authorized to ban the dissemination of

“treasonable literature”. Socialist leader and 1912 presidential candidate Eugene Dens was convicted and imprisoned for violating the act. In 1919 the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the

Espionage Act in its decision Schenck v. United States , a case involving an individual who used the mail to attempt to dissuade draftees from reporting for induction in the military. Justic Oliver

Wendell Holmes argued that such actions presented a “clear and present danger” to national interests and therefore First Amendment free-speech rights could be limited by the government.

WWI - Suppression of Civil Liberties and

Dissent

• Sedition Act of 1918 This law made it a criminal act punishable by fine fine or imprisonment to attempt to persuade or discourage the sale of war bonds or to in any way disparage the military, the

Constitution, or the government.

• To complement its attack on dissenters, the government created the Committee of Public Information (run by George Creel, who, interestingly enough, was a progressive). In the process of equating the government’s case for war and patriotism, the committee’s work set of a groundswell of distrust. Immigrants and those with foreignsounding names were considered “un-

American”.

The Economics of War

• The federal government’s intervention in the economy increased profoundly during the war was more and more agencies and resources centralized under the government’s control. This would serve as a foundation and precedent for later governmental interventions (the New Deal for instance) and as a way to resolve economic problems and organize the expansive nature of American capitalism. The following are representative of this centralization:

• War Industries Board (1917) Led by Bernard Naruch, the board was created to coordinate all aspects of industrial production and distribution.

• Lever Act (1917) Led by Herbert Hoover as food administrator, this act aimed to mobilize agriculture and establish prices to encourage production.

• War Labor Board (1918) This board arbitrated management-labor disputes, prevented labor strikes, and regulated wages and work hours.

The Economics of War

• To be sure, US economics and military intervention in the war helped break the stalemate that he shaped warfare on the

Western Front, where the Allies and Central Powers battered each other month after month, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage. For Germany, the war was sapping its resources and public support for continuing to fight. After the

Allies launched a major offensive in the fall of 1918, it became abundantly clear to the Germans that their nation would ultimately be invaded. The kaiser abdicated and was replaced by a representative government, which agreed to an armistice in November 1918. The “war to end all wars” has ended, but not before claiming millions of lives, of which over fifty thousand were Americans. The war had cost over $300 billion.

Four great empires-Russian, German, Ottoman, and Austro-

Hungarian-collapsed in the process.

Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

• The “Big Four” (Wilson, France’s Clemenceau, Britain’s Lloyd

George, and Italy’s Orlando), representing the victorious Allied

Powers, met in Paris and Versailles, France, in 1919 to work out the details of the peace treaty that would be imposed on the defeated

Central Powers. Having suffered enormous losses, the European

Allies sought a punitive peace treaty. Despite Wilson’s misgivings about the harsh punishment meted out to Germany in the Treaty of

Versailles, the following provisions were adopted:

• The provinces of Alsace and Lorraine (lost by the French in the Franco-

Prussian War) were returned to France.

• Germany was prevented from placing troops on the western side of the Rhine

River.

•

•

•

The German military was dramatically reduced in size and strength.

Germany was to ship coal from occupied Saar region to France for a period of fifteen years.

Germany lost all of its colonies.

•

•

New nations were created: Estonia, Latvia, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and

Poland.

Austria-Hungary lost three-fifths of its land and three-fifths of its population.

•

•

The Central Powers were to pay crushing reparations.

Germany was branded with “war guilt” as the primary perpetrator of the war.

Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

• For his part, Wilson was greatly disturbed by the harshness of the treaty, even threatening at one point to negotiate a separate treaty with Germany. Instead, he outlined his vision for the postwar world in a list of political and economic objectives referred to as the Fourteen Points. They included:

• The elimination of secret treaties, the stimulus for which was the

Bolshevik revelation that Britain and France engaged in this diplomatic practice prior to the war.

• Open access to the seas in times of war and peace, which was important for economic expansion and trade

• Reduction of military stockpiles

• Adjustment of colonial claims

•

•

Self-determination for Europeans, but not for those under colonial control

The creation of an international assembly that would “afford mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity”

Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

•

•

Wilson believed that the fourteenth point-his call for the creation of what ultimately became the League of Nations- could be the basis for resolving the problems associated with the first thirteen points. Open to all nations, this international body would be the forum for resolving international disputes and making military confrontation obsolete.

Wilson worked tirelessly to convince the American people and Congress to support the Versailles Treaty. Unfortunately, the conference were all

Democrats, which angered and antagonized the most influential member of the Senate, Henry Cabot Lodge. Wilson’s second political blunder was to travel to France for the peace talks rather than mobilize support for the treaty at home. Wilson’s emphasis on the treaty made it the most important issue of the 1918 Senate elections. He took his appeal for its ratification directly to the American people in an exhausting national speaking tour, which ultimately broke his health. A stroke, in September

1919, paralyzed not only his body, but his personal crusade to see the treaty ratified. Senator Lodge, for his part, offered certain important reservations to the treaty that would have diminished the role and commitment of the US to the League of Nations. With Senator Lodge and the “irreconcilables” (those staunchly opposed to the treaty) in the vanguard, the opponents of ratification won the day. Although the issue of admission to the League was taken up after Wilson left the White

House, the US never became a member of that body.

The Interwar Years

• Shocked by the enormous loss of life in the war, world leaders grasped at ways to prevent such a thing from happening again. The League of Nations was seen as one method, but without US and Soviet involvement, its potential for solving international disputes was limited.

Nevertheless, various international agreements were made in the interwar years to limit the size of militaries and resolve potential political disputes. Some were practical, others, rested on naïve optimism.

• The Five-Power Naval Treaty At the Washington “Disarmament”

Conference (1921-1922_ convened by President Harding, the US,

Britain, Japan, France, and Italy agreed to limit their capital ships to the following ratio respectively: 5:5:3:1.7:1.7 The participants also agreed to ban the use of certain insidious weaponry such as posion gas and restricted submarine warfare.

The Interwar Years

• The Four-Power Treaty At the same conference, the US, Britain,

Japan, and France agreed to respect one another’s Pacific territorial possessions by, in part, not creating forward military bases in the Pacific.

• The Nine-Power Treaty Yet another product of the same conference, this treaty reaffirmed the Open Door policy in China.

• Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) This international agreement outlawed war. However, it made no provision for enforcement, nor did it provide for defensive wars.

Economic Imperatives: Intervention, WWI Debts, and Reparations

• The interwar years were dominated by Republican presidents whose domestic and foreign policies were designed to advance

American business interests. To this end the Coolidge administration saw to it that a new constitution passed by

Mexico in 1917, which called for nationalizing Mexico’s important industries, would not jeopardize American investments in those businesses. Throughout the 1920s US troops were sent to South America and the Caribbean to reinforce US backed regimes and to protect US financial interests. Of equal concern to US policymakers and financial institutions were the billions of dollars in loans extended to the

Allies during the war. President Coolidge wanted the debts repaid, but the Europeans balked, claiming that they were unable to collect the billion in war reparations owed to them by a bankrupt Germany and adding that US losses paled in comparison to their losses. Equally troubling was the US passage of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff. The Tariff made it exceedingly difficult for Europeans to sell their products in the

US and make the money that could be used to pay back the war loans.

Economic Imperatives: Intervention, WWI Debts, and Reparations

• In response to this problem, the US offered the following solutions:

•

• The Dawes Plan This plan significantly reduced Germany’s reparations and provided loans to Germany in a roundabout way: the US loaned money to Germany, Germany used this to pay its reparations to the Allies, who in turn used these funds to pay off the interest on its war debts to the US.

The Young Plan This plan further reduced Germany’s payments and established the Bank of International Settlements to assist in the process of reparations payments.

• Nevertheless, the collapse of national economies brought on by the Great Depression caused most nations to default on their debt payments to the US.

Economic Imperatives: Intervention, WWI Debts, and Reparations

• Throughout the 1920s and will into the 1930s, the US continued to influence the affairs of its own hemisphere as well. Time after time it intervened in Central and Latin America in order to protect US economic and political interests while simultaneously it attempted to draw those nations closer to the US, especially in light of the rise of antagonistic governments in Japan, Germany, and Italy. At the Pan-

American Conferences of 1923 and 1928, the US agreed to treat all nations on an “equal footing.” The Clark Memorandum of 1928 took this rapprochement one step further by repudiating the Roosevelt

Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. Later, in the 1930s, President FDR would replace Dollar Diplomacy with the Good Neighbor policy, which stated that no nation would interfere in another’s international affairs.

For the time being, this new, less hegemonic policy satisfied most

South Americans. Even in the far reaches of the American empire, the Philippines, and the US, partially recognizing the costs of maintaining an international empire, promised Filipino independence by 1946(Tydings-McDuffie Act). Post-World War II international affairs, however, would convince US administrations to pull back from these prewar agreements and statements.

Economic Imperatives: Intervention, WWI Debts, and Reparations

• In the two decades following the war, as the horrors of

WWI battlefields faded from public consciousness, the US experienced an economic boom, highlighted by the

“roaring Twenties.” But the harshness of the Versailles

Treaty, the onset of the Great Depression, and the rise of militarism and imperialism in Europe and Asia would guarantee that the peace would not be maintained for long. By 1939 the world was again at war. Two years later, the US which had emerged from WWI as a major economic and military power, would for the second time in less than twenty-five years send its young men to fight and die on foreign battlefields. But this time, the stakes seemed so much higher.